Treatment of Infants with Syndromic Robin Sequence with Modified

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly

277 Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly KellenD.Winden,MD,PhD1 Christopher J. Yuskaitis, MD, PhD1 Annapurna Poduri, MD, MPH2 1 Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Address for correspondence Annapurna Poduri, Epilepsy Genetics Massachusetts Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Electrophysiology, 2 Epilepsy Genetics Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Department of Neurology, Fegan 9, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Electrophysiology, Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (e-mail: [email protected]). Semin Neurol 2015;35:277–287. Abstract Megalencephaly is a developmental disorder characterized by brain overgrowth secondary to increased size and/or numbers of neurons and glia. These disorders can be divided into metabolic and developmental categories based on their molecular etiologies. Metabolic megalencephalies are mostly caused by genetic defects in cellular metabolism, whereas developmental megalencephalies have recently been shown to be caused by alterations in signaling pathways that regulate neuronal replication, growth, and migration. These disorders often lead to epilepsy, developmental disabilities, and Keywords behavioral problems; specific disorders have associations with overgrowth or abnor- ► megalencephaly malities in other tissues. The molecular underpinnings of many of these disorders are ► hemimegalencephaly now understood, providing insight into how dysregulation of critical pathways leads to ► -

The First Non-Invasive Prenatal Test That Screens for Single-Gene Disorders

The first non-invasive prenatal test that screens for single-gene disorders the evolution of NIPT A non-invasive prenatal test that screens multiple genes for mutations causing severe genetic disorders in the fetus analyses circulating cell- free fetal DNA (cfDNA) from a maternal blood sample. The test is performed after 10 weeks of pregnancy. works as a complementary screen to traditional and genome- wide NIPT . It screens for several life-altering genetic disorders that are not screened with current NIPT technology, allowing a complete picture of the risk of a pregnancy being affected by a genetic disorder. 2 facilitates early diagnosis of single-gene disorders. It involves 3 different levels of screening: This test screens for 5 common inherited recessive genetic disorders, such as Cystic Fibrosis, Beta-Thalassemia, Sickle INHERITED cell anaemia, Deafness autosomal recessive type 1A, Deafness autosomal recessive type 1B. Genes screened: CFTR, CX26 (GJB2), CX30 (GJB6), HBB This test screens for 44 severe genetic disorders due to de novo mutations (a gene mutation that is not inherited) in 25 genes DE NOVO Genes screened: ASXL1, BRAF, CBL, CHD7, COL1A1, COL1A2 , COL2A1, FGFR2, FGFR3, HDAC8, JAG1, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAP2K2, MECP2, NIPBL, NRAS, NSD1, PTPN11, RAF1, RIT1, SETBP1, SHOC2, SIX3, SOS1 This test screens for both inherited and de novo single-gene disorders and represents a combination of the tests INHERITED COMPLETE and DE NOVO providing a complete picture of the pregnancy risk. 3 allows detection of common inherited genetic disorders in INHERITED the fetus GENE GENETIC DISORDER CFTR Cystic Fibrosis CX26 (GJB2) Deafness autosomal recessive type 1A CX30 (GJB6) Deafness autosomal recessive type 1B HBB Beta-Thalassemia HBB Sickle cell anemia The inherited recessive disorders screened by INHERITED are the most common in the European population 4 identifies fetal conditions that could be missed by traditional DE NOVO prenatal screening. -

Metacarpophalangeal Pattern Profile Analysis in Sotos Syndrome

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE HHS Public Access provided by IUPUIScholarWorks Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Am J Med Manuscript Author Genet. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 September 12. Published in final edited form as: Am J Med Genet. 1985 April ; 20(4): 625–629. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320200408. Metacarpophalangeal Pattern Profile Analysis in Sotos Syndrome Merlin G. Butler, Department of Biology, University of Notre Dame and North Central Regional Genetics Center, Memorial Hospital, South Bend, Indiana Department of Medical Genetics, Indiana University School of Medicine F. John Meaney, Department of Medical Genetics, Indiana University School of Medicine Genetic Diseases Section, Indiana State Board of Health, Indianapolis Smita Kittur, Pediatric Genetics Department, Children’s Medical and Surgical Center, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore Joseph H. Hersh, and Child Evaluation Center, Department of Pediatrics, University of Louisville School of Medicine Lusia Hornstein Cincinnati Center for Developmental Disorders, Children’s Hospital Medical Center Abstract The metacarpophalangeal pattern profile (MCPP) was analyzed on 16 Sotos syndrome patients. A mean Sotos syndrome profile was produced. Correlation studies confirm clinical homogeneity of Sotos syndrome individuals. Discriminant analysis of Sotos syndrome patients and normal individuals produces a function of two MCPP variables and age, which may provide a useful tool for diagnosis. Keywords Sotos syndrome; metacarpophalangeal pattern profile (MCPP); discriminant analysis; correlation studies INTRODUCTION Sotos syndrome, or cerebral gigantism, was first described by Sotos et al [1964]; at least 100 cases were reported subsequently. This syndrome is characterized by large size at birth, large hands and feet, advanced osseous maturation, macrocephaly with prominent forehead and Address reprint requests to Merlin G. -

