Crystal to Iqaluit – 75 Years of Planning Engineering and Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside This Issue from All Comers—Our Friends Included

May—June 2012 Volume 72, Number 3 SITREPT HE J OURNAL OF T HE R OYAL C ANADIAN M ILI TARY I NS T I T U T E Melbourne F Mackley archive/ ancestry.com —MELBOURNE F MACKLEY ARCHIVE/ANCESTRY.COM Defending Arctic sovereignty Inside this Issue from all comers—our friends included. The opening of the Can NATO Continue to be the Most Successful Alaska Highway on November Military Alliance in History? Yes it can! .................................................................................3 21, 1942, and a National Film Northern Sovereignty In World War II ...................................................................................5 Board photo—approved for The State of the World: A Framework ..................................................................................10 publication by US military Spent Nuclear Fuel:A National Security and authorities! Environmental Migraine Headache .......................................................................................12 Book Review: Dan Bjarnason, “Triumph at Kapyong: Canada’s Pivotal Battle in Korea” ..14 Turco-Syrian Border could become a flashpoint for NATO .................................................16 From the Editor’s Desk Can NATO Continue to be the Most Successful Military Alliance in History? Yes it can! he impact of the latest federal budget is beginning to be felt throughout the government and across the nation. by Sarwar Kashmeri The exact nature of reductions in the size and capabilities Royal Canadian Military Institute Tacross all departments and agencies has yet to be determined. Founded 1890 nce the world’s most formidable military alliance, assigned to ISAF have suffered numerous casualties because Clearly from a defence and security perspective short-term cuts Patron today’s NATO is a shadow of what it used to be. Its other contingents could not support them. This casualty count to address the deficit need to be examined in the long term. -

Étude De Huit Projets De Papineau Gérin-Lajoie Leblanc Architectes Pour

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL FIBRE ARCTIQUE: ÉTUDE DE HUIT PROJETS DE PAPINEAU GÉRIN-LAJOIE LEBLANC ARCHITECTES POUR LE NUNAVIK ET LE NUNAVUT (1968-1993) MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE À LA MAÎTRISE EN DESIGN DE L'ENVIRONNEMENT PAR FAYZA MAZOUZ OCTOBRE 2019 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 – Rév.07-2011). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l’article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l’auteur] concède à l’Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d’utilisation et de publication de la totalité ou d’une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l’auteur] autorise l’Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l’Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n’entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l’auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l’auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» b p .n ,. -,"'D L. .n 1 'U I' c- .,_""'V ::>p r L, n -:, .,_ n n -l b r :r: m p V C .n z V,. -

CNGO NU Summary-Of-Activities

SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES 2015 © 2015 by Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office. All rights reserved. Electronic edition published 2015. This publication is also available, free of charge, as colour digital files in Adobe Acrobat® PDF format from the Canada- Nunavut Geoscience Office website: www.cngo.ca/ Every reasonable effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this report, but Natural Resources Canada does not assume any liability for errors that may occur. Source references are included in the report and users should verify critical information. When using information from this publication in other publications or presentations, due acknowledgment should be given to Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office. The recommended reference is included on the title page of each paper. The com- plete volume should be referenced as follows: Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office (2015): Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office Summary of Activities 2015; Canada- Nunavut Geoscience Office, 208 p. ISSN 2291-1235 Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office Summary of Activities (Print) ISSN 2291-1243 Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office Summary of Activities (Online) Front cover photo: Sean Noble overlooking a glacially eroded valley, standing among middle Paleoproterozoic age psam- mitic metasedimentary rocks, nine kilometres west of Chidliak Bay, southern Baffin Island. Photo by Dustin Liikane, Carleton University. Back cover photo: Iqaluit International Airport under rehabilitation and expansion; the Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Of- fice, Geological Survey of Canada (Natural Resources Canada), Centre d’études nordiques (Université Laval) and Trans- port Canada contributed to a better understanding of permafrost conditions to support the planned repairs and adapt the in- frastructure to new climatic conditions. Photo by Tommy Tremblay, Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office. -

Northern Skytrails: Perspectives on the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic from the Pages of the Roundel, 1949-65 Richard Goette and P

Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security Northern Skytrails Perspectives on the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic from the Pages of The Roundel, 1949-65 Richard Goette and P. Whitney Lackenbauer Documents on Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security (DCASS) ISSN 2368-4569 Series Editors: P. Whitney Lackenbauer Adam Lajeunesse Managing Editor: Ryan Dean Northern Skytrails: Perspectives on the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic from the Pages of The Roundel, 1949-65 Richard Goette and P. Whitney Lackenbauer DCASS Number 10, 2017 Cover: The Roundel, vol. 1, no.1 (November 1948), front cover. Back cover: The Roundel, vol. 10, no.3 (April 1958), front cover. Centre for Military, Security and Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism Strategic Studies St. Jerome’s University University of Calgary 290 Westmount Road N. 2500 University Dr. N.W. Waterloo, ON N2L 3G3 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 519.884.8110 ext. 28233 Tel: 403.220.4030 www.sju.ca/cfpf www.cmss.ucalgary.ca Arctic Institute of North America University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW, ES-1040 Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Tel: 403-220-7515 http://arctic.ucalgary.ca/ Copyright © the authors/editors, 2017 Permission policies are outlined on our website http://cmss.ucalgary.ca/research/arctic-document-series Northern Skytrails: Perspectives on the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic from the Pages of The Roundel, 1949-65 Richard Goette, Ph.D. and P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Ph.D. Table of Contents Preface: Pioneers of the North (by Wing Commander J. G. Showler) .................... vi Foreword (by Colonel Kelvin P. Truss) ................................................................... -

Iguess Many of Us Hanker After the Opportunity to Work Overseas

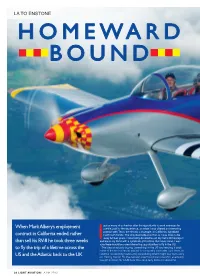

LA TO ENSTONE HOMEWARD BOUND When Mark Albery’s employment guess many of us hanker after the opportunity to work overseas for a while, just for the experience, so when I was offered an interesting contract with Tesla, the electric car people, in California, I grabbed contract in California ended, rather it with both hands. The only downside was that as I was likely to be away for four years, I reluctantly decided to sell my Van’s RV-8 project than sell his RV-8 he took three weeks and leave my RV-4 with a syndicate at Enstone. But never mind, I was Isure there would be some interesting opportunities to fl y in the US. to fl y the trip of a lifetime across the The idea of actually buying ‘something’ in the US and ferrying it back home at the end of the job started to form pretty soon after I got there, so US and the Atlantic back to the UK I started researching routes and considering what I might buy quite early on. Having had an RV, the decision wasn’t a diffi cult one and I eventually bought an RV-8, N713MB from Mike and Judy Ballard in Alabama. 5224 LIGHT AVIATIONAVIATION | JUNEMAY2011 2013 LA june - la to enstone.v3.EE.indd 50 24/05/2013 16:46 LA TO ENSTONE HOMEWARD BOUND I had a lot of fun fl ying in the US during my stay, met some great The critical leg for fuel planning purposes is the crossing of people and enjoyed being part of the Californian fl ying scene, but Greenland from west to east over the ice cap. -

Polar Bear Hunting: Three Areas \Vere Most Important for Hunting Was Less Mtensive South of Shaftesbury Inlet, Where Polar Bear

1Ire8, whenever seen, most often when people • SlImmary: In compan on with othcr Kcc\\attn settlements. ibou or trappmg. the people of Chesterfield use a rclati\"cl) small arca of land. ÏlItt11iDl Hunting. 80th ringed and bearded seals Chesterfield is a small c1osc-knit seulement. and evcryone year rooud. In sommer people hunt along shares the land and game of the area. There is usually JnIet toParther Hope Point including Barbour suffieient supply of game nearby without their having to e coast from Whale Cove to Karmarvik Harbour, travel very far. Many people are also wage carners and are omiles mland. For mueh of the year people hunt Iimited to day and weekend hunting trips, exeept for holiday' 'h . d 1 oe èdge, which is usually three or four miles out ln t e spnng an summer. ement; however, the distance varies along The area most important to the people of Chesterfield is !'the pnncipal seal hunting season is spring, w en the mouth of the inlet. north along the coast from Cape the ice. At this time, too, young seals are hunted Silumiut to Daly Bay: and ülland to nearby caribou hunting lairs. The area from Baker Foreland to Bern and fishmg areas. ThiS rcglOn 15 nch ln gamc. and il COI1 and along Chesterfield Inlet to Big Island is weil stitutes the traditional hunting ground for 1110st of the :Cape Silumiut area is extremely popular for week Chesterfield people. Il does not overlap with land cOJnmonly trips, and people often hunt atthe floe edge near used by any other seUlement, although people from Rankin t. -

