Burkas and Bikinis: Playboy in Indonesia1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinema Recognizing Making Intimacy Vincent Tajiri Even Hotter!

FEBRUARY 2020 SOUTH AFRICA THROW SEX & BACK CINEMA RECOGNIZING MAKING INTIMACY VINCENT TAJIRI EVEN HOTTER! WITHOUT Flaunt THE MASK CANDID WITH YOUR ORVILLE PECK SWAG STERLING K. BROWN SHOWS US THE HOW SCOOP ON SEX! OUR SEXPERT SHARES INTIMATE DETAILS Dee Cobb WWW.PLAYBOY.CO.ZA R45.00 20019 9 772517 959409 EVERY. ISSUE. EVER. The complete Playboy archive Instant access to every issue, article, story, and pictorial Playboy has ever published – only on iPlayboy.com. VISIT PLAYBOY.COM/ARCHIVE SOUTH AFRICA Editor-in-Chief Dirk Steenekamp Associate Editor Jason Fleetwood Graphic Designer Koketso Moganetsi Fashion Editor Lexie Robb Grooming Editor Greg Forbes Gaming Editor Andre Coetzer Tech Editor Peter Wolff Illustrations Toon53 Productions Motoring Editor John Page Senior Photo Editor Luba V Nel ADVERTISING SALES [email protected] for more information PHONE: +27 10 006 0051 MAIL: PO Box 71450, Bryanston, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2021 Ƶč%./0(++.ǫ(+'ć+1.35/""%!.'Čƫ*.++/0.!!0Ē+1.35/ǫ+1(!2. ČĂāĊā EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.playboy.co.za FACEBOOK: facebook.com/playboysouthafrica TWITTER: @PlayboyMagSA INSTAGRAM: playboymagsa PLAYBOY ENTERPRISES, INTERNATIONAL Hugh M. Hefner, FOUNDER U.S. PLAYBOY ǫ!* +$*Čƫ$%!"4!10%2!þ!. ƫ++,!.!"*!.Čƫ$%!"ƫ.!0%2!þ!. Michael Phillips, SVP, Digital Products James Rickman, Executive Editor PLAYBOY INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHING !!*0!(Čƫ$%!"ƫ+))!.%(þ!.Ē! +",!.0%+*/ Hazel Thomson, Senior Director, International Licensing PLAYBOY South Africa is published by DHS Media House in South Africa for South Africa. Material in this publication, including text and images, is protected by copyright. It may not be copied, reproduced, republished, posted, broadcast, or transmitted in any way without written consent of DHS Media House. -

The Agency and Hilton & Hyland List Playboy Mansion for $200 Million

prnewswire.com http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-agency-and-hilton--hyland-list-playboy-mansion-for-200-million-300201987.html The Agency And Hilton & Hyland List Playboy Mansion For $200 Million One of America's Most Famous Addresses, Known for Legendary Parties and Lavish Lifestyle Hits the Market Playboy Enterprises, Inc. BEVERLY HILLS, Calif., Jan. 11, 2016 /PRNewswire/ -- The Agency and Hilton & Hyland announced today the listing of the Playboy Mansion for $200 million. The principal agents are Drew Fenton and Gary Gold of Hilton & Hyland and Mauricio Umansky of The Agency. "This is the right time to seek a buyer for this incredible property who understands the role the Mansion has played for our brand and enables us to continue to reinvest in the transformation of our business," said Playboy Enterprises CEO, Scott Flanders. "The Playboy Mansion has been a creative center for Hef as his residence and workplace for the past 40 years, as it will continue to be if the property is sold." The crown jewel of L.A.'s "Platinum Triangle" situated on 5 picturesque acres in Holmby Hills, The Playboy Mansion is a nearly 20,000 square foot residence that is both an ultra-private retreat and the ultimate setting for large-scale entertaining. The Mansion features 29 rooms and every amenity imaginable, including a catering kitchen, wine cellar, home theater, separate game house, gym, tennis court and freeform swimming pool with a large, cave-like grotto. The property also features a four-bedroom guest house. In addition, the Playboy Mansion is one of a select few private residences in L.A. -

