BMC 36 - VIVALDI-BACH: Concerto Transcriptions for Harpsichord

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

Natura Artificiale Di Vivaldi

TORINO Martedì 5 settembre Conservatorio Giuseppe Verdi ore 17 LA NATURA ARTIFICIALE DI VIVALDI natura www.mitosettembremusica.it LA NATURA ARTIFICIALE DI VIVALDI Nei primissimi anni del Settecento, intrisi di razionalismo, si parla in continuazione di «Natura» come modello, e la naturalezza è il fine d’ogni arte. Quello che crea Vivaldi, molto baroccamente, è una finta natura: l’estremo artificio formale mascherato da gesto normale, spontaneo. E tutti ci crederanno. Il concerto è preceduto da una breve introduzione di Stefano Catucci Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Concerto in la minore per due violini e archi da L’Estro Armonico op. 3 n. 8 RV 522a Allegro – [Adagio] – [Allegro] Sonata in sol maggiore per violino, violoncello e basso continuo RV 820 Allegro – Adagio – Allegro Concerto in re minore per violino, archi e basso continuo RV 813 (ms. Wien, E.M.) Allegro – [Adagio] – Allegro – Adagio – Andante – Largo – Allegro Concerto in sol maggiore per flauto traversiere, archi e basso continuo RV 438 Allegro – Larghetto – Allegro Sonata in re minore per due violini e basso continuo “La follia” op. 1 n. 12 RV 63 Tema (Adagio). Variazioni Giovanni Stefano Carbonelli (1694-1772) Sonata op. 1 n. 2 in re minore Adagio – Allegro Allegro Andante Aria Antonio Vivaldi Concerto in mi minore per violino, archi e basso continuo da La Stravaganza op. 4 n. 2 RV 279 Allegro – Largo – Allegro Modo Antiquo Federico Guglielmo violino principale Raffaele Tiseo, Paolo Cantamessa, Stefano Bruni violini Pasquale Lepore viola Bettina Hoffmann violoncello Federico Bagnasco contrabbasso Andrea Coen clavicembalo Federico Maria Sardelli direttore e flauto traversiere /1 Vivaldi natura renovatur. -

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 Pm

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 pm Photo:Photo: Benoit © Paul Lemay Kolnik 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PETER MARTINS ARTISTIC ADMINISTRATOR JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH THE DANCERS PRINCIPALS ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING CHASE FINLAY ABI STAFFORD SOLOIST UNITY PHELAN CORPS DE BALLET MARIKA ANDERSON JACQUELINE BOLOGNA HARRISON COLL CHRISTOPHER GRANT SPARTAK HOXHA RACHEL HUTSELL BAILY JONES ALEC KNIGHT OLIVIA MacKINNON MIRIAM MILLER ANDREW SCORDATO PETER WALKER THE MUSICIANS ARTURO DELMONI, VIOLIN ELAINE CHELTON, PIANO ALAN MOVERMAN, PIANO BALLET MASTERS JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH CRAIG HALL LISA JACKSON REBECCA KROHN CHRISTINE REDPATH KATHLEEN TRACEY TOURING STAFF FOR NEW YORK CITY BALLET MOVES COMPANY MANAGER STAGE MANAGER GREGORY RUSSELL NICOLE MITCHELL LIGHTING DESIGNER WARDROBE MISTRESS PENNY JACOBUS MARLENE OLSON HAMM WARDROBE MASTER MASTER CARPENTER JOHN RADWICK NORMAN KIRTLAND III 3 Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop Photo © Paul Kolnik for all of your instrument, EVENT SPONSORS accessory, and service needs! RICHARD AND MARY JO STANLEY ELLIE AND PETER DENSEN ALLYN L. MARK IOWA HOUSE HOTEL SEASON SPONSOR WEST MUSIC westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Photo: Miriam Alarcón Avila Season Sponsor! Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop for all of your instrument, accessory, and service needs! westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Season Sponsor! THE PROGRAM IN THE NIGHT Music by FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN Choreography by JEROME ROBBINS Costumes by ANTHONY DOWELL Lighting by JENNIFER TIPTON OLIVIA MacKINNON UNITY PHELAN ABI STAFFORD AND AND AND ALEC KNIGHT CHASE FINLAY ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING Piano: ELAINE CHELTON This production was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. -