Canada Topographical

University of Waikato Library: Map Collection Canada: topographical maps 1: 250,000 The Map Collection of the University of Waikato Library contains a comprehensive collection of maps from around the world with detailed coverage of New Zealand and the Pacific : Editions are first unless stated. These maps are held in storage on Level 1 Please ask a librarian if you would like to use one: Coverage of Canadian Provinces Province Covered by sectors On pages Alberta 72-74 and 82-84 pp. 14, 16 British Columbia 82-83, 92-94, 102-104 and 114 pp. 16-20 Manitoba 52-54 and 62-64 pp. 10, 12 New Brunswick 21 and 22 p. 3 Newfoundland and Labrador 01-02, 11, 13-14 and 23-25) pp. 1-4 Northwest Territories 65-66, 75-79, 85-89, 95-99 and 105-107) pp. 12-21 Nova Scotia 11 and 20-210) pp. 2-3 Nunavut 15-16, 25-27, 29, 35-39, 45-49, 55-59, 65-69, 76-79, pp. 3-7, 9-13, 86-87, 120, 340 and 560 15, 21 Ontario 30-32, 40-44 and 52-54 pp. 5, 6, 8-10 Prince Edward Island 11 and 21 p. 2 Quebec 11-14, 21-25 and 31-35 pp. 2-7 Saskatchewan 62-63 and 72-74 pp. 12, 14 Yukon 95,105-106 and 115-117 pp. 18, 20-21 The sector numbers begin in the southeast of Canada: They proceed west and north. 001 Newfoundland 001K Trepassey 3rd ed. 1989 001L St: Lawrence 4th ed. 1989 001M Belleoram 3rd ed. -

The Great Northern Dilemma: the Disconnection Between Canada's Security Policies and Canada's North

THE GREAT NORTHERN DILEMMA: THE DISCONNECTION BETWEEN CANADA'S SECURITY POLICIES AND CANADA'S NORTH LE DILEMME DU GRAND NORD : LE FOSSE ENTRE LES POLITIQUES DE SECURITE DU CANADA ET LES REALITES DU NORD CANADIEN A Thesis Submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies of the Royal Military College of Canada by Elizabeth Anne Sneyd Sub-Lieutenant (ret'd) In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in War Studies April 2008 © This thesis may be used within the Department of National Defence but copyright for open publication remains the property of the author. Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-42136-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-42136-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

Royal Canadian Mounted Police

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. DOMINION OF CANADA REPORT OF THE ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE FOR THE YEAR. ENDED SEPTEMBER 30, 1930 OTTAWA F. A. ACLAND PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1931 l'ricc, 2,3 cents. DOMINION OF CANADA REPORT OF THE ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE FOR THE YEAR ENDED SEPTEMBER 30, 1930 Li 'OTTAWA F. -

Proceedings from the First International Conference on Urbanisation in the Arctic Conference 28-30 August 2012 Ilimmarfik, Nuuk, Greenland

