Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside This Issue from All Comers—Our Friends Included

May—June 2012 Volume 72, Number 3 SITREPT HE J OURNAL OF T HE R OYAL C ANADIAN M ILI TARY I NS T I T U T E Melbourne F Mackley archive/ ancestry.com —MELBOURNE F MACKLEY ARCHIVE/ANCESTRY.COM Defending Arctic sovereignty Inside this Issue from all comers—our friends included. The opening of the Can NATO Continue to be the Most Successful Alaska Highway on November Military Alliance in History? Yes it can! .................................................................................3 21, 1942, and a National Film Northern Sovereignty In World War II ...................................................................................5 Board photo—approved for The State of the World: A Framework ..................................................................................10 publication by US military Spent Nuclear Fuel:A National Security and authorities! Environmental Migraine Headache .......................................................................................12 Book Review: Dan Bjarnason, “Triumph at Kapyong: Canada’s Pivotal Battle in Korea” ..14 Turco-Syrian Border could become a flashpoint for NATO .................................................16 From the Editor’s Desk Can NATO Continue to be the Most Successful Military Alliance in History? Yes it can! he impact of the latest federal budget is beginning to be felt throughout the government and across the nation. by Sarwar Kashmeri The exact nature of reductions in the size and capabilities Royal Canadian Military Institute Tacross all departments and agencies has yet to be determined. Founded 1890 nce the world’s most formidable military alliance, assigned to ISAF have suffered numerous casualties because Clearly from a defence and security perspective short-term cuts Patron today’s NATO is a shadow of what it used to be. Its other contingents could not support them. This casualty count to address the deficit need to be examined in the long term. -

Étude De Huit Projets De Papineau Gérin-Lajoie Leblanc Architectes Pour

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL FIBRE ARCTIQUE: ÉTUDE DE HUIT PROJETS DE PAPINEAU GÉRIN-LAJOIE LEBLANC ARCHITECTES POUR LE NUNAVIK ET LE NUNAVUT (1968-1993) MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE À LA MAÎTRISE EN DESIGN DE L'ENVIRONNEMENT PAR FAYZA MAZOUZ OCTOBRE 2019 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 – Rév.07-2011). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l’article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l’auteur] concède à l’Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d’utilisation et de publication de la totalité ou d’une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l’auteur] autorise l’Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l’Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n’entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l’auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l’auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» b p .n ,. -,"'D L. .n 1 'U I' c- .,_""'V ::>p r L, n -:, .,_ n n -l b r :r: m p V C .n z V,. -

Northern Skytrails: Perspectives on the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic from the Pages of the Roundel, 1949-65 Richard Goette and P

Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security Northern Skytrails Perspectives on the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic from the Pages of The Roundel, 1949-65 Richard Goette and P. Whitney Lackenbauer Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security (DCASS) ISSN 2368-4569 Series Editors: P. Whitney Lackenbauer Adam Lajeunesse Managing Editor: Ryan Dean Northern Skytrails: Perspectives on the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic from the Pages of The Roundel, 1949-65 Richard Goette and P. Whitney Lackenbauer DCASS Number 10, 2017 Cover: The Roundel, vol. 1, no.1 (November 1948), front cover. Back cover: The Roundel, vol. 10, no.3 (April 1958), front cover. Centre for Military, Security and Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism Strategic Studies St. Jerome’s University University of Calgary 290 Westmount Road N. 2500 University Dr. N.W. Waterloo, ON N2L 3G3 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 519.884.8110 ext. 28233 Tel: 403.220.4030 www.sju.ca/cfpf www.cmss.ucalgary.ca Arctic Institute of North America University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW, ES-1040 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 403-220-7515 http://arctic.ucalgary.ca/ Copyright © the authors/editors, 2017 Permission policies are outlined on our website http://cmss.ucalgary.ca/research/arctic-document-series Northern Skytrails: Perspectives on the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic from the Pages of The Roundel, 1949-65 Richard Goette, Ph.D. and P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Ph.D. Table of Contents Preface: Pioneers of the North (by Wing Commander J. G. Showler) .................... vi Foreword (by Colonel Kelvin P. Truss) ................................................................... -

