Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Versus "Infringing": Different Interpretations of the Word "Work" and the Effect on the Deterrence Goal of Copyright Law Sarah A

Marquette Intellectual Property Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 1 Article 4 "Infringed" Versus "Infringing": Different Interpretations of the Word "Work" and the Effect on the Deterrence Goal of Copyright Law Sarah A. Zawada Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/iplr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons Repository Citation Sarah A. Zawada, "Infringed" Versus "Infringing": Different Interpretations of the Word "Work" and the Effect on the Deterrence Goal of Copyright Law, 10 Intellectual Property L. Rev. 129 (2006). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/iplr/vol10/iss1/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Intellectual Property Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ZAWADA ARTICLE - FORMATTED 4/24/2006 6:52:27 AM “Infringed” Versus “Infringing”: Different Interpretations of the Word “Work” and the Effect on the Deterrence Goal of Copyright Law I. INTRODUCTION One of the key elements that courts use to determine an appropriate statutory damage award in a copyright infringement case is the number of infringements of a copyright.1 In most cases, the number of infringements of a copyright is obvious. For example, if a publishing company reprints an author’s copyrighted book without her permission, the author is entitled to one statutory damage award. Similarly, if a recording company includes one of a composer’s copyrighted songs without his permission on an album, the composer is entitled to one statutory damage award. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/222 - Total : 8629 Vinyls Au 05/10/2021 Collection "Artistes Divers Toutes Catã©Gorie

Collection "Artistes divers toutes catégorie. TOUT FORMATS." de yvinyl Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage !!! !!! LP GSL39 Etats Unis Amerique 10cc Windows In The Jungle LP MERL 28 Royaume-Uni 10cc The Original Soundtrack LP 9102 500 France 10cc Ten Out Of 10 LP 6359 048 France 10cc Look Hear? LP 6310 507 Allemagne 10cc Live And Let Live 2LP 6641 698 Royaume-Uni 10cc How Dare You! LP 9102.501 France 10cc Deceptive Bends LP 9102 502 France 10cc Bloody Tourists LP 9102 503 France 12°5 12°5 LP BAL 13015 France 13th Floor Elevators The Psychedelic Sounds LP LIKP 003 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Live LP LIKP 002 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Easter Everywhere LP IA 5 Etats Unis Amerique 18 Karat Gold All-bumm LP UAS 29 559 1 Allemagne 20/20 20/20 LP 83898 Pays-Bas 20th Century Steel Band Yellow Bird Is Dead LP UAS 29980 France 3 Hur-el Hürel Arsivi LP 002 Inconnu 38 Special Wild Eyed Southern Boys LP 64835 Pays-Bas 38 Special W.w. Rockin' Into The Night LP 64782 Pays-Bas 38 Special Tour De Force LP SP 4971 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Strength In Numbers LP SP 5115 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Special Forces LP 64888 Pays-Bas 38 Special Special Delivery LP SP-3165 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Rock & Roll Strategy LP SP 5218 Etats Unis Amerique 45s (the) 45s CD hag 009 Inconnu A Cid Symphony Ernie Fischbach And Charles Ew...3LP AK 090/3 Italie A Euphonius Wail A Euphonius Wail LP KS-3668 Etats Unis Amerique A Foot In Coldwater Or All Around Us LP 7E-1025 Etats Unis Amerique A's (the A's) The A's LP AB 4238 Etats Unis Amerique A.b. -

DISTRIBUTING PRODUCTIVE PLAY: a MATERIALIST ANALYSIS of STEAM Daniel Joseph Doctor of Philosophy Ryerson University, 2017

