Secondary Labour Force Or Permanent Staff?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communal Commercial Check City of Aachen

Eigentum von Fahrländer Partner AG, Zürich Communal commercial check City of Aachen Location Commune Aachen (Code: 5334002) Location Aachen (PLZ: 52062) (FPRE: DE-05-000334) Commune type City District Städteregion Aachen District type District Federal state North Rhine-Westphalia Topics 1 Labour market 9 Accessibility and infrastructure 2 Key figures: Economy 10 Perspectives 2030 3 Branch structure and structural change 4 Key branches 5 Branch division comparison 6 Population 7 Taxes, income and purchasing power 8 Market rents and price levels Fahrländer Partner AG Communal commercial check: City of Aachen 3rd quarter 2021 Raumentwicklung Eigentum von Fahrländer Partner AG, Zürich Summary Macro location text commerce City of Aachen Aachen (PLZ: 52062) lies in the City of Aachen in the District Städteregion Aachen in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Aachen has a population of 248'960 inhabitants (31.12.2019), living in 142'724 households. Thus, the average number of persons per household is 1.74. The yearly average net migration between 2014 and 2019 for Städteregion Aachen is 1'364 persons. In comparison to national numbers, average migration tendencies can be observed in Aachen within this time span. According to Fahrländer Partner (FPRE), in 2018 approximately 34.3% of the resident households on municipality level belong to the upper social class (Germany: 31.5%), 33.6% of the households belong to the middle class (Germany: 35.3%) and 32.0% to the lower social class (Germany: 33.2%). The yearly purchasing power per inhabitant in 2020 and on the communal level amounts to 22'591 EUR, at the federal state level North Rhine-Westphalia to 23'445 EUR and on national level to 23'766 EUR. -

Die Euregiobahn

Stolberg-Mühlener Bahnhof – Stolberg-Altstadt 2021 > Fahrplan Stolberg Hbf – Eschweiler-St. Jöris – Alsdorf – Herzogenrath – Aachen – Stolberg Hbf Eschweiler-Talbahnhof – Langerwehe – Düren Bahnhof/Haltepunkt Montag – Freitag Mo – Do Fr/Sa Stolberg Hbf ab 5:11 6:12 7:12 8:12 18:12 19:12 20:12 21:12 22:12 23:12 23:12 usw. x Eschweiler-St. Jöris ab 5:18 6:19 7:19 8:19 18:19 19:19 20:19 21:19 22:19 23:19 23:19 alle Alsdorf-Poststraße ab 5:20 6:21 7:21 8:21 18:21 19:21 20:21 21:21 22:21 23:21 23:21 60 Alsdorf-Mariadorf ab 5:22 6:23 7:23 8:23 18:23 19:23 20:23 21:23 22:23 23:23 23:23 Minu- x Alsdorf-Kellersberg ab 5:24 6:25 7:25 8:25 18:25 19:25 20:25 21:25 22:25 23:25 23:25 ten Alsdorf-Annapark an 5:26 6:27 7:27 8:27 18:27 19:27 20:27 21:27 22:27 23:27 23:27 Alsdorf-Annapark ab 5:31 6:02 6:32 7:02 7:32 8:02 8:32 9:02 18:32 19:02 19:32 20:02 20:32 21:02 21:32 22:02 22:32 23:32 23:32 Alsdorf-Busch ab 5:33 6:04 6:34 7:04 7:34 8:04 8:34 9:04 18:34 19:04 19:34 20:04 20:34 21:04 21:34 22:04 22:34 23:34 23:34 Herzogenrath-A.-Schm.-Platz ab 5:35 6:06 6:36 7:06 7:36 8:06 8:36 9:06 18:36 19:06 19:36 20:06 20:36 21:06 21:36 22:06 22:36 23:36 23:36 Herzogenrath-Alt-Merkstein ab 5:38 6:09 6:39 7:09 7:39 8:09 8:39 9:09 18:39 19:09 19:39 20:09 20:39 21:09 21:39 22:09 22:39 23:39 23:39 Herzogenrath ab 5:44 6:14 6:44 7:14 7:44 8:14 8:44 9:14 18:44 19:14 19:44 20:14 20:45 21:14 21:44 22:14 22:44 23:43 23:43 Kohlscheid ab 5:49 6:19 6:49 7:19 7:49 8:19 8:49 9:19 18:49 19:19 19:49 20:19 20:50 21:19 21:49 22:19 22:49 23:49 23:49 Aachen West ab 5:55 6:25 6:55 -