Antonio Lucio VIVALDI

AN IMPORTANT NOTE FROM Johnstone-Music ABOUT THE MAIN ARTICLE STARTING ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE: We are very pleased for you to have a copy of this article, which you may read, print or save on your computer. You are free to make any number of additional photocopies, for johnstone-music seeks no direct financial gain whatsoever from these articles; however, the name of THE AUTHOR must be clearly attributed if any document is re-produced. If you feel like sending any (hopefully favourable) comment about this, or indeed about the Johnstone-Music web in general, simply vis it the ‘Contact’ section of the site and leave a message with the details - we will be delighted to hear from you ! Una reseña breve sobre VIVALDI publicado por Músicos y Partituras Antonio Lucio VIVALDI Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Venecia, 4 de marzo de 1678 - Viena, 28 de julio de 1741). Compositor del alto barroco, apodado il prete rosso ("el cura rojo" por ser sacerdote y pelirrojo). Compuso unas 770 obras, entre las cuales se cuentan 477 concerti y 46 óperas; especialmente conocido a nivel popular por ser el autor de Las cuatro estaciones. johnstone-music Biografia Vivaldi un gran compositor y violinista, su padre fue el violinista Giovanni Batista Vivaldi apodado Rossi (el Pelirrojo), fue miembro fundador del Sovvegno de’musicisti di Santa Cecilia, organización profesional de músicos venecianos, así mismo fue violinista en la orquesta de la basílica de San Marcos y en la del teatro de S. Giovanni Grisostomo., fue el primer maestro de vivaldi, otro de los cuales fue, probablemente, Giovanni Legrenzi. -

Antonio Vivaldi from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Antonio Vivaldi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo ˈluːtʃo viˈvaldi]; 4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian Baroque composer, virtuoso violinist, teacher and cleric. Born in Venice, he is recognized as one of the greatest Baroque composers, and his influence during his lifetime was widespread across Europe. He is known mainly for composing many instrumental concertos, for the violin and a variety of other instruments, as well as sacred choral works and more than forty operas. His best-known work is a series of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons. Many of his compositions were written for the female music ensemble of the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for abandoned children where Vivaldi (who had been ordained as a Catholic priest) was employed from 1703 to 1715 and from 1723 to 1740. Vivaldi also had some success with expensive stagings of his operas in Venice, Mantua and Vienna. After meeting the Emperor Charles VI, Vivaldi moved to Vienna, hoping for preferment. However, the Emperor died soon after Vivaldi's arrival, and Vivaldi himself died less than a year later in poverty. Life Childhood Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was born in 1678 in Venice, then the capital of the Republic of Venice. He was baptized immediately after his birth at his home by the midwife, which led to a belief that his life was somehow in danger. Though not known for certain, the child's immediate baptism was most likely due either to his poor health or to an earthquake that shook the city that day. -

Concerto.MUS

ANTONIO VIVALDI (Venezia 1678 - Wien 1741) CONCERTO RV 93 (F. XII n. 15) con 2 Violini Leuto, e Basso Del Vivaldi P.S.E. Il Conte Wrttby Urtext edition by Fabio Rizza based on the original manuscript housed in the Biblioteca Nazionale, Turin, Italy, "Renzo Giordani Collection", vol. 35, fol. 297 - 302 [email protected] PREFACE 3 CONCERTO RV 93 4 1. [Allegro giusto] 4 2. Largo 8 3. Allegro 10 BIBLIOGRAPHY/BIBLIOGRAFIA 13 DISCOGRAPHY/DISCOGRAFIA 14 PREFACE Probably this Concerto con 2 Violini Leuto, e Basso has been written in the early 1730s, when Vivaldi was in Prague, and it's dedicated to a Bohemian Count, Johann Joseph von Wrtby (Jan Josef Vrtba, according to the Czech form). The present edition is a faithful copy of the autograph housed in the Biblioteca Nazionale, Turin (Italy), "Renzo Giordani Collection", vol. 35, fol. 297 - 302. I've corrected only an obvious mistake (a C-sharp instead of a B) in measure 9 of the second movement. The music has been engraved in Finale 98. PREFAZIONE È probabile che questo Concerto con 2 Violini Leuto, e Basso sia stato scritto intorno al 1730, mentre Vivaldi si trovava a Praga, ed è dedicato al conte boemo Johann Joseph von Wrtby (o Jan Josef Vrtba, secondo la grafia ceca). Questa edizione è una copia fedele del manoscritto autografo conservato presso la Biblioteca Nazionale di Torino, fondo "Renzo Giordani", vol. 35, fol. 297 - 302. Mi sono limitato a correggere un palese errore (un do diesis al posto di un si) a misura 9 del secondo movimento. -

