Cash Transfers and Resilience in Chad: Overview of Experiences and Case Study of Care’S Interventions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kanem Rural Development Project (Proder-K) Project Completion Report Validation

IFAD - REPUBLIC OF CHAD KANEM RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (PRODER-K) PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT VALIDATION A. Basic Data A. Basic Project Approval (US$ Actual Data m) (US$ m) Region WCA Total project costs 14.3 Country Republic of IFAD Loan and % of 13.0 90.8% Chad total Loan Number 607-TD Borrower 1.0 7.1% Type of project Rural Co-financier 1 (sub-sector) development Financing Type Loan Co-financier 2 Lending Terms1 HI Co-financier 3 Date of Approval April 2003 Co-financier 4 Date of Loan 15 May 2003 From Beneficiaries 300,000 2.1% Signature Date of 15 May 2005 From Other Sources: Effectiveness Loan Amendments None Number of beneficiaries 90,000 – 8,560 (if appropriate, specify if 100,000 direct direct or indirect) beneficiaries Loan Closure Cooperating Institution UNOPS UNOPS Extensions Country L.L. Nsimpasi Loan Closing Date 31 December 30 June Programme U. Demirag 2013 2010 Managers M. Béavogui (ad interim) A. Lhommeau Regional M. Béavogui Mid-Term Review Mentioned in None Director(s) AR, without date PCR Reviewer Ernst IFAD Loan 26.2 Schaltegger Disbursement at project (consultant) completion (%) PCR Quality Felloni Control Panel Muthoo Please provide any comment if required Sources:Presidents Report 2003, PCR 2010 B. Project Outline 1. The project, laid out for a period of eight years, covered the region of Kanem, which comprised the departments of Kanem and Bahr-El-Ghzal, both located about 300 km North of Ndjamena. It built on experience gained through the a predecessor project, the Projet de 1 According to IFAD’s Lending Policies and Criteria, there are three types of lending terms: highly concessional (HI), intermediate (I) and ordinary (O). -

Central African Republic (C.A.R.) Appears to Have Been Settled Territory of Chad

Grids & Datums CENTRAL AFRI C AN REPUBLI C by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “The Central African Republic (C.A.R.) appears to have been settled territory of Chad. Two years later the territory of Ubangi-Shari and from at least the 7th century on by overlapping empires, including the the military territory of Chad were merged into a single territory. The Kanem-Bornou, Ouaddai, Baguirmi, and Dafour groups based in Lake colony of Ubangi-Shari - Chad was formed in 1906 with Chad under Chad and the Upper Nile. Later, various sultanates claimed present- a regional commander at Fort-Lamy subordinate to Ubangi-Shari. The day C.A.R., using the entire Oubangui region as a slave reservoir, from commissioner general of French Congo was raised to the status of a which slaves were traded north across the Sahara and to West Africa governor generalship in 1908; and by a decree of January 15, 1910, for export by European traders. Population migration in the 18th and the name of French Equatorial Africa was given to a federation of the 19th centuries brought new migrants into the area, including the Zande, three colonies (Gabon, Middle Congo, and Ubangi-Shari - Chad), each Banda, and M’Baka-Mandjia. In 1875 the Egyptian sultan Rabah of which had its own lieutenant governor. In 1914 Chad was detached governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day C.A.R.” (U.S. from the colony of Ubangi-Shari and made a separate territory; full Department of State Background Notes, 2012). colonial status was conferred on Chad in 1920. -

Chad Food Security Outlook October 2016 Through May 2017

CHAD Food Security Outlook October 2016 through May 2017 This year’s good rains improve the food security situation in Chad KEY MESSAGES Current food security outcomes for October 2016 A long growing season occurred this year, with the first rains falling a month earlier than usual, in April in the Sudanian zone and in May in Sahelian areas. There were above-average cumulative rainfall totals and a good distribution of rainfall in nearly all agropastoral areas. Cereal production is expected to be better than last year (by 16 percent) and above the five-year average (by 13 percent). The current availability of fresh crops from ongoing harvests, wild vegetables, and other wild plant foods and the availability of milk in certain localized areas have improved the food security situation in all parts of the country (except for the Lake Chad area due to the conflict). Households will have more diversified sources of food between October 2016 and January 2017 and there will be Minimal (IPC Phase 1) acute food insecurity in all parts of the country with the exception of the Lake Chad area. With the usual depletion of their food stocks between February Source: FEWS NET and May 2017, poor households in Kanem, the BEG area, This map shows relevant current acute food insecurity Abtouyour (Guera), and Kobé (Wadi Fira) will face a sharp outcomes for emergency decision-making. It does not reflect contraction in their main sources of income, namely migrant chronic food insecurity. remittances affected by the national economic crisis and livestock sales affected by the suspension of exports to Nigeria, as well as economic pressure from IDPs in Kanem and the BEG area. -