Germany As a “Melting Pot”? Conceptions of Otherness Over Time

Germany as a “Melting Pot”? Conceptions of Otherness Over Time By Emma Gutman Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology Senior Honors Thesis Brandeis University May 2018 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Chapter 1: Introduction 5 Chapter 2: Otherness Throughout German History 20 Chapter 3: Being German and (Legally) Becoming German 36 Chapter 4: Getting to Know You: German Attitudes Towards and Experience With Minority Groups 56 Chapter 5: Schaffen Wir Das?: Global Governance in the Refugee Crisis and National, Local, or Individual Responsibility for Integration 80 Chapter 6: Jews and Muslims: Applying the Lessons of the Past to the Present through Holocaust Education 98 Chapter 7: Conclusion 113 Works Cited 120 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Sarah Lamb, for her enthusiastic support and guidance from the moment I approached her about this topic, way over a year ago and shortly before I was about to leave for abroad. Professor Lamb was invaluable in helping me figure out all the necessary paperwork and procedures for conducting interviews, even when we could not meet in person. When I returned and began working on the paper itself, she was a source of validation for my writing skills and of constructive criticism that pushed me to think more critically and theoretically about the subject matter than ever before, only strengthening the final product. I would also like to thank the entire Anthropology Department at Brandeis University for introducing me, originally just a History major, to this wonderful discipline. I have had some of the most eye-opening educational moments of my undergraduate career during Anthropology class discussions. -

Bezeichnung Adresse Nr PLZ Ort Öffnungszeiten Öffentliche

Bezeichnung Adresse Nr PLZ Ort Öffnungszeiten Öffentliche Telefonnummer Acnos Apotheke im Aquis Plaza Adalbertstraße 100 52062 Aachen Mo -Fr 9-17, Sa 10-18 0241/34771 Habsburger Apotheke Hohenstaufenallee 19 52062 Aachen Mo -Fr 09:00-18:00, Sa 9:15-13:00 0241/76746 Malteser Apotheke Malteserstraße 20 52062 Aachen Mo-Fr 9-13 und 14-18, Sa 10-15 0241/31074 SF-Testzentrum Aachen Markt, Villa Kunterbunt Aachen Markt 1-3 52062 Aachen Mo-Fr 7:30-19:30, Sa 8-18 Rapid Care Theaterplatz Theaterplatz 1 52062 Aachen Mo-Fr 8-20, Sa 9-18, So 9-15 Dr. med. Anita Harst Großkölnstraße 22-28 52062 Aachen 0241/9291400 Dr. med. Scheima Rahmaty-Taheri Alexanderstraße 11-15 52062 Aachen 0241/55910590 Dr. med. Scheima Rahmaty-Taheri Alexanderstraße 11-15 52062 Aachen Dr. med. Doris Niederau Alexanderstraße 11-15 52062 Aachen Karolinger Apotheke Karlsgraben 8 52064 Aachen Mo-Sa 8:30-18:30 0241/402626 SF-Testzentrum AC HBF Bahnhofplatz 52064 Aachen Mo-fr 7-20, Sa 7:30-18, So 8-18 Dr. med. Ulrike Schulte-Stracke Krakaustraße 27a 52064 Aachen Apotheke am Marienhospital Viehhofstr. 43 52066 Aachen Mo-Fr 8-17, Sa 8.30-13 Via Life Schwertbad Burtscheider Markt 22 52066 Aachen Mo-Fr 8-18, Sa 9-14 RapidCare Rothe Erde Beverstraße 27 52066 Aachen Mo-Fr 7-11 und 14-18, Sa 9-14 Sanitätshaus Koczyba, Aachener Tierpark Obere Drimbornstraße 44 52066 Aachen Mo.-Fr.: 08:00 - 12:00 Uhr / 15:00 - 19:00 Uhr; Sa.-So.: 09:00 - 17:00 0800 797 0 797 Vialife Bardenberg GmbH Rosenquelle Kurbrunnenstraße 5 52066 Aachen Mo-Fr 7-11 und 15-18, Sa 8-11 Hausärztliche Praxis Dr. -