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

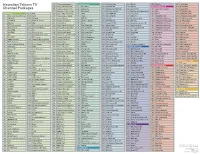

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

Stephen Hawking,These Are the Women in Scien

The Queen’s commonwealth Day Message 2021 The Queen’s commonwealth Day Message 2021: Over the coming week, as we celebrate the friendship, spirit of unity and achievements of the Commonwealth, we have an opportunity to reflect on a time like no other. Whilst experiences of the last year have been different across the Commonwealth, stirring examples of courage, commitment and selfless dedication to duty have been demonstrated in every Commonwealth nation and territory, notably by those working on the front line who have been delivering health care and other public services in their communities. We have also taken encouragement from remarkable advances in developing new vaccines and treatments. The testing times experienced by so many have led to a deeper appreciation of the mutual support and spiritual sustenance we enjoy by being connected to others. The need to maintain greater physical distance, or to live and work largely in isolation, has, for many people across the Commonwealth, been an unusual experience. In our everyday lives, we have had to become more accustomed to connecting and communicating via innovative technology – which has been new to some of us – with conversations and communal gatherings, including Commonwealth meetings, conducted online, enabling people to stay in touch with friends, family, colleagues, and counterparts who they have not been able to meet in person. Increasingly, we have found ourselves able to enjoy such communication, as it offers an immediacy that transcends boundaries or division, helping any sense of distance to disappear. We have all continued to appreciate the support, breadth of experiences and knowledge that working together brings, and I hope we shall maintain this renewed sense of closeness and community. -

Initial Interest Confusion

INITIAL INTEREST CONFUSION Excerpted from Chapter 7 (Rights in Internet Domain Names) of E-Commerce and Internet Law: A Legal Treatise With Forms, Second Edition, a 4-volume legal treatise by Ian C. Ballon (Thomson/West Publishing 2014) LAIPLA SPRING SEMINAR OJAI VALLEY INN OJAI, CA JUNE 6-8, 2014 Ian C. Ballon Greenberg Traurig, LLP Los Angeles: Silicon Valley: 1840 Century Park East, Ste. 1900 1900 University Avenue, 5th Fl. Los Angeles, CA 90067 East Palo Alto, CA 914303 Direct Dial: (310) 586-6575 Direct Dial: (650) 289-7881 Direct Fax: (310) 586-0575 Direct Fax: (650) 462-7881 [email protected] <www.ianballon.net> Google+, LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook: IanBallon This paper has been excerpted from E-Commerce and Internet Law: Treatise with Forms 2d Edition (Thomson West 2014 Annual Update), a 4-volume legal treatise by Ian C. Ballon, published by West LegalWorks Publishing, 395 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014, (212) 337-8443, www.ianballon.net. Ian C. Ballon Los Angeles 1840 Century Park East Shareholder Los Angeles, CA 90067 Internet, Intellectual Property & Technology Litigation T 310.586.6575 F 310.586.0575 Admitted: California, District of Columbia and Maryland Silicon Valley JD, LLM, CIPP 1900 University Avenue 5th Floor [email protected] East Palo Alto, CA 94303 Google+, LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook: Ian Ballon T 650.289.7881 F 650.462.7881 Ian Ballon represents Internet, technology, and entertainment companies in copyright, intellectual property and Internet litigation, including the defense of privacy and behavioral advertising class action suits. He is also the author of the leading treatise on Internet law, E-Commerce and Internet Law: Treatise with Forms 2d edition, the 4-volume set published by West (www.IanBallon.net). -

