Talk Here: a Personal Chronology in Linked Essays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crested Butte News

NEWS | COMMUNITY | SPORTS | CULTURE | OPINION Crested Butte News the News never sleeps | www.crestedbuttenews.com VOL.60 | NO.29 | JULY 17, 2020 | 50¢ New Gatesco affordable housing project ready to roll Gary Gates excited for 77-unit operative, so we don’t have any obstacles. It is development nice to get this going.” Located across from the Gunnison Recrea- [ BY MARK REAMAN ] tion Center near Walmart, the approximately $15 million project will have almost 90 percent The basic infrastructure is in. Large ma- of the units under a deed restriction. The units chinery is moving dirt across from the Gun- range from 375-square-foot efficiency units to nison Recreation Center with the intent to 1,268-square-foot single-family homes with see scores of affordable rental housing units three bedrooms and two bathrooms. There pop out of the ground within the next sever- will be everything from tri-plexes, to buildings al months for local workers. Foundations are with 16 units, to detached single-family homes. expected to be poured this week and framing There is a LIHTC (Low Income Housing to begin next week on the county’s latest af- Tax Credits) project going up in Gunnison so fordable housing project. The developer of the the idea is to fashion most of the Paintbrush 77-unit complex, tentatively called Paintbrush, units toward what might be considered mid- hopes to be renting the spaces by February dle-income workers making between $17 and 2021. $22 per hour. Twenty-nine units are meant to be Developer Gary Gates of Gatesco Inc. -

Discography of the Mainstream Label

Discography of the Mainstream Label Mainstream was founded in 1964 by Bob Shad, and in its early history reissued material from Commodore Records and Time Records in addition to some new jazz material. The label released Big Brother & the Holding Company's first material in 1967, as well as The Amboy Dukes' first albums, whose guitarist, Ted Nugent, would become a successful solo artist in the 1970s. Shad died in 1985, and his daughter, Tamara Shad, licensed its back catalogue for reissues. In 1991 it was resurrected in order to reissue much of its holdings on compact disc, and in 1993, it was purchased by Sony subsidiary Legacy Records. 56000/6000 Series 56000 mono, S 6000 stereo - The Commodore Recordings 1939, 1944 - Billy Holiday [1964] Strange Fruit/She’s Funny That Way/Fine and Mellow/Embraceable You/I’ll Get By//Lover Come Back to Me/I Cover the Waterfront/Yesterdays/I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues/I’ll Be Seeing You 56001 mono, S 6001 stereo - Begin the Beguine - Eddie Heywood [1964] Begin the Beguine/Downtown Cafe Boogie/I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me/Carry Me Back to Old Virginny/Uptown Cafe Boogie/Love Me Or Leave Me/Lover Man/Save Your Sorrow 56002 mono, S 6002 stereo - Influence of Five - Hawkins, Young & Others [1964] Smack/My Ideal/Indiana/These Foolish Things/Memories Of You/I Got Rhythm/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/Stardust/Sittin' In/Just A Riff 56003 mono, S 6003 stereo - Dixieland-New Orleans - Teagarden, Davison & Others [1964] That’s A- Plenty/Panama/Ugly Chile/Riverboat Shuffle/Royal Garden Blues/Clarinet -

Produced Byray Manzarek

PRODUCED BY RAY MANZAREK Originally released April 1980 Originally released May 1981 Originally released July 1982 Originally released September 1983 Frank Gargani Debbie Leavitt Power... Passion... Poetry! Attack the world. Let’s do some damage. What a band. Four monsters of skin. My favorite rockers of the then time. John Doe - Mr. Handsome - of the deep rich voice, the hard, strong jaw, the angular bass stance and the hot/cool lyrics. Their harmonies - some would say Schoenberg - his partner Exene, of the wailing scream in the night, the clear eyed pinning of American failings, the fine words of Diana Bonebrake love and booze and madness in the midnight dawn of Los Angeles. “Johny Hit and Run Paulene...” and he’s got a sterilized hypo filled with a sex-machine drug, and he only has 24 hours to shoot all Paulenes between the legs. So get busy, boy. And he does. Listen to those words! That naughty, naughty Johny. I love ‘em. And Exene’s “The World’s a Mess, it’s in My Kiss.” I just love that crazy combination: World - Mess - Kiss. And Billy Zoom on guitar, or is that at least 3 or 4 guitars. How does he do it? It’s so massive, so sharp, so bright, so fucking LOUD!!! And he is so silver smooth and cool. Effortless fingering, impeccable on the frets. Doesn’t he ever make a mistake? Is he a flesh and blood Valhalla guitar god? Yeahhh! And who is that madman beating the living shit out those drums? Ladies and Gentleman... D. -