Bus Linie 51V Fahrpläne & Karten

Bus Linie 51V Fahrpläne & Netzkarten 51V Baesweiler, Setterich Siedlung - Aachen, Im Website-Modus Anzeigen Bushof Die Bus Linie 51V (Baesweiler, Setterich Siedlung - Aachen, Bushof) hat 5 Routen (1) Aachen Bushof: 07:15 (2) Alter Tivoli: 07:36 (3) Baesweiler Reyplatz: 13:35 (4) Elisenbrunnen: 13:18 (5) Setterich Siedlung: 15:35 Verwende Moovit, um die nächste Station der Bus Linie 51V zu ƒnden und, um zu erfahren wann die nächste Bus Linie 51V kommt. Richtung: Aachen Bushof Bus Linie 51V Fahrpläne 39 Haltestellen Abfahrzeiten in Richtung Aachen Bushof LINIENPLAN ANZEIGEN Montag 07:15 Dienstag 07:15 Baesweiler, Setterich Siedlung Siebenbürgenstraße 11, Baesweiler Mittwoch 07:15 Baesweiler, Setterich Neue Mitte Donnerstag 07:15 Hauptstraße 100, Baesweiler Freitag 07:15 Baesweiler, Setterich Bahnstraße Samstag Kein Betrieb Hauptstraße 40, Baesweiler Sonntag Kein Betrieb Baesweiler, Setterich Im Weinkeller Hauptstraße 3, Baesweiler Baesweiler, Place De Montesson Auguste-Renoir-Straße, Baesweiler Bus Linie 51V Info Richtung: Aachen Bushof Baesweiler, Jülicher Straße Stationen: 39 Jülicher Straße, Baesweiler Fahrtdauer: 61 Min Linien Informationen: Baesweiler, Setterich Siedlung, Baesweiler, Parkstraße Baesweiler, Setterich Neue Mitte, Baesweiler, Aachener Straße 177, Baesweiler Setterich Bahnstraße, Baesweiler, Setterich Im Weinkeller, Baesweiler, Place De Montesson, Baesweiler, In Der Schaf Baesweiler, Jülicher Straße, Baesweiler, Parkstraße, In Der Schaf 10, Baesweiler Baesweiler, In Der Schaf, Baesweiler, Rathaus, Baesweiler, Oidtweiler -