Summary of Protected Areas in Chad

CHAD Community Based Integrated Ecosystem Management Project Under PROADEL GEF Project Brief Africa Regional Office Public Disclosure Authorized AFTS4 Date: September 24, 2002 Team Leader: Noel Rene Chabeuf Sector Manager: Joseph Baah-Dwomoh Country Director: Ali Khadr Project ID: P066998 Lending Instrument: Adaptable Program Loan (APL) Sector(s): Other social services (60%), Sub- national government administration (20%), Central government administration (20%) Theme(s): Decentralization (P), Rural services Public Disclosure Authorized and infrastructure (P), Other human development (P), Participation and civic engagement (S), Poverty strategy, analysis and monitoring (S) Global Supplemental ID: P078138 Team Leader: Noel Rene Chabeuf Sector Manager/Director: Joseph Baah-Dwomoh Lending Instrument: Adaptable Program Loan (APL) Focal Area: M - Multi-focal area Supplement Fully Blended? No Sector(s): General agriculture, fishing and forestry sector (100%) Theme(s): Biodiversity (P) , Water resource Public Disclosure Authorized management (S), Other environment and natural resources management (S) Program Financing Data Estimated APL Indicative Financing Plan Implementation Period Borrower (Bank FY) IDA Others GEF Total Commitment Closing US$ m % US$ m US$ m Date Date APL 1 23.00 50.0 17.00 6.00 46.00 11/12/2003 10/31/2008 Government of Chad Loan/ Credit APL 2 20.00 40.0 30.00 0 50.00 07/15/2007 06/30/2012 Government of Chad Loan/ Credit Public Disclosure Authorized APL 3 20.00 33.3 40.00 0 60.00 03/15/2011 12/31/2015 Government of Chad Loan/ Credit Total 63.00 93.00 156.00 1 [ ] Loan [X] Credit [X] Grant [ ] Guarantee [ ] Other: APL2 and APL3 IDA amounts are indicative. -

Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+

CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ A tree provides shelter for a meeting with a community of returnees in Borota, Ouaddai Region. Pierre Peron / OCHA CHAD Consolidated Appeal Mid-Year Review 2013+ CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ Participants in 2013 Consolidated Appeal A AFFAIDS, ACTED, Action Contre la Faim, Avocats sans Frontières, C CARE International, Catholic Relief Services, COOPI, NGO Coordination Committee in Chad, CSSI E ESMS F Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations I International Medical Corps UK, Intermon Oxfam, International Organization for Migration, INTERSOS, International Aid Services J Jesuit Relief Services, JEDM, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS M MERLIN O Oxfam Great Britain, Organisation Humanitaire et Développement P Première Urgence – Aide Médicale Internationale S Solidarités International U United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, United Nations Development Programme, UNAD, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations Children’s Fund W World Food Programme, World Health Organization. Please note that appeals are revised regularly. The latest version of this document is available on http://unocha.org/cap. Full project details, continually updated, can be viewed, downloaded and printed from http://fts.unocha.org. CHAD CONSOLIDATED APPEAL MID-YEAR REVIEW 2013+ TABLE OF CONTENTS REFERENCE MAP ................................................................................................................................ -