Spread the Word • Promote the Show • Support Public

PROGRAM NO. 1931 8/5/2019 Prelude. MAX REGER: Toccata in d, Op. 129, Clement’s Church, Prague, Czech Republic) Vars It’s Greek to Me . these works on classical no. 1 –Amanda Mole (1984 Marcussen/Musashino 0006 Greek themes remind us that it was a Greek Civic Cultural Hall, Tokyo, Japan) Naxos 8.573912 VIVALDI (trans. Bach): Concerto in D/C, RV 208 engineer, Ctesibius, who invented the pipe FLORENCE PRICE: Fantasy & Air, fr Suite No. 1 (BWV 594) –Claudio Brizi (1756 Migendt/Zur organ more than 2300 years ago! –Robert Parkins (1932 Aeolian/Duke University frohen Botschaft Church, Berlin-Karlshorst, Chapel, Durham, NC) Loft 1147 Germany) Quadrivium 022 J-B LULLY: March, fr Alceste –Michel Chapuis (1710 DAVE BRUBECK: Two-Part Contention –Jan VIVALDI: Concerto in F for Violin, Organ and Clicquot/Versailles Palace Chapel, France) Palace Kraybill (2015 Quimby/4th Presbyterian Church, Strings, RV 542 –Il Rossignolo Ensemble/Fabio Versailles 004 Chicago, IL) Quimby 2019 Cafaro, violin; Ottaviano Tenerani (1992 Chichi JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU (trans. Rechsteiner): PAUL FISHER: The White Tiger –Gabrielle Bullock, chamber organ) Tactus 672239 Ballet excerpts (Sarabande, fr Zoroastre; Air reader; Richard Cook (2008 Tickel/Worcester VIVALDI (trans. Todorovski): Concerto in c, Op. 4, tendre, fr Dardanus; Tambourin, fr Les Fete Cathedral, England) Regent 520 no. 10, fr La Stravaganza –Catherine Todorovski d’Hébé) –Henri-Charles Caget, percussion; Yves FREDRIK SIXTEN: Nordic Variations –James D. (1982 Grenzing/St. Cyprien, Périgord, France) Rechsteiner (1741 Moucherel-1754 Lepine/Church Hicks (1992 Klais/Hallgrimskirkja, Rejkjavik, Syrius 252474 of the Nativity of the Virgin, Cintegabelle, France) Iceland) Pro Organo 7287 Alpha 650 T. -

Vivaldi Antonio

VIVALDI ANTONIO Violinista e compositore italiano (Venezia 4 III 1678 - Vienna 26 o 28 VII 1741) 1 Detto il "prete rosso", dal colore dei suoi capelli, secondo la testimonianza di Goldoni, nacque da una famiglia veneziana benestante, d'origine genovese, come denuncia il nome. Il padre, Giovanni Battista, era violinista "professionista" nel senso che aveva la parola in Venezia nel XVI sec., ed esercitava la professione suonando il violino, forse, componendo nella Ducale cappella di San Marco. La madre si chiamava Camilla Calicchio. Il bambino, al quale furono imposti i nomi di Antonio Lucio, fu battezzato in San Giovanni in Bràgora il 6 maggio. Cagionevole di salute fin dalla nascita, soffrì sempre, come egli stesso farà sapere in una lettera del 1737, di una malattia congenita alle vie respiratorie: "ristrettezza del petto" egli la chiamava, lasciandoci in dubbio tra l'asma e la tisi. Ebbe tre fratelli, tutti nati dopo di lui, di nome Iseppo, Francesco, Bonaventura, i quali condussero una vita precaria e non sempre onorata. Il padre volle per il suo primogenito Antonio la carriera ecclesiastica, sollecitato in ciò dalla madre che pensava, così facendo, di proteggere la salute del fanciullo. Perciò percorse regolarmente e superò tutti i gradi per giungere all'ordinazione: fu tonsurato il 18 IX 1693 e ricevette i voti della sacra ordinazione, al termine del diacononato, il 23 III 1703: in questo stesso anno ebbe anche il notevole privilegio di entrare presso il Pio Ospitale della Pietà come insegnante di violino. La Pietà era il più in vista ed il meglio frequentato dei quattro ospizi di carità (La Pietà, Gl'Incurabili, L'Ospedaletto, I Mendicanti) che, in Venezia, possedessero anche attigui istituti musicali perfettamente attrezzati e cospiquamente finanziati dallo Stato e da privati. -