Xfinity Channel Lineup

Channel Lineup 1-800-XFINITY | xfinity.com SARASOTA, MANATEE, VENICE, VENICE SOUTH, AND NORTH PORT Legend Effective: April 1, 2016 LIMITED BASIC 26 A&E 172 UP 183 QUBO 738 SPORTSMAN CHANNEL 1 includes Music Choice 27 HLN 179 GSN 239 JLTV 739 NHL NETWORK 2 ION (WXPX) 29 ESPN 244 INSP 242 TBN 741 NFL REDZONE <2> 3 PBS (WEDU SARASOTA & VENICE) 30 ESPN2 42 BLOOMBERG 245 PIVOT 742 BTN 208 LIVE WELL (WSNN) 31 THE WEATHER CHANNEL 719 HALLMARK MOVIES & MYSTERIES 246 BABYFIRST TV AMERICAS 744 ESPNU 5 HALLMARK CHANNEL 32 CNN 728 FXX (ENGLISH) 746 MAV TV 6 SUNCOAST NEWS (WSNN) 33 MTV 745 SEC NETWORK 247 THE WORD NETWORK 747 WFN 7 ABC (WWSB) 34 USA 768-769 SEC NETWORK (OVERFLOW) 248 DAYSTAR 762 CSN - CHICAGO 8 NBC (WFLA) 35 BET 249 JUCE 764 PAC 12 9 THE CW (WTOG) 36 LIFETIME DIGITAL PREFERRED 250 SMILE OF A CHILD 765 CSN - NEW ENGLAND 10 CBS (WTSP) 37 FOOD NETWORK 1 includes Digital Starter 255 OVATION 766 ESPN GOAL LINE <14> 11 MY NETWORK TV (WTTA) 38 FOX SPORTS SUN 57 SPIKE 257 RLTV 785 SNY 12 IND (WMOR) 39 CNBC 95 POP 261 FAMILYNET 47, 146 CMT 13 FOX (WTVT) 40 DISCOVERY CHANNEL 101 WEATHERSCAN 271 NASA TV 14 QVC 41 HGTV 102, 722 ESPNEWS 279 MLB NETWORK MUSIC CHOICE <3> 15 UNIVISION (WVEA) 44 ANIMAL PLANET 108 NAT GEO WILD 281 FX MOVIE CHANNEL 801-850 MUSIC CHOICE 17 PBS (WEDU VENICE SOUTH) 45 TLC 110 SCIENCE 613 GALAVISION 17 ABC (WFTS SARASOTA) 46 E! 112 AMERICAN HEROES 636 NBC UNIVERSO ON DEMAND TUNE-INS 18 C-SPAN 48 FOX SPORTS ONE 113 DESTINATION AMERICA 667 UNIVISION DEPORTES <5> 19 LOCAL GOVT (SARASOTA VENICE & 49 GOLF CHANNEL 121 DIY NETWORK 721 TV GAMES 1 includes Limited Basic VENICE SOUTH) 50 VH1 122 COOKING CHANNEL 734 NBA TV 1, 199 ON DEMAND (MAIN MENU) 19 LOCAL EDUCATION (MANATEE) 51 FX 127 SMITHSONIAN CHANNEL 735 CBS SPORTS NETWORK 194 MOVIES ON DEMAND 20 LOCAL GOVT (MANATEE) 55 FREEFORM 129 NICKTOONS 738 SPORTSMAN CHANNEL 299 FREE MOVIES ON DEMAND 20 LOCAL EDUCATION (SARASOTA, 56 AMC 130 DISCOVERY FAMILY CHANNEL 739 NHL NETWORK 300 HBO ON DEMAND VENICE & VENICE SOUTH) 58 OWN 131 NICK JR. -

Residential Rates

RESIDENTIAL RATES Broadband Internet Services Service Download Upload Data Plan Monthly FreeNet 2 Mbps 1 Mbps Unlimited $0.00 Starter 25 Mbps 3 Mbps 250 GB $39.99 Essential 100 Mbps 5 Mbps 250 GB $69.99 Ultimate 200 Mbps 5 Mbps 250 GB $89.99 Supreme 400 Mbps 10 Mbps Unlimited $139.99 Gig Plus 1000 Mbps 10 Mbps Unlimited $199.99 Internet Service Add-Ons Internet Equipment Fee (Modem Rental) $10.00 Static IP Address $20.00 150 GB of Data (Pre-Purchased) $15.00 Unlimited Data $30.00 Double Upload $20.00 In-House Amplifier $42.00 Brainiac Services HD Cable TV Services Brainiac Services Local 30+ (Including Broadcast $24.99 Brainiacs $10.00 Retransmission Fee of $15.00) SmartNet $11.99 Popular Standard $113.97 SmartNet Plus $19.99 StreamTV Bitdefender $2.99 StreamTV (Requires Local 30+) $5.00 SmartNet Beacon $5.00 50 Additional Hours $5.00 Brainiac Equipment Options Add 1 Stream $5.00 SmartNet Beacon $149.00 StreamTV Box $6.00 Hitron WiFi Extender $49.99 StreamTV Ultra $12.00 Hitron Data Gateway $99.99 Pak Add-Ons (StreamTV or Converter Required) Hitron Voice Gateway $129.99 Digital Plus Pak $4.25 Brainiac Support Services Alma Latina Pak $4.95 HD Plus Pak $8.75 In-Home Support (Non- $90.00 Brainiac Subscriber/Per Hour) Digital Basic Pak $17.00 In-Home Support $45.00 (Brainiac Subscriber/Per Hour) Cable TV Equipment Options Remote PC Optimization (One-Time Fee) $75.00 Guide Navigator Service $1.50 Virus, Adware, Malware HD DTA $1.95 $75.00 Removal (One-Time Fee) Cable Card $3.35 Brainiacs and Bitdefender require a 12-month Digital Converter $6.95 commitment. -