Diagnostic Utility of Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis in Mendelian Neurodevelopmental Disorders

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Diagnostic Utility of Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis in Mendelian Neurodevelopmental Disorders Sadegheh Haghshenas 1,2 , Pratibha Bhai 2, Erfan Aref-Eshghi 3 and Bekim Sadikovic 1,2,4,* 1 Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Western University, London, ON N6A 3K7, Canada; [email protected] 2 Molecular Genetics Laboratory, Molecular Diagnostics Division, London Health Sciences Centre, London, ON N6A 5W9, Canada; [email protected] 3 Division of Genomic Diagnostics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; [email protected] 4 Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, ON N6A 5C1, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 22 November 2020; Accepted: 4 December 2020; Published: 6 December 2020 Abstract: Mendelian neurodevelopmental disorders customarily present with complex and overlapping symptoms, complicating the clinical diagnosis. Individuals with a growing number of the so-called rare disorders exhibit unique, disorder-specific DNA methylation patterns, consequent to the underlying gene defects. Besides providing insights to the pathophysiology and molecular biology of these disorders, we can use these epigenetic patterns as functional biomarkers for the screening and diagnosis of these conditions. This review summarizes our current understanding of DNA methylation episignatures in rare disorders and describes the underlying technology and analytical approaches. We discuss the computational parameters, including statistical and machine learning methods, used for the screening and classification of genetic variants of uncertain clinical significance. Describing the rationale and principles applied to the specific computational models that are used to develop and adapt the DNA methylation episignatures for the diagnosis of rare disorders, we highlight the opportunities and challenges in this emerging branch of diagnostic medicine. -

Regional Genetic Consultation Service

Regional Genetic Consultation Service Contract 5889BD01 July 1, 2018 through June 30, 2019 Congenital & Inherited Disorders Division of Health Promotion & Chronic Disease Prevention, Phone: 1-800-383-3826 http://idph.iowa.gov/genetics Regional Genetic Consultation Service: A contract established by IDPH in the Division of Health Promotion & Chronic Disease Prevention, Contract # 5888BD01 Administrative Code, Chapter 4:641-4.5(136A) Iowa Department of Public Health Advancing Health Through the Generations Kimberly Reynolds Adam Gregg Gerd Clabaugh Governor Lt. Governor Director Authorized State Official for this contract: Brenda Dobson, Director, Division of Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention (515) 281-7769 University of Iowa Stead Family Department of Pediatrics (319) 356-2675 Hatem El-Shanti, MD, Division Director John A. Bernat, MD, PhD, Clinical Director Hannah Bombei, MS, CGC, Program Coordinator Page | 2 Congenital & Inherited Disorders Division of Health Promotion & Chronic Disease Prevention, Phone: 800-383-3826 http://idph.iowa.gov/genetics In collaboration with the Iowa Department of Public Health & The Stead Family Department of Pediatrics Division of Medical Genetics & Genomics University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital & Clinical Outreach Services University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Page | 3 What is the Regional Genetic Consultation Service? Iowa Administrative Code 641—4.5(136A) Regional Genetic Consultation Service (RGCS). This program provides comprehensive genetic and genomic services statewide through outreach clinics. 4.5(1) Provision of comprehensive genetic and genomic services. The department shall contract with the Division of Medical Genetics & Genomics within the Stead Family Department of Pediatrics at the University of Iowa to provide genetic and genomic health care and education outreach services for individuals and families within Iowa. -