Antonio Vivaldi

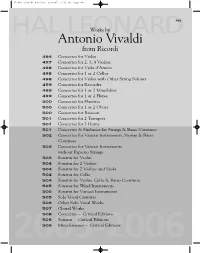

97144A Vivaldi 493-509 8/29/05 2:50 PM Page 493 493 Works by Antonio Vivaldi from Ricordi 494 Concertos for Violin 497 Concertos for 2, 3, 4 Violins 498 Concertos for Viola d’Amore 498 Concertos for 1 or 2 Cellos 498 Concertos for Violin with Other String Soloists 499 Concertos for Recorder 499 Concertos for 1 or 2 Mandolins 499 Concertos for 1 or 2 Flutes 500 Concertos for Flautino 500 Concertos for 1 or 2 Oboes 500 Concertos for Bassoon 501 Concertos for 2 Trumpets 501 Concertos for 2 Horns 501 Concertos & Sinfonias for Strings & Basso Continuo 502 Concertos for Various Instruments, Strings & Basso Continuo 503 Concertos for Various Instruments without Ripieno Strings 503 Sonatas for Violin 504 Sonatas for 2 Violins 504 Sonatas for 2 Violins and Viola 504 Sonatas for Cello 504 Sonatas for Violin, Cello & Basso Continuo 505 Sonatas for Wind Instruments 505 Sonatas for Various Instruments 505 Solo Vocal Cantatas 506 Other Solo Vocal Works 507 Choral Works 508 Concertos – Critical Editions 508 Sonatas – Critical Editions 509 Miscellaneous – Critical Editions 97144A Vivaldi 493-509 8/29/05 2:50 PM Page 494 494 WORKS BY ANTONIO VIVALDI FROM RICORDI CRITICAL EDITION ______50037670 C Major RV186, T.13, F.I No. 3 (Maderna) • Sets (3-3-2-2-1) available for sale. (Other parts may be available on rental.) Ricordi RPR249 .........................................................$15.00 The reference T. (TOMO) refers to the order in which each volume appeared in ______50041590 C Major RV581, T.55, F.I No. 13 (with double orchestra) the Ricordi Edition. -

Season 2016/17

SEASON 2016/17 CORPORATE PARTNERS THANK YOU MASS MEDIA FOR MAKING IT POSSIBLE ABC Agència EFE Barcelona TV Expansión SPECIAL PROJECT SUPPORTERS EL PETIT LICEU CORPORATE SUPPORTERS GIVE US YOUR SUPPORT If you'd like everyone, everywhere to have a chance to discover opera. If you'd like them to revel in the feelings, the emotions and the thrills. If you'd like to share in our values and history. If you'd like to be part of a living, top-flight opera house that reaches out to the world. So that we can all enjoy the Liceu together and be the stars of the cast. Get in touch and we'll tell you how: Sponsorship Service 93 485 86 31 / [email protected] liceubarcelona.cat/donans-suport COLLABORATORS AMICS BENEFACTORS Angelini Cementos Molins GiS Mandarin Oriental, Amics de l'Òpera Carlos Garcés Núria Oliveras Axis Corporate Cinesa Gramona Barcelona de Tarragona Àngels Garcia Antoni Planas Banco Mediolanum Coca-Cola Happy Click Port de Barcelona Juan José Araúna Anna M. Garcia M. del Pilar Pons BASF Dilograf Illy Caffè Rolex Ramon Bassas Carme Garriga Rosa M. Provencio Bon Preu Eurofragance Jarclos Segur Ibérica Amèlia Bataller F. Xavier Garriga Pura Puchal Caixa d’Enginyers Fundación Loewe Koobin Serunion Montserrat Baulenas Ezequiel Giró Encarna Roca Catalana Occident Genebre-Hobby Flower Lavinia Sogeur Manuel Bertran Joan Gonzàlez Josep Roca Cellnex Telecom GFT Nationale Suisse Sumarroca Montserrat Boix Jaume Graell M. Carme Rusiñol Tradisa Beatriz Bonet Montserrat Grifell M. del Carmen Sáez Sebastià Borràs Eulàlia Juncosa Anna M. Sagarra M. Àngels Bosch Tomàs Llusera Montserrat Sirera BENEFACTORS José Ignacio Brugarolas Javier Lozano Maria Soldevila Josep Brustenga Mercè Mata Jaume Subirà Carlos Abril Manuel Crehuet Pere Grau Miquel Roca Manuel Busquet M. -

