Complete Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rudy Kousbroek in De Essayistisch-Humanistische Traditie Z1291-Revisie2 HE22 07-11-17 16:06 Pagina 2 Z1291-Revisie2 HE22 07-11-17 16:06 Pagina 3

Z1291-revisie2_HE22 07-11-17 16:06 Pagina 1 Rudy Kousbroek in de essayistisch-humanistische traditie Z1291-revisie2_HE22 07-11-17 16:06 Pagina 2 Z1291-revisie2_HE22 07-11-17 16:06 Pagina 3 Rudy Schreijnders Rudy Kousbroek in de essayistisch-humanistische traditie Humanistisch Erfgoed 22 HUMANISTISCH HISTORISCH CENTRUM PAPIEREN TIJGER Z1291-revisie2_HE22 07-11-17 16:06 Pagina 4 Foto achterkant Op de achterflap van Terug naar Negri Pan Erkoms (Meulenhoff, 1995) staat een foto van Rudy Kousbroek, zwemmend in het Tobameer op Sumatra. Pauline Wesselink fotografeerde Rudy Schreijnders, bijna twintig jaar later, zwem- mend in hetzelfde meer. Vormgeving omslag: Marc Heijmans Boekverzorging: Zefier Tekstverwerking Drukwerk: Wöhrmann B.V. © Rudy Schreijnders © Stichting Uitgeverij Papieren Tijger ISBN 978 90 6728 334 2 NUR 715 Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in eni- ge vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopie of op andere manier; zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. www.uvh.nl/humanistisch-historisch-centrum www.papierentijger.org Z1291-revisie2_HE22 07-11-17 16:06 Pagina 5 Rudy Kousbroek in de essayistisch-humanistische traditie Rudy Kousbroek in the essayistic-humanist tradition (with a Summary in English) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit voor Humanistiek te Utrecht op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, prof. dr. Gerty Lensvelt-Mulders ingevolge het besluit van het College voor Promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op 20 december 2017 om 10.30 uur door Rudy Schreijnders geboren op 13 april 1950, te Amsterdam Z1291-revisie2_HE22 07-11-17 16:06 Pagina 6 Promotor: prof. -

Tilburg University Political Discontent

Tilburg University Political discontent in the Netherlands in the first decade of the 21th century Brons, C.R. Publication date: 2014 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Brons, C. R. (2014). Political discontent in the Netherlands in the first decade of the 21th century. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. sep. 2021 Political discontent Political in the Netherlands first decade of 21th century Political discontent LL B M R in the Netherlands in the first decade of the 21th century G Political discontent in the Netherlands in the first decade of the 21th century This book introduces a refreshing perspective on the popular idea that citizens’ political discontent is on the rise. Citizens’ perspectives on politics are studied thoroughly through survey studies and in-depth interviews. -

Kunst in Opdracht Zevende Expositie | Art Fund Nyenrode | Januari - Mei 2017 Een Unieke Selectie Uit De Kunstcollectie Van Postnl

Kunst in Opdracht zevende expositie | Art Fund Nyenrode | januari - mei 2017 een unieke selectie uit de kunstcollectie van PostNL 1 Kunst en Nyenrode Het organiseren van kunstexposities op Nyenrode is onder de naam Art Fund Nyenrode begonnen als een klein initiatief van een bescheiden groep alumni, twee jaar geleden. Zij toonden zich enthousiaste kunstliefhebbers met veel ambitie en organiseerden destijds de eerste tentoonstelling met foto’s verzameld door een Nyenrode alumnus. Er had in de jaren daarvoor geen kunst gehangen aan de muren van het Albert Heijn gebouw, dus werden her en der aanpassingen gedaan Kunst in Opdracht om de ruimtes geschikt te maken voor exposities. Het bleek een dankbare investering want de Kunstzinnig verleden en heden ene tentoonstelling volgde de andere op. Museale stukken en soms zelfs kwetsbare kunstuitingen waren op onze gangen plotseling te bewonderen. Een aantal studenten ging zich verdiepen in de tentoongestelde kunst en ontpopten zich als gidsen We zijn zeer verheugd om met deze inmiddels zevende Art Fund Nyenrode tentoonstelling een voor de bezoekers. Dat was ook nieuw. Dit op zich was al een uitzonderlijke prestatie maar daar bedrijfskunstcollectie van een van Nyenrode’s Founding Father te kunnen tonen. Om juister te zijn bleef het niet bij. Het aanbod was zo interessant dat lezers van de Volkskrant zich in een oogwenk van een rechtsopvolger van de ‘Dienst der P.T.T.’, die in 1946 één van de 39 grondleggers was van wat inschreven voor exclusieve rondleidingen. Nyenrode werd een kleine galerie waarbij sommige kunst destijds het Nederlands Opleidings-Instituut voor het Buitenland heette. Nu inmiddels uitgegroeid tot ook te koop was – en ook gekocht werd. -