Iguess Many of Us Hanker After the Opportunity to Work Overseas

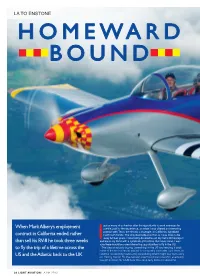

LA TO ENSTONE HOMEWARD BOUND When Mark Albery’s employment guess many of us hanker after the opportunity to work overseas for a while, just for the experience, so when I was offered an interesting contract with Tesla, the electric car people, in California, I grabbed contract in California ended, rather it with both hands. The only downside was that as I was likely to be away for four years, I reluctantly decided to sell my Van’s RV-8 project than sell his RV-8 he took three weeks and leave my RV-4 with a syndicate at Enstone. But never mind, I was Isure there would be some interesting opportunities to fl y in the US. to fl y the trip of a lifetime across the The idea of actually buying ‘something’ in the US and ferrying it back home at the end of the job started to form pretty soon after I got there, so US and the Atlantic back to the UK I started researching routes and considering what I might buy quite early on. Having had an RV, the decision wasn’t a diffi cult one and I eventually bought an RV-8, N713MB from Mike and Judy Ballard in Alabama. 5224 LIGHT AVIATIONAVIATION | JUNEMAY2011 2013 LA june - la to enstone.v3.EE.indd 50 24/05/2013 16:46 LA TO ENSTONE HOMEWARD BOUND I had a lot of fun fl ying in the US during my stay, met some great The critical leg for fuel planning purposes is the crossing of people and enjoyed being part of the Californian fl ying scene, but Greenland from west to east over the ice cap. -

Crystal to Iqaluit – 75 Years of Planning Engineering and Building

Leadership in Sustainable Infrastructure Leadership en Infrastructures Durables Vancouver, Canada May 31 – June 3, 2017/ Mai 31 – Juin 3, 2017 CRYSTAL TO IQALUIT – 75 YEARS OF PLANNING ENGINEERING AND BUILDING Johnson, Ken1,2 1 Planner, Engineer, and Historian, Cryofront, Edmonton, Alberta 2 [email protected] Abstract: The City of Iqaluit and its airfield is amongst a unique group of Canadian communities that originated entirely from a military presence, and reflects the origin of Louisburgg, and Kingston as strategic military hubs. From its origin as an airbase to serve the ferrying of aircraft from North America to Europe, Crystal II, then Frobisher Bay (1964), and finally Iqaluit (1987) has experienced 75 years of planning, engineering, and building. Iqaluit’s modern origins began in July 1941, during the Battle of the Atlantic, with the investigation of the Frobisher Bay region for a potential site as part of a series of military airfields on the great circle route to Europe. A non-military direction for the community, and the airfield came with John Diefenbaker’s 1958 grand vision for a domed community, but the grand vision disappeared when Diefenbaker lost power in 1962. Further community planning was completed in the years that followed, and these concepts were more realistic in the reflection of the climate, and terrain of the community. In 1963, the remaining military forces left, creating a Canadian government center, and a community in the eastern Arctic. Within the community itself, a central area became the community focus along with several surrounding residential areas. The community’s infrastructure included a piped water and sewer system, which pioneered the use of insulated buried pipe, and steel manholes. -

The Great Northern Dilemma: the Disconnection Between Canada's Security Policies and Canada's North

THE GREAT NORTHERN DILEMMA: THE DISCONNECTION BETWEEN CANADA'S SECURITY POLICIES AND CANADA'S NORTH LE DILEMME DU GRAND NORD : LE FOSSE ENTRE LES POLITIQUES DE SECURITE DU CANADA ET LES REALITES DU NORD CANADIEN A Thesis Submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies of the Royal Military College of Canada by Elizabeth Anne Sneyd Sub-Lieutenant (ret'd) In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in War Studies April 2008 © This thesis may be used within the Department of National Defence but copyright for open publication remains the property of the author. Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-42136-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-42136-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic

PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Edward P. Wood Edited and introduced by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Mulroney Institute of Government Arctic Operational Histories, no. 2 PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic © The author/editor 2017 Mulroney Institute St. Francis Xavier University 5005 Chapel Square Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada B2G 2W5 LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Per Ardua ad Arcticum: The Royal Canadian Air Force in the A rctic and Sub- Arctic / Edward P. Wood, author / P. Whitney Lackenbauer, editor (Arctic Operational Histories, no. 2) Issued in electronic and print formats ISBN (digital): 978-1-7750774-8-0 ISBN (paper): 978-1-7750774-7-3 1. Canada. Canadian Armed Forces—History--20th century. 2. Aeronautics-- Canada, Northern--History. 3. Air pilots--Canada, Northern. 4. Royal Canadian Air Force--History. 5. Canada, Northern--Strategic aspects. 6. Arctic regions--Strategic aspects. 7. Canada, Northern—History—20th century. I. Edward P. Wood, author II. Lackenbauer, P. Whitney Lackenbauer, editor III. Mulroney Institute of Government, issuing body IV. Per Adua ad Arcticum: The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic. V. Series: Arctic Operational Histories; no.2 Page design and typesetting by Ryan Dean and P. Whitney Lackenbauer Cover design by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Please consider the environment before printing this e-book PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Edward P. Wood Edited and Introduced by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Arctic Operational Histories, no.2 2017 The Arctic Operational Histories The Arctic Operational Histories seeks to provide context and background to Canada’s defence operations and responsibilities in the North by resuscitating important, but forgotten, Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) reports, histories, and defence material from previous generations of Arctic operations. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1942

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1942 updated 21/03/07 During the year the chief RCAF Medical Officer in England, W/C A.R. Tilley, moved from London to East Grinstead where his training in reconstructive surgery could be put to effective use (R. Donovan). See July 1944. January 1942 419 Sqn. begins to equip with Wellington Ic aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Air Marshal H. Edwards was posted from Ottawa, where as Air Member for Personnel he had overseen recruitment of instructors and other skilled people during the expansion of the BCATP, to London, England, to supervise the expansion of the RCAF overseas. There he finds that RCAF airmen sent overseas are not being tracked or properly supported by the RAF. At this time the location of some 6,000 RCAF airmen seconded to RAF units are unknown to the RCAF. He immediately takes steps to change this, and eventually had RCAF offices set up in Egypt and India to provide administrative support to RCAF airmen posted to these areas. He also begins pressing for the establishment of truly RCAF squadrons under Article 15 (a program sometimes referred to as "Canadianization"), despite great opposition from the RAF (E. Cable). He succeeded, but at the cost of his health, leading to his early retirement in 1944. Early in the year the Fa 223 helicopter was approved for production. In a program designed by E.A. Bott the results of psychological testing on 5,000 personnel selected for aircrew during 1942 were compared with the results of the actual training to determine which tests were the most useful. -

Building Capacity in Arctic Societies: Dynamics and Shifting Perspectives

International Ph.D. School for Studies of Arctic Societies (IPSSAS) Building Capacity in Arctic Societies: Dynamics and Shifting Perspectives Proceedings of the Second IPSSAS seminar Iqaluit, Nunavut, Canada May 26 to June 6, 2003 Edited by: François Trudel CIÉRA Faculté des sciences sociales Université Laval, Québec, Canada IPSSAS expresses its gratitude to the following institutions and departments for financially supporting or hosting the Second IPSSAS seminar in Iqaluit, Nunavut, Canada, in 2003: - Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade / Ministère des Affaires extérieures et du Commerce international du Canada - Nunavut Arctic College (Nunatta Campus) - Nunavut Research Institute - Université Laval – Vice-rectorat à la recherche and CIÉRA - Ilisimatusarfik/University of Greenland - Research Bureau of Greenland's Home Rule - The Commission for Scientific Research in Greenland (KVUG) - National Science Foundation through the Arctic Research Consortium of the United States - Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO), Paris, France - Ministère des Affaires étrangères de France - University of Copenhagen, Denmark The publication of these Proceedings has been possible through a contribution from the CANADIAN POLAR COMMISSION / COMMISSION CANADIENNE DES AFFAIRES POLAIRES Source of cover photo: IPSSAS Website International Ph.D. School for Studies of Arctic Societies (IPSSAS) Building Capacity in Arctic Societies: Dynamics and Shifting Perspectives Proceedings of the 2nd IPSSAS seminar, Iqaluit, -