Working Paper 2017-06

worki! ownng pap er 2017-06 Universite Laval The impact of oil exploitation on wellbeing in Chad Gadom Djal Gadom Armand Mboutchouang Kountchou Gbetoton Nadège Adèle Djossou Gilles Quentin Kane Abdelkrim Araar February 2017 i The impact of oil exploitation on wellbeing in Chad Abstract This study assesses the impact of oil revenues on wellbeing in Chad using data from the two last Chad Household Consumption and Informal Sector Surveys (ECOSIT 2 & 3), conducted in 2003 and 2011, respectively, by the National Institute of Statistics for Economics and Demographic Studies (INSEED) and, from the College for Control and monitoring of Oil Revenues (CCSRP). To achieve the research objective, we first estimate a synthetic index of multidimensional wellbeing (MDW) based on a large set of welfare indicators. Then, the Difference-in-Difference (DID) approach is used to assess the impact of oil revenues on the average MDW at departmental level. We find evidence that departments receiving intense oil transfers increased their MDW about 35% more than those disadvantaged by the oil revenues redistribution policy. Moreover, the further a department is from the capital city N’Djamena, the lower its average MDW. We conclude that to better promote economic inclusion in Chad, the government should implement a specific policy to better direct the oil revenue investment in the poorest departments. Keys words: Poverty, Multidimensional wellbeing, Oil exploitation, Chad, Redistribution policy. JEL Codes: I32, D63, O13, O15 Authors Gadom Djal Gadom Mboutchouang -

FAO Desert Locust Bulletin 192 (English)

page 1 / 7 FAO EMERGENCY CENTRE FOR LOCUST OPERATIONS DESERT LOCUST BULLETIN No. 192 GENERAL SITUATION DURING AUGUST 1994 FORECAST UNTIL MID-OCTOBER 1994 No significant Desert Locust populations have been reported during August and the overall situation whilst still requiring vigilance, appears calm, with no major chance to develop during the forecast period. In West Africa, only scattered adults and hoppers were reported limited primarily to southern Mauritania. This would indicate that swarms from northern Mauritania dispersed earlier in the year before the onset of the rainy season and, as a result, breeding in the south was limited. No other significant locust activity has been reported from Mali, Niger and Chad. In South- West Asia, a few patches of hoppers have been treated in Rajasthan over a small area, and low density adults persisting in several locations of the summer breeding areas of India and Pakistan are likely to continue to breed; however, no major developments are expected during the forecast period. A few mature adults have been reported in the extreme south-eastern desert of Egypt and some isolated adults were present on the northern coastal plains of Somalia in late July. No locusts were reported from Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen or Oman. Conditions were reported as dry in Algeria and no locust activity was reported; a similar situation is expected to prevail in Morocco. Although the overall situation does not appear to be critical and may decline in the next few months, FAO recommends continued monitoring in the summer breeding areas. The FAO Desert Locust Bulletin is issued monthly, supplemented by Updates during periods of increased Desert Locust activity, and is distributed by fax, telex, e-mail, FAO pouch and airmail by the Emergency Centre for Locust Operations, AGP Division, FAO, 00100 Rome, Italy. -

Myr 2010 Chad.Pdf

ORGANIZATIONS PARTICIPATING IN CONSOLIDATED APPEAL CHAD ACF CSSI IRD UNDP ACTED EIRENE Islamic Relief Worldwide UNDSS ADRA FAO JRS UNESCO Africare Feed the Children The Johanniter UNFPA AIRSERV FEWSNET LWF/ACT UNHCR APLFT FTP Mercy Corps UNICEF Architectes de l’Urgence GOAL NRC URD ASF GTZ/PRODABO OCHA WFP AVSI Handicap International OHCHR WHO BASE HELP OXFAM World Concern Development Organization CARE HIAS OXFAM Intermon World Concern International CARITAS/SECADEV IMC Première Urgence World Vision International CCO IMMAP Save the Children Observers: CONCERN Worldwide INTERNEWS Sauver les Enfants de la Rue International Committee of COOPI INTERSOS the Red Cross (ICRC) Solidarités CORD IOM Médecins Sans Frontières UNAIDS CRS IRC (MSF) – CH, F, NL, Lux TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................. 1 Table I: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by cluster) ................................................... 3 Table II: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by appealing organization).......................... 4 Table III: Summary of requirements and funding (grouped by priority)................................................... 5 2. CHANGES IN THE CONTEXT, HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE ........................................... 6 3. PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES AND SECTORAL TARGETS .......... 9 3.1 STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................ -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Chad