DISTRIBUTING PRODUCTIVE PLAY: A MATERIALIST ANALYSIS OF STEAM by Daniel Joseph Master of Arts, Ryerson University and York University, Toronto, Ontario 2011 Bachelor of Arts, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, 2009 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Daniel Joseph, 2017 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract DISTRIBUTING PRODUCTIVE PLAY: A MATERIALIST ANALYSIS OF STEAM Daniel Joseph Doctor of Philosophy Ryerson University, 2017 Valve Corporation’s digital game distribution platform, Steam, is the largest distributor of games on personal computers, analyzed here as a site where control over the production, design and use of digital games is established. Steam creates and exercises processes and techniques such as monopolization and enclosure over creative products, online labour, and exchange among game designers. Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding framework places communication at the centre of the political economy, here of digital commodities distributed and produced by online platforms like Steam. -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

The Origins and Meaning of the Intellectual Property Clause

THE ORIGINS AND MEANING OF THE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY CLAUSE Dotan Oliar* ABSTRACT In Eldred v. Ashcroft (2003) the Supreme Court reaffirmed the primacy of historical and textual considerations in delineating Congress’ power and limitations under the Intellectual Property Clause. Nevertheless, the Court overlooked what is perhaps the most important source of information regarding these considerations: The debates in the federal Constitutional Convention that led to the adoption of the Clause. To date, several unsettled questions stood in the way of identifying fully the legislative history behind the Clause. Thus, the Article goes through a combined historical and quantitative fact-finding process that culminates in identifying eight proposals for legislative power from which the Clause originated. Having clarified the legislative history, the Article proceeds to examine the process by which various elements of these proposals were combined to produce the Clause. This process of textual putting together reveals, among other things, that the text “promote the progress of science and useful arts” serves as a limitation on Congress’ power to grant intellectual property rights. The Article offers various implications for intellectual property doctrine and policy. It offers a model to describe the power and limitations set in the Clause. It examines the way in which Courts have enforced the limitations in the Clause. It reveals a common thread of non-deferential review running through Court decisions to date, for which it supplies normative justifications. It thus concludes that courts should examine in future and pending cases whether the Progress Clause’s limitation has been overreached. Since Eldred and other cases have not developed a concept of progress for the Clause yet, the Article explores several ways in which courts could do so. -

Pimps and Ferrets Pimps and Ferrets: Copyright and Culture in the United States: 1831-1891

Pimps and Ferrets Pimps and Ferrets: Copyright and Culture in the United States: 1831-1891 Version 1.1 September 2010 Eric Anderson Version 1.1 © 2010 by Eric Anderson [email protected] This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA Some Rights Reserved A Note on this Book Humanities academics in the United States generally receive little payment from the sale of books they have written. Instead, scholars write in an economy of prestige, promotion, and duty. Prestige comes from publishing with a reputable university press, from being well-reviewed in important academic journals, and from the accolades of academic peers. For a professionally young academic in the humanities at a medium-ranked institution in the United States, a peer-reviewed book at a mid-ranked University Press is essential for tenure and promotion. The doctoral dissertation (sometimes quite heavily revised) typically forms the core of this first academic book and sometimes several additional articles. Occasionally maligned, the the usual alternative to tenure is termination. Promotion (i.e. from Assistant to Associate Professor) leads to job security and a ten or fifteen thousand dollar increase in annual salary. In this context, book royalties are a negligible incentive. This book is a lightly revised version of my doctoral dissertation, completed in December of 2007. After graduation, I submitted it to a small academic legal studies press, where it was favorably reviewed by the editor of that press and by a knowledgeable senior academic associated with the Press, and accepted for publication. -

