Changes in Spanish Texas Main Ideas Key Terms and People 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spanish Return to Texas Main Ideas Key Terms and People 1

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=TX-A Section 3 The Spanish Return to Texas Main Ideas Key Terms and People 1. In response to a perceived threat from the French, the • Francisco Hidalgo Spanish resettled in East Texas in the early 1700s. • Louis Juchereau de 2. The Spanish built several missions, a presidio, and the St. Denis region's first civil settlement near what is now San Antonio. • Domingo Ramón • Antonio Margil de Jesús Why It Matters Today • Martín de Alarcón The Spanish tried to protect their hold on Texas by • El Camino Real barring foreign trade in the region. Use current events sources to learn more about free trade issues or a trade dispute between nations today. TEKS: 1B, 2C, 9A, 21A, 21B, 21C, 22D The Story Continues Father Francisco Hidalgo was a patient but persistent myNotebook man. Since becoming a Franciscan at the age of 15, he Use the annotation had longed to become a missionary, travel, and spread the Bleed Art Guide: tools in your eBook All bleeding art should be extended fullyto to takethe notes on the Catholic faith. After arriving in New Spain, the young priest bleed guide. return of Spanish missionaries and heard many stories about Texas. He became determined to settlers to Texas. go there to teach Texas Indians about Catholicism. Delay after delay prevented Father Hidalgo from reaching them. But he knew that his chance would come. Art and Non-Teaching Text Guide: Folios, annos, standards, non-bleeding art, etc. should Back to East Texas never go beyond this guide on any side, 1p6 to trim. -

Mission Santa Cruz De San Sabá Case Study

INSTRUCTOR GUIDE Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá Case Study TIME FRAME 2 class periods SPANISH COLONIZATION “The Destruction of Mission San Sabá in the Province of Texas and the Martyrdom of the Fathers Alonso de Terreros,” Joseph Santiesteban, 1765. SUMMARY Texas has a rich archeological record with deep connections to Spanish missions and presidios. One mission in particular, Santa Cruz de San Sabá, presents an interesting case TEKS (GRADES 4 & 7 study of mid- to late-Spanish colonization attempts and the strategies that archeologists use to investigate that evidence. Using primary and secondary documents, students will TEKS Social Studies: investigate what happened at Mission San Sabá on March 6, 1758, and reflect on current 4th Grade: 1(B), 2(A), archeological discoveries at that site. 2(C), 6(A), 12(A), 21 (A-E), 23(A-B) 7th Grade: 1(B), OBJECTIVE(S): VOCABULARY 2(C), 19(C), 21(A-G), • Analyze primary source documents, 23 (A-B) mission (MISH-uh n): A maps, artifact images, and recorded Spanish Colonial settlement for testimonials to build context around TEKS ELA: Christianizing the Native Americans Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá and 4th Grade: 10, 11(C), of a region; the settlement included 24(A), 25, 26, 29 the events which led to its demise. a mission church and Indian quarters. 7th Grade: 1(A-D), 5(E), 6(D), 6(G), • Demonstrate their understanding presidio (pruh-SID-ee-oh): 12 (D-H) of the evidence through The Spanish word for fort; the oral presentation. surviving Spanish forts in Texas are TEKS Science: 4th Grade: 2(B), 2(D) still called presidios GUIDING QUESTION 7th Grade: 7th: 2(E) • What were archeologists able to learn excavate (eks-kuh-VAYT): about the events which took place In archeology, to excavate means to at Mission Santa Cruz de San investigate a site through a careful, Sabá by examining primary and scientific digging process. -

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico Manuscripts New Spain Finding Aid Prepared by David M

New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts New Spain Finding aid prepared by David M. Szewczyk. Last updated on January 24, 2011. PACSCL 2010.12.20 New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Table of Contents Summary Information...................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History.........................................................................................................................................3 Scope and Contents.......................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information...........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... 9 - Page 2 - New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Summary Information Repository PACSCL Title New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts Call number New Spain Date [inclusive] 1519-1855 Extent 5.8 linear feet Language Spanish Cite as: [title and date of item], [Call-number], New Spain and Early Independent Mexico manuscripts, 1519-1855, Rosenbach Museum and Library. Biography/History Dr. Rosenbach and the Rosenbach Museum and Library During the first half of this century, Dr. Abraham S. W. Rosenbach reigned supreme as our nations greatest bookseller. -

