Download Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wales Sees Too Much Through Scottish Eyes

the welsh + Peter Stead Dylan at 100 Richard Wyn Jones and Roger Scully Do we need another referendum? John Osmond Learning from Mondragon Stuart Cole A railway co-op for Wales David Williams Sliding into poverty James Stewart A lost broadcasting service Peter Finch Wales sees too Talking to India Trevor Fishlock The virtues of left handednesss much through Osi Rhys Osmond Two lives in art Ned Thomas Scottish eyes Interconnected European stories M. Wynne Thomas The best sort of crank www.iwa.org.uk | Summer 2012 | No. 47 | £8.99 The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges funding support from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation. The following organisations are corporate members: Public Sector Private Sector Voluntary Sector • Aberystwyth University • ABACA Limited • Aberdare & District Chamber • ACAS Wales • ACCA Cymru Wales of Trade & Commerce • Bangor University • Beaufort Research Ltd • Cardiff & Co • BBC Cymru Wales • BT • Cartrefi Cymru • British Waterways • Call of the Wild • Cartrefi Cymunedol Community • Cardiff & Vale College / Coleg • Castell Howell Foods Housing Cymru Caerdydd a’r Fro • CBI Wales • Community – the Union for Life • Cardiff Council • Core • Cynon Taf Community Housing Group • Cardiff School of Management • Darwin Gray • Disability Wales • Cardiff University • D S Smith Recycling • EVAD Trust • Cardiff University Library • Devine Personalised Gifts • Federation of Small Businesses Wales • Centre for Regeneration Excellence • Elan Valley Trust -

PLACES of ENTERTAINMENT in EDINBURGH Part 5

PLACES OF ENTERTAINMENT IN EDINBURGH Part 5 MORNINGSIDE, CRAIGLOCKHART, GORGIE AND DALRY, CORSTORPHINE AND MURRAYFIELD, PILTON, STOCKBRIDGE AND CANONMILLS, ABBEYHILL AND PIERSHILL, DUDDINGSTON, CRAIGMILLAR. ARE CIRCUSES ON THE WAY OUT? Compiled from Edinburgh Theatres, Cinemas and Circuses 1820 – 1963 by George Baird 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS MORNINGSIDE 7 Cinemas: Springvalley Cinema, 12 Springvalley Gardens, 1931; the seven cinemas on the 12 Springvalley Gardens site, 1912 – 1931; The Dominion, Newbattle Terrace, 1938. Theatre: The Church Hill Theatre; decision taken by Edinburgh Town Council in 1963 to convert the former Morningside High Church to a 440 seat theatre. CRAIGLOCKHART 11 Skating and Curling: Craiglockhart Safety Ponds, 1881 and 1935. GORGIE AND DALRY 12 Cinemas: Gorgie Entertainments, Tynecastle Parish Church, 1905; Haymarket Picture House, 90 Dalry Road, 1912 – became Scotia, 1949; Tivoli Picture House, 52 Gorgie Road, 1913 – became New Tivoli Cinema, 1934; Lyceum Cinema, Slateford Road, 1926; Poole’s Roxy, Gorgie Road, 1937. Circus: ‘Buffalo Bill’, Col. Wm. Frederick Cody, Gorgie Road, near Gorgie Station, 1904. Ice Rink: Edinburgh Ice Rink, 53 Haymarket Terrace, 1912. MURRAYFIELD AND CORSTORPHINE 27 Cinema: Astoria, Manse Road, 1930. Circuses: Bertram Mills’, Murrayfield, 1932 and 1938. Roller Skating Rink: American Roller Skating Rink, 1908. Ice Rink: Murrayfield Ice Rink; scheme sanctioned 1938; due to open in September 1939 but building was requisitioned by the Government from 1939 to 1951; opened in 1952. PILTON 39 Cinema: Embassy, Boswall Parkway, Pilton, 1937 3 STOCKBRIDGE AND CANONMILLS 40 St. Stephen Street Site: Anderson’s Ice Rink, opened about 1895;Tivoli Theatre opened on 11th November 1901;The Grand Theatre opened on 10th December 1904;Building used as a Riding Academy prior to the opening of the Grand Picture House on 31st December 1920;The Grand Cinema closed in 1960. -

