Article on Alvar's Lithographs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalonia Accessible Tourism Guide

accessible tourism good practice guide, catalonia 19 destinations selected so that everyone can experience them. A great range of accessible leisure, cultural and sports activities. A land that we can all enjoy, Catalonia. © Turisme de Catalunya 2008 © Generalitat de Catalunya 2008 Val d’Aran Andorra Pirineus Costa Brava Girona Lleida Catalunya Central Terres de Lleida Costa de Barcelona Maresme Costa Barcelona del Garraf Tarragona Terres Costa de l’Ebre Daurada Mediterranean sea Catalunya Index. Introduction 4 The best destinations 6 Vall de Boí 8 Val d’Aran 10 Pallars Sobirà 12 La Seu d’Urgell 14 La Molina - La Cerdanya 16 Camprodon – Rural Tourism in the Pyrenees 18 La Garrotxa 20 The Dalí route 22 Costa Brava - Alt Empordà 24 Vic - Osona 26 Costa Brava - Baix Empordà 28 Montserrat 30 Maresme 32 The Cister route 34 Garraf - Sitges 36 Barcelona 38 Costa Daurada 40 Delta de l’Ebre 42 Lleida 44 Accessible transport in Catalonia 46 www.turismeperatothom.com/en/, the accessible web 48 Directory of companies and activities 49 Since the end of the 1990’s, the European Union has promoted a series of initiatives to contribute to the development of accessible tourism. The Catalan tourism sector has boosted the accessibility of its services, making a reality the principle that a respectful and diverse society should recognise the equality of conditions for people with disabilities. This principle is enshrined in the “Barcelona declaration: the city and people with disabilities” that to date has been signed by 400 European cities. There are many Catalan companies and destinations that have adapted their products and services accordingly. -

Social Structure of Catalonia

THE SOCIAL STRUCTURE OF CATALONIA By SALVADOR GINER 1984 THE ANGLO-CATALAN SOCIETY THE ANGLO-CATALAN SOCIETY OCCASIONAL PUBLICATIONS No 1. Salvador Giner. The Social Structure of Catalonia. No 2. J Salvat-Papasseit. Selected Poems. Translated with an Introduction by D. Keown and T. Owen. © Salvador Giner, 1980. Printed by The University of Sheffield Printing Unit. Cover design by Joan Gili. ISSN No. 0144-5863 ISBN No. 09507137 08 IN MEMORIAM JOSEP MARIA BATISTA I ROCA (1895-1978) Dr. J. M. Batista i Roca, founder member of the Anglo-Catalan Society and its first Honorary Life President, always hoped that the Society would at some stage be able to publish some of the work of its members and guest speakers. Unfortunately this was never possible during his lifetime, but now that the Society, with the help of a grant from Omnium Cultural, is undertaking the publication of Occasional Papers it seems appropriate that this Series as a whole should be dedicated to the fond memory which the Society holds of him. CONTENTS Foreword 1 I. The historical roots of an open society. 4 II. Social classes and the rise of Catalan industrial capitalism. 15 III. A broken progress. 28 IV. The structure and change of Catalan society, 1939-1980. 38 V. The reconquest of democracy. 54 VI. The future of the Catalans. 65 Appendices. Maps. 75 A Select Bibliography. 77 FOREWORD A la memòria de Josep Maria Sariola i Bosch, català com cal The following essay is based on a lecture given at a meeting of the Anglo- Catalan Society in November 1979* Members of the Society's Committee kindly suggested that I write up the ideas presented at that meeting so that they could be published under its auspices in a series of Occasional Papers then being planned. -