Changes in Spanish Texas

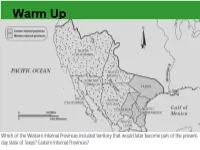

Warm Up The Mexican National Era Unit 5 Vocab •Immigrant - a person who comes to a country where they were not born in order to settle there •Petition - a formal message requesting something that is submitted to an authority •Tejano - a person of Mexican descent living in Texas •Militia - civilians trained as soldiers but not part of the regular army •Empresario -the Spanish word for a land agent whose job it was to bring in new settlers to an area •Anglo-American - people whose ancestors moved from one of many European countries to the United States and who now share a common culture and language •Recruit - to persuade someone to join a group •Filibuster - an adventurer who engages in private rebellious activity in a foreign country •Compromise - an agreement in which both sides give something up •Republic - a political system in which the supreme power lies in a body of citizens who can elect people to represent them •Neutral - Not belonging to one side or the other •Cede - to surrender by treaty or agreement •Land Title - legal document proving land ownership •Emigrate - leave one's country of residence for a new one Warm Up Warm-up • Why do you think that the Spanish colonists wanted to break away from Spain? 5 Unrest and Revolution Mexican Independence & Impact on Texas • Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla – Gave a speech called “Grito de Dolores” in 1810. Became known as the Father of the Mexican independence movement. • Leads rebellion but is killed in 1811. • Mexico does not win independence until 1821. Hidalgo’s Supporters Rebel Against Spain • A group of rebels led by Juan Bautista de las Casas overthrew the Spanish government in San Antonio. -

Spain's Texas Patriots ~ Its 1779-1,783 War with England During the American Revolution

P SPAIN'S TEXAS PATRIOTS ~ ITS 1779-1,783 WAR WITH ENGLAND DURING THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION PART 5 OF SPANISH BORDERLANDS STUDIES by Granville W. and N. C. Hough P ! i ! © Copyright 2000 1 by Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanea West, Apt B Lagtma Hills, CA 92653-2830 Email: [email protected] Other books in this series include: Spain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. Spain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the American Revolution, Part 2, 1999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the Amencan Revolution, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Published by: SHHAR PRESS Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research , P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655°0490 (714) 894-8161 Email: SHHARP~s~aol.com ;.'."/!';h',-:/.t!j.:'."-i ;., : [::.'4"!".': PREFACE o In 1996, the authors became aware that neither the NSDAR (National Society for the Daughters of the American Revolution) nor the NSSAR (National Society for the Sons of the American Revolution) would accept descendants of Spanish citi~e,qs of California who had contributed funds to defray expenses of the 1779-1783 war with England. As the patriots being turned down as suitable ancestors were also soldiers, the obvious question became: "Why base your membership application on a monetary contribution when the ancestor soldier had put.his life at stake?" This led to a study of how the Spani~a Army and Navy ~ad worked during the war to defeat the :~'. -

How Historical Myths Are Born ...And Why They Seldom

A depiction of La Salle's Texas settlement from Carlos Castañeda's Our Catholic Heritage in Texas (volume l) bearing the misnomer "Fort Saint Louis." How Historical Myths Are Born . And Why They Seldom Die* BY DONALD E. CHIPMAN AND ROBERT S. WEDDLE* Introduction HEN CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS MADE HIS FIRST LANDFALL ON the fringe of North America, he believed he had reached the WEast Indies. He therefore called the strange people he met "Indians," a name that came to be applied to all American indigenes. In similar manner, inappropriate names—or names misapplied—have risen all across the Americas. When one of these historical errors arises, it takes on a life of its own, though not without a healthy boost from us historians. Historians, of course, come in all stripes, and so do the myths they espouse. Somedmes the most egregious of them may result from the purest intentions. But there is no denying that others are born of impure motives, of which the most prevalent perhaps is chauvinism—bending his- tory out of shape by falsely linking some major historic episode to one's native province. Mostly, however, such miscues arise from the urgency to provide answers—an explanation, a name, or an opinion—before the facts at hand justify it. For example, consider the various identities posited for the river shown on the famous "Pineda" map sketch (ca. 1519) as El Rio del Espíritu Santo. Was it the Mississippi as it has been long thought to be, or some other stream, perhaps as far east as Florida or as far west as Texas? Still * Donald E. -