Media Entity Fox News Channel Oct

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Programming Service Launch Ownership by Date "Other" Media Entity Fox News Channel Oct. 96 NewsCoqJ. Fox Reality May 05 News Corp. Fox Sports Net Nov. 97 News Corp. Fox Soccer Channel (fonnerly Fox Sports World) Nov. 97 News Corp. FX Jun. 94 News Corp. Fuel .luI. 03 News Corp. Frec Speech TV (FSTV) Jun. 95 Game Show Network (GSN) Dec. 94 Liberty Media Golden Eagle Broadcasting Nov. 98 preat American Country Dec. 95 EW Scripps Good Samaritan Network 2000 Guardian Television Network 1976 Hallmark Channel Sep.98 Liberty Media Hallmark Movie Channel Jan. 04 HDNET Sep.OI HDNET Movies Jan. 03 Healthy Living Channel Jan. 04 Here! TV Oct. 04 History Channel Jan. 95 Disney, NBC-Universal, Hearst History International Nov. 98 Disney, NBC-Universal, Hearst (also called History Channel International) Home & Garden Television (HGTV) Dec. 94 EW Scripps Home Shopping Network (HSN) Jul. 85 Home Preview Channel Horse Racing TV Dec. 02 !Hot Net (also called The Hot Network) Mar. 99 Hot Net Plus 2001 Hot Zone Mar. 99 Hustler TV Apr. 04 i-Independent Television (fonnerly PaxTV) Aug. 98 NBC-Universal, Paxson ImaginAsian TV Aug. 04 Inspirational Life Television (I-LIFETV) Jun. 98 Inspirational Network (INSP) Apr. 90 i Shop TV Feb. 01 JCTV Nov. 02 Trinity Broadcasting Network 126 Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Programming Service Launch Ownership by Date "Other" Media EntIty ~ewelry Television Oct. 93 KTV ~ Kids and Teens Television Dominion Video Satellite Liberty Channel Sep. 01 Lifetime Movie Network .luI. 98 Disney, Hearst Lifetime Real Women Aug. -