Proceedings from the First International Conference on Urbanisation in the Arctic Conference 28-30 August 2012 Ilimmarfik, Nuuk, Greenland Klaus Georg Hansen, Rasmus Ole Rasmussen and Ryan Weber (editors) NORDREGIO WORKING PAPER 2013:6 Proceedings from the First International Conference on Urbanisation in the Arctic Conference 28-30 August 2012 Ilimmarfik, Nuuk, Greenland Proceedings from the First International Conference on Urbanisation in the Arctic Conference 28-30 August 2012 Ilimmarfik, Nuuk, Greenland Klaus Georg Hansen, Rasmus Ole Rasmussen and Ryan Weber (editors) Proceedings from the First International Conference on Urbanisation in the Arctic Conference 28-30 August 2012, Ilimmarfik, Nuuk, Greenland Nordregio Working Paper 2013:6 ISBN 978-91-87295-07-2 ISSN 1403-2511 © Nordregio 2013 Nordregio P.O. Box 1658 SE-111 86 Stockholm, Sweden [email protected] www.nordregio.se www.norden.org Editors: Klaus Georg Hansen, Rasmus Ole Rasmussen and Ryan Weber Front page photos: Klaus Georg Hansen Nordic co-operation Nordic co-operation is one of the world’s most extensive forms of regional collaboration, involving Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. Nordic co-operation has firm traditions in politics, the economy, and culture. It plays an important role in European and inter- national collaboration, and aims at creating a strong Nordic community in a strong Europe. Nordic co-operation seeks to safeguard Nordic and regional interests and principles in the global community. Common Nordic values help the region solidify its position as one of the world’s most innovative and competitive. The Nordic Council is a forum for co-operation between the Nordic parliaments and governments. -

I[NUVIK and CWRCHILL, 19554970 MA. Rogram

THE HISTORY OF TEE FEDERAb RESIDE- SCHOOLS FOR TEiE INUIT LOCATED IN CHESTERFIELD INLET, YELLOWKNIFE, I[NUVIK AND CWRCHILL, 19554970 A Thesis submitted to the Cornmittee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulnlment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Facuity of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada @ Copyright by David Paul King, 1998 Canadiau Heritage and Developmnt Studies MA. Rogram National Cibrary Bibliothèque nationale du Canada uisitions and Acquisitions et "9-Bib iographii Sewices services bibliographiques 395 Weiikigton Street 395, rue Wellington OItawaON KlAON4 OltawaON KIAW Canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libraxy of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriaute or seîi reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thése sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thése ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celleci ne doivent être imprimes reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE HISTORY OF THE FEDERAL RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS FOR THE INUIT LOCATED IN CHESTERFIELD INLET, YELLOWKNIFE, INUVIK AND CHURCHIL&, 1955-1970. DAVID KING It îs the purpose of this thesis to record the history of the federal goverment's record regarding the northern school system and the residential schools in relation to the Inuit from the inauguration of the school system in 1955 to 1970, when responsibility for education in the north was delegated to the new N. -

PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM the Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic

PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Edward P. Wood Edited and introduced by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Mulroney Institute of Government Arctic Operational Histories, no. 2 PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic © The author/editor 2017 Mulroney Institute St. Francis Xavier University 5005 Chapel Square Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada B2G 2W5 LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Per Ardua ad Arcticum: The Royal Canadian Air Force in the A rctic and Sub- Arctic / Edward P. Wood, author / P. Whitney Lackenbauer, editor (Arctic Operational Histories, no. 2) Issued in electronic and print formats ISBN (digital): 978-1-7750774-8-0 ISBN (paper): 978-1-7750774-7-3 1. Canada. Canadian Armed Forces—History--20th century. 2. Aeronautics-- Canada, Northern--History. 3. Air pilots--Canada, Northern. 4. Royal Canadian Air Force--History. 5. Canada, Northern--Strategic aspects. 6. Arctic regions--Strategic aspects. 7. Canada, Northern—History—20th century. I. Edward P. Wood, author II. Lackenbauer, P. Whitney Lackenbauer, editor III. Mulroney Institute of Government, issuing body IV. Per Adua ad Arcticum: The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic. V. Series: Arctic Operational Histories; no.2 Page design and typesetting by Ryan Dean and P. Whitney Lackenbauer Cover design by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Please consider the environment before printing this e-book PER ARDUA AD ARCTICUM The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic Edward P. Wood Edited and Introduced by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Arctic Operational Histories, no.2 2017 The Arctic Operational Histories The Arctic Operational Histories seeks to provide context and background to Canada’s defence operations and responsibilities in the North by resuscitating important, but forgotten, Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) reports, histories, and defence material from previous generations of Arctic operations.