An Updated Strategic and Economic Case for the Thames Tideway Tunnel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater London Authority

Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London March 2009 Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London A report by Experian for the Greater London Authority March 2009 copyright Greater London Authority March 2009 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 978 1 84781 227 8 This publication is printed on recycled paper Experian - Business Strategies Cardinal Place 6th Floor 80 Victoria Street London SW1E 5JL T: +44 (0) 207 746 8255 F: +44 (0) 207 746 8277 This project was funded by the Greater London Authority and the London Development Agency. The views expressed in this report are those of Experian Business Strategies and do not necessarily represent those of the Greater London Authority or the London Development Agency. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................... 5 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... 5 CONSUMER EXPENDITURE PROJECTIONS .................................................................................... 6 CURRENT COMPARISON FLOORSPACE PROVISION ....................................................................... 9 RETAIL CENTRE TURNOVER........................................................................................................ 9 COMPARISON GOODS FLOORSPACE REQUIREMENTS -

The River Thames Phosphate Mode

HP NRA RIV NRA The River Thames Phosphate Mode/ Improvements on the River Colne model -* Investigation o f high decay rates -*■ Effects of phosphate stripping at STWs Gerrie Veldsink March 19% CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 THE NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY AND WATER QUALITY PLANNING 2 2.1 The National River Authority 2.2 The water Quality Planning Section in the Thames Region 3 3 THE RIVER THAMES PHOSPHATE MODEL 4 3.1 Introduction 5 3.2 TOMCAT 6 4 COLNE MODEL IMPROVEMENTS 8 4.1 River Colne 8 4.2 Modelling the River Colne 9 4.2.1 Introduction 9 4.2.2 Data input 10 4.2.2.1 Flow upstream of the STWs 10 4.2.2.2 Flow downstream of the bifurcation 11 4.2.2.3 The accretional flow 11 4.2.2.4 The concentration of phosphate in the accretional flow 11 4.2.2.5 Flow and quality of discharge from STWs 11 4.2.2.6 Flow and quality of the River Misbourne 11 4.2.2.7 Sources of data and important files 12 4.2.2.8 Differences between the original model and the model in this study 13 4.2.3 Calibration (OctobeLl992 to October 1994) 14 4.2.4 Validation (lanuary 1982 to lanuary 1984) 15 4.2.5 Sensitivity ofJheXolne Mode\ 16 4.3 Conclusion 1 7 5 WORK ON THE RIVER THAMES MODEL 18 5.1 Introduction 18 5.2 Order of STW 18 5.3 High Decay Rates 18 5.3.1 Introduction 18 5.3.2 Reducing high decay rates 19 5.3 Effects of phosphate stripping at STWs 23 5.4 Conclusion 24‘ REFERENCE 25 APPENDICES Acknowledgement ACKNOWLEDGEMENT With great pleasure I fulfilled a three month practical period at the NRA Thames Region in Reading. -