Original Instruments

7778.02 cover.qxp_CDS 7764 cover.qxd 31/10/2018 13:54 Page 1 CDS7778.02 Dynamic Srl Via Mura Chiappe 39, 16136 Genova - Italy tel.+39 010.27.22.884 fax +39 010.21.39.37 [email protected] visit us at www.dynamic.it DynamicOperaClassic Dynamic opera and classical music ORIGINAL INSTRUMENTS 7778.02 booklet.qxp_550 booklet.qxd 31/10/2018 15:41 Page 1 CDS7778.02 (DDD) ANTONIO VIVALDI (Venice, 1678 - Vienna, 1741) La Stravaganza - 12 Violin Concertos Op. IV Tot. Running Time 51:41 Concerto No. 1 in B flat major RV 383a 07:54 1 Allegro 02:55 2 Largo 02:35 3 Allegro 02:24 Concerto No. 2 in E minor RV 279 09:23 4 Allegro 03:58 5 Largo 02:24 6 Allegro 03:01 Concerto No. 3 in G major RV 301 08:22 7 Allegro 02:45 8 Largo 02:44 9 Allegro assai 02:53 Concerto No. 4 in A minor RV 357 07:58 10 Allegro 02:42 11 Grave 02:52 12 Allegro 02:24 7778.02 booklet.qxp_550 booklet.qxd 31/10/2018 15:41 Page 2 Concerto No. 5 in A major RV 347 08:56 13 Allegro 03:32 14 Largo 02:15 15 Allegro 03:09 Concerto No. 6 in G minor RV 316a 08:59 16 Allegro 02:32 17 Largo 02:57 18 Allegro 03:30 Tot. Running Time 45:27 Concerto No. 7 in C major RV 185 07:19 01 Largo 01:54 02 Allegro 02:06 03 Largo 01:22 04 Allegro 01:57 Concerto No. -

Studi Vivaldiani 19

ISTITUTO ITALIANO ANTONIO VIVALDI STUDI VIVALDIANI 19 – 2019 FONDAZIONE GIORGIO CINI VENEZIA STUDI VIVALDIANI Rivista annuale dell’Istituto Italiano Antonio Vivaldi della Fondazione Giorgio Cini Direttore Francesco Fanna Condirettore Michael Talbot Comitato scientifico Alessandro Borin Paul Everett Karl Heller Federico Maria Sardelli Eleanor Selfridge‑Field Roger‑Claude Travers Traduzioni: Alessandro Borin e Michael Talbot Redazione: Margherita Gianola Impaginazione: Tommaso Maggiolo Direttore responsabile: Gilberto Pizzamiglio Istituto Italiano Antonio Vivaldi Fondazione Giorgio Cini Isola di San Giorgio Maggiore 30124 Venezia (Italia) www.cini.it e‑mail: [email protected] Registrazione del Tribunale di Venezia n. 8 del 10 dicembre 2016 ISSN 1594‑0012 Aurelia Ambrosiano LA VERA IDENTITÀ DEL «MAR[QUIS] DU TOUREIL», DEDICATARIO DELLA SERENATA À 3 DI ANTONIO VIVALDI 1. INTRODUZIONE La Serenata à 3, RV 690, nota anche con l’incipit «Mio cor, povero cor», compo‑ sta da Antonio Vivaldi presumibilmente verso la fine della seconda decade del Settecento, è dedicata al «Mar[quis] du Toureil». Nel 1982 Michael Talbot, in un articolo sulle serenate vivaldiane, avanzò l’ipotesi – accolta con favore dagli stu‑ diosi e fino a oggi mai confutata – che il misterioso dedicatario fosse identificabile con l’abate tolosano Jean de Tourreil e che il testo della serenata fosse l’allegoria del processo cui fu sottoposto per ordine del Sant’Uffizio romano a causa della sua affiliazione al giansenismo.1 Recenti studi, però, hanno rivelato che tra il 1715 e il 1726 a Venezia visse un certo marchese «Anna Marco de Torel», cavaliere francese, che nell’autunno del 1717 tenne a battesimo Daniel Mauro, nipote di Antonio Vivaldi, nato dal matri‑ monio tra Cecilia, sorella del compositore, e il copista di musica Giovanni Antonio.2 Il suo nome esatto era Anne‑Marc Goislard du Toureil e certamente questi è il «Mar[quis] du Toureil» citato da Antonio Vivaldi sul frontespizio della Serenata à 3.