Hermanus Goijers

Een Rapport Van De Genealogie Van HERMANUS GOIJERS Gecreërd op 30 april 2018 "The Complete Genealogy Reporter" © 2006-2013 Nigel Bufton Software under license to MyHeritage.com Family Tree Builder INHOUD 1. NAKOMELINGEN 2. DIRECTE RELATIES 3. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over EMMA THEUNIS 4. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over SUZANNA PAULINA ZINDEL 5. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over MARINA DE JONG 6. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over SYLVIA GEERTRUIDA JOHANNA PRINS 7. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over BERNULPHUS JOHANNES LOS 8. STAMBOMEN 9. INDEX VAN PLAATSEN 10. INDEX VAN DATA 11. INDEX VAN INDIVIDUEN 1. NAKOMELINGEN Hermanus Goijers111 +Ida Mignon112 Jozef Anton Johan Goijers (ongehuwd)107 Franciscus Goijers108 +Catharina Maria Johanna Pico109 Catharina Cornelia Maria Goijers102 Alexander Franciscus Goijers103 Cornelis Petrus Goijers104 +Emma Theunis105 Johanna Cornelia Catharina Goijers94 +Arthur Erich Max Ballin95 Johanna Emma Henriëtte Ballin68 +Frits Brandenburg69 Mireïlle Brandenburg39 ...(1) +Eli Gholam70 Michel Gholam41 Heinz Adolf Ballin71 +Annemaria Kayser-Petterson72 Markus Ballin43 Christof Ballin44 Patricia Ballin45 ...(2) Johannes Hubertus Ballin73 +Pamela Onbekend74 Jennifer Ballin47 Henriëtte Johanna Goijers96 Frans Hendrik Willem Goijers97 +Suzanna Paulina Zindel98 Jerome Goijers75 +Marina de Jong76 Jeffrey Goijers48 ...(3) Saskia Goijers50 ...(4) Enid Goijers77 Anke Goijers79 Cornelis Johannes Goijers99 +Laura Böck100 Erik Charles Goijers81 +Baps Cop82 Laura Goijers52 ...(5) Glenn Goijers54 ...(6) Irma Goijers83 Robert Carl Goijers84 +Nanny Grace -

