The Shadow in the Garden : Anden S Jungian Quests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 25

An Appeal for Expertise in Accountancy The Society would be very grateful to hear from any member living in the UK who has some knowledge of accountancy, and who would be willing to donate perhaps two hours of his or her time, once a year, in order to prepare a simple account of the Society's income and outgo. Ideally this would be someone living in or relatively near The London. If you fit this description, could you kindly get in touch with the Society at the postal address listed elsewhere on this page? W. H. Auden Society Memberships and Subscriptions Newsletter Annual memberships include a subscription to the Newsletter: Individual members £ 9 $15 ● Students £ 5 $8 Number 25 January 2005 Institutions £ 18 $30 New members of the Society and members wishing to renew should send sterling cheques or checks in US dollars payable to “The W. H. Auden Society” to Katherine Bucknell, 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW. Receipts available on request. Payment may also be made by credit card through the Society’s web site at: http://audensociety.org/membership.html The W. H. Auden Society is registered with the Charity Commission for England and Wales as Charity No. 1104496. Submissions to the Newsletter may be sent in care of Katherine Bucknell, 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW, or by e-mail to: [email protected] All writings by W. H. Auden in this issue are copyright 2005 by The Estate of W. H. Auden. 28 Foster’s recordings has been released in the Windyridge Variety series (www.musichallcds.com) and a brief excerpt may be heard at www.audensociety.org/vivianfoster.html on the Society’s website. -

Evolvong Wilds: Auden, Ecology, and the Formation of a New Poetics

EVOLVONG WILDS: AUDEN, ECOLOGY, AND THE FORMATION OF A NEW POETICS A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Jeremy Davis Jagger May 2020 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials i Thesis written by Jeremy Davis Jagger B.A., Malone University 2016 M.A., Kent State University, 2020 Approved by Dr. Tammy Clewell, PhD. , Advisor Dr. Robert Trogdon, PhD. , Chair, Department of English Dr. James Blank, PhD. , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………………...iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………………..iv CHAPTERS I. A Legacy in Crisis…………………………………………………………………….1 II. A Brief Note on Sacred Objects………………………………………………………6 III. Ecology in the Audenesque………………………………………………………….11 IV. Auden, Politics, and Hints of the Ecological………………………………………...26 V. America, Yeats, and a New Poetics………………………………………………….45 VI. A Reformed Poetics in Practice……………………………………………………...53 VII. When Nature and Culture Collide……………………………………………………72 VIII. A Legacy Cemented………………………………………………………………….86 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………………..89 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to thank Dr. Tammy Clewell for her many contributions to the production of this text. He would also like to acknowledge the contributions of his committee, Dr. Ryan Hediger and Dr. Babacar M’Baye. iv A Legacy in Crisis For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives In the valley of its making where executives Would never want to tamper, flows on south From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs, Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives, A way of happening, a mouth. —W.H. Auden, “In Memory of W.B. Yeat “The unacknowledged legislators of the world” describes the secret police, not the poets. -

Newsletter 32

The W. H. Auden Society Newsletter Number 32 ● July 2009 Memberships and Subscriptions Annual memberships include a subscription to the Newsletter: Contents Individual members £9 $15 Katherine Bucknell: Edward Upward (1903-2009) 5 Students £5 $8 Nicholas Jenkins: Institutions and paper copies £18 $30 Lost and Found . and Offered for Sale 14 Hugh Wright: W. H. Auden and the Grasshopper of 1955 16 New members of the Society and members wishing to renew should David Collard: either ( a) pay online with any currency by following the link at A New DVD in the G.P.O. Film Collection 18 http://audensociety.org/membership.html Recent and Forthcoming Books and Events 24 or ( b) use postal mail to send sterling (not dollar!) cheques payable to “The W. H. Auden Society” to Katherine Bucknell, Memberships and Subscriptions 26 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW, Receipts available on request. A Note to Members The W. H. Auden Society is registered with the Charity Commission for England and Wales as Charity No. 1104496. The Society’s membership fees no longer cover the costs of printing and mailing the Newsletter . The Newsletter will continue to appear, but The Newsletter is edited by Farnoosh Fathi. Submissions this number will be the last to be distributed on paper to all members. may be made by post to: The W. H. Auden Society, Future issues of the Newsletter will be posted in electronic form on the 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW; or by Society’s web site, and a password that gives access to the Newsletter e-mail to: [email protected] will be made available to members. -