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO CHAD Original Map Courtesy of the UN Cartographic Section 15° 20° 25° The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. Government. EGYPT CHAD LIBYA TIBESTITIBESTI Aozou Bardaï SUDAN Zouar 20° Séguédine EASTERN CHAD . ASI ? .. .. .. .. .. Bilma . .. FAO . ... BORKOUBORKO. .U ... ENNEDIENNEDI OCHA B UNICEF J . .. .. .. ° . .. .. Faya-Largeau .. .... .... ..... NIGER . .. .. .. .. .. WFP/UNHAS ? .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... ... ... .. .. .... WFP . ... .. WESTERN CHAD ... ... Fada .. ..... .. .... ASI ? . .... ACF . Committee d’Aide Médicale UNICEF J CORD WFP WADI FIRA Koro HIAS j D ICRC Toro CRS C ICRC G UNHCR Iriba 15 IFRC KANEMKANEM Arada WADIWADI FIRAFIRA J BAHRBAHR ELEL OUADDAÏ IMC ° Nokou Guéréda GAZELGAZEL Biltine ACTED Internews Nguigmi J Salal Am Zoer Mao BATHABATHA CRS C IRC JG Abéché Jesuit Refugee Service LACLAC IMC Bol Djédaa Ngouri Moussoro Oum Première Mentor Initiative Ati Hadjer OUADDAOOUADDAÏUADDAÏ Urgence OXFAM GB J Massakory IFRC IJ Refugee Ed. Trust HADJER-LAMISHADJER-LAMIS Am Dam Goz Mangalmé Première Urgence Bokoro Mongo Beïda UNHAS ? Maltam I Camp N'Djamena DARDAR SILASILA WCDO Gamboru-Ngala C UNHCR Maiduguri CHARI-CHARI- Koukou G Kousseri BAGUIRMIBAGUIRMI GUERAGUERA Angarana Massenya Dar Sila NIGERIA Melfi Abou Deïa ACTED Gélengdeng J Am Timan IMC MAYO-MAYO- Bongor KEBBIKEBBI SALAMATSALAMAT MENTOR 10° Fianga ESTEST Harazé WCDO SUDAN 10° Mangueigne C MAYO-MAYO- TANDJILETANDJILE MOYEN-CHARIMOYEN-CHARI -

Seroprevalence and Molecular Characterization of Foot‐And‐Mouth

DOI: 10.1002/vms3.206 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Seroprevalence and molecular characterization of foot‐and‐ mouth disease virus in Chad Arada Izzedine Abdel‐Aziz1,2,3,4 | Aurore Romey1 | Anthony Relmy1 | Kamila Gorna1 | Eve Laloy1 | Raphaelle Métras2,5 | Facundo Muñoz2,5 | Sandra Blaise‐Boisseau1 | Stephan Zientara1 | Renaud Lancelot2,5 | Labib Bakkali Kassimi1 1Laboratoire de Santé Animale de Maisons‐Alfort, UMR Virologie Abstract 1161, INRA, École Nationale Vétérinaire This study aimed at determining the seroprevalence of foot‐and‐mouth disease (FMD) d’Alfort, ANSES, Université Paris‐Est, Maisons‐Alfort, France in domestic ruminants and at characterizing the virus strains circulating in four areas 2CIRAD, UMR ASTRE, Montpellier, France of Chad (East Batha, West Batha, Wadi Fira and West Ennedi). The study was carried 3Institut de Recherches en Élevage pour le out between October and November 2016. A total of 1,520 sera samples (928 cat‐ Développement (IRED), N’Djamena, Tchad tle, 216 goats, 254 sheep and 122 dromedaries) were collected randomly for FMD 4Université de N’Djamena, N’Djamena, Tchad serological analyses. Nine epithelial tissue samples were also collected from cattle 5ASTRE, Université de showing clinical signs, for FMDV isolation and characterization. Serological results Montpellier, CIRAD, INRA, Montpellier, showed an overall NSP seroprevalence of 40% (375/928) in cattle in our sample (95% France CrI [19–63]). However, seroprevalences of 84% (27/32), 78% (35/45) and 84% (21/25) Correspondence were estimated in cattle over 5 years of age in East Batha, West Batha and Wadi Arada Izzedine Abdel‐Aziz, Laboratoire de Santé Animale de Maisons‐Alfort, UMR Fira, respectively. In cattle under 1 year of age, 67% (18/27) seroprevalence was esti‐ Virologie 1161, INRA, École Nationale mated in Wadi Fira, 64% (14/22) in East Batha and 59% (13/22) in West Batha. -

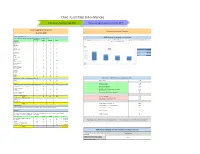

Chad Asset Map (At-A-Glance)