Abstracts Books 2014

TWENTY-FIFTH EUROPEAN MEETING ON DYSMORPHOLOGY 10 – 12 SEPTEMBER 2014 25th EUROPEAN MEETING ON DYSMORPHOLOGY LE BISCHENBERG WEDNESDAY 10th SEPTEMBER 5 p.m. to 7.30 p.m. Registration 7.30 p.m. to 8.30 p.m. Welcome reception 8.30 p.m. Dinner 9.30 p.m. Unknown THURSDAY 11th SEPTEMBER 8.15 a.m. Opening address 8.30 a.m. to 1.00 p.m. First session 1.00 p.m. Lunch 2.30 p.m. to 7.00 p.m. Second and third sessions 8.00 p.m. Dinner 9.00 p.m. to 11.00 p.m. Unknown FRIDAY 12th SEPTEMBER 8.30 a.m. to 1.00 p.m. Fourth and fifth sessions 1.00 p.m. Lunch 2.30 p.m. to 6.00 p.m. Sixth and seventh sessions 7.30 p.m. Dinner SATURDAY 13th SEPTEMBER Breakfast – Departure Note: This program is tentative and may be modified. WEDNESDAY 10th SEPTEMBER 9.30 UNKNOWN SESSION Chair: FRYNS J.P. H. VAN ESCH Case 1 H. VAN ESCH Case 2 H. JILANI, S. HIZEM, I. REJEB, F. DZIRI AND L. BEN JEMAA Developmental delay, dysmorphic features and hirsutism in a Tunisian girl. Cornelia de Lange syndrome? L. VAN MALDERGEM, C. CABROL, B. LOEYS, M. SALEH, Y. BERNARD, L. CHAMARD AND J. PIARD Megalophthalmos and thoracic great vessels aneurisms E. SCHAEFER AND Y. HERENGER An unknown diagnosis associating facial dysmorphism, developmental delay, posterior urethral valves and severe constipation P. RUMP AND T. VAN ESSEN What’s in the name G. MUBUNGU, A. LUMAKA, K. -

Jaw Keratocysts and Sotos Syndrome

International Journal on Oral Health Jaw Keratocysts and Sotos Syndrome Case Report Volume 1 Issue 2- 2021 Author Details Jin Fei Yeo and Philip McLoughlin* Faculty of Dentistry, National University Centre for Oral Health Singapore, Singapore *Corresponding author Philip McLoughlin, Discipline of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, National University Centre for Oral Health Singapore, 9 Lower Kent Ridge Road, Singapore Article History Received: June 05, 2021 Accepted: June 14, 2021 Published: June 15, 2021 Abstract Sotos syndrome, described by Sotos et al. [1], is characterized by excessive growth during childhood, macrocephaly, distinctive facial appearance and learning disability. The disorder is largely caused by mutations or deletions in the NSD1 gene. The typical facial gestalt includes macrodolichocephaly with frontal bossing, front-parietal sparseness of hair, apparent hypertelorism, down slanting palpebral in his jaw bones, a previously unreported oral manifestation, out with a syndromic context. fissures, and facial flushing. This paper discusses a case of Sotos syndrome in an adolescent male with multiple odontogenic keratocysts Introduction On examination, he was a generally healthy and rather active patient. He was very tall with macrocephaly, large hands and feet, and Sotos syndrome (Cerebral gigantism) is a rare genetic childhood hypertelorism with slightly down-slanted eyes. He also suffered ASD/ overgrowth condition described in 1964 by Sotos et al. [1]. This autism and mild mental hypo development with noticeable speech syndrome is characterized by excessive growth during childhood, impairment. On clinical assessment he was found to have a number of macrocephaly, distinctive facial appearance and learning disability. unerupted teeth, with fluctuant expansion of the maxilla and mandible The disorder is caused by mutations or 5q35 microdeletions in the at those sites. -