![[Studycrux.Com] Golden in Death](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7387/studycrux-com-golden-in-death-217387.webp)

[Studycrux.Com] Golden in Death

Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this St. Martin’s Press ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com Time shall unfold what plaited cunning hides: Who cover faults, at last shame them derides. —William Shakespeare ’Tis education forms the common mind; Just as the twig is bent the tree’s inclined. —Alexander Pope Downloaded from https://www.studycrux.com 1 Dr. Kent Abner began the day of his death comfortable and content. Following the habit of his day off, he kissed his husband of thirty-seven years off to work, then settled down in his robe with another cup of coffee, a crossword challenge on his PPC, and Mozart’s The Magic Flute on his entertainment unit. His plans for later included a run through Hudson River Park, as April 2061 proved balmy and blooming. -

The Late Registrations and Corrections to Greene County Birth Records

Index for Late Registrations and Corrections to Birth Records held at the Greene County Records Center and Archives The late registrations and corrections to Greene County birth records currently held at the Greene County Records Center and Archives were recorded between 1940 and 1991, and include births as early as 1862 and as late as 1989. These records represent the effort of county government to correct the problem of births that had either not been recorded or were not recorded correctly. Often times the applicant needed proof of birth to obtain employment, join the military, or draw on social security benefits. An index of the currently available microfilmed records was prepared in 1989, and some years later, a supplemental index of additional records held by Greene County was prepared. In 2011, several boxes of Probate Court documents containing original applications and backup evidence in support of the late registrations and corrections to the birth records were sorted and processed for archival storage. This new index includes and integrates all the bound and unbound volumes of late registrations and corrections of birth records, and the boxes of additional documents held in the Greene County Archives. The index allows researchers to view a list arranged in alphabetical order by the applicant’s last name. It shows where the official record is (volume and page number) and if there is backup evidence on file (box and file number). A separate listing is arranged alphabetically by mother’s maiden name so that researchers can locate relatives of female relations. Following are listed some of the reasons why researchers should look at the Late Registrations and Corrections to Birth Records: 1. -

Here Is a Printable

Ryan Leach is a skateboarder who grew up in Los Angeles and Ventura County. Like Belinda Carlisle and Lorna Doom, he graduated from Newbury Park High School. With Mor Fleisher-Leach he runs Spacecase Records. Leach’s interviews are available at Bored Out (http://boredout305.tumblr.com/). Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. An Oral History of The Gun Club originally appeared in Razorcake #29, released in December 2005/January 2006. Original artwork and layout by Todd Taylor. Photos by Edward Colver, Gary Leonard and Romi Mori. Cover photo by Edward Colver. Zine design by Marcos Siref. Printing courtesy of Razorcake Press, Razorcake.org he Gun Club is one of Los Angeles’s greatest bands. Lead singer, guitarist, and figurehead Jeffrey Lee Pierce fits in easily with Tthe genius songwriting of Arthur Lee (Love), Chris Hillman (Byrds), and John Doe and Exene (X). Unfortunately, neither he nor his band achieved the notoriety of his fellow luminary Angelinos. From 1979 to 1996, Jeffrey manned the Gun Club ship through thick and mostly thin. Understandably, the initial Fire of Love and Miami lineup of Ward Dotson (guitar), Rob Ritter (bass), Jeffrey Lee Pierce (vocals/ guitar) and Terry Graham (drums) remains the most beloved; setting the spooky, blues-punk template for future Gun Club releases. At the time of its release, Fire of Love was heralded by East Coast critics as one of the best albums of 1981. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Assistance Series HAROLD M. JONES Interviewed by: Self Initial interview date: n/a Copyright 2002 ADST Dedicated with love and affection to my family, especially to Loretta, my lovable supporting and charming wife ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The inaccuracies in this book might have been enormous without the response of a great number of people I contacted by phone to help with the recall of events, places, and people written about. To all of them I am indebted. Since we did not keep a diary of anything that resembled organized notes of the many happenings, many of our friends responded with vivid memories. I have written about people who have come into our lives and stayed for years or simply for a single visit. More specifically, Carol, our third oldest daughter and now a resident of Boulder, Colorado contributed greatly to the effort with her newly acquired editing skills. The other girls showed varying degrees of interest, and generally endorsed the effort as a good idea but could hardly find time to respond to my request for a statement about their feelings or impressions when they returned to the USA to attend college, seek employment and to live. There is no one I am so indebted to as Karen St. Rossi, a friend of the daughters and whose family we met in Kenya. Thanks to Estrellita, one of our twins, for suggesting that I link up with Karen. “Do you use your computer spelling capacity? And do you know the rule of i before e except after c?” Karen asked after completing the first lot given her for editing. -

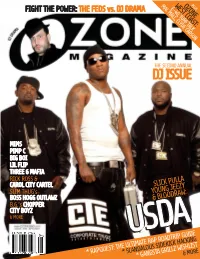

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

FEATURE PRESENTATION • G1 PRIX DE DIANE Contest

Visit the WIN WILLY DQ’d from TDN Website: GIII Razorback H. win www.thoroughbreddailynews.com P4 THURSDAY, JUNE 10, 2010 For information about TDN, call 732-747-8060. RACHEL ALEXANDRA TO FLEUR DE LIS Co-owner Jess Jackson announced yesterday that Horse of the Year Rachel Alexandra (Medaglia d=Oro) will make her next start in the GII Fleur de Lis S. Saturday at Churchill Downs. AAs long as she continues to progress, Peslier on Makfi... we intend to race her with the expecta- Olivier Peslier has been booked to partner the tion that she will obtain her fitness level G1 2000 Guineas winner Makfi (GB) (Dubawi {Ire}) in of last year, Jackson said in a state- @ Tuesday=s G1 St James=s Palace S., for which 15 were ment. AOur ultimate goal and hope is to declared yesterday. With Christophe-Patrice Lemaire enter the Breeders= Cup in November.@ retained by His Highness The Aga Sarah K Andrew photo Perfect in eight starts with three Grade I Khan for J “TDN Rising Star” wins against the boys during her cham- J Siyouni (Fr) (Pivotal {GB}), the pionship campaign, four-year-old Rachel Alexandra has Newmarket Classic winner=s own- been second in both starts this season, the Mar. 13 ers Mathieu Offenstadt, Alain New Orleans Ladies S. and the Apr. 30 GII La Troienne Louis-Dreyfus, Sylvain Fargeon S. The bay has been first or second in 15 of 16 appear- and Mikel Delzangles, who also ances, earning $3,074,050. Field, p3 trains the colt, have been forced to seek a new rider in the mile FEATURE PRESENTATION • G1 PRIX DE DIANE contest. -

John Marks Exits Spotify SIGN up HERE (FREE!)

April 2, 2021 The MusicRow Weekly Friday, April 2, 2021 John Marks Exits Spotify SIGN UP HERE (FREE!) If you were forwarded this newsletter and would like to receive it, sign up here. THIS WEEK’S HEADLINES John Marks Exits Spotify Scotty McCreery Signs With UMPG Nashville Brian Kelley Partners With Warner Music Nashville For Solo Music River House Artists/Sony Music Nashville Sign Georgia Webster Sony Music Publishing Renews With Tom Douglas John Marks has left his position as Global Director of Country Music at Spotify, effective March 31, 2021. Date Set For 64th Annual Grammy Awards Marks joined Spotify in 2015, as one of only two Nashville Spotify employees covering the country market. While at the company, Marks was instrumental in growing the music streaming platform’s Hot Country Styles Haury Signs With brand, championing new artists, and establishing Spotify’s footprint in Warner Chappell Music Nashville. He was an integral figure in building Spotify’s reputation as a Nashville global symbol for music consumption and discovery and a driver of country music culture; culminating 6 million followers and 5 billion Round Hill Inks Agreement streams as of 4th Quarter 2020. With Zach Crowell, Establishes Joint Venture Marks spent most of his career in programming and operations in With Tape Room terrestrial radio. He moved to Nashville in 2010 to work at SiriusXM, where he became Head of Country Music Programming. During his 5- Carrie Underwood Deepens year tenure at SiriusXM, he brought The Highway to prominence, helping Her Musical Legacy With ‘My to bring artists like Florida Georgia Line, Old Dominion, Kelsea Ballerini, Chase Rice, and Russell Dickerson to a national audience. -