FOR SALE 331 KENNINGTON LANE, VAUXHALL, SE11 5QY the Location

COMMERCIAL PROPERTY CONSULTANT S 9 HOLYROOD STREET, LONDON, SE1 2EL T: 0207 939 9550 F: 0207 378 8773 [email protected] WWW.ALEXMARTIN.CO.UK PROPERTY PARTICULARS FOR SALE 331 KENNINGTON LANE, VAUXHALL, SE11 5QY The Location The property is situated in Kennington on the southern side of Kennington Lane (A3204) adjacent to the Lilian Baylis Technology School. The roperty is a short distance from Vauxhall Tube and British Rail Stations and also Vauxhall Bridge and the River Thames. The immediate environs are mixed use with educational, residential and retail. The open space of Spring Gardens, Vauxhall Farm, Vauxhall Park, Kennington Park and The Oval (Surrey County Cricket Club) are nearby. The property is located within the Vauxhall Conservation Area. FREEHOLD AVAILABLE (UNCONDITIONAL/ CONDITIONAL OFFERS INVITED) Description The property comprises a substantial mainly detached four storey and basement Victorian building last used for educational purposes by Five Bridges, a small independent school catering for 36 pupils. There are two parking spaces at the front, side pedestrian access and mainly paved rear yard with a substantial tree. The property is of typical construction for its age with solid built walls, pitched slate roofs, double hung single glazed sliding sash windows and timber suspended floors. The property benefits from central heating. COMMERCIAL PROPERTY CONSULTANT S 9 HOLYROOD STREET, LONDON, SE1 2EL T: 0207 939 9550 F: 0207 378 8773 [email protected] WWW.ALEXMARTIN.CO.UK PROPERTY PARTICULARS The accommodation comprises a net internal area of approximately: Floor Sq m Sq ft Basement 95 1,018 Ground 110 1,188 First 102 1,101 Second 100 1,074 Third 109 1,171 Total 516 5,552 The total gross internal area is 770 sq m (8,288 sq ft) The property is offered for sale freehold with vacant possession and offers are invited ‘Subject to Contract’ either on an ‘unconditional’ or ‘subject to planning’ basis General The property is located within Vauxhall Conservation Area (CA 32) and a flood zone as identified on the proposals map. -

192-198 Vauxhall Bridge Road , London Sw1v 1Dx

192-198 VAUXHALL BRIDGE ROAD , LONDON SW1V 1DX OFFICE TO RENT | 2,725 SQ FT | £45 PER SQ FT. VICTORIA'S EXPERT PROPERTY ADVISORS TUCKERMAN TUCKERMAN.CO.UK 1 CASTLE LANE, VICTORIA, LONDON SW1E 6DR T (0) 20 7222 5511 192-198 VAUXHALL BRIDGE ROAD , LONDON SW1V 1DX REFURBISHED OFFICE TO RENT DESCRIPTION AMENITIES The premises are located on the east side of Vauxhall Bridge Road, Comfort cooling between its junctions with Rochester Row and Francis Street. Excellent natural light Secondary glazing The area is well served by transport facilities with Victoria Mainline Perimeter trunking and Underground Stations (Victoria, Circle and District lines) being approximately 400 yards to the north. Suspended ceilings Fibre provision up to 100Mbs download & upload including There are excellent retail and restaurant facilitates in the secondary fallover connection surrounding area, particularly within Nova, Cardinal Place on Capped off services for kitchenette Victoria Street and also within the neighbouring streets of Belgravia. Lift Car parking (by separate arrangement) The plug and play accommodation is arranged over the third floor and is offered in an open plan refurbished condition. TERMS *Refurbished 1st floor shown, 3rd floor due to be refurbished. RENT RATES S/C Please follow this link to see a virtual walk through; £45 per sq ft. £16.92 per sq ft. £6.34 per sq ft. https://my.matterport.com/show/?m=MZvVtMCSkkz Flexible terms available. AVAILABILITY EPC Available upon request. FLOOR SIZE (SQ FT) AVAILABILITY WEBSITE Third Floor 2,725 Available http://www.tuckerman.co.uk/properties/active/192-198-vauxhall- TOTAL 2,725 bridge-road/ GET IN TOUCH WILLIAM DICKSON HARRIET DE FREITAS Tuckerman Tuckerman 020 3328 5374 020 3328 5380 [email protected] [email protected] SUBJECT TO CONTRACT. -