Soonerstart Automatic Qualifying Syndromes and Conditions

SoonerStart Automatic Qualifying Syndromes and Conditions - Appendix O Abetalipoproteinemia Acanthocytosis (see Abetalipoproteinemia) Accutane, Fetal Effects of (see Fetal Retinoid Syndrome) Acidemia, 2-Oxoglutaric Acidemia, Glutaric I Acidemia, Isovaleric Acidemia, Methylmalonic Acidemia, Propionic Aciduria, 3-Methylglutaconic Type II Aciduria, Argininosuccinic Acoustic-Cervico-Oculo Syndrome (see Cervico-Oculo-Acoustic Syndrome) Acrocephalopolysyndactyly Type II Acrocephalosyndactyly Type I Acrodysostosis Acrofacial Dysostosis, Nager Type Adams-Oliver Syndrome (see Limb and Scalp Defects, Adams-Oliver Type) Adrenoleukodystrophy, Neonatal (see Cerebro-Hepato-Renal Syndrome) Aglossia Congenita (see Hypoglossia-Hypodactylia) Aicardi Syndrome AIDS Infection (see Fetal Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) Alaninuria (see Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Deficiency) Albers-Schonberg Disease (see Osteopetrosis, Malignant Recessive) Albinism, Ocular (includes Autosomal Recessive Type) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Brown Type (Type IV) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Tyrosinase Negative (Type IA) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Tyrosinase Positive (Type II) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Yellow Mutant (Type IB) Albinism-Black Locks-Deafness Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy (see Parathyroid Hormone Resistance) Alexander Disease Alopecia - Mental Retardation Alpers Disease Alpha 1,4 - Glucosidase Deficiency (see Glycogenosis, Type IIA) Alpha-L-Fucosidase Deficiency (see Fucosidosis) Alport Syndrome (see Nephritis-Deafness, Hereditary Type) Amaurosis (see Blindness) Amaurosis -

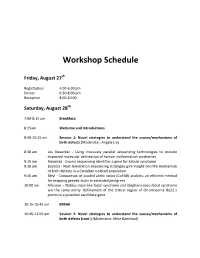

Workshop Schedule

Workshop Schedule Friday, August 27th Registration: 4:00‐6:30 pm Dinner 6:30‐8:00 pm Reception 8:00‐10:00 Saturday, August 28th 7:00‐8:15 am Breakfast: 8:15am Welcome and Introductions 8:30‐10:15 am Session 1: Novel strategies to understand the causes/mechanisms of birth defects (Moderator: Angela Lin) 8:30 am Les Biesecker ‐ Using massively parallel sequencing technologies to provide improved molecular delineation of human malformation syndromes 9:15 am Bamshad ‐ Exome sequencing identifies a gene for Kabuki syndrome 9:30 am Boycott ‐ Next‐Generation sequencing strategies give insight into the mechanism of birth defects in a Canadian isolated population 9:45 am Bleyl ‐ Comparison of pooled allelic ratios (CoPAR) analysis: an efficient method for mapping genetic traits in extended pedigrees 10:00 am Allanson – Nablus mask‐like facial syndrome and blepharo‐naso‐facial syndrome are the same entity. Refinement of the critical region of chromosome 8q22.1 points to a potential candidate gene 10:15‐10:45 am BREAK 10:45‐12:00 pm Session 2: Novel strategies to understand the causes/mechanisms of birth defects (cont.) (Moderator: Mike Bamshad) 10:45 am Krantz ‐ Applying novel genomic tools towards understanding an old chromosomal diagnosis: Using genome‐wide expression and SNP genotyping to identify the true cause of Pallister‐Killian syndrome 11:00 am Paciorkowski ‐ Bioinformatic analysis of published and novel copy number variants suggests candidate genes and networks for infantile spasms 11:15 am Bernier ‐ Identification of a novel Fibulin -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0210567 A1 Bevec (43) Pub

US 2010O2.10567A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0210567 A1 Bevec (43) Pub. Date: Aug. 19, 2010 (54) USE OF ATUFTSINASATHERAPEUTIC Publication Classification AGENT (51) Int. Cl. A638/07 (2006.01) (76) Inventor: Dorian Bevec, Germering (DE) C07K 5/103 (2006.01) A6IP35/00 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: A6IPL/I6 (2006.01) WINSTEAD PC A6IP3L/20 (2006.01) i. 2O1 US (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................... 514/18: 530/330 9 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 12/677,311 The present invention is directed to the use of the peptide compound Thr-Lys-Pro-Arg-OH as a therapeutic agent for (22) PCT Filed: Sep. 9, 2008 the prophylaxis and/or treatment of cancer, autoimmune dis eases, fibrotic diseases, inflammatory diseases, neurodegen (86). PCT No.: PCT/EP2008/007470 erative diseases, infectious diseases, lung diseases, heart and vascular diseases and metabolic diseases. Moreover the S371 (c)(1), present invention relates to pharmaceutical compositions (2), (4) Date: Mar. 10, 2010 preferably inform of a lyophilisate or liquid buffersolution or artificial mother milk formulation or mother milk substitute (30) Foreign Application Priority Data containing the peptide Thr-Lys-Pro-Arg-OH optionally together with at least one pharmaceutically acceptable car Sep. 11, 2007 (EP) .................................. O7017754.8 rier, cryoprotectant, lyoprotectant, excipient and/or diluent. US 2010/0210567 A1 Aug. 19, 2010 USE OF ATUFTSNASATHERAPEUTIC ment of Hepatitis BVirus infection, diseases caused by Hepa AGENT titis B Virus infection, acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, full minant liver failure, liver cirrhosis, cancer associated with Hepatitis B Virus infection. 0001. The present invention is directed to the use of the Cancer, Tumors, Proliferative Diseases, Malignancies and peptide compound Thr-Lys-Pro-Arg-OH (Tuftsin) as a thera their Metastases peutic agent for the prophylaxis and/or treatment of cancer, 0008. -