Vip Experiences in Barcelona

VIP EXPERIENCES IN BARCELONA 7 PM – 8.30 PM Exclusive guided visit to La Pedrera / Nov – Feb Transfer to la Pedrera on your own (Easily by taxi) La Pedrera is one of the best-known works of the architect Gaudí, and is one of the symbols of Barcelona. It was built between 1906 and 1912, and consists of a succession of stone walls on the outside, while the interior has two painted courtyards, columns and a range of rooms. There are large windows and iron balconies set into the undulating façade. On the roof, meanwhile, there are chimneys and sculptures which are works of art in themselves, as well as a splendid view of the Paseo de Gràcia Avenue. The building has been declared a World Heritage, and is the pinnacle of Modernist techniques and tendencies. Antoni Gaudí is one of the world’s most renowned architects, and a trip to Barcelona must include a visit of at least one of his famed modernist buildings, of which La Pedrera (or Casa Milà) is one of the most well-known and the second most visited museum in Barcelona. During the calm hours at sunset, this intimate and private tour will unveil to you the building's secrets not seen on daytime visits. See how residents lived in this beautiful building 100 years ago; visit several rooms; and enjoy outstanding views of La Sagrada Familia and the Barcelona skyline from the roof. Your after-hours tour of La Pedrera starts in the residential building in the Provenca street courtyard. Hear about the building’s most significant features and see a display of the elements that inspired Gaudí’s design. -

Barcelona Curious Guide by Hostal Mare Nostrum

Barcelona Curious Guide by Hostal Mare Nostrum Welcome to Barcelona! Hostal Mare Nostrum present you this handy guide of the city. The Barcelona Curious Guide has been developed by the staff of Hostal Mare Nostrum to inform and recommend to our guests, everything that they can find in our city. In the guide you can find all kinds of information about historical and architectural places around Barcelona. In addition we recommend some establishments and restaurants where you can enjoy the best mediterranean food. Hostal Mare Nostrum is located at the heart of Barcelona, 2 min walking from Liceu Metro Station and 5 min walking from Plaza Catalunya, where you can get many buses and find train connections to all points of Barcelona city, Catalonia and Spain, so all routes we suggest can start easily from our hostal. Choose your itinerary and discover Barcelona! DAY 1 – A walking tour through Gothic, Born, Raval and Barceloneta Quarters This tour is at walking distance. Recommended for your first day - to start exploring the city. • Las Ramblas Las Ramblas is the most lively and emblematic street in Barcelona and it is full of restaurants, Cafés, shops, bars, beautiful flower shops, human statues and painters. In Las Ramblas you will also find the famous Opera House Liceu, Canaletes Fountain (where Barça supporters meet and celebrate when FC Barcelona wins an important match), the Boqueria Market, the Wax Museum, the Erotic Museum, Palau Güell, Colombus Monument and the Royal Gothic Shipyards. <M> Catalunya L1, L3 <M> Liceu L3 <M> Drassanes L3 • La Boqueria Market “Boqueria Market” is a space full of life, history and architectural value. -

Art and Politics in 1900 Catalan Sculpture in Latin America 1 Drs

Strand 2. Art Nouveau and Politics in the Dawn of Globalisation Art and politics in 1900 Catalan Sculpture in Latin America 1 Drs. Cristina Rodríguez-Samaniego and Natàlia Esquinas Giménez Abstract This paper touches on the presence of modernista sculpture in Latin America around 1900 and its political implications. Art Nouveau coincides in time with an era of urban changes in American cities and it is also the age of national independence movements –or else their first anniversary-. The need for prestigious monumental sculptors and plaster copies was so high that it ought to be satisfied with foreign creators. The contribution of Catalan sculptors here is remarkable, and has not been thoroughly studied yet. Some Catalan sculptors stayed in America for long periods, while others travelled just for specific projects. In other cases, their works were purchased by museums or other public institutions. This paper focuses on case studies, located mainly in the Southern Cone, in order to contribute to the comprehension of the means by which modernista sculpture participates in the construction or consolidation of some American national discourses. Keywords: Sculpture, Art Nouveau, Catalan art in America, Monumental sculpture, Politics in Art 1 This paper is a result of the research project Entre ciudades: paisajes culturales, escenas e identidades (1888- 1929) , funded by Spain’s Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (HAR 2016-78745-P) lead by GRACMON group of research at the University of Barcelona. 1 One of our main fields of research in the past few years has been the presence of Catalan artists in Latin America, from the late-19 th to the early-20 th centuries. -