Rotherhithe to Canary Wharf Crossing - Meeting Note

Rotherhithe to Canary Wharf Crossing - Meeting Note Title: R2CW Port of London Authority Liaison Date 05-03-19 Timing: 14:00-16:00 Type: Meeting Location: PLA Offices, Pinnacle House, London EC3 Attendees: Nick Evans (NE) PLA (River Pilot) Stephen Milford TfL (Sponsor) Tom Chick (TC) TfL (Sponsor) Marinas (Various) Aim of the meeting: To update the London marinas on project progress since the last consultation and gain insight into potential concerns. Topics of discussion: Key topics of discussion were: i. Project Update; ii. Marina concerns No. Action Owner Deadline 1 TfL to provide information on the minimum height SM 31-03-2019 over the main span 2 TfL to meet/liaise with SKD and Limehouse SM 31-03-2019 marinas with regards to bridge operation generally, as well as potential of communication between marina lock and bridge bookings specifically 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Issued 14-09-18 Page 1 of 3 Rotherhithe to Canary Wharf Crossing - Meeting Note Key outcomes (dis/agreements, notable information shared) 1. Marinas concerned about vessels being unable to make bookings 2. Marinas appreciative of concept of ‘proactive bridge operator’ 3. PLA and Marinas like idea of communication between bridge and marina lock bookings 4. Marinas expect some form of accommodation for river users awaiting a lift such as mooring buoys Ref. Description Action 1.0 Introductions/Overview 1.1 NE outlined meeting agenda and gave a brief overview of planned river traffic in 2019 – the majority of commercial traffic will be due to Tideway Tunnel construction 2.0 PLA Updates 2.1 PLA/Marinas discussed licencing – all commercial vessels on the Thames must be licensced 2.2 PLA are currently reviewing the lighting arrangements for tugs 2.3 PLA gave information about the use of arches at Blackfriars Bridge: Arches 1 and 2 are currently closed for Tideway, with a ‘traffic light’ system currently on the navigational channel that sometimes requires recreational vessels to wait. -

Whose River? London and the Thames Estuary, 1960-2014* Vanessa Taylor Univ

This is a post-print version of an article which will appear The London Journal, 40(3) (2015), Special Issue: 'London's River? The Thames as a Contested Environmental Space'. Accepted 15 July 2015. Whose River? London and the Thames Estuary, 1960-2014* Vanessa Taylor Univ. of Greenwich, [email protected] I Introduction For the novelist A.P. Herbert in 1967 the problem with the Thames was simple. 'London River has so many mothers it doesn’t know what to do. ... What is needed is one wise, far- seeing grandmother.’1 Herbert had been campaigning for a barrage across the river to keep the tide out of the city, with little success. There were other, powerful claims on the river and numerous responsible agencies. And the Thames was not just ‘London River’: it runs for over 300 miles from Gloucestershire to the North Sea. The capital’s interdependent relationship with the Thames estuary highlights an important problem of governance. Rivers are complex, multi-functional entities that cut across land-based boundaries and create interdependencies between distant places. How do you govern a city that is connected by its river to other communities up and downstream? Who should decide what the river is for and how it should be managed? The River Thames provides a case study for exploring the challenges of governing a river in a context of changing political cultures. Many different stories could be told about the river, as a water source, drain, port, inland waterway, recreational amenity, riverside space, fishery, wildlife habitat or eco-system. -

Tidal Thames

1.0 Introduction The River Thames is probably the most recognised and best known river in the country and is often known as 'London's River' or 'Old Father Thames'. The River Thames was pivotal in the establishment of the city of London and people have lived along its banks for thousands of years. Today, over a fifth of the country’s population live within a few miles of it, and each day many thousands pass over, along and under it. The Thames is a transport route, a drain, a view, a site for redevelopment and, ever increasingly, a playground, classroom and wildlife corridor. Its habitats and species form an integral part of London’s identity and development. The tidal Thames of today is a good example of a recovering ecosystem and of great ecological importance not only to London, Kent and Essex but also to life in the North Sea and the upstream catchments of the upper Thames. Gravel foreshore, © Zoological Society of London The River Thames flows through Westminster with its high river embankments, overlooked by historic and modern buildings, crossed by seven bridges and overhung with hardy London Plane trees. In Westminster the river is tidal and exposes foreshore during low-tide over most of Tidal Thames this stretch. This foreshore is probably all that remains of the natural intertidal habitat that would have once extended The River Thames is probably the most recognised and best known river in the country and inland providing marsh and wetland areas. Within the Westminster tidal Thames plants, invertebrates and birds is often known as 'London's River' or 'Old Father Thames'. -

369 Kennington Lane, Vauxhall, SE11 5QY OFFICE to LET | HEART of VAUXHALL | READY for OCCUPATION to LET Area: 831 FT² (77M²) | Initial Rent: £38,000 PA |

