Large Whales of the Bay of Biscay and Whale Strike Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic

water Review Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic Valentina S. Artamonova 1, Ivan N. Bolotov 2,3,4, Maxim V. Vinarski 4 and Alexander A. Makhrov 1,4,* 1 A. N. Severtzov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, 119071 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Molecular Ecology and Phylogenetics, Northern Arctic Federal University, 163002 Arkhangelsk, Russia; [email protected] 3 Federal Center for Integrated Arctic Research, Russian Academy of Sciences, 163000 Arkhangelsk, Russia 4 Laboratory of Macroecology & Biogeography of Invertebrates, Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Analysis of zoogeographic, paleogeographic, and molecular data has shown that the ancestors of many fresh- and brackish-water cold-tolerant hydrobionts of the Mediterranean region and the Danube River basin likely originated in East Asia or Central Asia. The fish genera Gasterosteus, Hucho, Oxynoemacheilus, Salmo, and Schizothorax are examples of these groups among vertebrates, and the genera Magnibursatus (Trematoda), Margaritifera, Potomida, Microcondylaea, Leguminaia, Unio (Mollusca), and Phagocata (Planaria), among invertebrates. There is reason to believe that their ancestors spread to Europe through the Paratethys (or the proto-Paratethys basin that preceded it), where intense speciation took place and new genera of aquatic organisms arose. Some of the forms that originated in the Paratethys colonized the Mediterranean, and overwhelming data indicate that Citation: Artamonova, V.S.; Bolotov, representatives of the genera Salmo, Caspiomyzon, and Ecrobia migrated during the Miocene from I.N.; Vinarski, M.V.; Makhrov, A.A. -

Suspended Sediment Delivery from Small Catchments to the Bay of Biscay. What Are the Controlling Factors ?

Open Archive TOULOUSE Archive Ouverte (OATAO) OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and makes it freely available over the web where possible. This is an author-deposited version published in : http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/ Eprints ID : 16604 To link to this article : DOI : 10.1002/esp.3957 URL : http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/esp.3957 To cite this version : Zabaleta, Ane and Antiguedad, Inaki and Barrio, Irantzu and Probst, Jean-Luc Suspended sediment delivery from small catchments to the Bay of Biscay. What are the controlling factors ? (2016) Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, vol.41, n°13, pp. 1813-2004. ISSN 1096-9837 Any correspondence concerning this service should be sent to the repository administrator: [email protected] Suspended sediment delivery from small catchments to the Bay of Biscay. What are the controlling factors? Ane Zabaleta,1* liiaki Antiguedad,1 lrantzu Barrio2 and Jean-Luc Probst3 1 Hydrology and Environment Group, Science and Technology Faculty, University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, Leioa, Basque Country, Spain 2 Department of Applied Mathematics, Statistics and Operations Research, Science and Technology Faculty, University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, Leioa, Basque Country, Spain 3 EcoLab, University of Toulouse, CNRS, INPT, UPS, Toulouse, France *Correspondence to: Ane Zabaleta, Hydrology and Environment Group, Science and Technology Faculty, University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU, 48940 Leioa, Basque Country, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The transport and yield of suspended sediment (SS) in catchments all over the world have long been tapies of great interest. -

~Ertif Ied by 3 0 7 Thesis S Uperv Isg.Rn.:T::.··__....---

1 A GRAPHIC DISPLAY OF PLATE TECTONICS IN THE TETHYS SEA by Anthony B. Williams S.B. California Institute of Technology (1965) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE 3.EQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF ·rECHNOLOGY August, 1971 ignature of Author Signature redacted Department oj;t=Earth and Planetary Science _S_ig_n_a_tu_r_e_r_e_d_a_c_te_d__ ~ ,_, , ~ertif ied by 3 0 7 Thesis S uperv isg.rn.:t::.··__....--- .. Signature redacted ccepted by Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 MITLibraries http://Iibraries.mit.edu/ask DISCLAIMER NOTICE Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. Thank you. Some pages in the original document contain text that runs off the edge of the page. 2 ABSTRACT The hypothesis of plate tectonics is applied to the Mediterranean Sea region in order to explain its Tertiary mountain chains and to derive previous positions for the component plate fragments. Consuming plate boundaries are selected on geophysical and geological grounds, and are assumed connected through modern oceanic regions by shearing and accreting boundaries. The resultant plate fragments are rotated to fit geological and morphological similarities, and the timing of tectonic events, without violating available constraints. The cumulative rotations are plotted to illustrate behind-arc spreading in the western Mediterranean basins and closure upon the Adriatic and Ionian seas from east and west following northward motion of the central Alpine plate fragment. I 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS -Abstract . -