Copyright by Jonathon N. Anderson 2019

Copyright by Jonathon N. Anderson 2019 GENRE AND AUDIENCE RECEPTION IN THE RAKE’S PROGRESS by Jonathon N. Anderson, BM THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The University of Houston-Clear Lake In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree MASTER OF ARTS in Literature THE UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON-CLEAR LAKE MAY, 2019 GENRE AND AUDIENCE RECEPTION IN THE RAKE’S PROGRESS by Jonathon N. Anderson APPROVED BY __________________________________________ David D. Day, J.D., Ph.D., Chair __________________________________________ Craig H. White, Ph.D., Committee Member RECEIVED/APPROVED BY THE COLLEGE OF HUMAN SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES: Samuel Gladden, Ph.D., Associate Dean __________________________________________ Rick J. Short, Ph.D., Dean Acknowledgements To Drs. White and Day, I offer my gratitude for your willingness to let me follow tangents and guesses throughout my graduate career. Dr. White, your generous indulgence, encouragement, and patient guidance helped me refine my fuzzy hunches to clearly articulated ideas. Dr. Day, your depth of knowledge on, enthusiasm for, and sense of humor with medieval works brings them to life and illuminates their continued relevance. I appreciate the priority both of you place on the excitement conjured by texts ancient and modern. To my parents, I offer my gratitude for maintaining a house strewn with interesting books waiting to be discovered. Mom, I appreciate all our late-night conversations about whatever random volume I happened to be curious about at the time. Dad, I hope I’m making good on the lifetime of blind confidence in my abilities you’ve given me. To Peg and Ed, the best in-laws anybody could ask for, thank you for your inspiration and advice. -

Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival 2008 Program

July 19 – September 19, 2014 World-class theatre. Right next door. Henry IV • The Merry Wives of Windsor • ShakeScenes • Much Ado About Nothing program_cover_art2014.indd 1 6/30/14 1:36 PM Laura & Jack B. Smith, Jr. are proud sponsors of NOTRE DAME SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL Giving Back to the Community TABLE OF CONTENTS 2–4 About Shakespeare at Notre Dame and the Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival 5 A Note from the Ryan Producing Artistic Director 6 Festival Events and Ticket Information 8–10 Welcome to the 2014 Season 12–15 Professional Company: HENRY IV 17–19 Young Company: THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR 21–22 ShakeScenes 25–26 Actors From The London Stage: MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING 29–39 Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival Cast and Company Profiles 40 Sponsors, Endowments, and Benefactors INSIDE BACK COVER Acknowledgments Festival Production Photographer — Peter Ringenberg LEFT: Robert Jenista, Tim Hanson, Ross Henry, and Kyle CENTER: Young Company Director West Hyler and RIGHT: Cheryl Turski instructs the Young Company in a Techentin work on the HENRY IV set. Stage Manager Nellie Petlick lead a rehearsal of THE movement class. MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR. SHAKESPEARE AT NOTRE DAME Dear Friends: Dear Friends: Here we are again: summer at Notre Welcome to the 2014 season of the Dame and that means the Notre Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival. It’s Dame Shakespeare Festival. a year of celebrations for all things Shakespeare here on campus. 2014 As always, there are the rich and var- marks not only Shakespeare’s 450th ied delights of local groups perform- birthday, but also the 150th anni- ing in ShakeScenes. -

First Name Initial Last Name

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Sarah E. Fass. An Analysis of the Holdings of W.H. Auden Monographs at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Rare Book Collection. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. April, 2006. 56 pages. Advisor: Charles B. McNamara This paper is an analysis of the monographic works by noted twentieth-century poet W.H. Auden held by the Rare Book Collection (RBC) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It includes a biographical sketch as well as information about a substantial gift of Auden materials made to the RBC by Robert P. Rushmore in 1998. The bulk of the paper is a bibliographical list that has been annotated with in-depth condition reports for all Auden monographs held by the RBC. The paper concludes with a detailed desiderata list and recommendations for the future development of the RBC’s Auden collection. Headings: Auden, W. H. (Wystan Hugh), 1907-1973 – Bibliography Special collections – Collection development University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Rare Book Collection. AN ANALYSIS OF THE HOLDINGS OF W.H. AUDEN MONOGRAPHS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL’S RARE BOOK COLLECTION by Sarah E. Fass A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. -