SPECTRUM HD CHANNEL LINEUP° Desert Cities | July 2017

SPECTRUM HD CHANNEL LINEUP° Desert Cities | July 2017 TV PACKAGES 31 FOX Deportes 312 NHL Network 933 HITN 66 Travel Channel 371 ESPN GoalLn/Buzz.Bt 935 Mexicanal SPECTRUM BASIC 70 TCM 372 FCS Atlantic 936 El Garage TV 73 Golf Channel 373 FCS Central 937 Ultra Macho (Includes Digital Music channels 75 LMN 374 FCS Pacific 945 EWTN en Español and the following services) 85 CMT 376 PAC-12 Los Angeles 946 TBN Enlace USA 2 KESQ - CBS 86 Disney XD 377 PAC-12 Arizona 962 AyM Sports 3 KESQ - ABC 87 Disney Junior 378 PAC-12 Washington 971 Cinelatino 4 KNBC - NBC 93 FXX 379 PAC-12 Oregon 972 Cine Mexicano 5 KCWQ - The CW 119 MTV2 380 PAC-12 Mountain 979 De Película Clásico 7 KABC - ABC 120 MTV Classic 381 PAC-12 Bay Area 980 De Película 8 PBS SoCal 124 UP 382 BTN 982 ViendoMovies 9 KVCR - PBS 128 Reelz 388 BTN - Extra1 983 Ultra Mex 10 C-SPAN 130 Nat Geo Wild 389 BTN - Extra2 984 Ultra Cine 11 KDFX - FOX 131 Smithsonian Channel 408 Outdoor Channel 985 Ultra Clásico 12 KVER - Univisión 133 Viceland 413 TVG 13 KMIR - NBC 134 fyi, 417 BeIN SPORTS MI PLAN LATINO 14 KMIR - MeTV 145 El Rey Network 419 FOX Soccer Plus 15 KUNA - Telemundo 161 DIY Network 420-424 Sports Overflow (Includes Spectrum TV Basic, Latino 16 KCAL - IND 163 Cooking Channel 443 BeIN SPORTS Español View and the following services) 17 Government Access 169 Fuse 468 The Cowboy Channel 36 TNT 20 KPSE - MyTV 174 Lifetime Real Women 469 Jewish Life TV 37 USA Network 25 KEVC - UniMás 179 LOGO 620 MoviePlex 38 TBS 27 Government Access 180 Discovery Life Channel 621 IndiePlex 39 A&E 84 Charter Public Community 182 Centric 622 RetroPlex 40 Discovery Channel Access 184 TV One 623 FLIX - E 41 TLC 98 Community Bulletin Board 185 ASPiRE TV 634 NBC Universal 42 HISTORY 99 C-SPAN2 187 Ovation 640 HDNet Movies 43 Bravo 159 QVC 209 BBC World News 1554 Willow Plus Cricket 44 HGTV 255 Sprout 45 Food Network 176 HSN TMC 188 Jewelry TV 256 Baby First TV 47 AMC 194 EVINE 257 Nick Jr. -

Authority in , and Support

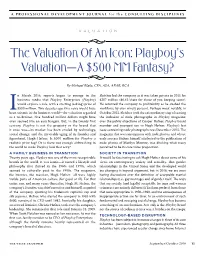

The Profession's Leading Authority in A PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT JOURNAL for the CONSULTING DISCIPLINES Valuation Data, Research, and Support VALUATION • Through its five web-based annual subscription packages, KeyValueData® offers Internet-based access to thousands of BUNDLES dollars in essential valuation data, research, and tools—all TITANIUM The Valuation Of An Icon: Playboy’s PLATINUM for a single, low annual subscription fee.* SILVER GOLD ECON Valuation—A $500 MM Fantasy? Purchase a Database à la Carte À LA CARTE ASSIST SAVE SAVE SAVE SAVE or Bundle and Save PRICE 46% 44% 40% 49% • IBA Market Data (Downloads Per Year) 7 $495 Unlimited Unlimited Unlimited By Michael Blake, CFA, ASA, ABAR, BCA BIZCOMPS® (Downloads Per Year) $540 3 7 10 10 Guideline Public Company Database (Downloads Per Year) $495 7 10 Unlimited Unlimited n March 2016, reports began to emerge in the Fletcher led the company as it was taken private in 2011 for IRS Corporate Ratios Database $275 business media that Playboy Enterprises (Playboy) $207 million ($6.15/share for those of you keeping score). RMA Valuation Edition (Includes 10 years of RMA data) $925 would explore a sale, with a starting (asking) price of He returned the company to profitability as he slashed the Duff & Phelps Valuation Handbook + Decile Data + $669 $500 million. Two decades ago, this news would have workforce by over ninety percent. Perhaps most notably, in Cost Of Capital Analyzer been seismic in the business world—the valuation regarded October 2015, Fletcher took the extraordinary step of ceasing Pluris DLOM DatabaseTM $595 asI a no-brainer. -