369 Kennington Lane, Vauxhall, SE11 5QY OFFICE TO LET | HEART OF VAUXHALL | READY FOR OCCUPATION TO LET Area: 831 FT² (77M²) | Initial Rent: £38,000 PA | Location Tube Parking Availability Vauxhall Vauxhall 2 spaces available Immediate LOCATION: Situated just south of Central London, 369 Kennington Lane is a highly prominent office building positioned at the junction of Kennington Lane and Harleyford Road. Excellent transport connections via Vauxhall Station (Mainline and Victoria Line) providing easy and direct links into Central London. The area is similarly well connected to local bus routes. The A3 Kennington Park Road is easily accessed to the South East and to the West, Vauxhall Bridge provides access north of the River Thames, through to Victoria and to the West End. The popular residential and commercial area offers a wide range of cafés, bars and restaurants including; Pret A Manger, Starbucks Coffee, Dirty Burger along with a number of local independent retailers. Cont’d MISREPRESENTATION ACT, 1967. Houston Lawrence for themselves and for the Lessors, Vendors or Assignors of this property whose agents they are, give notice that: These particulars do not form any part of any offer or contract: the statements contained therein are issued without responsibility on the part of the firm or their clients and therefore are not to be relied upon as statements or representations of fact: any intending tenant or purchaser must satisfy himself as to the correctness of each of the statements made herein: and the vendor, lessor or assignor does not make or give, and neither the firm or any of their employees have any authority to make or give, any representation or warranty whatever in relation to this property. -

Thames Path Walk Section 2 North Bank Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge

Thames Path Walk With the Thames on the right, set off along the Chelsea Embankment past Section 2 north bank the plaque to Victorian engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette, who also created the Victoria and Albert Embankments. His plan reclaimed land from the Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge river to accommodate a new road with sewers beneath - until then, sewage had drained straight into the Thames and disease was rife in the city. Carry on past the junction with Royal Hospital Road, to peek into the walled garden of the Chelsea Physic Garden. Version 1 : March 2011 The Chelsea Physic Garden was founded by the Worshipful Society of Start: Albert Bridge (TQ274776) Apothecaries in 1673 to promote the study of botany in relation to medicine, Station: Clippers from Cadogan Pier or bus known at the time as the "psychic" or healing arts. As the second-oldest stops along Chelsea Embankment botanic garden in England, it still fulfils its traditional function of scientific research and plant conservation and undertakes ‘to educate and inform’. Finish: Tower Bridge (TQ336801) Station: Clippers (St Katharine’s Pier), many bus stops, or Tower Hill or Tower Gateway tube Carry on along the embankment passed gracious riverside dwellings that line the route to reach Sir Christopher Wren’s magnificent Royal Hospital Distance: 6 miles (9.5 km) Chelsea with its famous Chelsea Pensioners in their red uniforms. Introduction: Discover central London’s most famous sights along this stretch of the River Thames. The Houses of Parliament, St Paul’s The Royal Hospital Chelsea was founded in 1682 by King Charles II for the Cathedral, Tate Modern and the Tower of London, the Thames Path links 'succour and relief of veterans broken by age and war'. -

Upper Tideway (PDF)