Amtliches Mitteilungsblatt Für Bürgerinnen Und Bürger Der Stadt Alsdorf

Amtliches Mitteilungsblatt für Bürgerinnen und Bürger der Stadt Alsdorf Jahrgang Alsdorf, Nummer: Verleger und Herausgeber: Stadt Alsdorf Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, A 13 ‐ Amt für Kultur und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Postanschrift: das Amtsblatt – Amtliche Mitteilungsblatt der Stadt Alsdorf ist das gesetzlich Hubertusstraße 17 52477 Alsdorf vorgeschriebene Bekanntmachungsorgan der Stadt. Telefon: 0 24 04 / 50 ‐ 294 FAX: 0 24 04 / 50 ‐ 303 Homepage: www.alsdorf. .de Das Amtsblatt wird im Internet kostenfrei veröffentlicht auf der Homepage E‐Mail: der Stadt Alsdorf unter www.alsdorf.de. [email protected] Verantwortlich: Der Bürgermeister Mit freundlichen Grüßen Veröffentlichung: . Aushang im Rathausfoyer . Mitnahme im Rathausfoyer Alfred Sonders . im Internet abrufbar unter www.alsdorf.de (im Bereich Bürgermeister “Aktuelles”) ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN Allgemeine Besuchszeiten: Mo. ‐ Fr. 8.30 ‐ 12.00 Uhr Mi. 14.00 ‐ 18.00 Uhr und nach Vereinbarung Besuchszeiten Meldeamt: Mo./Di./Do. 7.30 - 16.00 Uhr Mi. 7.30 - 18.00 Uhr Fr. 7.30 - 12.00 Uhr Besuchszeiten Sozialamt: Mo./Di./Do./Fr. 8.30 - 12.00 Uhr Mi. 14.00 - 18.00 Uhr ansonsten ausschließlich nach telefonischer Vereinbarung Besuchszeiten Asylstelle: Di./Fr. 8.30 - 12.00 Uhr Mi. 14.00 - 18.00 Uhr ansonsten ausschließlich nach telefonischer Vereinbarung Amtliches Mitteilungsblatt der Stadt Alsdorf / Amtsblatt / 29. Juli 2020 / Nr. 31 / Seite 200 Stadt Alsdorf Der Erste Beigeordnete als Wahlleiter BEKANNTMACHUNG Zugelassene Wahlvorschläge für die Wahlen des Bürgermeisters/der Bürgermeisterin sowie der Vertretung der Stadt Alsdorf am 13. September 2020 Nach §§ 19, 46 b des Kommunalwahlgesetzes (KWahlG) in Verbindung mit §§ 75 b Absatz 7, 30, 31 Absatz 4 der Kommunalwahlordnung (KWahlO) gebe ich hiermit bekannt, dass der Wahlausschuss in seiner Sitzung am 28.07.2020 folgende Wahlvorschläge für die Wahl des Bürgermeisters/der Bürgermeisterin sowie der Vertretung der Stadt Alsdorf zugelassen hat: A. -

Filialen Mit Sonderöffnungszeiten (Stand: September 2018)

S Filialen mit Sonderöffnungszeiten (Stand: September 2018) Aachen Filiale Uniklinik Montag und Donnerstag 09.30 – 16.15 Uhr Dienstag und Mittwoch 09.30 – 18.00 Uhr Freitag 09.30 – 13.00 Uhr Filiale Campus Montag bis Donnerstag 10.00 – 15.00 Uhr Freitag 10.00 – 13.00 Uhr Filiale Ahornstraße Service Montag bis Freitag 09.30 – 13.00 Uhr Donnerstag zusätzlich 16.00 – 18.00 Uhr Beratung nach Vereinbarung Montag bis Freitag 09.30 – 13.00 Uhr Montag bis Donnerstag 14.00 – 18.00 Uhr Filiale Valkenburger Straße Service Montag bis Freitag 09.30 – 13.00 Uhr Donnerstag zusätzlich 16.00 – 18.00 Uhr Beratung nach Vereinbarung Montag bis Freitag 09.30 – 13.00 Uhr Montag bis Donnerstag 14.00 – 18.00 Uhr Alsdorf Filiale Alsdorf-Ofden Montag und Mittwoch 14.00 – 18.00 Uhr Dienstag und Donnerstag 09.30 – 12.15 Uhr S Eschweiler Filiale Wardenslinde Montag, Mittwoch, Freitag 09.30 – 13.00 Uhr Montag, Dienstag, Donnerstag 14.00 – 18.00 Uhr Herzogenrath Filiale Herzogenrath-Straß Montag und Mittwoch 09.30 – 12.15 Uhr Dienstag und Donnerstag 14.00 – 18.00 Uhr Freitag 09.30 – 13.00 Uhr Monschau Filiale Monschau-Höfen Service Montag bis Freitag 09.30 – 13.00 Uhr Donnerstag zusätzlich 16.00 – 18.00 Uhr Beratung nach Vereinbarung Montag bis Freitag 09.30 – 13.00 Uhr Montag bis Donnerstag 14.00 – 18.00 Uhr Filiale Monschau-Kalterherberg Service Montag bis Freitag 09.30 – 13.00 Uhr Donnerstag zusätzlich 16.00 – 18.00 Uhr Beratung nach Vereinbarung Montag bis Freitag 09.30 – 13.00 Uhr Montag bis Donnerstag 14.00 – 18.00 Uhr Filiale Monschau-Konzen Montag und Mittwoch -