Press Pack 2019

Press Pack 2019 Index INTRODUCTION 4 COMMUNICATIONS NETWORK 6 CATALONIA, A QUALITY DESTINATION 10 TOURIST ATTRACTIONS 14 TOURIST ACCOMMODATION 18 TOURIST BRANDS 21 Costa Brava 22 Costa Barcelona 24 Barcelona 26 Costa Daurada 28 Terres de l’Ebre 30 Pirineus 32 Terres de Lleida 34 Val d’Aran 36 Paisajes Barcelona 38 TOURIST EXPERIENCES 40 Activities in Natural and Rural Areas 42 Accessible Catalonia 46 Sports and Golf Tourism 50 Wine Tourism 52 Gastronomy 54 Great Cultural Icons and Great Routes 56 Hiking and Cycling 58 Medical & Health Tourism 60 Premium 61 Business Tourism 62 Family Holidays 64 WHAT’S NEW 2019 66 USEFUL ADDRESSES 81 3 Introduction Catalonia is a Mediterranean destination with a millenary history, its own culture and language and a wealthy historical and natural heritage. POPULATION. 7.5 million SURFACE AREA. 32,107 km2 TERRITORY. Catalonia offers a great scenic variety: 580 kilometres of Mediterranean coastline cover Costa Brava, Costa Barcelona, Barcelona, Costa Daurada and Terres de l’Ebre The Catalan Pyrenees with their 3000 metre peaks dominate the northern area of the country. Especially interesting is Val d’Aran, a valley draining into the Atlantic Ocean that has preserved its own culture, language (Aranese) and government bodies. Both the capital of Catalonia, Barcelona, and the three province seats, Girona, Tarragona and Lleida, feature a great variety of sights. In the rest of Catalonia, numerous towns with a distinct character boast some noteworthy heritage: handsome old quarters, buildings from Romanesque to Art Nouveau and a wide range of museums are worth a visit. CLIMATE. Generally speaking, Catalonia enjoys a temperate and mild Mediterranean climate, characterised by dry, warm summers and moderately cool winters. -

Catalonia Is a Country: World Heritage

CATALONIA IS A COUNTRY: WORLD HERITAGE AND REGIONAL NATIONALISM by MATTHEW WORTH LANDERS A THESIS Presented to the Department ofGeography and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts March 2010 11 "Catalonia Is a Country: World Heritage and Regional Nationalism," a thesis prepared by Matthew Worth Landers in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master ofArts degree in the Department ofGeography. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Dr. Alexander B. Murphy, Chair ofthe Examining Committee Date Committee in Charge: Dr. Alexander B. Murphy, Chair Dr. Xiaobo Su Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School 111 © 2010 Matthew Worth Landers IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Matthew Worth Landers for the degree of Master ofArts in the Department ofGeography to be taken March 2010 Title: CATALONIA IS A COUNTRY: WORLD HERITAGE AND REGIONAL NATIONALISM Approved: Alexander B. Murphy Since 1975, the Spanish autonomous region ofCatalonia has been renegotiating its political and cultural place within Spain. The designation and promotion ofplaces within Catalonia as World Heritage Sites-a matter over which regional authorities have competency-provides insights into the national and territorial ideas that have emerged in recent decades. This study ofthe selection and portrayal ofWorld Heritage sites by Turisme de Cata1unya shows that the sites reflect a view ofthe region as 1) home to a distinct cultural group, 2) a place with an ancient past, and 3) a place with a history of territorial autonomy. These characteristics suggest that even though many Catalan regionalists seek a novel territorial status that is neither independent ofnor subservient to the Spanish state, the dominant territorial norms ofthe modem state system continue to be at the heart ofthe Catalan nation-building project. -