Piatkus Non-Fiction Backlist Translation Rights

PIATKUS NON-FICTION BACKLIST TRANSLATION RIGHTS Contents: Non-fiction p.2 Mind, Body & Spirit p.11 Health p.30 Patrick Holford p.42 Self-help/Popular Psychology p.54 Sex p.76 Memoir p.78 Humour p.87 Business p.89 ANDY HINE Rights Director (for Brazil, Germany, Italy, Poland, Scandinavia, Latin America) [email protected] KATE HIBBERT Rights Director (for the USA, Spain, Portugal, Far East and the Netherlands) [email protected] HELENA DOREE Senior Rights Manager (for France, Turkey, Arab States, Israel, Greece, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Macedonia and the Baltic States) [email protected] JONATHAN HAINES Rights Assistant [email protected] Carmelite House 50 Victoria Embankment London EC4Y 0DZ Tel: +44 (0) 20 3122 6209 1 NON-FICTION CONNED by James Morton A racy, highly entertaining history of cons and conmen. To the many people who've been the subject of a con, this book will be of personal interest: even if you haven't, there's still a fascination in how it has happened to other. The great, the god and the bad, from Oscar Wilde to Al Capone, have fallen victim to the wiles of the trickster. In Capone's case, he purchased a machine from 'Count' Victor Lustig, guaranteed to produce dollar bills. Other great cons described in this alarming yet funny book are: Royal Cons, Psychic Swindlers, Fairground Cons, Sexual Swindles, and Gambling Swindles. James Morton’s previous books include the bestselling GANGLAND and EAST END GANGLAND. THE BEASTLY BATTLES OF OLD ENGLAND by Nigel Cawthorne Throughout history the English have been a warlike lot. -

Claiming Intellectual Property Jeanne C Fromert

Claiming Intellectual Property Jeanne C Fromert This Article explores the claiming systems of patent and copyright law with a view to how they affect innovation. It first develops a two-dimensional taxonomy: claiming can be either peripheralor central, and either by characteristicor by exemplar Patent law has principally adopted a system of peripheralclaiming, requiringpatentees to articulate by the time of the patent grant their invention's bound usually by listing its necessary and sufficient characteristicsAnd copyright law has implicitly adopted a system of central claiming by exemplar, requiring the articulation only of a prototypical member of the set of protected works-namely, the copyrightable work itself fixed in a tangibleform. Copyright protection then extends beyond the exemplar to substantiallysimilar works, a set of works to be enumerated only down the road in case-by-case infringement litiga- tion. Despite patent law's typical peripheralclaims by characteristicand copyright law's typical central claims by exemplar, in practice,patent and copyright claiming are each heterogeneous, in that they rely on otherforms of claiming. This Article explores which forms of claiming promote intellectual property's overarching constitutionalgoal. "To promote the Progressof Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Au- thors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries." It considers how each sort of claiming affects the costs of drafting claims, efficacy of no- tice to the public of the set of protected embodiments, ascertainment of protectability, breadth of the set of protected works, and the protectability of works grounded in after- developed technologies. With the goal of stimulating innovation, I suggest that patent law can be tweaked by adding claiming elements more reminiscent of copyright law, namely central claims and claims by exemplar. -

Artículo (376.0Kb)

Páez, Daniela La conformación de un campo editorial global : el nuevo escenario para la circulación de las ideas y su impacto en el mercado local Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Argentina. Atribución - No Comercial - Sin Obra Derivada 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ar/ Documento descargado de RIDAA-UNQ Repositorio Institucional Digital de Acceso Abierto de la Universidad Nacional de Quilmes de la Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Cita recomendada: Páez, D. (2017) La conformación de un campo editorial global: el nuevo escenario para la circulación de las ideas y su impacto en el mercado argentino. Divulgatio. Perfiles académicos de posgrado, 2(4), 104-119. Disponible en RIDAA-UNQ Repositorio Institucional Digital de Acceso Abierto de la Universidad Nacional de Quilmes http://ridaa.unq.edu.ar/handle/20.500.11807/2768 Puede encontrar éste y otros documentos en: https://ridaa.unq.edu.ar Divulgatio. Perfiles académicos de posgrado, Vol. 2, Número 4, 2017, 104-119. La conformación de un campo editorial global: el nuevo escenario para la circulación de las ideas y su impacto en el mercado argentino The conformation of a global publishing field: the new scenario for the circulation of ideas and its impact in the Argentinian market ARTÍCULO Daniela Páez Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, Argentina. Contacto: [email protected] Recibido: septiembre de 2017 Aceptado: octubre de 2017 Resumen El presente artículo se enfoca en analizar las condiciones de circulación de libros e ideas del campo editorial global, un espacio que está integrado por múltiples actores con desiguales capacidades de acción e influencia en el sistema, que comenzó a consolidarse a partir de la década de 1980. -