Kinderschutzfachkräfte Gem. § 8 a SGB VIII in Der Städteregion Aachen

Kinderschutzfachkräfte gem. § 8 a SGB VIII in der StädteRegion Aachen Alsdorf Name Arbeitsbereich Telefon Michael Raida Jugendamt 02404 - 50 433 Sabine Weller Jugendamt 02404 - 50 340 Andre Pabich Jugendamt 02404 - 50 263 Peter Bohlmann Jugendamt 02404 - 50 260 Karin Rohrbeck Jugendamt 02404 - 50 321 Alexandra Löwenstein Jugendamt 02404 - 50 312 Sonja Kohl Jugendamt 02404 - 50 255 Simona Flocke Jugendamt 02404 - 50 418 Alexandra Hilger Jugendamt 02404 - 50 215 Celik Öztürk-Cuhadar Jugendamt 02404 - 50 287 Lara Birmanns Jugendamt 02404 - 50 385 Jochen Neukirch Jugendamt 02404 - 50 428 Claudia Möllering-Hess SKF Alsdorf 0177 - 77 932 22 Harald Becker SKF Alsdorf 02404 - 93 222 Renate Dittrich SKF Alsdorf 02404 - 93 222 Andreas Malecha SKF Alsdorf/ PP Aachen 0241 - 95 773 4480 Claudia Jansen Diakonie Alsdorf 02404 - 949511 Eschweiler Arbeitsbereich Telefon Name Stefan Pietsch Jugendamt 02403 - 71 287 Rolf Dahmen Jugendamt 02403 - 71 391 Silvia Frings Jugendamt 02403 - 71 485 Peter Harter Jugendamt 02403 - 71 272 Dietlind Höfeler Jugendamt 02403 - 71 278 Ludger Leister Jugendamt 02403 - 71 283 Mathilde Uhr Jugendamt 02403 - 71 469 Simone Bast Jugendamt 02403 - 71 501 Christiane Preuschoff Jugendamt 02403 - 71 610 Anja Schwerdtfeger Jugendamt 02403 - 71 273 Angelika Henn Jugendamt 02403 - 71 707 Janina Franken Jugendamt 02403 - 71 634 Markus Eßer Jugendamt 02403 - 71 444 Melanie Lehnhoff Jugendamt 02403 - 71 317 Sarag Gieß Jugendamt 02403 - 71 290 Gerrit Gobbelé Jugendamt 02403 - 71 229 Robert Wagner Haus St. Josef 02403 - 78 58 50 Ina Stein-Gerhards Haus St. Josef 02403 - 78 58 21 Christof Lippert Haus St. Josef 02403 - 78 58 40 Johanna Hansen Haus St. Josef 02403 - 78 58 27 Bogumilia Porwik-Hermanns Haus St. -

Bodenrichtwertliste 2020 Seite 1 Von 22

Bodenrichtwertliste 2020 interne BRW Nutzungs- Geschoss- Tiefe Zonen- Lagebezeichnung 2020 GFZ Breite art zahl [m] nummer [€/m²] Adalbertstraße zw. Friedrich-Wilhelm-Platz und 01263 Aachen Kugelbrunnen - Erschließung über die 8500,00 MK IV-V 30 Adalbertstraße 01112 Aachen Holzgraben und Bereich Glaskubus 6500,00 MK IV-V 30 01118 Aachen Krämerstraße 6000,00 MI III-IV 30 01206 Aachen Ursulinerstraße / Buchkremerstraße 5000,00 MI/MK IV-V 30 01291 Aachen Markt östlich 4600,00 MK IV-V 30 Friedrich-Wilhelm-Platz - inklusive Bereich der 01106 Aachen 4500,00 MK IV-V 30 Elisengalerie 01110 Aachen Hartmannstraße 4300,00 MI III-IV 30 01246 Aachen Fischmarkt und Schmiedstraße 3800,00 MI III-IV 30 01290 Aachen Markt westlich 3200,00 MI/MK III-IV 30 01272 Aachen Alter Posthof 3000,00 MI IV-V 30 01107 Aachen Großkölnstraße (Markt bis Kleinkölnstraße) 2900,00 MK IV-V 30 01266 Aachen Hof / Hühnermarkt / Büchel 2800,00 MI IV-V 30 Pontstraße zwischen Friesenstraße und 01004 Aachen 2300,00 MI IV-V 30 Templergraben 01125 Aachen Pontstraße (Markt bis Theresienkirche) 2200,00 MK III-IV 30 Peterstraße zwischen Büchel und Friedrich- 01123 Aachen 2000,00 MK IV-V 30 Wilhelm-Platz 01292 Aachen 1900,00 MK IV-V 30 Fußgängerzone Burtscheider Markt bis 01189 Aachen 1850,00 MI IV-V 30 Kapellenplatz Großkölnstraße (Kleinkölnstraße bis 01108 Aachen 1800,00 MK IV-V 30 Mefferdatisstraße) 01128 Aachen Theaterplatz (nördliche Bebauung) 1700,00 MK IV-V 30 Kapuzinergraben (Hartmannstraße bis ca. 01114 Aachen 1700,00 MI/MK IV-V 30 Theaterplatz) 01264 Aachen Kreuzungsbereich Wespienstraße / Reihstraße 1600,00 MI IV-V 30 01100 Aachen Blondelstraße / Willy-Brandt-Platz 1500,00 MI/MK IV-V 30 01104 Aachen Dahmengraben 1500,00 MI III-IV 30 Kapuzinergraben (ca. -