English Edition! English

OFFICIAL GUIDE OF BCN ENGLISH EDITION! ENGLISH GET READY FOR YOUR CLOSE-UP. COME FACE-TO-FACE WITH AMAZING ART ON THE CITY’S STREETS... 2 Buy tickets & book restaurants at www.timeout.com/barcelona & www.visitbarcelona.com Time Out Barcelona in English The Best February 2015 A meditating bull is just one of the fabulous artworks of BCN youoll Ɓnd on Barcelonaos streets p. 20 Features 14. Open-air art The streets of Barcelona are, sadly, not paved with gold, but, as Ricard Mas proves, they are full of 21st-century art... 20. All the city’s a canvas ...and a lot of not-so-recent artwork as well. María José Gómez takes us on a short tour. 22. What Barcelona wears Residents share their wardrobe choices as Hannah Pennell checks out local style. 26. A place to feel at home Cyclists, surfers and Lost fans. In BCN, Ricard Martín tells us, they all have their own bar. 28. Musicals masterclass Juan Carlos Olivares compares and contrasts MORENO IVÁN two of the biggest stage shows now on. Regulars 30. Shopping & Style 34. Things to Do 42. The Arts 54. Food & Drink 62. Clubs 64. LGBT 65. Getaways MORENO IVÁN MARIA DIAS Barcelona is full of fan bars – for aƁcionados of Meet three local designers showing their wares 66. BCN Top Ten rock, Seat 600s and Sara Montiel p. 26 at this month’s 080 Barcelona Fashion p. 30 Via Laietana, 20, 1a planta | 08003 Barcelona | T. 93 310 73 43 ([email protected]) Impressió LitograƁa Rosés Publisher Eduard Voltas | Finance manager Judit Sans | Business manager Mabel Mas | Editor-in-chief Andreu Gomila | Deputy editor Hannah Pennell | Features & web Distribució S.A.D.E.U. -

Notes on Dalí As Catalan Cultural Agent Carmen García De La Rasilla

You are accessing the Digital Archive of the Esteu accedint a l'Arxiu Digital del Catalan Catalan Review Journal. Review By accessing and/or using this Digital A l’ accedir i / o utilitzar aquest Arxiu Digital, Archive, you accept and agree to abide by vostè accepta i es compromet a complir els the Terms and Conditions of Use available at termes i condicions d'ús disponibles a http://www.nacs- http://www.nacs- catalanstudies.org/catalan_review.html catalanstudies.org/catalan_review.html Catalan Review is the premier international Catalan Review és la primera revista scholarly journal devoted to all aspects of internacional dedicada a tots els aspectes de la Catalan culture. By Catalan culture is cultura catalana. Per la cultura catalana s'entén understood all manifestations of intellectual totes les manifestacions de la vida intel lectual i and artistic life produced in the Catalan artística produïda en llengua catalana o en les language or in the geographical areas where zones geogràfiques on es parla català. Catalan Catalan is spoken. Catalan Review has been Review es publica des de 1986. in publication since 1986. Notes on Dalí as Catalan Cultural Agent Carmen García De La Rasilla Catalan Review, Vol. XIX, (2005), p. 131-154 NOTES ON DALÍ AS CATALAN CULTURAL AGENT CARMEN GARCÍA DE LA RASILLA ABSTRACT Was Salvador Dalí a legitimate and effective agent in the spread of Catalan cu!ture? This article approaches the artist's idiosyncratic, contentious and "politically incorrect" Catalanism and examines how he translated certain major Catalan cultural and philosophical components of his work into the cosmopolitan aesthetics of moderniry and surrealism. -