Prospero's Death: Modernism, Anti-Humanism and Un Re in Ascolto

Prospero’s Death: Modernism, Anti-humanism and Un re in ascolto1 But this rough magic I here abjure, and, when I have requir’d Some heavenly music, which even now I do, To work mine end upon their senses that This airy charm is for, I'll break my staff, Bury it certain fathoms in the earth, And deeper than did ever plummet sound I’ll drown my book. Solemn music. Prospero in William Shakespeare, The Tempest, V/1, 50-57 (Shakespeare 2004, p.67) Yet, at this very moment when we do at last see ourselves as we are, neither cosy nor playful, but swaying out on the ultimate wind-whipped cornice that overhangs the unabiding void – we have never stood anywhere else,– when our reasons are silenced by the heavy huge derision,–There is nothing to say. There never has been,–and our wills chuck in their hands– There is no way out. ‘Caliban to the Audience’, W. H. Auden, ‘The Sea and the Mirror’ (Auden 1991, p.444) Luciano Berio was riven by anxiety about opera and theatre. In an interview with Umberto Eco, ‘Eco in ascolto’, held in 1986 not long after the premiere of Un re in ascolto, he insists that the work should be considered a ‘musical action’ (azione musicale), a concept he associates with Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde and in which ‘musical process steers the story’. This he contrasts with opera, which, according to him, is ‘sustained by an “Aristotelian” type of narrative, which tends to take priority over musical development’ (Berio 1989, p.2). -

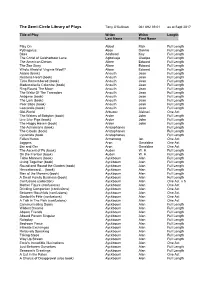

The Semi-Circle Library of Plays Tony O'sullivan 061 692 39 01 As at Sept 2017

The Semi-Circle Library of Plays Tony O'Sullivan 061 692 39 01 as at Sept 2017 Title of Play Writer Writer Length Last Name First Name . Play On Abbot Rick Full Length Pythagorus Abse Dannie Full Length Bites Adshead Kay Full Length The Christ of Coldharbour Lane Agboluaje Oladipo Full Length The American Dream Albee Edward Full Length The Zoo Story Albee Edward Full Length Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Albee Edward Full Length Ardele (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Restless Heart (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Time Remembered (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Mademoiselle Colombe (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Ring Round The Moon Anouilh Jean Full Length The Waltz Of The Toreadors Anouilh Jean Full Length Antigone (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length The Lark (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Poor Bitos (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Leocardia (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Old-World Arbuzov Aleksei One Act The Waters of Babylon (book) Arden John Full Length Live Like Pigs (book) Arden John Full Length The Happy Haven (book) Arden John Full Length The Acharnians (book) Aristophanes Full Length The Clouds (book) Aristophanes Full Length Lysistrata (book Aristophanes Full Length Fallen Heros Armstrong Ian One Act Joggers Aron Geraldine One Act Bar and Ger Aron Geraldine One Act The Ascent of F6 (book) Auden W. H. Full Length On the Frontier (book) Auden W. H. Full Length Table Manners (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Living Together (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Round and Round the Garden (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Henceforward... -

Tempest in Literary Perspective| Browning and Auden As Avenues Into Shakespeare's Last Romance

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1972 Tempest in literary perspective| Browning and Auden as avenues into Shakespeare's last romance Murdo William McRae The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation McRae, Murdo William, "Tempest in literary perspective| Browning and Auden as avenues into Shakespeare's last romance" (1972). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3846. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3846 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TEMPEST IN LITERAEY PERSPECTIVE: BRaWING AM) ADDER AS AVENUES INTO SHAKESPEARE'S LAST ROMANCE By Murdo William McRae B.A. University of Montana, 1969 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts TJNIVERSITT OF MONTANA • 1972 Approved by; IAIcxV^><L. y\ _L Chairman, Board ox Exarainers tats UMI Number EP34735 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT MUiMng UMI EP34735 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. -