Camelbeeck Seismicity Fidgeo-3866

Historical Earthquakes, Paleoseismology, Neotectonics and Seismic Hazard: New Insights and Suggested Procedures DOI: 10.23689/fidgeo-3866 How well does known seismicity between the Lower Rhine Graben and southern North Sea reflect future earthquake activity? Thierry Camelbeeck1, Kris Vanneste1, Koen Verbeek1, David Garcia-Moreno1,2, Koen van Noten1 & Thomas Lecocq1 1 Royal Observatory of Belgium: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2 University of Ghent: [email protected] Abstract th Since the 14 century, moderate seismic activity with 14 earthquakes of magnitude MW≥5.0 occurred in Western Europe in a region extending from the Lower Rhine Graben (LRG) to the southern North Sea. In this paper, we investigate how well this seismic activity could reflect that of the future. The observed earthquake activity in the LRG is continuous and concentrates on the Quaternary normal faults delimiting the LRG, which are also the source of large surface rupturing Holocene and Late Pleistocene earthquakes. The estimated magnitude of these past earthquakes ranges from 6.3±0.3 to 7.0±0.3 while their average recurrence on individual faults varies from ten thousand to a few ten thousand years, which makes foreseeing future activity over the long-term possible. Three of the largest historical earthquakes with MW≥5.5 occurred outside the LRG. Late Quaternary activity along the fault zones suspected to be the source of two of these earthquakes, i.e. the 1580 Strait of Dover and 1692 northern Belgian Ardennes earthquakes, is very elusive if it exists. -

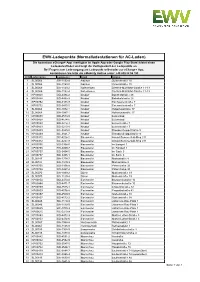

EWV-Ladepunkte (Normalladestationen Für AC-Laden)