Chad Asset Map (At-a-Glance) Simulation Excercise Q4 2016 Transition plan expected by Q2 2017 Asset Mapping Data Overview General Information Overview As of July 2016 A. Polio Funded Personnel Number of HR per organization and regions involved in polio eradication in Chad GPEI Funding Ramp Down information Ministry of WHO UNICEF Total GPEI budget curve for polio eradication efforts in Chad from 2016-2019,a decrease in the budget from $18,326,000 to $8,097,000, a 56% PROVINCE Health decrease from 2016 to 2019 Niveau central 0 11 7 18 Njamena 0 5 7 12 Bahr Elghazal 0 2 2 4 Batha 0 2 0 2 Borkou 0 0 0 0 Chari Baguirmi 0 5 4 9 Year Funding Amount Dar Sila 0 3 2 5 2016 18,326,000 Ennedi Est 0 0 0 0 2017 12,047,000 Ennedi Ouest 0 0 0 0 2018 9,566,000 Guera 0 2 4 6 2019 8,097,000 Hadjer Lamis 0 1 2 3 Kanem 0 2 4 6 Lac 0 6 5 11 Logone Occidental 0 5 6 11 Logone Oriental 0 2 3 5 Mandoul 0 2 1 3 Mayo Kebbi Est 0 4 2 6 Mayo Kebbi Ouest 0 1 4 5 Moyen Chari 0 6 7 13 Ouaddai 0 3 3 6 Salamat 0 3 2 5 Tandjile 0 0 2 2 Tibesti 0 0 0 0 Wadi Fira 0 2 2 4 TOTAL 0 67 69 136 Time allotments of GPEI funded personnel by priority area in Chad Distribution of HR by Administrative Level of Assignment Central 0 11 7 18 Polio eradication 40.40% Régional 0 56 62 118 TOTAL 0 67 69 136 Routine Immunization 32.40% Distribution of HR involved in polio eradication by functions Measles and rubella 7.30% Implementation and service delivery 0 9 8 17 New vaccine introduction 1.40% Disease Surveillance 0 18 2 20 Child health days or weeks 0.00% Training 0 0 39 39 Maternal, newborn, and child health and nutrition 2.40% Monitoring 0 4 0 4 Health systems strengthening 3.80% Resource mobilization 0 4 2 6 Sub-total immunization related beyond polio 47% Policy and strategy 0 4 3 7 Management and operations 0 28 15 43 TOTAL 0 67 69 136 Sanitation and hygiene 0.50% Polio HR cost per administrative area Natural disasters and humanitarian crises 7.10% Central Level Other diseases or program areas 4.90% Regional Level TOTAL % of personnel formally trained in RI 100% B. -

Lake Chad Basin

Integrated and Sustainable Management of Shared Aquifer Systems and Basins of the Sahel Region RAF/7/011 LAKE CHAD BASIN 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION EDITORIAL NOTE This is not an official publication of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The content has not undergone an official review by the IAEA. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the IAEA or its Member States. The use of particular designations of countries or territories does not imply any judgement by the IAEA as to the legal status of such countries or territories, or their authorities and institutions, or of the delimitation of their boundaries. The mention of names of specific companies or products (whether or not indicated as registered) does not imply any intention to infringe proprietary rights, nor should it be construed as an endorsement or recommendation on the part of the IAEA. INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION REPORT OF THE IAEA-SUPPORTED REGIONAL TECHNICAL COOPERATION PROJECT RAF/7/011 LAKE CHAD BASIN COUNTERPARTS: Mr Annadif Mahamat Ali ABDELKARIM (Chad) Mr Mahamat Salah HACHIM (Chad) Ms Beatrice KETCHEMEN TANDIA (Cameroon) Mr Wilson Yetoh FANTONG (Cameroon) Mr Sanoussi RABE (Niger) Mr Ismaghil BOBADJI (Niger) Mr Christopher Madubuko MADUABUCHI (Nigeria) Mr Albert Adedeji ADEGBOYEGA (Nigeria) Mr Eric FOTO (Central African Republic) Mr Backo SALE (Central African Republic) EXPERT: Mr Frédèric HUNEAU (France) Reproduced by the IAEA Vienna, Austria, 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION Table of Contents 1.