Chapter 24. the BAY of BISCAY: the ENCOUNTERING of the OCEAN and the SHELF (18B,E)

Chapter 24. THE BAY OF BISCAY: THE ENCOUNTERING OF THE OCEAN AND THE SHELF (18b,E) ALICIA LAVIN, LUIS VALDES, FRANCISCO SANCHEZ, PABLO ABAUNZA Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO) ANDRE FOREST, JEAN BOUCHER, PASCAL LAZURE, ANNE-MARIE JEGOU Institut Français de Recherche pour l’Exploitation de la MER (IFREMER) Contents 1. Introduction 2. Geography of the Bay of Biscay 3. Hydrography 4. Biology of the Pelagic Ecosystem 5. Biology of Fishes and Main Fisheries 6. Changes and risks to the Bay of Biscay Marine Ecosystem 7. Concluding remarks Bibliography 1. Introduction The Bay of Biscay is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean, indenting the coast of W Europe from NW France (Offshore of Brittany) to NW Spain (Galicia). Tradition- ally the southern limit is considered to be Cape Ortegal in NW Spain, but in this contribution we follow the criterion of other authors (i.e. Sánchez and Olaso, 2004) that extends the southern limit up to Cape Finisterre, at 43∞ N latitude, in order to get a more consistent analysis of oceanographic, geomorphological and biological characteristics observed in the bay. The Bay of Biscay forms a fairly regular curve, broken on the French coast by the estuaries of the rivers (i.e. Loire and Gironde). The southeastern shore is straight and sandy whereas the Spanish coast is rugged and its northwest part is characterized by many large V-shaped coastal inlets (rias) (Evans and Prego, 2003). The area has been identified as a unit since Roman times, when it was called Sinus Aquitanicus, Sinus Cantabricus or Cantaber Oceanus. The coast has been inhabited since prehistoric times and nowadays the region supports an important population (Valdés and Lavín, 2002) with various noteworthy commercial and fishing ports (i.e. -

Submarine Warfare, Fiction Or Reality? John Charles Cheska University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1962 Submarine warfare, fiction or reality? John Charles Cheska University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Cheska, John Charles, "Submarine warfare, fiction or reality?" (1962). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1392. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1392 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. bmbb ittmtL a zia a musv John C. Chaaka, Jr. A.B. Aaharat Collag* ThMis subnlttwi to tho Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of tha requlraaanta for tha degraa of Master of Arta Uoiwaity of Maaaaohuaetta Aaherat August, 1962 a 3, v TABU OF CONTENTS Hm ramp _, 4 CHAPTER I Command Structure and Policy 1 II Material III Operations 28 I? The Submarine War ae the Public Saw It V The Number of U-Boate Actually Sunk V VI Conclusion 69 APPENDXEJB APPENDIX 1 Admiralty Organisation in 1941 75 2 German 0-Boat 76 3 Effects of Strategic Bombing on Late Model 78 U-Boat Productions and Operations 4 U-Boats Sunk Off the United States Coaat 79 by United States Forces 5 U-Boats Sunk in Middle American Zone 80 inr United StatM ?bkii 6 U-Bosta Sunk Off South America 81 by United States Forces 7 U-Boats Sunk in the Atlantio in Area A 82 1 U-Boats Sunk in the Atlentio in Area B 84 9A U-Boats Sunk Off European Coast 87 by United States Forces 9B U-Bnata Sunk in Mediterranean Sea by United 87 States Forces TABLE OF CONTENTS klWDU p«g« 10 U-Boats Sunk by Strategic Bombing 38 by United States Amy Air Foreee 11 U-Boats Sunk by United States Forces in 90 Cooperation with other Nationalities 12 Bibliography 91 LIST OF MAPS AND GRAPHS MAP NO. -

Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast Ecoregion Published 10 December 2020

ICES Ecosystem Overviews Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast ecoregion Published 10 December 2020 6.1 Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast ecoregion – Ecosystem Overview Table of contents Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast ecoregion – Ecosystem Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Ecoregion description ................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Key signals within the environment and the ecosystem .............................................................................................................................. 2 Pressures ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Climate change impacts ................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 State of the ecosystem ................................................................................................................................................................................. 9 Sources and acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................................ 14 Sources -

Marine Litter in Submarine Canyons of the Bay of Biscay

1 Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography Achimer November 2017, Volume 145, Pages 142-152 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2016.04.013 http://archimer.ifremer.fr http://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00332/44363/ © 2016 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Marine litter in submarine canyons of the Bay of Biscay Van Den Beld Inge 1, * , Guillaumont Brigitte 1, Menot Lenaick 1, Bayle Christophe 1, Arnaud-Haond Sophie 1, Bourillet Jean-Francois 2 1 Ifremer, Centre de Brest, EEP/LEP, CS 10070, 29280 Plouzané, France 2 Ifremer, Centre de Brest, REM/GM, CS 10070, 29280 Plouzané, France * Corresponding author : Inge Van Den Beld, Tel.: +33 0 2 98 22 40 40; fax: +33 0 2 98 22 47 57 ; email address : [email protected] Abstract : Marine litter is a matter of increasing concern worldwide, from shallow seas to the open ocean and from beaches to the deep-seafloor. Indeed, the deep sea may be the ultimate repository of a large proportion of litter in the ocean. We used footage acquired with a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) and a towed camera to investigate the distribution and composition of litter in the submarine canyons of the Bay of Biscay. This bay contains many submarine canyons housing Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems (VMEs) such as scleractinian coral habitats. VMEs are considered to be important for fish and they increase the local biodiversity. The objectives of the study were to investigate and discuss: i) litter density, ii) the principal sources of litter, iii) the influence of environmental factors on the distribution of litter, and iv) the impact of litter on benthic communities. -

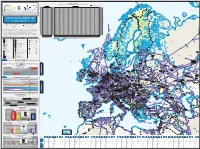

System Development Map 2019 / 2020 Presents Existing Infrastructure & Capacity from the Perspective of the Year 2020

7125/1-1 7124/3-1 SNØHVIT ASKELADD ALBATROSS 7122/6-1 7125/4-1 ALBATROSS S ASKELADD W GOLIAT 7128/4-1 Novaya Import & Transmission Capacity Zemlya 17 December 2020 (GWh/d) ALKE JAN MAYEN (Values submitted by TSO from Transparency Platform-the lowest value between the values submitted by cross border TSOs) Key DEg market area GASPOOL Den market area Net Connect Germany Barents Sea Import Capacities Cross-Border Capacities Hammerfest AZ DZ LNG LY NO RU TR AT BE BG CH CZ DEg DEn DK EE ES FI FR GR HR HU IE IT LT LU LV MD MK NL PL PT RO RS RU SE SI SK SM TR UA UK AT 0 AT 350 194 1.570 2.114 AT KILDIN N BE 477 488 965 BE 131 189 270 1.437 652 2.679 BE BG 577 577 BG 65 806 21 892 BG CH 0 CH 349 258 444 1.051 CH Pechora Sea CZ 0 CZ 2.306 400 2.706 CZ MURMAN DEg 511 2.973 3.484 DEg 129 335 34 330 932 1.760 DEg DEn 729 729 DEn 390 268 164 896 593 4 1.116 3.431 DEn MURMANSK DK 0 DK 101 23 124 DK GULYAYEV N PESCHANO-OZER EE 27 27 EE 10 168 10 EE PIRAZLOM Kolguyev POMOR ES 732 1.911 2.642 ES 165 80 245 ES Island Murmansk FI 220 220 FI 40 - FI FR 809 590 1.399 FR 850 100 609 224 1.783 FR GR 350 205 49 604 GR 118 118 GR BELUZEY HR 77 77 HR 77 54 131 HR Pomoriy SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT MAP HU 517 517 HU 153 49 50 129 517 381 HU Strait IE 0 IE 385 385 IE Kanin Peninsula IT 1.138 601 420 2.159 IT 1.150 640 291 22 2.103 IT TO TO LT 122 325 447 LT 65 65 LT 2019 / 2020 LU 0 LU 49 24 73 LU Kola Peninsula LV 63 63 LV 68 68 LV MD 0 MD 16 16 MD AASTA HANSTEEN Kandalaksha Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 MK 0 MK 20 20 MK 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM NL 418 963 1.381 NL 393 348 245 168 1.154 NL T +32 2 894 51 00 T +32 2 209 05 00 PL 158 1.336 1.494 PL 28 234 262 PL Twitter @ENTSOG Twitter @GIEBrussels PT 200 200 PT 144 144 PT [email protected] [email protected] RO 1.114 RO 148 77 RO www.entsog.eu www.gie.eu 1.114 225 RS 0 RS 174 142 316 RS The System Development Map 2019 / 2020 presents existing infrastructure & capacity from the perspective of the year 2020. -