The Historical and Legal Background of Canada's Arctic Claims

THE HISTORICAL AND LEGAL BACKGROUND OF CANADA’S ARCTIC CLAIMS ii © The estate of Gordon W. Smith, 2016 Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism St. Jerome’s University 290 Westmount Road N. Waterloo, ON, N2L 3G3 www.sju.ca/cfpf All rights reserved. This ebook may not be reproduced without prior written consent of the copyright holder. LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Smith, Gordon W., 1918-2000, author The Historical and Legal Background of Canada’s Arctic Claims ; foreword by P. Whitney Lackenbauer (Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism Monograph Series ; no.1) Issued in electronic format. ISBN: 978-0-9684896-2-8 (pdf) 1. Canada, Northern—International status—History. 2. Jurisdiction, Territorial— Canada, Northern—History. 3. Sovereignty—History. 4. Canada, Northern— History. 5. Canada—Foreign relations—1867-1918. 6. Canada—Foreign relations—1918-1945. I. Lackenbauer, P. Whitney, editor II. Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism, issuing body III. Title. IV. Series: Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism Monograph Series ; no.1 Page designer and typesetting by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Cover design by Daniel Heidt Distributed by the Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism Please consider the environment before printing this e-book THE HISTORICAL AND LEGAL BACKGROUND OF CANADA’S ARCTIC CLAIMS Gordon W. Smith Foreword by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism Monograph Series 2016 iv Dr. Gordon W. Smith (1918-2000) Foreword FOREWORD Dr. Gordon W. Smith (1918-2000) dedicated most of his working life to the study of Arctic sovereignty issues. Born in Alberta in 1918, Gordon excelled in school and became “enthralled” with the history of Arctic exploration. -

Crystal Two: the Origin of Iqaluit ROBERT V

ARCTIC VOL. 56, NO. 1 (MARCH 2003) P. 63–75 Crystal Two: The Origin of Iqaluit ROBERT V. ENO1 (Received 8 November 2001; accepted in revised form 25 June 2002) ABSTRACT. Iqaluit is unique among Canadian Arctic communities in that it originated not from a commercial venture, such as mining or the fur trade, or as a government administrative centre, but as a Second World War military airfield. This airfield, though never fully used for its intended purpose as a refueling base for short-range military aircraft en route from America to Great Britain, is the cornerstone of the city of Iqaluit. It opened the region to development during the postwar years. As a result, Iqaluit became a key transportation and communication hub for the eastern Arctic and, ultimately, the capital city of the new territory of Nunavut. This survey of Iqaluit’s wartime origins and subsequent development focuses on four topics. The first is the pre-war and wartime effort to establish an air route from North America to Europe via the Arctic; the second, the world events that precipitated construction of a series of northern airfields, including Crystal Two, that would form the links in the Crimson Air Route. The third is the importance of the Crystal Two airfield for the postwar development of Iqaluit, and the final focus is on the resourceful individuals who pulled it all together, overcoming a myriad of apparently insurmountable obstacles to complete their mission. Key words: Crimson Route, Crowell, Crystal Two, Forbes, Frobisher Bay, Hubbard, Iqaluit, Roosevelt, Second World War, United States Army Air Forces, U-boat RÉSUMÉ. -

Creation of Autonomous Government in Nunavik

Creation of Autonomous Government in Nunavik Jean-François Arteau* Nunavik (large land), is the territory located north of the 55th parallel in the Province of Quebec, Canada. Its land mass is 507,000 sq km., the size of France. Total population is 11,000 of which 90% are Inuit. They live in 14 coastal communities; more than 50% of the Inuit population is less than 20 years old. Access to the territory of Nunavik is only possible by plane and sealift. Major employment lies with the public and para-public sectors, tour- ism, services, mining, transportation, Inuit art etc. The cost of living is 70% higher compared to Quebec City, the capital of the Province of Quebec. Inuit pay taxes like any other Canadian.1 Starting in the 16th century, and over the next three centuries, naviga- tors from several European countries (for example, from England, France, Portugal) sought a Northwest Passage to Asia. About the same time, King Charles II of England grants the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) a trading monopoly over much of what is now known as the Canadian North. But, an event that took place 60 years ago, that will have major effects on the Canadian North and the Inuit, was the outbreak of World War II, which lead to the establishment of military bases in the North. Prior to WWII, the only non-Inuit visitors to that region were the HBC, missionaries of different denominations (Anglican, Roman Catholic, Moravians), explorers, mining prospectors, Scottish and American whalers. WWII catapulted the North, the Arctic and its inhabitants to the world scene, not only in Canada but also in Alaska and Greenland.