Hawaiian Telcom TV Channel Packages

Hawaiian Telcom TV 604 Stingray Everything 80’s ADVANTAGE PLUS 1003 FOX-KHON HD 1208 BET HD 1712 Pets.TV 525 Thriller Max 605 Stingray Nothin but 90’s 21 NHK World 1004 ABC-KITV HD 1209 VH1 HD MOVIE VARIETY PACK 526 Movie MAX Channel Packages 606 Stingray Jukebox Oldies 22 Arirang TV 1005 KFVE (Independent) HD 1226 Lifetime HD 380 Sony Movie Channel 527 Latino MAX 607 Stingray Groove (Disco & Funk) 23 KBS World 1006 KBFD (Korean) HD 1227 Lifetime Movie Network HD 381 EPIX 1401 STARZ (East) HD ADVANTAGE 125 TNT 608 Stingray Maximum Party 24 TVK1 1007 CBS-KGMB HD 1229 Oxygen HD 382 EPIX 2 1402 STARZ (West) HD 1 Video On Demand Previews 126 truTV 609 Stingray Dance Clubbin’ 25 TVK2 1008 NBC-KHNL HD 1230 WE tv HD 387 STARZ ENCORE 1405 STARZ Kids & Family HD 2 CW-KHON 127 TV Land 610 Stingray The Spa 28 NTD TV 1009 QVC HD 1231 Food Network HD 388 STARZ ENCORE Black 1407 STARZ Comedy HD 3 FOX-KHON 128 Hallmark Channel 611 Stingray Classic Rock 29 MYX TV (Filipino) 1011 PBS-KHET HD 1232 HGTV HD 389 STARZ ENCORE Suspense 1409 STARZ Edge HD 4 ABC-KITV 129 A&E 612 Stingray Rock 30 Mnet 1017 Jewelry TV HD 1233 Destination America HD 390 STARZ ENCORE Family 1451 Showtime HD 5 KFVE (Independent) 130 National Geographic Channel 613 Stingray Alt Rock Classics 31 PAC-12 National 1027 KPXO ION HD 1234 DIY Network HD 391 STARZ ENCORE Action 1452 Showtime East HD 6 KBFD (Korean) 131 Discovery Channel 614 Stingray Rock Alternative 32 PAC-12 Arizona 1069 TWC SportsNet HD 1235 Cooking Channel HD 392 STARZ ENCORE Classic 1453 Showtime - SHO2 HD 7 CBS-KGMB 132 -

18. Jahresbericht 2015/2016

18. Jahresbericht 2015/2016 Berichtszeitraum 01.07.2015 bis 30.06.2016 15 16 Impressum Herausgeber die medienanstalten – ALM GbR Friedrichstraße 60 10117 Berlin Tel: +49 30 206 46 90 0 Fax: +49 30 206 46 90 99 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.kek-online.de www.die-medienanstalten.de Verantwortlich Prof. Dr. Ralf Müller-Terpitz Redaktion Constanze Barz Kerstin Kopf Bernd Malzanini Michael Petri Lektorat VISTAS Verlag, Leipzig Copyright © 2016 by die medienanstalten – ALM GbR Gestaltung Rosendahl Berlin Satz VISTAS Verlag, Leipzig Druck trigger.medien.gmbh, Berlin Stand: Juni 2016 18. Jahresbericht der KEK herausgegeben von die medienanstalten – ALM GbR 4 Inhalt 1 Überblick 9 2 Medienkonzentrationskontrolle durch die KEK 13 2.1 Verfassungsrechtliche Grundlage 13 2.2 Aufgaben der KEK nach dem Rundfunkstaatsvertrag 14 2.3 Mitglieder der KEK 15 2.4 Organisation 16 3 Verfahren im Berichtszeitraum 19 3.1 Zulassung von Fernsehveranstaltern 19 3.1.1 ClipMyHorse.TV Deutschland GmbH – „ClipMyHorse.TV“ (Az.: KEK 834) 19 3.1.2 Rocket Beans Entertainment GmbH – „rocketbeans.tv“ (Az.: KEK 836) 20 3.1.3 Classica GmbH – „CLASSICA“ (Az.: KEK 835) 21 3.1.4 Studio 100 Media GmbH – „Junior“ (Az.: KEK 841) 22 3.1.5 DAF Deutsches Anleger Fernsehen AG – „DAF“ (Az.: KEK 842) 23 3.1.6 RTV Broadcast & Content Management GmbH – „Nasch Kinomir“, „Telebom/Teledom“ (Az.: KEK 845) 24 3.1.7 MUXX.tv GmbH – „MUXX.tv“ (Az.: KEK 849) 25 3.1.8 L.SU.TV Ltd. Niederlassung Deutschland – „Latizón TV“ (Az.: KEK 850) 25 3.1.9 Sky Deutschland Fernsehen GmbH & Co.