Spanish Relations with the Apache Nations East of the Rio Grande

SPANISH RELATIONS WITH THE APACHE NATIONS EAST OF THE RIO GRANDE Jeffrey D. Carlisle, B.S., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2001 APPROVED: Donald Chipman, Major Professor William Kamman, Committee Member Richard Lowe, Committee Member Marilyn Morris, Committee Member F. Todd Smith, Committee Member Andy Schoolmaster, Committee Member Richard Golden, Chair of the Department of History C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Carlisle, Jeffrey D., Spanish Relations with the Apache Nations East of the Río Grande. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May 2001, 391 pp., bibliography, 206 titles. This dissertation is a study of the Eastern Apache nations and their struggle to survive with their culture intact against numerous enemies intent on destroying them. It is a synthesis of published secondary and primary materials, supported with archival materials, primarily from the Béxar Archives. The Apaches living on the plains have suffered from a lack of a good comprehensive study, even though they played an important role in hindering Spanish expansion in the American Southwest. When the Spanish first encountered the Apaches they were living peacefully on the plains, although they occasionally raided nearby tribes. When the Spanish began settling in the Southwest they changed the dynamics of the region by introducing horses. The Apaches quickly adopted the animals into their culture and used them to dominate their neighbors. Apache power declined in the eighteenth century when their Caddoan enemies acquired guns from the French, and the powerful Comanches gained access to horses and began invading northern Apache territory. -

Hispanic Texans

texas historical commission Hispanic texans Journey from e mpire to Democracy a GuiDe for h eritaGe travelers Hispanic, spanisH, spanisH american, mexican, mexican american, mexicano, Latino, Chicano, tejano— all have been valid terms for Texans who traced their roots to the Iberian Peninsula or Mexico. In the last 50 years, cultural identity has become even more complicated. The arrival of Cubans in the early 1960s, Puerto Ricans in the 1970s, and Central Americans in the 1980s has made for increasing diversity of the state’s Hispanic, or Latino, population. However, the Mexican branch of the Hispanic family, combining Native, European, and African elements, has left the deepest imprint on the Lone Star State. The state’s name—pronounced Tay-hahs in Spanish— derives from the old Spanish spelling of a Caddo word for friend. Since the state was named Tejas by the Spaniards, it’s not surprising that many of its most important geographic features and locations also have Spanish names. Major Texas waterways from the Sabine River to the Rio Grande were named, or renamed, by Spanish explorers and Franciscan missionaries. Although the story of Texas stretches back millennia into prehistory, its history begins with the arrival of Spanish in the last 50 years, conquistadors in the early 16th cultural identity century. Cabeza de Vaca and his has become even companions in the 1520s and more complicated. 1530s were followed by the expeditions of Coronado and De Soto in the early 1540s. In 1598, Juan de Oñate, on his way to conquer the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, crossed the Rio Grande in the El Paso area. -

Bulletin 2 (8/86)

Dorothy Sloan Books – Bulletin 2 (8/86) 1. ABBOT, G. H. Mexico, and the United States; Their Mutual Relations and Common Interests. New York: Putnam, 1869. xvi, 391 pp., large folding colored map of Mexico, Texas, and the borderlands by Colton, another double-page map, steel-engraved portraits of Juárez and Romero. 8vo, original plum cloth, gilt seal of Mexican eagle on front cover. Slight discoloration to binding, else fine, map excellent. First edition. Larned 3925: “A useful guide to the constitutional history, especially for the period from 1824 to 1859.” Palau 521. $125.00 2. ADAMS, Ramon F. Come an’ Get It. The Story of the Old Cowboy Cook. Norman: Univ. Okla. Press [1952]. xii, 170 [1] pp., illustrations by Nick Eggenhofer. 8vo, original terracotta cloth, brown backstrip. Very fine in d.j. First edition. Adams, Herd 12: “The first and only book devoted to this unique and interesting character.” $35.00 3. ALAMAN, Lucas. Iniciativa de ley proponiendo al gobierno las medidas que se debian tomar para la seguridad del estado de Tejas y conservar la integridad del territorio mexicano de cuyo proyecto emanó la ley de 6 abril de 1830. Mexico: Vargas Rea, 1946. 50 pp. 8vo, original white printed wrappers. Very fine. First edition, limited edition (#16 of 100 copies). Alaman’s argument for one of the fundamental Texas laws, the Law of April 6, 1830, which banned U.S. immigration into Texas and, according to traditional Anglo interpretation, led to the Texas Revolution. See Streeter 759. $65.00 4. ALVARADO TEZOZOMOC, Hernando & Juan de Tovar. -

