Devon: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Devon Districts Procurement Strategy 2019-2022

Devon Districts Procurement Strategy 2019-2022 1 CONTENTS Introduction Background Outcomes Action Plan Contacts 2 Introduction This is the third iteration of the Devon District Procurement Strategy. The strategy sets out our vision and our priorities for the next four years to 2022 incorporating the latest government procurement legislation and initiatives. We aim to provide quality services that are responsive to the needs of our communities and deliver optimum value for money. The strategy sets out how we aim to achieve this over the longer term and includes an action plan for the forthcoming year which will be regularly reviewed and a new action plan produced each year. By taking a collaborative approach we can improve the quality of the goods, services and works which we purchase whilst still seeking to achieve value for money and make the savings necessary to support the austerity measures. The Devon Districts who will be adopting this strategy are: Exeter City Council Mid Devon District Council North Devon District Council South Hams District Council Teignbridge District Council Torridge District Council West Devon Borough Council. It is the intention of the majority of Districts that this will be the sole procurement strategy for their council. What is procurement? Procurement is concerned with securing goods, works and services. The process spans the whole cycle, from identification of needs through to the end of a service or the end of the useful life of an asset and its disposal. It is concerned with securing goods and services that best meet the needs of users and the local community in order to help achieve our key priorities. -

West Devon Green Infrastructure Framework

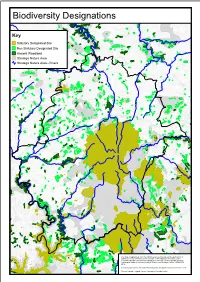

Biodiversity Designations Key Statutory Designated Site Non Statutory Designated Site Ancient Woodland Strategic Nature Area Strategic Nature Area - Rivers This map is reproduced from the Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. West Devon Borough Council. 100023302. 2014. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0. Source: Natural England, Devon Biodiversity Records Centre. Strategic Nature Areas by Habitat Type Key Upland Heath Purple Moor Grass and Rush Pasture Woodland Neutral Grassland Mudflats River This map is reproduced from the Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. West Devon Borough Council. 100023302. 2014. Source: Devon Biodiversity Records Centre. Landscape and Heritage Designations Key World Heritage Site Dartmoor National Park Tamar Valley AONB Scheduled Monument Registered Park & Garden Listed Building This map is reproduced from the Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. -

Annual Report 2010-2011

Incorporating community services in Exeter, East and Mid Devon AAnnualnnual RReporteport 2010 - 2011 Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust 2 CContentsontents Introduction . 3 Trust background . 4 Our area . 7 Our community . 7 Transforming Community Services (TCS) . 7 Our values . 7 Our vision . 7 Patient experience . 9 What you thought in 2010-11 . 10 Telling us what you think . .12 Investment in services for patients . 13 Keeping patients informed . 15 Outpatient reminder scheme launched in April 2011 . 15 Involving patients and the public in improving services . 16 Patient Safety . .17 Safe care in a safe environment . .18 Doing the rounds . 18 Preventing infections . 18 Norovirus . 18 A learning culture . 19 High ratings from staff . .20 Performance . 21 Value for money . 22 Accountability . 22 Keeping waiting times down . 22 Meeting the latest standards . 22 Customer relations . 23 Effective training and induction . .24 Dealing with violence and aggression . 24 Operating and Financial Review . 25 Statement of Internal Control . 39 Remuneration report . .46 Head of Intenal Audit opinion . 50 Accounts . 56 Annual Report 2010 - 11 3 IIntroductionntroduction Running a complex organisation is about ensuring that standards are maintained and improved at the everyday level while taking the right decisions for the longer term. The key in both hospital and community-based services is to safeguard the quality of care and treatment for patients. That underpins everything we do. And as this report shows, there were some real advances last year. For example, our new service for people with wet, age-related macular degeneration (WAMD) – a common cause of blindness – was recognised as among the best in the South West. -

West of Exeter Route Resilience Study Summer 2014

West of Exeter Route Resilience Study Summer 2014 Photo: Colin J Marsden Contents Summer 2014 Network Rail – West of Exeter Route Resilience Study 02 1. Executive summary 03 2. Introduction 06 3. Remit 07 4. Background 09 5. Threats 11 6. Options 15 7. Financial and economic appraisal 29 8. Summary 34 9. Next steps 37 Appendices A. Historical 39 B. Measures to strengthen the existing railway 42 1. Executive summary Summer 2014 Network Rail – West of Exeter Route Resilience Study 03 a. The challenge the future. A successful option must also off er value for money. The following options have been identifi ed: Diffi cult terrain inland between Exeter and Newton Abbot led Isambard Kingdom Brunel to adopt a coastal route for the South • Option 1 - The base case of continuing the current maintenance Devon Railway. The legacy is an iconic stretch of railway dependent regime on the existing route. upon a succession of vulnerable engineering structures located in Option 2 - Further strengthening the existing railway. An early an extremely challenging environment. • estimated cost of between £398 million and £659 million would Since opening in 1846 the seawall has often been damaged by be spread over four Control Periods with a series of trigger and marine erosion and overtopping, the coastal track fl ooded, and the hold points to refl ect funding availability, spend profi le and line obstructed by cliff collapses. Without an alternative route, achieved level of resilience. damage to the railway results in suspension of passenger and Option 3 (Alternative Route A)- The former London & South freight train services to the South West peninsula. -