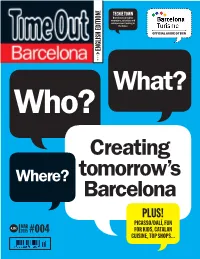

Creating Tomorrow's Barcelona

TECHIE TOWN Barcelona is a hub for innovators, scientists and entrepreneurs looking to the future OFFICIAL GUIDE OF BCN ENGLISH EDITION! ENGLISH What? Who? Creating Where? tomorrow’s Barcelona PLUS! PICASSO/DALÍ, FUN MAR 4,95€ 2015 #004 FOR KIDS, CATALAN CUISINE, TOP SHOPS... 2 Buy tickets & book restaurants at www.timeout.com/barcelona & www.visitbarcelona.com Time Out Barcelona in English The Best March 2015 If you’re in Barcelona on a family trip, we show you of BCN some of the best places to take your children p. 26 Features 14. Looking into the future Meet the people, projects and places at the heart of the city’s technological advances. 20. Fisticuffs! BCN saw a boxing boom in the Ɓrst half of the 20th century – Julià Guillamon gloves up. 24. Fried to perfection Laura Conde introduces us to the churro, Spanish cousin of the doughnut. 26. Young visitors Barcelona is full of places to keep kids happy – Jan Fleischer suggests a few of the best. 28. Compare and contrast Alx Phillips previews a new show exploring the parallel lives of Picasso and Dalí. CHASSEROT SCOTT Regulars 30. Shopping & Style 34. Things to Do 42. The Arts 54. Food & Drink 62. Clubs 64. LGBT IVAN GIMÉNEZ IVAN 65. Getaways PUKAS SURF BARCELONA Barcelona is a fantastic place for Ɓtness fans to Welcome to the wondrous world of the churro, 66. BCN Top Ten get out and about p. 34 the local version of the doughnut p. 24 Via Laietana, 20, 1a planta | 08003 Barcelona | T. 93 310 73 43 ([email protected]) Impressió LitograƁa Rosés Publisher Eduard Voltas | Finance manager Judit Sans | Business manager Mabel Mas | Editor-in-chief Andreu Gomila | Deputy editor Hannah Pennell | Features & web Distribució S.A.D.E.U. -

Modernisme and the 1888 Universal Exposition of Barcelona

HISTORICAL LAB 1 BRUXELLES-BRUSSELS, 22 OCTOBER 2005-12-19 BY LLUIS BOSCH PASCUAL, HISTORIAN, INSTITUT DE PAISATGE URBÀ I LA QUALITAT DE VIDA, AJUNTAMENT DE BARCELONA Modernisme and the 1888 Universal Exposition of Barcelona The time of birth of the Modernisme Movement’s is often a matter of debate. Some scholars (notably Alexandre Cirici) place it in the 1880-85 period, when emblematic Modernista buildings such as Gaudí’s Casa Vicens, Domènech i Estapà’s Academy of Sciences or Domènech i Montaner’s Editorial Montaner i Simon were completed. By contrast, a few others have refused to view early Modernisme as little more than inspired eclecticism, and delay the birth of Modernisme as a truly new style to the late 1890’s, when Catalan artists of all disciplines began to catch on to the influence of Belgian and Parisian Art Nouveau, and soon also of Viennese Secesion. However, nowadays there seems to be some sort of consensus in establishing the year 1888 as the moment in which Modernisme could be safely said to be more than a few peculiar and isolated works, and had become an artistic movement by its own right. Perhaps a suitable synthesis of these three hypotheses would be to say that Catalan Modernisme made its first steps in the early eighties and by 1888 had become the prolific and popular, albeit polemic movement that was to dominate the Catalan artistic scene for the next two decades, during which it would successively embrace Art Nouveau, Secesion and Jugendstil, importing ideas and solutions to blend them into the Catalan “inspired eclecticism” of early Modernisme. -

Yearbook 2017

Institut Ramon Llull Yearbook 2017 Institut Ramon Llull Yearbook 2017 Contents Introduction ........................................................... 5 Major Projects 2017 ............................................... 6 Ramon Llull Prizes 2017 ....................................... 12 Literature and the Humanities ............................ 14 Performing Arts ................................................... 22 Film ....................................................................... 34 Music ..................................................................... 42 Visual Arts, Architecture and Design ................. 50 Language and Universities ................................. 60 Press and Communications ................................ 74 Budget 2017 ......................................................... 80 Managing Board Manuel Forcano Director Josep Marcé General manager Marta Oliveres Head of the Department of Visual and Performing Arts Izaskun Arretxe Head of the Department of Literature Josep-Anton Fernàndez Head of the Department of Language and Universities Introduction In 2017, the Institut Ramon Llull carried on its task of promoting awareness abroad of the Catalan language and culture, in keeping with the aims of the established Plan of action. This involved a geographical focus on the Mediterranean area and some countries where the Institut Ramon Llull had not yet initiated activities of cultural diplomacy, among them South Africa, Tunisia, Lebanon, the United Arab Emirates and Ukraine. The cultural activities