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = the National Library of Wales Cymorth

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Winifred Coombe Tennant Papers, (GB 0210 WINCOOANT) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/winifred-coombe-tennant-papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/winifred-coombe-tennant-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Winifred Coombe Tennant Papers, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

Paul Kletzki ?Nachtstück Bei Territet (1904) Öl Auf Leinwand, 97 ×131 Cm 2

Koproduktion MusiquesProduktion Suisses Musiquesmit dem Polskie Suisses Radio Aufnahmen TonstudioNOSPR Konzerthalle, AMOS AG, in Kattowitz diversen (Polen) Lokalitäten 21.–23.1–3 Juni7 201618. Sept. (Kletzki) 2014, und Singsaal des 1./2. SeptemberSekundarschulhauses 2016 (Marek) Uettligen 4–6 8 18./19. Sept. 2012, Tonmeister Mühlemattsaal Trimbach Beata Jankowska-Burzyn´ska 9 26. Sept. 2014, Heimaufnahme Abmischung10–14 6. und Juni Mastering 2013, Lötschbergsaal Spiez WojciechMusikregisseur Marzec TheoExekutivproduzent Fuog TonmeisterClaudio Danuser ?GeraldEinführungstext Hahnefeld, Tonstudio Regio ChrisExekutivproduzent Walton ÜbersetzungenClaudio Danuser MichelleÜbersetzungen Bulloch – Musitext (Französisch) MichelleChris Walton Buloch (Englisch) (Französisch) ChrisCoverbild Walton (Englisch) AlexandreCoverbild Perrier (1862–1936) Paul Kletzki ?Nachtstück bei Territet (1904) Öl auf Leinwand, 97 ×131 cm 2. Sinfonie Gestaltungskonzept Paul Kletzki Gestaltungskonzeptcomvex gmbh, www.comvex.biz xx comvex gmbh, www.comvex.biz Czesław Marek Satz und Litho Satzenglerwortundbild, und Litho Zürich englerwortundbild, Zürich Sinfonia Hersteller AdonHersteller Production AG, Neuenhof Adon Production AG, Neuenhof MGB CD 6282 MGB CD 6289 Ein Projekt des MGB_6289_Booklet_Paul_Kletzki.indd 4-5 28.10.16 10:01 tice to conduct on a tour of the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, which marked the begin - ning of his international conducting career. Since then, Thomas has been invited to con - duct many orchestras, including the Deutsches Sinfonieorchester Berlin, Vienna Symphony, Bamberg Symphony, Salzburg Gesangstext in Kletzki 2. Sinfonie Mozarteum Orchestra, Houston Symphony, (Text in Klammer nicht vertont) Tokyo Symphony Orchestra, Scottish Cham- ber Orchestra, Bergen Philharmonic Orches - Schlafe, schlafe, o Welt! tra, the Orchestre National du Capitole de Leise nahet die Nacht, alles Sehnen ist still Toulouse, Basle Symphony Orchestra, Phil- und erfüllet die Zeit. hamonia Prague, Polish National Radio Or- chestra and the Israel Sinfonietta. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 77 JANUARY 28TH, 2019 Welcome to Copper #77! I hope you had a better view of the much-hyped lunar-eclipse than I did---the combination of clouds and sleep made it a non-event for me. Full moon or no, we're all Bozos on this bus---in the front seat is Larry Schenbeck, who brings us music to counterbalance the blah weather; Dan Schwartz brings us Burritos for lunch; Richard Murison brings us a non-Python Life of Brian; Jay Jay French chats with Giles Martin about the remastered White Album; Roy Hall tells us about an interesting day; Anne E. Johnson looks at lesser-known cuts from Steely Dan's long career; Christian James Hand deconstructs the timeless "Piano Man"; Woody Woodward is back with a piece on seminal blues guitarist Blind Blake; and I consider comfort music, and continue with a Vintage Whine look at Fairchild. Our reviewer friend Vade Forrester brings us his list of guidelines for reviewers. Industry News will return when there's something to write about other than Sears. Copper#77 wraps up with a look at the unthinkable from Charles Rodrigues, and an extraordinary Parting Shot taken in London by new contributor Rich Isaacs. Enjoy, and we’ll see you soon! Cheers, Leebs. Stay Warm TOO MUCH TCHAIKOVSKY Written by Lawrence Schenbeck It’s cold, it’s gray, it’s wet. Time for comfort food: Dvořák and German lieder and tuneful chamber music. No atonal scratching and heaving for a while! No earnest searches after our deepest, darkest emotions. What we need—musically, mind you—is something akin to a Canadian sitcom. -