Devon Home Choice Quarterly Monitoring Report (July 2019

Devon Home Choice Quarterly Monitoring Report (July 2019) Introduction: This report provides the latest key information from Devon Home Choice and covers the 1st April 2019 to 30st June 2019. Households registered with Devon Home Choice: The total number of households in housing need (Bands A to D) has decreased from 17,513 in April to 16,173 in July, a decrease of 8%. Even though there has been a decrease in total applications across Devon, only 5 local authorities saw a decrease in applications since April: Mid Devon, Plymouth, South Hams, Teignbridge and West Devon. The bands with highest decrease percentages are Band D and Band E, with a decrease of 7% and 10% respectively. Table 1: Number of households in housing need (Bands A to D) as at 8th July 2019 Band A Band B Band C Band D Band E No. % No. % No. % No. % Total No. % East Devon 5 0% 287 14% 677 33% 1101 53% 2,070 2,459 54% Exeter 3 0% 393 18% 626 28% 1,183 54% 2,205 1 0% Mid Devon 1 0% 106 15% 216 31% 367 53% 690 849 55% North Devon 0 0% 159 14% 301 27% 651 59% 1,111 1,202 52% Plymouth 7 0% 921 15% 1,721 28% 3,497 57% 6,146 3,512 36% South Hams 0 0% 151 22% 166 24% 370 54% 687 765 53% Teignbridge 2 0% 218 22% 385 39% 393 39% 998 0 0% Torbay 5 0% 170 15% 338 29% 644 56% 1,157 1 0% Torridge 1 0% 132 20% 220 33% 321 48% 674 472 41% West Devon 0 0% 77 18% 133 31% 225 52% 435 435 50% Total 24 0% 2,614 16% 4,783 30% 8,752 54% 16,173 9,696 37% April 2019 27 0% 2,888 16% 5,211 30% 9,390 54% 17,516 10,744 38% Note: The percentages given for Bands A – D refer to the proportion of households in housing need who are in that Band (e.g. -

Statement of Intent

Energy Company Obligation: Help to Heat Local Authority Flexible Eligibility Statement of Intent Local authority: West Devon Borough Council and South Hams District Council Date of publication: 14 December 2017 Version: 2 URL: https://www.westdevon.gov.uk/article/4188/Reducing-Fuel-Bills https://www.southhams.gov.uk/article/4187/Reducing-Fuel-Bills 1. Introduction West Devon Borough Council and South Hams District Council welcomes the introduction of Flexible Eligibility (FE) and intends to utilise it for the purposes of reducing fuel poverty in the borough. South Hams West Devon Regional Average 12.2% Number of households 5113 3622 Percentage of households 13.2% 15.2% (Government statistics) Fuel poverty is more prevalent in groups with low household incomes, including pensioners, benefit recipient, and working families with below average incomes. Fuel poverty is highest and has increased fastest, in the most deprived areas. The low wage economy, particularly in West Devon and higher living costs contribute further to levels of fuel poverty. The council runs a number a loan schemes, as well as being a part of Devon-wide schemes and initiatives to tackle fuel poverty and improve housing conditions for those who are particularly vulnerable to the cold in the private sector. One of the primary objectives of Environmental Health is to remedy category 1 hazards, excess cold being one which is particularly focused on and is the result of lack of heating and insulation. West Devon Borough Council and South Hams District Council will take advantage of this new Flexible Eligibility scheme so that as many residents can benefit as possible, and so that those who don’t qualify through existing schemes but are in fuel poverty can obtain financial help to install key energy measures. -