Bay of Biscay by Global Ocean Associates Prepared for Office of Naval Research – Code 322 PO

An Atlas of Oceanic Internal Solitary Waves (February 2004) Bay of Biscay by Global Ocean Associates Prepared for Office of Naval Research – Code 322 PO Bay of Biscay Overview The Bay of Biscay is located in the northeast Atlantic Ocean and is bounded by the western coast of France and the northern coast of Spain (Figure 1). The Bay is characterized by a broad and irregular continental shelf. Figure 1. Bathymetry of the Bay of Biscay. [Smith and Sandwell, 1997] 57 An Atlas of Oceanic Internal Solitary Waves (February 2004) Bay of Biscay by Global Ocean Associates Prepared for Office of Naval Research – Code 322 PO Observations There has been considerable study on internal waves in the Bay of Biscay; both those that occur along the continental shelf break and those in the central Bay approximately 120 to 150 km from the shelf edge. The shelf break internal waves have been well characterized by Pingree and Mardell [1985] and Pingree et al. [1986] with amplitudes (peak to trough) of up to 40 m. The internal waves at the shelf break produce complex surface pattern, due to varying topography and irregular edge of the shelf break in the northern Bay. New and Pingree [1990, 1992] and New and daSilva [2002] have investigated internal waves in the Central Bay. These waves, with amplitudes of up to 80 m, are thought to be locally generated [New and Pingree 1990] through a reflection of tidal energy that re-emerges at the surface near where internal waves have been observed in the central Bay. Like other sites in the north Atlantic, (New York Bight, Northwest Africa) both types of internal waves in the Bay are believed to occur only during the summer and early fall (June though September) when a well-developed thermocline is present (Table 1). -

Gaviota Storage Facility Is Located in the Bay of Biscay, 8 Km

The natural gas chain Impreso en papel ecológico y libre de cloro. More than 90 years of underground storage facilities Natural gas’s long journey from the gas elds to the end consumer The Gaviota storage facility is located in the Bay of Biscay, 8 Km. off Cape Matxitxako, north east of Bermeo (Biscay). Extraction NG transport The storage facility is in a depleted gas eld covering The Gaviota storage facility is accessed from a platform 2 The gas is extracted from the The natural gas (NG) is transported a surface area of 64 km . It is located at a depth of anchored to the seabed with 20 pylons and connected gas elds using drilling wells and through gas pipelines 2,150 m in fractured limestone from the Upper by a gas pipeline to an onshore processing plant. extraction pipes Cretaceous. Liquefaction The NG is liquefi ed (LNG) to reduce its volume and make it easier to transport Gaviota Platform Gas processing plant LNG transportation The liquid natural gas Bermeo is transported in methane tankers to regasi cation plants Bilbao Regasi cation The liquid gas is returned to its original gaseous state in regasi cation plants NG transport Distribution to Natural gas is transported end consumers through the high-pressure network Gaviota Bilbao A system that copies nature Underground storage Serrablo Gaviota Castor Yela Gas has been stored naturally for millions Marismas of years. Palancares Underground natural gas Poseidón This process has been copied in Gaviota, with a depleted gas eld being used as an storage facility underground storage facility. -