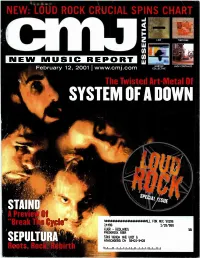

System of a Down Molds Metal Like Silly Putty, Bending and Shaping Its Parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment Ters to Fit the Band's Twisted Vision

NEW: LOUD ROCK CRUCIAL SPINS CHART LOW TORTOISE 1111 NEW MUSIC REPORT Uà NORTEC JACK COSTANZO February 12, 20011 www.cmj.com COLLECTIVE The Twisted Art-Metal Of SYSTEM OF ADOWN 444****************444WALL FOR ADC 90138 24438 2/28/388 KUOR - REDLAHDS FREDERICK SUER S2V3HOD AUE unr G ATASCADER0 CA 88422-3428 IIii II i ti iii it iii titi, III IlitlIlli lilt ti It III ti ER THEIR SELF TITLED DEBUT AT RADIO NOW • FOR COLLEGE CONTACT PHIL KASO: [email protected] 212-274-7544 FOR METAL CONTACT JEN MEULA: [email protected] 212-274-7545 Management: Bryan Coleman for Union Entertainment Produced & Mixed by Bob Marlette Production & Engineering of bass and drum tracks by Bill Kennedy a OADRUNNEll ACME MCCOWN« ROADRUNNER www.downermusic.com www.roadrunnerrecords.com 0 2001 Roadrunner Records. Inc. " " " • Issue 701 • Vol 66 • No 7 FEATURES 8 Bucking The System member, the band is out to prove it still has Citing Jane's Addiction as a primary influ- the juice with its new release, Nation. ence, System Of A Down molds metal like Silly Putty, bending and shaping its parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment ters to fit the band's twisted vision. Loud Follies Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto taps SOAD for Free speech is fodder for the courts once the scoop on its upcoming summer release. again. This time the principals involved are a headbanger institution and the parents of 10 It Takes A Nation daughter who was brutally murdered by three Some question whether Sepultura will ever of its supposed fans. be same without larger-than-life frontman 15 CM/A: Staincl Max Cavalera. -

B E RT E LS MA N N Media Worldwide

Information Memorandum Borsenzulassungsprospekt (gemal3 0 44 BorsZulV) B E RT E LS MA N N media worldwide Bertelsmann AG (Gutersloh, Federal Republic of Germany) as Issuer and, in respect of Notes issued by Bertelsmann Capital Corporation N.V. or Bertelsmann U. S. Finance, Inc., as Guarantor Bertelsmann Capital Corporation N. V. (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) as Issuer Bertelsmann U. S. Finance, Inc. (Wilmington, Delaware,U. SA.) as Issuer Euro 3,000,000,000 Debt lssua nce Programme The notes (the "Notes") to be issued under the Euro 3,000,000,000 Debt Issuance Programme (the "Programme") are admitted for official quotation on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange and application has been made to list Notes issued under the Programme on the Luxembourg Stock Exchange. Notes issued under the Programme may also be listed on an alternative stock exchange or may not be listed at all. The payments of all amounts due in respect of Notes issued by Bertelsmann Capital Corporation N.V. and Bertelsmann U. S. Finance, Inc. will be unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed by Bertels- mann AG. Arranger Deutsche Bank Dealers ABN AMRO Commerzbank Securities Credit Suisse First Boston Deutsche Bank Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein JPMorgan Merrill Lynch International Schroder Salomon Smith Barney UBS Warburg The date of this Information Memorandum (which for purposes of a listing of Notes on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange serves as "Borsenzulassungsprospekt") is 6 June 2002. The Information Memoran- dum is valid for one year from such date. Bertelsmann AG ("Bertelsmann" and together with all of its affiliated companies within the meaning of the German Stock Corporation Act (Aktiengeserz), the "Bertelsmann Group"), Bertelsmann Capital Corporation N.V.