Plymouth and South West Devon Joint Local Plan Adoption Statement

Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 (as Amended) Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012 (as Amended) (Regulation 26) Plymouth and South West Devon Joint Local Plan Adoption Statement Notice is hereby given that the Plymouth and South West Devon Joint Local Plan has been adopted in accordance with the above regulations. It was adopted by South Hams District Council on 21 March 2019, Plymouth City Council on 26 March 2019 and West Devon Borough Council on 26 March 2019. The adopted Local Plan covers the administrative areas of Plymouth City, South Hams District and West Devon Borough and forms part of the Development Plan for these areas. The Plymouth and South West Devon Joint Local Plan has been subject to examination by two independent Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State. It incorporates the Main Modifications recommended by the Inspectors (as set out in the Appendix of their report) and Additional Modifications proposed by the Councils (detailed in a separate schedule). These documents are available on the Councils’ website: https://www.plymouth.gov.uk/plymouthandsouthwestdevonjointlocalplan/plymouthandsouthwest devo njointlocalplanadoption Any person who is aggrieved by the adoption of the Plymouth and South West Devon Joint Local Plan may make an application to the High Court under Section 113 of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 on the grounds that: • The document is not within the appropriate power; or • A procedural requirement has not been complied with. Any application to the High Court must be made no later than the end of the six week period from the final date of adoption (i.e. -

March 2020) There Are 495 European Electors

Disclosure Log West Devon Mar 2020 Ref Subject Area Request Response Response Date 1. What is the name of your local authority? 2. How many reports of discarded needles has your local 1. West Devon Borough Council. authority had in 2016/17, 2017/18 & 2018/19? 2. We do not have formal records of the number of discarded 3. If possible, please provide examples of public places where needles. 1312776 Environment these discarded needles in Q2 were found. 3. They have been found in public toilets (predominantly) and 02/03/2020 4. How many call outs for drug related litter has your local drains. All needle finds are dealt with immediately. authority had in 2016/17, 2017/18 & 2018/19? 4. We do not hold this information. 5. How many items of 'drugs related litter' were discovered by 5. We do not hold this information. your local authority in 2016/17, 2017/18 & 2018/19? Could you please provide me with a list of all public screening 1324540 Environment There are currently NIL events planned. 03/03/2020 events that the council are planning for Euro 2020 games. Please could you provide the all job roles/titles and the salary Human associated with each role for employees working in the waste & The waste and recycling services are out on contract, and the 1333471 Resources and recycling services and the housing sector. Alongside this please can Council transferred its housing stock in 1999. We therefore do not 03/03/2020 Payroll you provide the headcount per job role/title. have in-house services for these functions. -

Devon Formularies Interface Groups Annual Report 2015

Northern, Eastern and Western Devon Clinical Commissioning Group South Devon and Torbay Clinical Commissioning Group Devon Formularies Interface Groups Annual Report 2015 - 2016 North and East Devon Formulary Interface Group South and West Devon Formulary Interface Group Annual Report April 2015 – March 2016 Section Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Formulary Interface Group (FIG) members for 2015 - 2016 4 3. Addition to the FIG decision making process 6 4. Developing the formularies 7 5. Reviewing the formularies 7 6. NICE Guidance 9 7. Clinical Policy Committee 11 8. Drug applications 11 9. Website and App 13 10. Survey of users 15 2 1. Introduction This report aims to highlight the headlines of the work undertaken by the two Formulary Interface Groups for April 2015 – March 2016. The aim of the Devon Formularies is to promote prescribing which is safe, clinically appropriate and cost-effective in both primary and secondary care, providing guidance on locally recommended drug choices. In compiling the formularies consideration is given to aspects of safety, appropriateness and cost effectiveness. There will be instances where prescribing outside of the formularies will be both necessary and appropriate. The formularies are not restrictive lists but recommendations drawn up after widespread consultation amongst prescribers locally and the NHS trusts involved. The formularies are delivered through the Formulary Interface groups (FIGs) which reflect natural healthcare communities clustered around the major hospitals in Devon. After the successful merger into two formularies from the four which had served the Devon health communities prior to the NHS restructure bought about by the Health and Social Care act 2012, the Devon Formularies have continued to develop, working within a common framework. -