23 Maritime Fantasies and Gender Space in Three

DOI: 10.2478/v10320-012-0026-5 MARITIME FANTASIES AND GENDER SPACE IN THREE SHAKESPEAREAN COMEDIES WAI FONG CHEANG Chang Gung University, Taiwan Wen-Hwa 1st Road, Kwei-Shan Tao-Yuan,Taiwan [email protected] Abstract: Laden with sea images, Shakespeare‘s plays dramatise the maritime fantasies of his time. This paper discusses the representation of maritime elements in Twelfth Night, The Tempest and The Merchant of Venice by relating them to gender and space issues. It focuses on Shakespeare‘s creation of maritime space as space of liberty for his female characters. Keywords: Shakespeare, maritime space, gender, Twelfth Night, The Tempest, The Merchant of Venice As a crucial constituent of the planet Earth, the sea has always had some influence on socio-cultural aspects of human life, especially for islanders surrounded by water. Great works of world literature, such as Homer‘s Iliad and Odyssey, manifest human beings‘ deep involvement with the vast expanse of water around their lands. Not unlike the Greeks, the English, as islanders, have a long history of involvement with the sea. The English Renaissance was a period during which real and imaginary ambitions beyond seas boomed, stimulating rich literary productions reflecting this cultural- historical reality. The huge fantasies of the English regarding sea adventures during the Renaissance were triggered by excitement arising from the discovery of new lands and trade routes and the legends of successful pirates. ―Chronicles of New World explorers,‖ such as updated Jamestown narratives, ―appeared regularly in London bookshops‖ and were read by ―an eager public‖ (Woodward 2009:5-9). -

PART 3 World War II and Its Aftermath

PART 3 World War II and Its Aftermath It’s a Long, Long Way, 1941. Henry Lamb. Oil on canvas. South African National Gallery, Cape Town. “What is absurd and monstrous about war is that men who have no personal quarrel should be trained to murder one another in cold blood.” —Aldous Huxley, “Words and Behavior” 1165 Henry Lamb/ South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa/Bridgeman Art Library 11165165 U6P3-845482.inddU6P3-845482.indd Sec2:1165Sec2:1165 11/29/07/29/07 1:57:121:57:12 PMPM BEFORE YOU READ Be Ye Men of Valor MEET WINSTON CHURCHILL “ lood, toil, tears, and sweat.” These unforget- Political Career Churchill’s military experience table words of Winston Churchill were not and his background as a writer gave him a unique Bmerely a rallying cry, but his approach to advantage in the political realm. He served in life. He is perhaps one of the most renowned prime numerous positions in Parliament, including home ministers of Great Britain, inspiring a nation and secretary, first lord of the Admiralty, minister of leading it to victory in the face of World War II. munitions, secretary of state for war and air, and secretary for the colonies. In 1940 Churchill became prime minister just as the Germans invaded Belgium—a post he held until the end of the war and “You ask, what is our aim? I can the defeat of the Axis powers. answer in one word: Victory—victory A Literary Knight At the age of seventy-one, at all costs, victory in spite of all Churchill was voted out of office as prime min ister, terror; victory, however long and hard but he was reelected six years later. -

The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden This volume brings together specially commissioned essays by some of the world’s leading experts on the life and work of W. H. Auden, one of the major English-speaking poets of the twentieth century. The volume’s contributors include a prize-winning poet, Auden’s literary executor and editor, and his most recent, widely acclaimed biographer. It offers fresh perspectives on his work from new and established Auden critics, alongside the views of specialists from such diverse fields as drama, ecological and travel studies. It provides scholars, students and general readers with a comprehensive and authoritative account of Auden’s life and works in clear and accessible English. Besides providing authoritative accounts of the key moments and dominant themes of his poetic development, the Companion examines his language, style and formal innovation, his prose and critical writing and his ideas about sexuality, religion, psychoanalysis, politics, landscape, ecology and globalisation. It also contains a comprehensive bibliography of writings about Auden. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO W. H. AUDEN EDITED BY STAN SMITH © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge