Nine Constructions of the Crossover Between Western Art and Popular Musics (1995-2005)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

Bob James and Nancy Stagnitta "In the Chapel in the Moonlight"

Interlochen, Michigan * Bob James and Nancy Stagnitta "In the Chapel in the Moonlight" Saturday, March 4, 2017 2:30pm, Dendrinos Chapel/Recital Hall 7:30pm, Dendrinos Chapel/Recital Hall PROGRAM Nancy Stagnitta, flute Bob James, piano Side A Dancing on the Water ............................................................................................ Bob James Air Apparent .................................................................... Johann Sebastian Bach/Bob James J.S. Bop ................................................................................................................. Bob James Quadrille ................................................................................................................ Bob James Heartstorm ............................................................................................................. Bob James ~ BRIEF PAUSE ~ Side B Smile .............................................................................................................. Charlie Chaplin The Bad and the Beautiful .................................................................................. David Raksin Iridescence ............................................................................................................ Bob James Bijou/Scrapple from the Chapel ................................................... Bob James/Nancy Stagnitta Odyssey ................................................................................................................. Bob James All compositions arranged by Bob -

Discography of the Mainstream Label

Discography of the Mainstream Label Mainstream was founded in 1964 by Bob Shad, and in its early history reissued material from Commodore Records and Time Records in addition to some new jazz material. The label released Big Brother & the Holding Company's first material in 1967, as well as The Amboy Dukes' first albums, whose guitarist, Ted Nugent, would become a successful solo artist in the 1970s. Shad died in 1985, and his daughter, Tamara Shad, licensed its back catalogue for reissues. In 1991 it was resurrected in order to reissue much of its holdings on compact disc, and in 1993, it was purchased by Sony subsidiary Legacy Records. 56000/6000 Series 56000 mono, S 6000 stereo - The Commodore Recordings 1939, 1944 - Billy Holiday [1964] Strange Fruit/She’s Funny That Way/Fine and Mellow/Embraceable You/I’ll Get By//Lover Come Back to Me/I Cover the Waterfront/Yesterdays/I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues/I’ll Be Seeing You 56001 mono, S 6001 stereo - Begin the Beguine - Eddie Heywood [1964] Begin the Beguine/Downtown Cafe Boogie/I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me/Carry Me Back to Old Virginny/Uptown Cafe Boogie/Love Me Or Leave Me/Lover Man/Save Your Sorrow 56002 mono, S 6002 stereo - Influence of Five - Hawkins, Young & Others [1964] Smack/My Ideal/Indiana/These Foolish Things/Memories Of You/I Got Rhythm/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/Stardust/Sittin' In/Just A Riff 56003 mono, S 6003 stereo - Dixieland-New Orleans - Teagarden, Davison & Others [1964] That’s A- Plenty/Panama/Ugly Chile/Riverboat Shuffle/Royal Garden Blues/Clarinet -

Lush's Final Show @ Manchester Academy

LUSH’S FINAL SHOW @ MANCHESTER ACADEMY larecord.com /photos/2016/11/26/lushs-final-show-manchester-academy November 26th, 2016 | Photos Photos by Todd Nakamine 2016 brought a very successful return for Lush with sold out shows, festival appearances and a new EP Blind Spot. But 2016 also brought the final show the band would play at the Manchester Academy to a somewhat somber crowd. We were soaking in every last note all knowing this was the last show ever (sometimes knowing is worse). Kicking off their high energy set with “De-luxe” and plowing through classic after classic covering their entire career including “Kiss Chase,” “Thoughtforms,” “Etheriel,” “Light From A Dead Star,” “Hypocrite,” “Undertow” plus the new already classic Lush track “Out of Control.” While nothing can replace the late Chris Acland’s subtleties that helped define Lush’s sound, drummer Justin Welsh’s hard and fast style of playing added an extra kick apparent in songs like “Ladykiller,” or as Miki Berenyi said should be renamed “Pussygrabber” in light of U.S.A.’s new president elect, as well as “Sweetness and Light.” Acland’s close friend Michael Conroy of Modern English filled in on bass as Phil King left the band in October. Finishing with the final song of the night “Monochrome,” Emma Anderson, Berenyi and Welsh gave their last waves, left the stage for the final time and the crowd quietly shuffled out having been treated with a very special goodbye. Kicking off the night was Brix & The Extricated featuring post punk legends Brix Smith, Steve Hanley and Paul Hanley (The Fall). -

French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed As a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G. Cale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Cale, John G., "French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2112. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2112 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72-17,750 CALE, John G., 1922- FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College;, Ph.D., 1971 Music I University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by John G. Cale B.M., Louisiana State University, 1943 M.A., University of Michigan, 1949 December, 1971 PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. -

Insufficient Concern: a Unified Conception of Criminal Culpability

Insufficient Concern: A Unified Conception of Criminal Culpability Larry Alexandert INTRODUCTION Most criminal law theorists and the criminal codes on which they comment posit four distinct forms of criminal culpability: purpose, knowl- edge, recklessness, and negligence. Negligence as a form of criminal cul- pability is somewhat controversial,' but the other three are not. What controversy there is concerns how the lines between them should be drawn3 and whether there should be additional forms of criminal culpabil- ity besides these four.' My purpose in this Essay is to make the case for fewer, not more, forms of criminal culpability. Indeed, I shall try to demonstrate that pur- pose and knowledge can be reduced to recklessness because, like reckless- ness, they exhibit the basic moral vice of insufficient concern for the interests of others. I shall also argue that additional forms of criminal cul- pability are either unnecessary, because they too can be subsumed within recklessness as insufficient concern, or undesirable, because they punish a character trait or disposition rather than an occurrent mental state. Copyright © 2000 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Incorporated (CLR) is a California nonprofit corporation. CLR and the authors are solely responsible for the content of their publications. f Warren Distinguished Professor of Law, University of San Diego. I wish to thank all the participants at the Symposium on The Morality of Criminal Law and its honoree, Sandy Kadish, for their comments and criticisms, particularly Leo Katz and Stephen Morse, who gave me comments prior to the event, and Joshua Dressler, whose formal Response was generous, thoughtful, incisive, and prompt. -

Recent Critical Praise for My Brightest Diamond's This Is My Hand

Recent critical praise for My Brightest Diamond’s This Is My Hand Favorite Songs of 2014 “‘Pressure’: This baroque pop gem opens with drum corps and woodwinds, tacks on a tribal rhythm breakdown and just goes for it. All the way.” “…one of the most powerful and dramatic voices of the past decade.” “…an ability to cultivate intimacy through flawless, complex production with a beating heart.” “As a musician, Worden (who performs as My Brightest Diamond) builds her songs deliberately and impeccably…words are painted, sounds are sculpted, and the nature of Worden’s voice itself adds dimension—more than a single vocalist usually can. Her wholly enveloping, finely tuned alto sounds by turns forceful, vulnerable, cooing, playful, and endlessly emotive.” “…has a feeling for both the grandeur and the grain, building every sweeping gesture in her music out of a swarm of small details.” The Best of 2014 “…added to her smart, savvy chamber pop the influence of funk and marching bands. Her flawless voice pecks, jabs and floats above a world of rhythm that gives the new music its motion and undeniable heartbeat.” “At times, This Is My Hand all but commands listeners to dance.” “On her new album, This Is My Hand, she continues to reach far and wide with great success, adding marching-band rhythms and funky horns to her mix.” “…sounds like a modern-day Nina Simone…” “…This is My Hand works on a visceral level, conjuring Worden’s intended image of tribal, fireside collaboration through a rich diversity of texture, detail, and tone.” “…successful exercise in percussive, jagged art-pop that explores themes of self-acceptance, sensuality, and community.” “...unique and oddly beautiful.” “…presents an invigorating progression of Worden’s sonic palette…” #3: MBE Producer Ariana Morgenstern’s Top Albums of 2014 “…gorgeous new album…” “This Is My Hand is an album I would recommend to anyone—for exactly all the reasons that it’s hard to write about. -

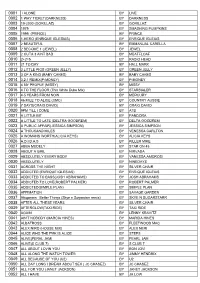

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

DISTRIBUTING PRODUCTIVE PLAY: a MATERIALIST ANALYSIS of STEAM Daniel Joseph Doctor of Philosophy Ryerson University, 2017

DISTRIBUTING PRODUCTIVE PLAY: A MATERIALIST ANALYSIS OF STEAM by Daniel Joseph Master of Arts, Ryerson University and York University, Toronto, Ontario 2011 Bachelor of Arts, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, 2009 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Daniel Joseph, 2017 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract DISTRIBUTING PRODUCTIVE PLAY: A MATERIALIST ANALYSIS OF STEAM Daniel Joseph Doctor of Philosophy Ryerson University, 2017 Valve Corporation’s digital game distribution platform, Steam, is the largest distributor of games on personal computers, analyzed here as a site where control over the production, design and use of digital games is established. Steam creates and exercises processes and techniques such as monopolization and enclosure over creative products, online labour, and exchange among game designers. Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding framework places communication at the centre of the political economy, here of digital commodities distributed and produced by online platforms like Steam. -

BAM Announces Its Bamcafe Live November Music Programming Featuring Jazz, Middle Eastern, Chamber Pop, Baroque Cabaret, and Hip-Hop

Brooklyn 30 Lafayette Avenue Communications Department Academy Brooklyn NY 11217-1486 Sandy Sawotka of Telephone: 718.636.4111 Fatima Kafele Music Fax: 718.857.2021 Jennifer Lam 718.636.4129 [email protected] News Release BAM Announces its BAMcafe Live November Music Programming Featuring Jazz, Middle Eastern, Chamber Pop, Baroque Cabaret, and Hip-Hop Highlights include the NextNext music series showcase, modern jazz arrangements of Bjork's music, the Middle Eastern musical hybrid of Shusmo, chamber pop with Greta Gertler, the jazz fusion of Fred Ho and the Afro Asian Music Ensemble, pop-cabaret with Daniel Isengart, the ukulele/viola sounds of Songs from a Random House, and a Thanksgiving holiday weekend hip-hop extravaganza with Akim Funk Buddha No cover! $10 food/drink minimum, Friday-Saturday BROOKLYN, October 4, 2005-As part of BAM's 2005 Next Wave Festival, BAMcafe Live, the performance series curated by Limor Tomer, presents an eclectic mix of jazz, spoken word, rock, pop, and world beat Friday and Saturday nights. BAMcafe Live events have no cover charge ($1 0 food/drink minimum). For information and updates, call 718.636.4139 or visit www.bam.org. (For press reservations and photos, contact Fatima Kafele at 718.636.4129 x4 or [email protected]). BAMcafe kicks off a month of great music with Travis Sullivan's Bjorkestra (November 4), a group that crafts modem jazz arrangements of Bjork's visionary techno pop. The next night (November 5), Shusmo concludes the NextNext series of talented musicians in their 20s, with an eclectic, Middle Eastern blend of jazz and Latin Rhythms. -

DJ Playlist.Djp

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

Piatkus Non-Fiction Backlist Translation Rights

PIATKUS NON-FICTION BACKLIST TRANSLATION RIGHTS Contents: Non-fiction p.2 Mind, Body & Spirit p.11 Health p.30 Patrick Holford p.42 Self-help/Popular Psychology p.54 Sex p.76 Memoir p.78 Humour p.87 Business p.89 ANDY HINE Rights Director (for Brazil, Germany, Italy, Poland, Scandinavia, Latin America) [email protected] KATE HIBBERT Rights Director (for the USA, Spain, Portugal, Far East and the Netherlands) [email protected] HELENA DOREE Senior Rights Manager (for France, Turkey, Arab States, Israel, Greece, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Macedonia and the Baltic States) [email protected] JONATHAN HAINES Rights Assistant [email protected] Carmelite House 50 Victoria Embankment London EC4Y 0DZ Tel: +44 (0) 20 3122 6209 1 NON-FICTION CONNED by James Morton A racy, highly entertaining history of cons and conmen. To the many people who've been the subject of a con, this book will be of personal interest: even if you haven't, there's still a fascination in how it has happened to other. The great, the god and the bad, from Oscar Wilde to Al Capone, have fallen victim to the wiles of the trickster. In Capone's case, he purchased a machine from 'Count' Victor Lustig, guaranteed to produce dollar bills. Other great cons described in this alarming yet funny book are: Royal Cons, Psychic Swindlers, Fairground Cons, Sexual Swindles, and Gambling Swindles. James Morton’s previous books include the bestselling GANGLAND and EAST END GANGLAND. THE BEASTLY BATTLES OF OLD ENGLAND by Nigel Cawthorne Throughout history the English have been a warlike lot.