Devon Foster Carers' Association

DEVON FOSTER CARERS’ ASSOCIATION THE KIDS WERE EGG’STATIC ABOUT OUR EASTER EGG HUNT! (See wot we did there? ) And here are some pics to prove it….. DEVON FOSTER CARERS’ ASSOCIATION FABULOUS DAY – thanks to Denise Lacey, Kim St. Barbe and Steve Lacey for all their organising. Looking forward to the next one already! (No pressure) COUNTYWIDE NEWS DON’T MISS ANOTHER FUN DAY OUT!! (courtesy of our very own Fostering Service – thank you very much) At WILDWOOD ESCOT, Escot Park, Ottery St Mary, Devon, EX11 1LU (check out http://www.wildwoodescot.org/ for more details) On 14th April Don’t forget bring a picnic, and please confirm numbers to Karl Newton (via our Facebook page) DEVON FOSTER CARERS’ ASSOCIATION REMINDERS Foster Care Fortnight Is almost upon us again 14th – 27th May, this year. If you have any ideas that could help us celebrate it, please let us hear them, via the usual mechanisms, (i.e. our FB page, or email to any of the Committee - (i.e. Trish Bagshaw, Leigh Strange, Lewis Crowden, Mike Gillard, Glyn Oliver Denise Lacey, David Leyland, or Andrew Randall) TO ALL NEW CARERS, DON’T FORGET… …your MAX Card offers all foster carers If you’d like to be part of our Facebook page discounts to a variety of entertainment (where you can meet other carers in your venues. If you haven’t received yours yet, area and access a wide range of information, speak to your SSW asap, so you and your guidance and knowledge from others children carers), just send any one of us a ‘friend DON’T MISS OUT! request’ and (after checking you are who For more information about what’s on offer you say you are) we’ll add you to our closed check out… http://www.mymaxcard.co.uk/ group. -

CFS/ME Supporting Services Information

PATIENT INFORMATION CFS/ME Supporting Services Information Website: http://tsdft.uk/cfsme Or https://www.torbayandsouthdevon.nhs.uk/cfsme Working with you, for you CFS/ME Service - Torbay NHS Website Please see our video and other resources on our trust website We have our relaxations available, to listen to or download via the Torbay and South Devon Trust Website; please enter the link below to gain direct access. https://tsdft.uk/cfsme or https://www.torbayandsouthdevon.nhs.uk/cfsme CFS/ME CHARITIES FIBROMYALGIA Action for ME (AFME) Fibromyalgia Association Open Mon-Fri 10am-4pm UK Tel: 0117 927 9551 Website: www.fmauk.org/ Select option 6 Fibromyalgia Association UK or Email at any time: is a registered charity run [email protected]. primarily by unpaid uk volunteers. The majority of or Write to: volunteers are also Action for M.E. fibromyalgia sufferers who 42 Temple Street work extremely hard, despite Keynsham their condition, in order to BS31 1EH forward the cause of fibromyalgia. FMA UK was Website: established in order to https://www.actionforme.org. provide information and uk/contact/ support to sufferers and their For all information on CFS/ families. In addition, the ME related issues. Association provides medical Information and sign posting information for professionals to NHS Services, local and operates a national support groups, information helpline. and resources about the illness. ME Association support line Website: http://www.meassociation.or g.uk/information-and- support-line/ ME connect helpline available: Mornings 10-12 midday Afternoons 2-4pm Evenings 7-9pm Tel: 0844 5765326 (can be expensive on mobiles) SOCIAL NEEDS & They hold a wide range of INDEPENDENT LIVING information for families in Torbay who are either Social Services accessing our services or looking for available groups, Torbay, Paignton, events, activities, advice and Brixham: other support available Tel: 01803 219 700 COUNSELLING Devon (covering Teignbridge and South Ask your GP about local Hams): counselling services. -

The Local Government Boundary Commission for England Electoral Review of Mid Devon

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF MID DEVON Final recommendations for ward boundaries in the district of Mid Devon January 2021 Sheet 1 of 1 MOREBATH CP Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. CLAYHANGER CP This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2020. OAKFORD CP BAMPTON CP KEY TO PARISH WARDS CREDITON CP A BONIFACE CLARE & B LAWRENCE SHUTTERN HOCKWORTHY CP CULLOMPTON CP HUNTSHAM CP C PADBROOK STOODLEIGH CP HOLCOMBE D ST ANDREWS ROGUS CP E VALE TIVERTON CP CANONSLEIGH F CASTLE G COVE G H CRANMORE I LOWMAN WASHFIELD CP J WESTEXE UPLOWMAN CP SAMPFORD BURLESCOMBE CP TIVERTON PEVERELL CP LOWMAN LOXBEARE CP CULMSTOCK CP TEMPLETON CP I UPPER CLAYHIDON CP F CULM HEMYOCK CP TIVERTON THELBRIDGE CP TIVERTON WESTEXE CASTLE H TIVERTON CP J CHAWLEIGH CP CRUWYS TIVERTON HALBERTON CP UFFCULME CP WEMBWORTHY CP MORCHARD CP CRANMORE TAW VALE PUDDINGTON HALBERTON WASHFORD CP PYNE CP WILLAND CP LOWER WAY CULM EGGESFORD CP LAPFORD CP WOOLFARDISWORTHY CP KENTISBEARE CP POUGHILL CP CADELEIGH CP BUTTERLEIGH CP CULLOMPTON ST NYMET ANDREWS D BRUSHFORD CP ROWLAND CP C KENNERLEIGH CP MORCHARD BISHOP CP CULLOMPTON STOCKLEIGH