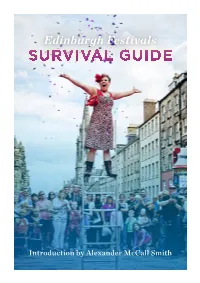

Survival Guide

Edinburgh Festivals SURVIVAL GUIDE Introduction by Alexander McCall Smith INTRODUCTION The original Edinburgh Festival was a wonderful gesture. In 1947, Britain was a dreary and difficult place to live, with the hardships and shortages of the Second World War still very much in evidence. The idea was to promote joyful celebration of the arts that would bring colour and excitement back into daily life. It worked, and the Edinburgh International Festival visitor might find a suitable festival even at the less rapidly became one of the leading arts festivals of obvious times of the year. The Scottish International the world. Edinburgh in the late summer came to be Storytelling Festival, for example, takes place in the synonymous with artistic celebration and sheer joy, shortening days of late October and early November, not just for the people of Edinburgh and Scotland, and, at what might be the coldest, darkest time of the but for everybody. year, there is the remarkable Edinburgh’s Hogmany, But then something rather interesting happened. one of the world’s biggest parties. The Hogmany The city had shown itself to be the ideal place for a celebration and the events that go with it allow many festival, and it was not long before the excitement thousands of people to see the light at the end of and enthusiasm of the International Festival began to winter’s tunnel. spill over into other artistic celebrations. There was How has this happened? At the heart of this the Fringe, the unofficial but highly popular younger is the fact that Edinburgh is, quite simply, one of sibling of the official Festival, but that was just the the most beautiful cities in the world. -

Rezension Für: Paul Kletzki

Rezension für: Paul Kletzki Paul Kletzki conducts Brahms, Schubert & Beethoven Johannes Brahms | Franz Schubert | Ludwig van Beethoven CD aud 95.642 www.pizzicato.lu 05/06/2016 (Remy Franck - 2016.06.05) Spontanes Dirigat von Paul Kletzki Der Schweizer Dirigent Paul Kletzki (1900-1973), ehemaliger Chefdirigent in Liverpool, Dallas, Bern und beim ‘Orchestre de la Suisse Romande’, dirigiert auf einer CD der Reihe ‘Lucerne Festival Historic Performances’ von Audite das ‘Swiss Festival Orchestra’. Da erklingt zunächst mit schlankem Klang, kontrastreich zwischen betonter Grübelei und drängender Aufbruchsstimmung die Vierte Symphonie von Johannes Brahms und danach eine hoch dramatische, groß-symphonisch angelegte ‘Unvollendete’ von Franz Schubert. Ebenfalls bemerkenswert ist die sehr expressive Ouvertüre ‘Leonore 3’ von Ludwig van Beethoven. Die Brahms- und Schubert –Symphonien gibt es auf anderen Labels in Studioeinspielungen, die kurz vor dem hier verwendeten, spontaneren, freieren Livemitschnitt entstanden (Audite 95.642). Stereoplay 07|2016 (Attila Csampai - 2016.07.01) Brahms unter Strom Es ist eine der spannendsten und zwingendsten Aufführungen der Vierten von Brahms, die ich je gehört habe, noch geballter und stringenter als die berühmten Referenzen von Klemperer und Toscanini. Vor allem in den beiden Ecksätzen kombiniert Kletzki strukturelle Dichte und emotionales Feuer zu gebündelten Energieschüben, die das späte Opus fast als Fanal jugendlicher Leidenschaft und so gar nicht als abgeklärtes Alterswerk erscheinen lassen. Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. page 1 / 5 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0)5231-870320 • Fax: +49 (0)5231-870321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de www.concertonet.com 05/15/2016 (Simon Corley - 2016.05.15) Chefs oubliés: Paul Kletzki et Antonio Pedrotti Chefs oubliés: Paul Kletzki et Antonio Pedrotti Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2011 T 02