Central Reformed Church Sixth Sunday of Easter May 17, 2020

Central Reformed Church Sixth Sunday of Easter May 17, 2020 REFLECTION “The following reasons may be given why children ought to love Jesus Christ above things in the world: He is more lovely in Himself. He is one that is greater and higher than all the kings of the earth, has more honor and majesty than they, and yet He is innately good and full of mercy and love. There is no love so great and so wonderful as that which is in the heart of Christ. He is one that delights in mercy. He is ready to pity those that are in suffering and sorrowful circumstances as one that delights in the happiness of His crea- tures. The love and grace that Christ has manifested does as much exceed all that which is in this world as the sun is brighter than a candle. Parents are often full of kindness towards their children, but that is no kindness like Jesus Christ’s…. There is more good to be enjoyed in Him than in everything or all things in this world. He is not only an amiable, but an all-sufficient good. There is enough in Him to answer all our wants and satisfy all our desires.” —Jonathan Edwards, “Children Ought to Love the Lord Jesus Christ Above All,” Sermons and Dis- courses: 1739-1742, in The Works of Jonathan Edwards, vol. 22, ed. Harry S. Stout (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 171-172. ORDER OF WORSHIP SIXTH SUNDAY OF EASTER MAY 17, 2020 9:30 am (We invite you to quiet your homes as you prepare for worship.) ____________________________________________________________ GATHERING IN LOVE Prelude “Moonlight Sonata, 1st Movement, Op. -

Taj Mahal Andyt & Nick Nixon Nikki Hill Selwyn Birchwood

Taj Mahal Andy T & Nick Nixon Nikki Hill Selwyn Birchwood JOE BONAMASSA & DAVE & PHIL ALVIN NUMBER FIVE www.bluesmusicmagazine.com US $7.99 Canada $9.99 UK £6.99 Australia A$15.95 COVER PHOTOGRAPHY © ART TIPALDI NUMBER FIVE 6 KEB’ MO’ Keeping It Simple 5 RIFFS & GROOVES by Art Tipaldi From The Editor-In-Chief 24 DELTA JOURNEYS 11 TAJ MAHAL “Jukin’” American Maestro by Phil Reser 26 AROUND THE WORLD “ALife In The Music” 14 NIKKI HILL 28 Q&A with Joe Bonamassa A Knockout Performer 30 Q&A with Dave Alvin & Phil Alvin by Tom Hyslop 32 BLUES ALIVE! Sonny Landreth / Tommy Castro 17 ANDY T & NICK NIXON Dennis Gruenling with Doug Deming Unlikely Partners Thorbjørn Risager / Lazy Lester by Michael Kinsman 37 SAMPLER 5 20 SELWYN BIRCHWOOD 38 REVIEWS StuffOfGreatness New Releases / Novel Reads by Tim Parsons 64 IN THE NEWS ANDREA LUCERO courtesy of courtesy LUCERO ANDREA FIRE MEDIA SHORE © PHOTOGRAPHY PHONE TOLL-FREE 866-702-7778 E-MAIL [email protected] WEB bluesmusicmagazine.com PUBLISHER: MojoWax Media, Inc. “Leave your ego, play the music, PRESIDENT: Jack Sullivan love the people.” – Luther Allison EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Art Tipaldi CUSTOMER SERVICE: Kyle Morris Last May, I attended the Blues Music Awards for the twentieth time. I began attending the GRAPHIC DESIGN: Andrew Miller W.C.Handy Awards in 1994 and attended through 2003. I missed 2004 to celebrate my dad’s 80th birthday and have now attended 2005 through 2014. I’ve seen it grow from its CONTRIBUTING EDITORS David Barrett / Michael Cote / Thomas J. Cullen III days in the Orpheum Theater to its present location which turns the Convention Center Bill Dahl / Hal Horowitz / Tom Hyslop into a dazzling juke joint setting.