Craniosynostosis Precision Panel Overview Indications Clinical Utility

Craniosynostosis Precision Panel Overview Craniosynostosis is defined as the premature fusion of one or more cranial sutures, often resulting in abnormal head shape. It is a developmental craniofacial anomaly resulting from a primary defect of ossification (primary craniosynostosis) or, more commonly, from a failure of brain growth (secondary craniosynostosis). As well, craniosynostosis can be simple when only one suture fuses prematurely or complex/compound when there is a premature fusion of multiple sutures. Complex craniosynostosis are usually associated with other body deformities. The main morbidity risk is the elevated intracranial pressure and subsequent brain damage. When left untreated, craniosynostosis can cause serious complications such as developmental delay, facial abnormality, sensory, respiratory and neurological dysfunction, eye anomalies and psychosocial disturbances. In approximately 85% of the cases, this disease is isolated and nonsyndromic. Syndromic craniosynostosis usually present with multiorgan complications. The Igenomix Craniosynostosis Precision Panel can be used to make a directed and accurate diagnosis ultimately leading to a better management and prognosis of the disease. It provides a comprehensive analysis of the genes involved in this disease using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to fully understand the spectrum of relevant genes involved. Indications The Igenomix Craniosynostosis Precision Panel is indicated for those patients with a clinical diagnosis or suspicion with or without the following manifestations: ‐ Microcephaly ‐ Scaphocephaly (elongated head) ‐ Anterior plagiocephaly ‐ Brachycephaly ‐ Torticollis ‐ Frontal bossing Clinical Utility The clinical utility of this panel is: - The genetic and molecular confirmation for an accurate clinical diagnosis of a symptomatic patient. - Early initiation of treatment in the form surgical procedures to relieve fused sutures, midface advancement, limited phase of orthodontic treatment and combined 1 orthodontics/orthognathic surgery treatment. -

Vistara Non-Invasive Prenatal Screen

Vistara non-invasive prenatal screen Hypochondro- Causes a mild form of dwarsm; up to 80% Vistara identies probability for conditions that may have otherwise gone undetected until after birth plasia may cause seizures with secondary or into childhood. All conditions are inherited in an autosomal or X-linked dominant fashion, which means that FGFR3 developmental delay if the mutation is present, the child will be affected by the condition and experience related symptoms. Intellectual Causes intellectual disability and ~100% disability developmental delays SYNGAP1 Condition1 Clinical Cases Ultrasound ndings2,3 Clinical Detection Gene(s) synopsis2,3 caused by actionability rate for Jackson Weiss A type of craniosynostosis; more de novo None Third Non- gene1 syndrome also causes foot abnormalities severe mutations2,3 trimester specic FGFR2 forms Achondroplasia The most common form 80% Labor and delivery >96% FGFR3 of skeletal dysplasia; may management, monitor Juvenile A rare pediatric blood cancer; ve- unknown cause hydrocephalus, for spinal stenosis, early myelomonocytic year survival is approximately 50% delayed motor milestones, sleep studies to reduce leukemia (JMML) and spinal stenosis risk of SIDS PTPN11 Alagille Affects multiple organ systems 50% to 70% Symptom-based >86% LEOPARD Similar to Noonan syndrome, unknown syndrome and may cause growth problems, treatment syndrome 1,2 with notable brown skin spots JAG1 congenital heart defects, and (Noonan (lentigines); causes short stature, vertebral differences syndrome heart defects, bleeding