Early Bronze Age Pottery Workshops Around Pergamon: a Model for Pottery Production in the 3Rd Millennium BC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE POLITICAL CHANGES in IONIA AFTER the REVOLT ßß42 And

APPENDIX 11 THE POLITICAL CHANGES IN IONIA AFTER THE REVOLT §§42 and 43.3 throw important light on the Persian attitude to their subject peoples in the west, and certainly on Artaphrenes as a shrewd administrator. The revolt had taken six years and considerable mil- itary effort to suppress. Three political changes are now made, two by the satrap, the third by Mardonius. Another account of it sur- vives, DS 10.25.4, where the third is also ascribed to Artaphrenes: ÑEkata›ow ı MilÆsiow presbeutØw épestalm°now ÍpÚ t«n ÉI≈nvn, ±r≈thse diÉ ∂n afit¤an épiste› aÈto›w ı ÉArtaf°rnhw. toË d¢ efipÒntow, mÆpote Íp¢r œn katapolemhy°ntew kak«w ¶payon mnhsikakÆsvsin, OÈkoËn, ¶fhsen, efi tÚ pepony°nai kak«w tØn épist¤an peripoie›, tÚ paye›n êra eÔ poiÆsei tåw pÒleiw P°rsaiw eÈnooÊsaw. épodejãmenow d¢ tÚ =hy¢n ı ÉArtaf°rnhw ép°dvke toÁw nÒmouw ta›w pÒlesi ka‹ taktoÁw fÒrouw katå dÊnamin §p°tajen.1 Artaphrenes had to reimpose his authority, but also had the practical interest of ensuring stability, particularly economic stability, which in turn meant that tribute could flow in: cf Starr (1975) 82, Briant (1996) 511, and other references cited on êndrew, §19.3. We may accept §42.1, that he summoned representatives from each polis, in view of the arbitration requirement; but we can accept Diodorus to the extent that Hecataeus was the, or one of the, representative(s) from Miletus: he had influence there, and could be presented to the Persians as someone who had not fully supported the revolt (5.36, 125; pp. -

Achaemenid Grants of Cities and Lands to Greeks: the Case of Mentor and Memnon of Rhodes Maxim M

Achaemenid Grants of Cities and Lands to Greeks: The Case of Mentor and Memnon of Rhodes Maxim M. Kholod HE GRANTS of cities and lands to foreigners, including Greeks, who had provided and/or would in the future T provide important services to the Persian kings and satraps were a fairly common practice in the Achaemenid Empire.1 A portion of evidence for such grants concerns Asia Minor. For example, Cyrus the Great is said to have granted seven cities in Asia Minor to his friend Pytharchus of Cyzicus.2 The Spartan king Demaratus, after he had been allowed to dwell in Persia, received from Darius I and probably then from Xerxes lands and cities, among them Teuthrania and Halisarna, where his descendants, the Demaratides, still were in power at the beginning of the fourth century.3 Gongylus of Eretria, who had been expelled from his home city as an adherent of the Persians, received from Xerxes the cities Gambrium, Palaegambrium, 1 On these grants see in detail M. A. Dandamayev and V. G. Lukonin, Kultura i ekonomika drevnego Irana (Moscow 1980) 138–142 (Engl. transl.: Cambridge 1989); P. Briant, “Dons de terres et de villes: L’Asie Mineure dans le contexte achéménide,” REA 87 (1985) 51–72, and From Cyrus to Alexander (Winona Lake 2002) 561–563, 969; Ch. Tuplin, “The Administration of the Achaemenid Empire,” in I. Carradice (ed.), Coinage and Administration in the Athenian and Persian Empires (Oxford 1987) 133–137; G. Herman, Ritualised Friendship and the Greek City (Cambridge 1987) 106–115; P. Debord, L’Asie Mineure au IVe siècle (Bordeaux 1999) 189–193; H. -