New Spain and the War for America, 1779-1783. Melvin Bruce Glascock Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1969 New Spain and the War for America, 1779-1783. Melvin Bruce Glascock Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Glascock, Melvin Bruce, "New Spain and the War for America, 1779-1783." (1969). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1590. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1590 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-237 GLASCOCK, Melvin Bruce, 1918- NEW SPAIN AND THE WAR FOR AMERICA, 1779-1783. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1969 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. New Spain and the War for America. 1779-1783 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Melvin Bruce Glascock B.S., Memphis State University, i960 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1964 May 1969 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to express his gratitude to Dr. John Preston Moore, Who directed this dissertation. -

Spanish Colonial Documents Pertaining to Mission Santa Cruz De San Saba (41MN23), Menard County, Texas

Volume 2007 Article 11 2007 Spanish Colonial Documents Pertaining to Mission Santa Cruz de San Saba (41MN23), Menard County, Texas Mariah F. Wade Jennifer K. McWilliams Texas Historical Commission, [email protected] Douglas K. Boyd [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Wade, Mariah F.; McWilliams, Jennifer K.; and Boyd, Douglas K. (2007) "Spanish Colonial Documents Pertaining to Mission Santa Cruz de San Saba (41MN23), Menard County, Texas," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2007, Article 11. https://doi.org/ 10.21112/ita.2007.1.11 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2007/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spanish Colonial Documents Pertaining to Mission Santa Cruz de San Saba (41MN23), Menard County, Texas Licensing Statement This is a work for hire produced for the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), which owns all rights, title, and interest in and to all data and other information developed for this project under its contract with the report producer. -

The University of Oklahoma Graduate College Spanish

THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SPANISH RELATIONS WITH THE INDIOS BARBAROS ON THE NORTHERN MOST FRONTIER OF NEW SPAIN IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ELIZABETH ANN HARPER JOHN N o rman, Ok1ahoma 1957 SPANISH RELATIONS WITH THE INDIOS BARBAROS ON THE NORTHERN MOST FRONTIER OF NEW SPAIN IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY APPROVED BY DISSERTATION COMMTTEE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author gratefully acknowledges her debt to Dr, Max L. Moorhead, whose scholarly perception and standards of excellence made his direction of this dissertation a genuine privilege for her. His generous cooperation greatly smoothed the difficulties attendant upon the completion of a degree in absentia. She wishes also to thank the dissertation committee for their helpful suggestions on the preparation of the fi nal draft. iii TABLE OP CONTENTS Page LIST OF îtîAPS ....................... V INTRODUCTION ......................................... 1 Chapter I. SPAIN MEETS THE INDIOS BARBAROS : RELATIONS WITH THE APACHES AND NAVAJOS TÔ 1715 .... 10 II. THE COMANCHES OVERTURN THE BALANCE OP POWER ON THE NORTHERN FRONTIER, 1700-1762 ......... 39 III. THE PROVINCIAS INTERNAS UNITE TO MEET THE THREAT OP THE BARBAROS. 1762-1786 ........... 98 IV. A SUCCESSFUL INDIAN POLICY EMERGES, 1786-1800 139 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................... 180 IV LIST OP MAPS Page Ranges of Indian Groups on the Spanish Frontier in the Eighteenth C e n t u r y ................. 12 The Northern Frontier of New Spa i n ................. 77 SPANISH RELATIONS WITH THE INDIOS BÂRBAROS ON THE NORTHERN FRONTIER OP NEW SPAIN IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY ' INTRODUCTION The subject of Spanish Indian policies is an extra ordinarily intricate one, as perhaps inevitably follows from the complex nature of the forces from which they emerged.