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2011 T 02 Stand: 16. Februar 2011 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2011 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT02_2011-3 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie Katalogisierung, Regeln für Musikalien und Musikton-trä- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ger (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ -

June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace

No. 495 - June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace Nothing like a Dame (make that two!) The VW’s Shakespeare party this year marked Shakespeare’s 452nd birthday as well as the 400th anniversary of his death. The party was a great success and while London, Stratford and many major cultural institutions went, in my view, a bit over-bard (sorry!), the VW’s party was graced by the presence of two Dames - Joan Plowright and Eileen Atkins, two star Shakespeare performers very much associated with the Old Vic. The party was held in the Old Vic rehearsal room where so many greats – from Ninette de Valois to Laurence Olivier – would have rehearsed. Our wonderful Vice-President, Nickolas Grace, introduced our star guests by talking about their associations with the Old Vic; he pointed out that we had two of the best St Joans ever in the room where they would have rehearsed: Eileen Atkins played St Joan for the Prospect Company at the Old Vic in 1977-8; Joan Plowright played the role for the National Theatre at the Old Vic in 1963. Nickolas also read out a letter from Ronald Pickup who had been invited to the party but was away in France. Ronald Pickup said that he often thought about how lucky he was to have six years at the National Theatre, then at Old Vic, at the beginning of his career (1966-72) and it had a huge impact on him. Dame Joan Plowright Dame Joan Plowright then regaled us with some of her memories of the Old Vic, starting with the story of how when she joined the Old Vic school in 1949 part of her ‘training’ was moving chairs in and out of the very room we were in. -

To Download the Full Archive

Complete Concerts and Recording Sessions Brighton Festival Chorus 27 Apr 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Belshazzar's Feast Walton William Walton Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Baritone Thomas Hemsley 11 May 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Kyrie in D minor, K 341 Mozart Colin Davis BBC Symphony Orchestra 27 Oct 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Budavari Te Deum Kodály Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Sarah Walker Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Brian Kay 23 Feb 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 Beethoven Herbert Menges Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Elizabeth Harwood Mezzo-Soprano Barbara Robotham Tenor Kenneth MacDonald Bass Raimund Herincx 09 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in D Dvorák Václav Smetáček Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Valerie Baulard Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 11 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Liebeslieder-Walzer Brahms Laszlo Heltay Piano Courtney Kenny Piano Roy Langridge 25 Jan 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Requiem Fauré Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Maureen Keetch Baritone Robert Bateman Organ Roy Langridge 09 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in B Minor Bach Karl Richter English Chamber Orchestra Soprano Ann Pashley Mezzo-Soprano Meriel Dickinson Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Stafford Dean Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 1 Brighton Festival Chorus 17 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra in C minor Beethoven Symphony No. -

Sir Hamilton Harty Music Collection

MS14 Harty Collection About the collection: This is a collection of holograph manuscripts of the composer and conductor, Sir Hamilton Harty (1879-1941) featuring full and part scores to a range of orchestral and choral pieces composed or arranged by Harty, c 1900-1939. Included in the collection are arrangements of Handel and Berlioz, whose performances of which Harty was most noted, and autograph manuscripts approx. 48 original works including ‘Symphony in D (Irish)’ (1915), ‘The Children of Lir’ (c 1939), ‘In Ireland, A Fantasy for flute, harp and small orchestra’ and ‘Quartet in F for 2 violins, viola and ‘cello’ for which he won the Feis Ceoil prize in 1900. The collection also contains an incomplete autobiographical memoir, letters, telegrams, photographs and various typescript copies of lectures and articles by Harty on Berlioz and piano accompaniment, c 1926 – c 1936. Also included is a set of 5 scrapbooks containing cuttings from newspapers and periodicals, letters, photographs, autographs etc. by or relating to Harty. Some published material is also included: Performance Sets (Appendix1), Harty Songs (MS14/11). The Harty Collection was donated to the library by Harty’s personal secretary and intimate friend Olive Baguley in 1946. She was the executer of his possessions after his death. In 1960 she received an honorary degree from Queen’s (Master of Arts) in recognition of her commitment to Harty, his legacy, and her assignment of his belongings to the university. The original listing was compiled in various stages by Declan Plumber