JOURNAL of GREEK ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 4 2019

ISSN: 2059-4674 Journal of Greek Archaeology Volume 4 • 2019 Journal of Greek Archaeology Journal of Greek Archaeology Volume 4: Editorial������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� v John Bintliff Prehistory and Protohistory The context and nature of the evidence for metalworking from mid 4th millennium Yali (Nissyros) ������������������������������������������������������������������ 1 V. Maxwell, R. M. Ellam, N. Skarpelis and A. Sampson Living apart together. A ceramic analysis of Eastern Crete during the advanced Late Bronze Age ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 31 Charlotte Langohr The Ayios Vasileios Survey Project (Laconia, Greece): questions, aims and methods����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 67 Sofia Voutsaki, Corien Wiersma, Wieke de Neef and Adamantia Vasilogamvrou Archaic to Hellenistic Journal of The formation and development of political territory and borders in Ionia from the Archaic to the Hellenistic periods: A GIS analysis of regional space ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 96 David Hill Greek Archaeology Multi-faceted approaches -

The Fiscal Politics of Pergamon, 188-133 B.C.E

“The Skeleton of the State:” The Fiscal Politics of Pergamon, 188-133 B.C.E. By Noah Kaye A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California-Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emily Mackil Professor Erich Gruen Professor Nikolaos Papazarkadas Professor Andrew Stewart Professor Dylan Sailor Fall 2012 Abstract “The Skeleton of the State:” the Fiscal Politics of Pergamon, 188-133, B.C.E. by Noah Kaye Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Emily Mackil, Chair In 188 B.C.E., a Roman commission awarded most of Anatolia (Asia Minor) to the Attalid dynasty, a modest fiefdom based in the city of Pergamon. Immediately, the Roman commissioners evacuated along with their force of arms. Enforcement of the settlement, known as the Treaty of Apameia, was left to local beneficiaries, chiefly the Attalids, but also the island republic of Rhodes. The extraction of revenues and the judicious redistribution of resources were both key to the extension of Attalid control over the new territory and the maintenance of the empire. This dissertation is a study of the forms of taxation and public benefaction that characterized the late Attalid kingdom, a multiscalar state comprised of many small communities, most prominent among them, ancient cities on the Greek model of the polis. It argues that the dynasty’s idiosyncratic choices about taxation and euergetism help explain the success of the Attalid imperial project. They aligned interests and created new collectivities. -

ATLAS of CLASSICAL HISTORY

ATLAS of CLASSICAL HISTORY EDITED BY RICHARD J.A.TALBERT London and New York First published 1985 by Croom Helm Ltd Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 1985 Richard J.A.Talbert and contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Atlas of classical history. 1. History, Ancient—Maps I. Talbert, Richard J.A. 911.3 G3201.S2 ISBN 0-203-40535-8 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-71359-1 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-03463-9 (pbk) Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Also available CONTENTS Preface v Northern Greece, Macedonia and Thrace 32 Contributors vi The Eastern Aegean and the Asia Minor Equivalent Measurements vi Hinterland 33 Attica 34–5, 181 Maps: map and text page reference placed first, Classical Athens 35–6, 181 further reading reference second Roman Athens 35–6, 181 Halicarnassus 36, 181 The Mediterranean World: Physical 1 Miletus 37, 181 The Aegean in the Bronze Age 2–5, 179 Priene 37, 181 Troy 3, 179 Greek Sicily 38–9, 181 Knossos 3, 179 Syracuse 39, 181 Minoan Crete 4–5, 179 Akragas 40, 181 Mycenae 5, 179 Cyrene 40, 182 Mycenaean Greece 4–6, 179 Olympia 41, 182 Mainland Greece in the Homeric Poems 7–8, Greek Dialects c. -

This Book — the Only History of Friendship in Classical Antiquity That Exists in English