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS in the BAY of BISCAY and IBERIAN COASTS DATABASE COMPLETION and ANALYSIS January 2019 Version 2

MARINE PROTECTED AREAS IN THE BAY OF BISCAY AND IBERIAN COASTS DATABASE COMPLETION AND ANALYSIS January 2019 Version 2 Supporting Implementation of Maritime Spatial Planning in the Northern European Atlantic European Commission Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Grant Agreement No. EASME/EMFF/2015/1.2.1.3/03/SI2.742089-SIMNORAT Component 1.3.2 – Spatial demands and future trends for maritime sectors and marine conservation Deliverable Lead Partner: Agence Française pour la Biodiversité Start date of the project: 01/01/2017 Duration: 25 months Version: 1.1 Contributors (in alphabetical order): Alloncle Neil, AFB; Bliard Fanny, AFB; Campillos-Llanos Mónica, IEO; Cervera-Núñez Cristina, IEO; De Magalhães Ana Vitoria, AFB; Fauveau Guillaume, AFB; Gimard Antonin, AFB; Giret Olivier, CEREMA; Gómez-Ballesteros María, IEO; Lloret Ana, CEDEX; Lopes Alves Fátima, UAVR; Mahier Marie, AFB; Marques Márcia, UAVR; Murciano Carla, CEDEX; Odion Mélanie, AFB; Piel Steven, AFB; Quintela Adriano, UAVR; Sousa Lisa, UAVR. Dissemination level PU Public PP Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission services) RE Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (Including the Commission services) Disclaimer: This report was produced as part of the SIMNORAT Project (Grant Agreement N0. EASME/EMFF/2015/1.2.1.3/03/SI2.742089). The contents and conclusions of this report, including the maps and figures were developed by the participating partners with the best available knowledge at the time. They do not necessarily reflect the national governments’ positions and are not official documents, nor data. The European Commission or Executive Agency for Small and Medium sized Enterprises is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. -

Case Concerning Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in the Gulf of Maine Area (Canada/United States of America)

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE PLEADl NGS, ORAL ARGUMENTS, DOCUMENTS CASE CONCERNING DELIMITATION OF THE MARITIME BOUNDARY IN THE GULF OF MAINE AREA (CANADA/UNITED STATES OF AMERICA) VOLUME VllI Maps, Charts and lllustrations COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE MÉMOIRES,PLAIDOIRIES ET DOCUMENTS AFFAIRE DE LA DÉLIMITATION DE-LA FRONTIÈRE MARITIME DANS LA RÉGION DU GOLFE DU MAINE VOLUME VI11 Cartes et illustrations INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE PLEADINGS, ORAL ARGUMENTS, DOCUMENTS CASE CONCERNING DELIMITATION OF THE MARITIME BOUNDARY IN THE GULF OF MAINE AREA (CANADAIUNITED STATES OF AMERICA) VOLUME VI11 Maps, Charts and Illustrations COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE MÉMOIRES. PLAIDOIRIES ET DOCUMENTS AFFAIRE DE LA DÉLIMITATION DE LA FRONTIÈRE MARITIME DANS LA RÉGION DU GOLFE DU MAINE VOLUME VI11 Cartes et illustrations TABLE OF MAPS, CHARTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS This Table lists the mans. charts and illustrations in the order of their amear- ance within the written prhceedings. In the margin, the ringed numerais cor- respond to the numherina of the maps, charts and illustrations reproduced in this Volume. The ahsenci of anv rineed numeral or reference to a Volume of ihir çdiiion signil'ies that ihç ill;rtracon in quertion has no1 heen reproduced 'lhe 'lïhle also lists. with sirnilx indicïtions. the maps ïnd charts deposited durine the oral nroceedines which have been renroduced in this Volume. It dues no[. huwci,ér. list the kaPr and charts u,ed during the hcdring which had already ïppeared in the written procccdings or hai,e no1 hcen reproduced in thi>ediiion, for \ihich ihç reader should iurn ta ihe ieni of the oral arguments or to the correspondence (Vols.