EWV-Ladepunkte (Normalladestationen für AC-Laden) Die kostenlose eCharge+ App (verfügbar im Apple App oder Google Play Store) bietet einen Ladesäulenfinder und zeigt die Verfügbarkeit der Ladepunkte an. Bei Fragen zum Ladevorgang am Ladepunkt selbst oder zur eCharge+ App, kontaktieren Sie bitte die eMobility Hotline unter: +49 800 22 55 793 LFD Ladestation Ladepunkt Stadt Straße 1 SL00064 BA-1132-8 Aachen Zollernstraße 10 2 SL00064 BA-1153-0 Aachen Zollernstraße 10 3 SL00069 BA-1143-2 Aldenhoven Dietrich-Mühlfahrt-Straße 11-13 4 SL00069 BA-1152-4 Aldenhoven Dietrich-Mühlfahrt-Straße 11-13 5 KP00848 BD-4494-2 Alsdorf Bahnhofstraße 28 6 KP00848 BD-4495-9 Alsdorf Bahnhofstraße 28 7 KP00752 BD-3434-9 Alsdorf Eschweilerstraße 7 8 KP00752 BD-3435-5 Alsdorf Eschweilerstraße 7 9 SL00068 BA-1072-1 Alsdorf Hubertusstraße 17 10 SL00068 BA-1087-1 Alsdorf Hubertusstraße 17 11 KP00858 BD-4573-9 Alsdorf Luisenbad 12 KP00858 BD-4574-5 Alsdorf Luisenbad 13 KP00823 BD-3212-1 Alsdorf Luisenstraße 7 14 KP00823 BD-3213-8 Alsdorf Luisenstraße 7 15 KP00439 BC-3840-0 Alsdorf Theodor-Seipp-Straße 9 16 KP00439 BC-3841-7 Alsdorf Theodor-Seipp-Straße 9 17 KP00312 BC-4226-2 Baesweiler Arnold-Sommerfeld-Ring 211 18 KP00312 BC-4227-9 Baesweiler Arnold-Sommerfeld-Ring 211 19 KP00755 BD-3458-0 Baesweiler Im Bongert 1 20 KP00755 BD-3459-7 Baesweiler Im Bongert 1 21 KP00757 BD-3454-5 Baesweiler Im Sack 3 22 KP00757 BD-3455-1 Baesweiler Im Sack 3 23 SL00187 BA-1378-7 Baesweiler Mariastraße 8 24 SL00187 BA-1379-3 Baesweiler Mariastraße 8 25 KP00756 BD-3456-8 Baesweiler Peterstraße -

Amtsblatt Nr. 04 Vom 11. Februar 2021

Amtliches Mitteilungsblatt für Bürgerinnen und Bürger der Stadt Alsdorf Jahrgang Alsdorf, Nummer: Verleger und Herausgeber: Stadt Alsdorf Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, A 13 ‐ Amt für Kultur und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Postanschrift: das Amtsblatt – Amtliche Mitteilungsblatt der Stadt Alsdorf ist das gesetzlich Hubertusstraße 17 52477 Alsdorf vorgeschriebene Bekanntmachungsorgan der Stadt. Telefon: 0 24 04 / 50 ‐ 294 FAX: 0 24 04 / 50 ‐ 303 Homepage: www.alsdorf. .de Das Amtsblatt wird im Internet kostenfrei veröffentlicht auf der Homepage E‐Mail: der Stadt Alsdorf unter www.alsdorf.de. [email protected] Verantwortlich: Der Bürgermeister Mit freundlichen Grüßen Veröffentlichung: . Aushang im Rathausfoyer . Mitnahme im Rathausfoyer Alfred Sonders . im Internet abrufbar unter www.alsdorf.de (im Bereich Bürgermeister “Aktuelles”) ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN Allgemeine Besuchszeiten: Mo. ‐ Fr. 8.30 ‐ 12.00 Uhr Mi. 14.00 ‐ 18.00 Uhr und nach Vereinbarung Besuchszeiten Meldeamt: Mo./Di./Do. 7.30 - 16.00 Uhr Mi. 7.30 - 18.00 Uhr Fr. 7.30 - 12.00 Uhr Besuchszeiten Sozialamt: Mo./Di./Do./Fr. 8.30 - 12.00 Uhr Mi. 14.00 - 18.00 Uhr ansonsten ausschließlich nach telefonischer Vereinbarung Besuchszeiten Asylstelle: Di./Fr. 8.30 - 12.00 Uhr Mi. 14.00 - 18.00 Uhr ansonsten ausschließlich nach telefonischer Vereinbarung Amtliches Mitteilungsblatt der Stadt Alsdorf - Amtsblatt / 11. Februar 2021 / Nr. 04 / Seite 27 B e k a n n t m a c h u n g Der Entwurf der Haushaltssatzung der Stadt Alsdorf einschließlich Anlagen für das Haushaltsjahr 2021 liegt gemäß § 80 Abs. 3 Gemeindeordnung für das Land Nordrhein- Westfalen in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 14. Juli 1994 (GV NRW S. 666/SGV NRW 2023) in der zurzeit geltenden Fassung ab dem 02.