Hermanus Goijers

Een Rapport Van De Genealogie Van HERMANUS GOIJERS Gecreërd op 12 januari 2014 "The Complete Genealogy Reporter" © 2006-2013 Nigel Bufton Software under license to MyHeritage.com Family Tree Builder INHOUD 1. NAKOMELINGEN 2. DIRECTE RELATIES 3. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over EMMA THEUNIS 4. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over SUZANNA PAULINA ZINDEL 5. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over MARINA DE JONG 6. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over SYLVIA GEERTRUIDA JOHANNA PRINS 7. INDIRECTE VERWANTSCHAP over BERNULPHUS JOHANNES LOS 8. STAMBOMEN 9. INDEX VAN PLAATSEN 10. INDEX VAN DATA 11. INDEX VAN INDIVIDUEN 1. NAKOMELINGEN Hermanus Goijers107 +Ida Mignon108 Jozef Anton Johan Goijers (ongehuwd)103 Franciscus Goijers104 +Catharina Maria Johanna Pico105 Catharina Cornelia Maria Goijers98 Alexander Franciscus Goijers99 Cornelis Petrus Goijers100 +Emma Theunis101 Johanna Cornelia Catharina Goijers90 +Arthur Erich Max Ballin91 Johanna Emma Henriëtte Ballin64 +Frits Brandenburg65 Mireïlle Brandenburg36 ...(1) +Eli Gholam66 Michel Gholam38 Heinz Adolf Ballin67 +Annemaria Kayser-Petterson68 Markus Ballin40 Christof Ballin41 Patricia Ballin42 ...(2) Johannes Hubertus Ballin69 +Pamela Onbekend70 Jennifer Ballin44 Henriëtte Johanna Goijers92 Frans Hendrik Willem Goijers93 +Suzanna Paulina Zindel94 Jerome Goijers71 +Marina de Jong72 Jeffrey Goijers45 ...(3) Saskia Goijers47 ...(4) Enid Goijers73 Anke Goijers75 Cornelis Johannes Goijers95 +Laura Böck96 Erik Charles Goijers77 +Baps Cop78 Laura Goijers49 ...(5) Glenn Goijers51 ...(6) Irma Goijers79 Robert Carl Goijers80 +Nanny Grace -

VOC in East Indies 1600 – 1800 the Path to Dominance

MASARYK UNIVERSITY Faculty of Social Studies Department of International Relations and European Studies The Dutch Trading Company – VOC In East Indies 1600 – 1800 The Path to Dominance Master Thesis Supervisor: Author: Mgr. et Mgr. Oldřich Krpec, Ph.D Prilo Sekundiari Brno, 2015 0 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis I submit for assessment is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Date : Signature ………………… 1 Abstract: Since the arrival of the European in Asia, the economic condition in Asia especially in Southeast Asia has changed drastically. The European trading company such the Dutch’s VOC competing with the other traders from Europe, Asia, and local traders for dominance in the trading sphere in East Indies. In 17th century, the Dutch’s VOC gained its golden age with its dominance in East Indies. The purpose of this thesis is to find out what was the cause of the VOC success during its time. Keywords: VOC, Dutch, Company, Politics, Economy, Military, Conflicts, East Indies, Trade, Spices, Dominance Language used: English 2 Acknowledgements: I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. et Mgr. Oldřich Krpec, Ph.D., Prof. Dr. Djoko Suryo for all of his advices, matur nuwun... My friends; Tek Jung Mahat, and Weronika Lazurek. Thank you.... Prilo Sekundiari 3 Table of Contents Glossary________________________________________________________6 Introduction_____________________________________________________8 1. Background and Historical Setting 1.1. Geographical Condition___________________________________12 1.1.1. Sumatera ______________________________________________13 1.1.2. Kalimantan____________________________________________ 15 1.1.3. -

Persona Non Grata

Persona non grata Willem Oltmans bron Willem Oltmans, Persona non grata. Papieren Tijger, Breda 1996 (2de druk) Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/oltm003pers02_01/colofon.php © 2014 dbnl / Willem Oltmans Stichting 5 Revenge is a kind of wild justice, which the more man's nature runs to, the more ought law to weed it out. Francis Bacon Willem Oltmans, Persona non grata 7 Voorwoord In 1994 ben ik 41 jaar journalist. In dit boek is in een notedop beschreven hoe ik 38 jaar door de overheid en de inlichtingendiensten ben geterroriseerd in opdracht van Joseph Luns, nadat hij ongelijk kreeg in de kwestie Nieuw Guinea, precies zoals ik hem had voorspeld. Al in 1958 vluchtte ik naar de VS waar de achtervolging, zoals geheime documenten in 1991 zouden bewijzen, onverminderd werd voortgezet. Het uiteindelijke doel van mijn vijand was niet alleen om mijn werk als journalist onmogelijk te maken, maar om mij uiteindelijk tot de bedelstaf te brengen. Mijn ouders hadden me voldoende fondsen nagelaten, zodat ik deze ongelijke strijd tot 1990 heb kunnen volhouden. Toen vluchtte ik opnieuw, ditmaal naar Zuid-Afrika, maar ook daar werd de terreur voortgezet. In 1992 ging ik gedwongen naar Amsterdam terug en probeer me in een studio van zes bij zes in de Jordaan staande te houden van een minimumuitkering van 1.240 gulden per maand. Mijn vrienden hebben me sedert jaren geadviseerd me niet langer aan de regels te houden waar de overheid nooit anders heeft gedaan dan mijn rechten als burger en journalist met voeten te treden. Maar dan is er altijd weer de homunculus, het kleine mannetje in mijn brein, door Leibnitz eens omschreven als de demon of de kabouter, die me influistert ‘Doe anderen niet aan wat zij jou aandoen’. -

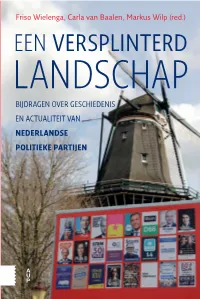

Een Versplinterd Landschap Belicht Deze Historische Lijn Voor Alle Politieke NEDERLANDSE Partijen Die in 2017 in De Tweede Kamer Zijn Gekozen

Markus Wilp (red.) Wilp Markus Wielenga, CarlaFriso vanBaalen, Friso Wielenga, Carla van Baalen, Markus Wilp (red.) Het Nederlandse politieke landschap werd van oudsher gedomineerd door drie stromingen: christendemocraten, liberalen en sociaaldemocraten. Lange tijd toonden verkiezingsuitslagen een hoge mate van continuïteit. Daar kwam aan het eind van de jaren zestig van de 20e eeuw verandering in. Vanaf 1994 zette deze ontwikkeling door en sindsdien laten verkiezingen EEN VERSPLINTERD steeds grote verschuivingen zien. Met de opkomst van populistische stromingen, vanaf 2002, is bovendien het politieke landschap ingrijpend veranderd. De snelle veranderingen in het partijenspectrum zorgen voor een over belichting van de verschillen tussen ‘toen’ en ‘nu’. Bij oppervlakkige beschouwing staat de instabiliteit van vandaag tegenover de gestolde LANDSCHAP onbeweeglijkheid van het verleden. Een dergelijk beeld is echter een ver simpeling, want ook in vroeger jaren konden de politieke spanningen BIJDRAGEN OVER GESCHIEDENIS hoog oplopen en kwamen kabinetten regelmatig voortijdig ten val. Er is EEN niet alleen sprake van discontinuïteit, maar ook wel degelijk van een doorgaande lijn. EN ACTUALITEIT VAN VERSPLINTERD VERSPLINTERD Een versplinterd landschap belicht deze historische lijn voor alle politieke NEDERLANDSE partijen die in 2017 in de Tweede Kamer zijn gekozen. De oudste daarvan bestaat al bijna honderd jaar (SGP), de jongste partijen (DENK en FvD) zijn POLITIEKE PARTIJEN nagelnieuw. Vrijwel alle bijdragen zijn geschreven door vertegenwoordigers van de wetenschappelijke bureaus van de partijen, waardoor een unieke invalshoek is ontstaan: wetenschappelijke distantie gecombineerd met een beschouwing van ‘binnenuit’. Prof. dr. Friso Wielenga is hoogleraardirecteur van het Zentrum für NiederlandeStudien aan de Westfälische Wilhelms Universität in Münster. LANDSCHAP Prof. -

Download Pdf

KINERJA REGULATOR PENYIARAN INDONESIA Penilaian atas Derajat Demokrasi, Profesionalitas, dan Tata Kelola KINERJA REGULATOR PENYIARAN INDONESIA Penilaian atas Derajat Demokrasi, Profesionalitas, dan Tata Kelola Tim Penulis Rahayu Bayu Wahyono Puji Rianto Iwan Awaluddin Yusuf Saifudin Zuhri Moch. Faried Cahyono Amir Effendi Siregar PR2Media Yayasan Tifa 2014 KINERJA REGULATOR PENYIARAN INDONESIA Penilaian atas Derajat Demokrasi, Profesionalitas, dan Tata Kelola Penulis | Rahayu | Bayu Wahyono | Puji Rianto | Iwan Awaluddin Yusuf | Saifudin Zuhri | Moch. Farid Cahyono | Amir Effendi Siregar Penyunting | Intania Poerwaningtias Perancang Sampul | Dhanan Arditya Tata Letak | Muklis Diterbitkan oleh Pemantau Regulasi dan Regulator Media (PR2Media) bekerja sama dengan Yayasan Tifa. Dilarang memperbanyak sebagian atau seluruh isi terbitan buku ini dalam bentuk apapun tanpa izin tertulis dari Yayasan Tifa. Tidak untuk diperjualbelikan. Cetakan Pertama, 2014 Perpustakaan Nasional RI: Katalog Dalam Terbitan (KDT) Rahayu, dkk xviii + 167 halaman; 14,8 x 21 cm ISBN 978-602-97839-5-7 1. Regulator 2. Penyiaran 3. Demokrasi Pemantau Regulasi dan Regulator Media (PR2Media) JL. Solo KM 8, Nayan No. 108A, Maguwoharjo, Depok, Sleman, Yogyakarta, 55282 Telp. (0274) 489283, Fax. (0274) 486872, e-mail: [email protected] MENILAI DAN MEMBANGUN REGULATOR PENYIARAN oleh Amir Effendi Siregar Ketua Pemantau Regulasi dan Regulator Media (PR2MEDIA) Buku hasil penelitian ini adalah buku keenam yang telah diterbitkan oleh PR2MEDIA bekerja sama dengan Yayasan TIFA dan merupakan kelanjutan dari buku sebelumnya yang berjudul Kepemilikan dan Intervensi Siaran (2014). Buku ini dibuat berdasarkan hasil penelitian yang berjudul Kinerja Regulator Penyiaran Indonesia: Penilaian terhadap Derajat Demokrasi, Profesionalitas, dan Tata Kelola. Di Indonesia, berdasarkan Undang-Undang Penyiaran, terdapat 2 regulator utama penyiaran, yaitu Kementerian Komunikasi dan Informatika (Kemenkominfo) dan Komisi Penyiaran Indonesia (KPI). -

“The Loneliest Spot on Earth”: Harry Mulisch's Literary Experiment in Criminal Case 40/61

“The loneliest spot on Earth”: Harry Mulisch’s Literary Experiment ... 33 “The loneliest spot on Earth”: Harry Mulisch’s Literary Experiment in Criminal Case 40/61 SANDER BAX Tilburg University Departement Cultuurwetenschappen Universiteit Tilburg Concordiastraat 52, 3551EN, Utrecht, Nederland [email protected] Abstract. Harry Mulisch’s Criminal Case 40/61 is often regarded as an early representative of the movement of New Journalism and as an example for what we nowadays call ‘literary non-fiction.’ In this essay, I will argue that this classification does not do justice to the complexity of the literary experiments that Mulisch is trying out in this text. In Criminal Case 40/61 Mulisch develops a highly personal and literary way to write about Adolf Eichmann. A problem as complex as the essence of evil, he claims, can not be comprehended with the methods of journalism and history only, the Eichmann enigma calls for a new language. I will outline a number of techniques Mulisch used to achieve this goal. In this text, Mulisch uses an autofictional construction as well as a metaphorical way of thinking and writing that transgresses the journalistic or historicist mimetic-referential and discursive ways of writing. Central to Mulisch’s literary method are two principles: that of the invention of language and images and that of radical identification. Keywords: literary non-fiction; New Journalism; fictionality; autofiction; Harry Mulisch; Adolf Eichmann 1. Introduction The works of the recently deceased Dutch writer Harry Mulisch are fascinating for several reasons. Time and again Mulisch leaves the literary domain to involve himself in public affairs. -

Tvg Nr 2-09.Indd

194 Mark Leon de Vries Pompeï 1956. Een van de eerste gesprekken van Oltmans met Soekarno. V.l.n.r.: de I ndonesische minister van Buitenlandse Zaken Roeslan Abdoelgani, de Amerikaanse adviseur van Soekarno Joe Borkin, Soekarno en Oltmans. Bron: Koninklijke Bibliotheek, archief Willem Oltmans Guest (guest) IP: 170.106.203.74 On: Mon, 04 Oct 2021 01:46:19 195 Eenmansfractie Oltmans Op de barricaden voor de overdracht van Nieuw-Guinea Wouter Meijer De eigenzinnige journalist Willem Oltmans speelde een Toch is Oltmans’ rol in het conflict interes- sant. Hij was een van de weinigen in Nederland zeer opmerkelijke rol in de kwestie Nieuw-Guinea, die in de die zich openlijk verzetten tegen het gevoerde Nieuw-Guinea-beleid. Hij had lak aan de ge- literatuur te weinig aandacht heeft gekregen. Waarom en vestigde orde, hechtte niet aan partijgebonden- heid en legde overal contacten. Die eigenzinnig- op welke manier hield Oltmans zich met het conflict bezig? heid is hem nogal eens kwalijk genomen, maar maakte hem in de kwestie Nieuw-Guinea tot En waarom heeft hij niet meer invloed gehad? een belangwekkende, onberekenbare factor. Hij was voor een snelle overdracht van het eiland aan Indonesië, opereerde vaak tussen de linies en werd vanwege zijn controversiële mening in Inleiding Nederland als een buitenstaander beschouwd. ‘Ik trek me geen flikker aan van wat de Neder- Dit artikel is een impressie van Oltmans’ po- landse kranten schrijven, ik ga altijd zelf kijken’, ging de impasse, waarin de kwestie sinds 1956 zei Willem Oltmans tegen Theo van Gogh in verkeerde, te doorbreken en geeft inzicht in zijn een reeks interviews die Van Gogh in 1997 met beweegredenen en wijze van optreden. -

Slijpen Aan De Geest John Slijpen Kroon VIJFTIG JAAR NRC HANDELSB LAD Aan Deslijpengeest Aan Degeest VIJFTIG JAAR NRC HANDELSBLAD

Slijpen aan de geest John Slijpen Kroon VIJFTIG JAAR NRC HANDELSB LAD aan deSlijpengeest aan degeest VIJFTIG JAAR NRC HANDELSBLAD 2021 Prometheus Amsterdam © 2021 John Kroon Omslagontwerp Tessa van der Waals Foto omslag Maurice Boyer Lithografie afbeeldingen bfc, Bert van der Horst, Amersfoort Zetwerk Mat-Zet bv, Huizen www.uitgeverijprometheus.nl isbn 978 90 446 4131 8 Woord vooraf. Een nieuw dagblad Op 1 oktober 1970 werd een nieuwe krant opgericht. Het in Amsterdam ge- vestigde Algemeen Handelsblad en de Rotterdamse nrc werden samenge- voegd tot nrc Handelsblad. Twee oude, liberale avondkranten, gesticht in respectievelijk 1828 en 1844, die beide noodlijdend waren. Het was een fusie uit noodzaak. Zo ontstond een nieuw landelijk dagblad dat voorop zou lopen bij de ontzuiling die zich in die jaren in Nederland manifesteerde. Vijftig jaar later blijkt nrc Handelsblad springlevend te zijn en een stevige positie te hebben op de dagbladmarkt. Dit boek gaat over de journalistieke geschiedenis van nrc Handelsblad. Zeven hoofdredacteuren telde de krant sinds ze werd gesticht. Zij werden met de meest uiteenlopende situaties geconfronteerd. Conflicten en harmo- nieuze contacten met het Koninklijk Huis, ruzies met uitgevers, plagiaataffai- res, rechtszaken, stakende redacteuren, columnisten die voor tumult zorg- den, cartoonisten die vrolijkheid en ergernis brachten, de ene hoofdredacteur die werd beschuldigd van medeplichtigheid aan een moord op een politicus en de andere die te horen kreeg dat hij het leven van de koningin had gered. Saai was het zelden op en rond de redactie. Tussendoor werd van nrc Handelsblad meestal een heel behoorlijke krant gemaakt; een dagblad dat oog had voor de achtergronden van het nieuws, een rijk scala aan opinies en commentaren bracht, veel aandacht aan cultuur schonk en ook steeds nadrukkelijker onderzoeksjournalistiek tot zijn kern- taak is gaan rekenen.