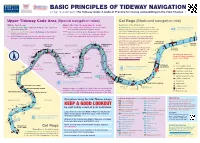

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF TIDEWAY NAVIGATION A chart to accompany The Tideway Code: A Code of Practice for rowing and paddling on the Tidal Thames > Upper Tideway Code Area (Special navigation rules) Col Regs (Starboard navigation rule) With the tidal stream: Against either tidal stream (working the slacks): Regardless of the tidal stream: PEED S Z H O G N ABOVE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE Outbound or Inbound stay as close to the I Outbound on the EBB – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Use the Inshore Zone staying as close to the bank E H H High Speed for CoC vessels only E I G N Starboard (right-hand/bow side) bank as is safe and H (right-hand/bow) side as is safe and inside any navigation buoys O All other vessels 12 knot limit HS Z S P D E Inbound on the FLOOD – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Only cross the river at the designated Crossing Zones out of the Fairway where possible. Go inside/under E piers where water levels allow and it is safe to do so (right-hand/bow) side Or at a Local Crossing if you are returning to a boat In the Fairway, do not stop in a Crossing Zone. Only boats house on the opposite bank to the Inshore Zone All small boats must inform London VTS if they waiting to cross the Fairway should stop near a crossing Chelsea are afloat below Wandsworth Bridge after dark reach CADOGAN (Hammersmith All small boats are advised to inform London PIER Crossings) BATTERSEA DOVE W AY F A I R LTU PIER VTS before navigating below Wandsworth SON ROAD BRIDGE CHELSEA FSC HAMMERSMITH KEW ‘STONE’ AKN Bridge during daylight hours BATTERSEA -

Thames Tideway Tunnel

www.WaterProjectsOnline.com Wastewater Treatment & Sewerage Thames Tideway Tunnel - Central Contract technical, logistical and operational challenges have required an innovative approach to building the Super Sewer close to some of London’s biggest landmarks by Matt Jones hames Tideway Tunnel is the largest water infrastructure project currently under construction in the UK and will modernise London’s major sewerage system, the backbone of which dates back to Victorian times. Although Tthe sewers built in the mid-19th century are still in excellent structural condition, their hydraulic capacity was designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette for a population and associated development of 4 million people. Continued development and population growth has resulted in the capacities of the sewer system being exceeded, so that when it rains there are combined sewer overflows (CSO) to the tidal Thames performing as planned by Bazalgette. To reduce river pollution, risk to users of the river and meet bespoke dissolved oxygen standards to protect marine wildlife, discharges from these combined sewer overflows (CSOs) must be reduced. The Environment Agency has determined that building the Tideway Tunnel in combination with the already completed Lee Tunnel and improvements at five sewage treatment works would suitably control discharges, enabling compliance with the European Union’s Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive. Visualisation showing cross section through the Thames Tideway Tunnel Central Victoria CSO site – Courtesy of Tideway Project structure and programme There is also a fourth overarching systems integrator contract The Thames Tideway Tunnel closely follows the route of the river, providing the project’s monitoring and control system. Jacobs intercepting targeted CSOs that currently discharge 18Mm3 of Engineering is the overall programme manager for Tideway. -

Rotherhithe Tunnel

Rotherhithe Tunnel - Deformation Monitoring CLIENT: TFL/ TIDEWAY EAST / SIXENSE Senceive and Sixense worked together to design and implement a monitoring programme to safeguard crucial London road tunnel during construction of a nearby tunnel shaft Challenge Solution Outcome The Thames Tideway Tunnel will capture, store and move Monitoring experts at Sixense chose the Senceive FlatMesh™ Senceive provided a fully wireless and flexible monitoring almost all the untreated sewage and rainwater discharges wireless system as their monitoring solution. A total of system which could be installed quickly and easily within that currently overflow into the River Thames in central 74 high precision tilt sensor nodes were installed during the short night-time closures. The installed system was London. The Rotherhithe Tunnel sits in close proximity engineering closures over an eight-week period to monitor sufficiently robust to operate for years without maintenance to the Tideway East shaft site and there was a need to any convergence/divergence during the works. - therefore avoiding the disruption, cost and potential risks ensure that the construction work did not threaten the associated with repeated site visits. Impact on the structure integrity of the tunnel. The CVB consortium (Costain, VINCI Of these, 64 were installed directly onto the tunnel lining in and damage to the tiles was minimal as the nodes required Construction Grands Projets and Bachy Soletanche), along 16 arrays of four nodes. A further 10 nodes were mounted on just a single mounting point and minimal cabling. with Sixense as their appointed monitoring contractor, three-metre beams in a vertical shaft. The FlatMesh™ system required a monitoring system in place 12 months ahead allowed all the nodes to communicate with each other and The Senceive and Sixense teams worked together to modify of shaft construction to provide an adequate period measure sub-mm movements for an estimated project tiltmeter fixings in order to incorporate a 3D prism needed of baseline monitoring.