This book — the only history of friendship in classical antiquity that exists in English - examines the nature of friendship in ancient Greece and Rome from Homer (eighth century BC) to the Christian Roman Empire of the fourth century AD. Although friendship is throughout this period conceived of as a voluntary and loving relationship (contrary to the prevailing view among scholars), there are major shifts in emphasis from the bonding among warriors in epic poetry, to the egalitarian ties characteristic of the Athenian democracy, the status-con- scious connections in Rome and the Hellenistic kingdoms, and the commitment to a universal love among Christian writers. Friendship is also examined in relation to erotic love and comradeship, as well as for its role in politics and economic life, in philosophical and religious communities, in connection with patronage and the private counsellors of kings, and in respect to women; its relation to modern friendship is fully discussed. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 147.231.79.110 on Thu May 20 13:43:40 BST 2010. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 147.231.79.110 on Thu May 20 13:43:40 BST 2010. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 KEYTHEMES IN ANCIENT HISTORY Friendship in the classical world Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 147.231.79.110 on Thu May 20 13:43:40 BST 2010. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 KEY THEMES IN ANCIENT HISTORY EDITORS Dr P. -

ATARNEUS Güler ATEŞ

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.17218/hititsosbil.403817 PERGAMON’UN GÖLGESİNDE BİR KOMŞU KENT: ATARNEUS Güler ATEŞ1 Atıf/©: Ateş, Güler (2018). Pergamon’un Gölgesinde Bir Komşu Kent: Atarneus, itit Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, Yıl 11, Sayı 1, Haziran ss 325-342 Özet: Araştırmalar göstermektedir ki, antik eramon Kenti’nin oliti ve eonomi açıdan güçlenmesinin sonuçları yakın çevresine bire bir yansımakta ve bunun son olarak entle irlikte taşra da dinamik bir şekilde hızla gelişmekteydi. Pergamon kenti ile kırsalı arasındaki ilişkilerin yanı sıra, bir diğer önemli konu da kentte yaşanan siyasal olaylar ve entin Hellenistik Dönem’en itibaren kaydettiği hızlı gelişmenin komşu kentleri nasıl etkilediğidir. Pergamon'un siyasal ve ekonomik açıdan büyümesi, kırsal kesimlerde tarımsal faaliyetlerin artmasına neden olmuş; komşu kentler açısından ise bu gelişim bazıları için faydalı olurken bazılarının da sonun getirmiştir. Pergamon Krallığı kuruluncaya kadar komşusu Atarneus kentinin bölgede önemli bir yere sahip olduğu bilinmektedir. Atarneus'taki araştırmalarımızda ele geçirilen seramik parçalarına göre, burada tespit edilen en erken yerleşme MÖ 2. bin yıla inmektedir; MÖ 6. ve 5. yüzyıllarda ise hatırı sayılır büyüklükte bir yerleşime ulaşmıştır. Atarneus MÖ 4. yüzyılda – aynı yüzyıldaki kaynakların doğruladığı gibi (Diod. 13, 65, 4)– heybetli ve aşılması neredeyse imkansız surlarla korunuyordu. Metrelerce yükseklikteki surların koruduğu 24 hektarlık kent alanı, Philetairos zamanındaki Pergamon'dan bile daha büyüktü. MÖ 4. yüzyılda Atarneus’da hüküm süren ve yerel bir hanedan beyi olan Hermias'ın egemenliği altındaki bölge, Atarneus’dan itibaren kıyı bölgesini ve Bakırçay Ovası’nı da içine alacak büyüklükteydi. Ele geçirilen seramik parçalarına göre MÖ 3. yüzyılda Atarneus’un refah içinde bir kent olduğunu söyleyebiliriz. -

The Origins of Greek Mathematics1

The Origins of Greek Mathematics1 Though the Greeks certainly borrowed from other civilizations, they built a culture and civilization on their own which is The most impressive of all civilizations, • The most influential in Western culture, • The most decisive in founding mathematics as we know it. • The impact of Greece is typified by the hyperbole of Sir Henry Main: “Except the blind forces of nature, nothing moves in this world which is not Greek in its origin.”2 Including the adoption of Egyptian and other earlier cultures by the Greeks, we find their patrimony in all phases of modern life. Handicrafts, mining techniques, engineering, trade, governmental regulation of commerce and more have all come down to use from Rome and from Rome through Greece. Especially, our democrasies and dictatorships go back to Greek exemplars, as well do our schools and universities, our sports, our games. And there is more. Our literature and literary genres, our alphabet, our music, our sculpture, and most particularly our mathematics all exist as facets of 1 c 2000, G. Donald Allen 2Rede° Lecture for 1875, in J.A. Symonds, Studies of Greek Poets, London, 1920. Origins of Greek Mathematics 2 the Greek heritage. The detailed study of Greek mathematics reveals much about modern mathematics, if not the modern directions, then the logic and methods. The best estimate is that the Greek civilization dates back to 2800 BCE — just about the time of the construction of the great pyramids in Egypt. The Greeks settled in Asia Minor, possibly their original home, in the area of modern Greece, and in southern Italy, Sicily, Crete, Rhodes, Delos, and North Africa. -

Pergamon and Its Multi-Layered Cultural Landscape SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2017-2021

Pergamon and its Multi-Layered Cultural Landscape SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2017-2021 . TABLE OF CONTENTS PLAN PREPARATION TEAM ................................................................................................................................. 1 CONTRIBUTORS ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION AND PREPARATION PROCESS.......................................................................................... 2 1.1 AIM OF THE PLAN ................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 FACILITATING ELEMENT IN CONSERVATION: INHABITANTS OF BERGAMA, FRIENDS OF BERGAMA .... 3 1.3 LEGAL BASIS AND GROUNDS OF THE PLAN............................................................................................ 4 1.4 PREPARATION PROCESS AND APPROVAL OF THE PLAN ........................................................................ 7 2 BERGAMA: ENTRUSTMENT TO FUTURE GENERATIONs ............................................................................. 9 2.1 WORLD HERITAGE SITE: MULTI LAYERED CULTURAL LANDSCAPE OF BERGAMA ................................ 10 2.2 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT THAT CREATED THE UNIVERSAL VALUES OF BERGAMA ......................... 14 2.3 INSCRIPTION CRITERIA OF BERGAMA ON UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE LIST: ....................................... 32 2.4 INTEGRITY ........................................................................................................................................... -

Aristotle's Last Will and Testament Anton-Hermann Chroust

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 45 | Issue 4 Article 3 6-1-1970 Estate Planning in Hellenic Antiquity: Aristotle's Last Will and Testament Anton-Hermann Chroust Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Anton-Hermann Chroust, Estate Planning in Hellenic Antiquity: Aristotle's Last Will and Testament, 45 Notre Dame L. Rev. 629 (1970). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol45/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESTATE PLANNING IN HELLENIC ANTIQUITY: ARISTOTLE'S LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT Anton-Hermann Chroust I. Introduction The text of Aristotle's last will and testament is preserved in the writings of Diogenes Laertius,' Ibn An-Nadim,2 AI-Qifti Gamaladdin, and Ibn Abi Usaibi'a.4 Without question, this instrument is wholly authentic. Although in the course of its transmission it may have been somewhat mutilated or abridged, it remains the most revealing, as well as the most extensive, source of information among the few surviving original documents related to the life of Aristotle. It is safe to assume that the ancient biographers of Aristotle derived or inferred much of their information and data from this will. Concomitantly, this docu- ment supplies the modem historian with details that in many instances have been obscured, altered, or simply omitted in the traditional (and preserved) biog- raphies of Aristotle. -

Manipulating Late Hellenistic Coinage: Some Overstrikes and Countermarks on Bronze Coins of Pergamum Jérémie Chameroy

Manipulating Late Hellenistic Coinage: Some Overstrikes and Countermarks on Bronze Coins of Pergamum Jérémie Chameroy To cite this version: Jérémie Chameroy. Manipulating Late Hellenistic Coinage: Some Overstrikes and Countermarks on Bronze Coins of Pergamum. Chiron, Walter de Gruyter, 2016, pp.85-118. hal-02451369 HAL Id: hal-02451369 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02451369 Submitted on 23 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CHIRON MITTEILUNGEN DER KOMMISSION FÜR ALTE GESCHICHTE UND EPIGRAPHIK DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Sonderdruck aus Band 46 · 2016 DE GRUYTER INHALT DES 46. BANDES (2016) Thomas Blank, Treffpunkt, Schnittpunkt, Wendepunkt. Zur politischen und mu- sischen Symbolik des Areals der augusteischen Meta Sudans Jérémie Chameroy, Manipulating Late Hellenistic Coinage: Some Overstrikes and Countermarks on Bronze Coins of Pergamum Borja Díaz Ariño – Elena Cimarosti, Las tábulas de hospitalidad y patronato Charles Doyen, Ex schedis Fourmonti. Le décret agoranomique athénien (CIG I 123 = IG II–III2 1013) Eric Driscoll, Stasis and Reconciliation: Politics and Law in Fourth-Century Greece Werner Eck,Zur tribunicia potestas von Kaiser Decius und seinen Söhnen Pierre Fröhlich, Magistratures éponymes et système collégial dans les cités grecques aux époques classique et hellénistique Wolfgang Günther – Sebastian Prignitz, Ein neuer Jahresbericht über Baumaßnahmen am Tempel des Apollon von Didyma Rudolf Haensch – Achim Lichtenberger – Rubina Raja, Christen, Juden und Soldaten im Gerasa des 6. -

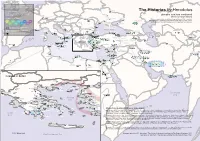

The Histories by Herodotus Chapter, a Hexagon with Light Border Is Drawn Near the Location the Character Hylaea Comes From

For each location mentioned in a chapter, a hexagon with dark border is drawn near that location. Dnieper For each character mentioned in a Gelonus The Histories by Herodotus chapter, a hexagon with light border is drawn near the location the character Hylaea comes from. placable locations mentioned Celts Danube Pyrene three or more times Chapter Color Scale: Gerrians Carpathian Mountains Tanaïs Where a region is dominated by a large settlement (like a capital), Far Scythia the settlement is generally used instead of the region to save space. I III V VII IX Some names in crowded locations on the map have been left out. Dacia Tyras Borysthenes II IV VI VIII Cremnoi Istros the place or the people was Illyria Scythian Neapolis mentioned explicitly Getae Marseille Odrysians Black Sea a character from nearby was Aléria Italy Mesambria Caucasus Massagetae Phasis mentioned Paeonia Sinop Pteria Caere Brygians Apollonia city or mountain location Mt. Haemus Caspian Byzantium Colchis Sea Sardinia Taranto Thyrea Sogdia Siris Velia Messapii Terme River Cyzicus Gordium Sybaris Crotone Cappadocia Sardis Armenia Messina Segesta Rhegium Greece Tigris Caspiane Tartessos Gela Pamphylia Parthia Carthage Selinunte Syracuse Milas Kaunos Cilicia Telmessos Nineveh Kamarina Lindos Posideion Xanthos Salamis Euphrates Kourion Ecbatana Amathus Gandhara Cyprus Tyre Sidon Cyrene Lotophagi Babylon Susa Barca Garamantes Macai Saïs Ienysos Heliopolis Petra Atlas Persepolis Asbystai Awjila Memphis Ammonians Egyptian Thebes Greece in detail Elephantine BC invasion b Myrkinos 480 y Xe rxes Red Macedonia Abdera Cicones Eïon Doriscus Sea Therma The Nile Olynthus Akanthos Thasos Cardia Sestos Pieria Vardar Samothrace Lampsacus Chalcidice Sane Imbros Abydos Pindus Mt.