Susan Schneider

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17. Idealism, Or Something Near Enough Susan Schneider (In

17. Idealism, or Something Near Enough Susan Schneider (In Pearce and Goldsmidt, OUP, in press.) Some observations: 1. Mathematical entities do not come for free. There is a field, philosophy of mathematics, and it studies their nature. In this domain, many theories of the nature of mathematical entities require ontological commitments (e.g., Platonism). 2. Fundamental physics (e.g., string theory, quantum mechanics) is highly mathematical. Mathematical entities purport to be abstract—they purport to be non-spatial, atemporal, immutable, acausal and non-mental. (Whether they truly are abstract is a matter of debate, of course.) 3. Physicalism, to a first approximation, holds that everything is physical, or is composed of physical entities. 1 As such, physicalism is a metaphysical hypothesis about the fundamental nature of reality. In Section 1 of this paper, I urge that it is reasonable to ask the physicalist to inquire into the nature of mathematical entities, for they are doing heavy lifting in the physicalist’s approach, describing and identifying the fundamental physical entities that everything that exists is said to reduce to (supervene on, etc.). I then ask whether the physicalist in fact has the resources to provide a satisfying account of the nature of these mathematical entities, given existing work in philosophy of mathematics on nominalism and Platonism that she would likely draw from. And the answer will be: she does not. I then argue that this deflates the physicalist program, in significant ways: physicalism lacks the traditional advantages of being the most economical theory, and having a superior story about mental causation, relative to competing theories. -

Comment Attachment

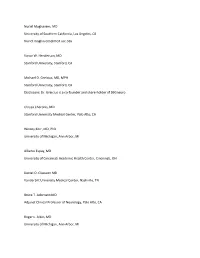

Nuriel Moghavem, MD University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA [email protected] Victor W. Henderson, MD Stanford University, Stanford, CA Michael D. Greicius, MD, MPH Stanford University, Stanford, CA Disclosure: Dr. Greicius is a co-founder and share-holder of SBGneuro Chrysa Cheronis, MD Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, CA Wesley Kerr, MD, PhD University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI Alberto Espay, MD University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center, Cincinnati, OH Daniel O. Claassen MD Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN Bruce T. Adornato MD Adjunct Clinical Professor of Neurology, Palo Alto, CA Roger L. Albin, MD University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI R. Ryan Darby, MD Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN Graham Garrison, MD University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio Lina Chervak, MD University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH Abhimanyu Mahajan, MD, MHS Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL Richard Mayeux, MD Columbia University, New York, NY Lon Schneider MD Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CAv Sami Barmada, MD PhD University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI Evan Seevak, MD Alameda Health System, Oakland, CA Will Mantyh MD University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN Bryan M. Spann, DO, PhD Consultant, Cognitive and Neurobehavior Disorders, Scottsdale, AZ Kevin Duque, MD University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH Lealani Mae Acosta, MD, MPH Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN Marie Adachi, MD Alameda Health System, Oakland, CA Marina Martin, MD, MPH Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA Matthew Schrag MD, PhD Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN Matthew L. Flaherty, MD University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH Stephanie Reyes, MD Durham, NC Hani Kushlaf, MD University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH David B Clifford, MD Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, Missouri Marc Diamond, MD UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX Disclosure: Dr. -

European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy, IV-2 | 2012 Darwinized Hegelianism Or Hegelianized Darwinism? 2

European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy IV-2 | 2012 Wittgenstein and Pragmatism Darwinized Hegelianism or Hegelianized Darwinism? Mathias Girel Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/736 DOI: 10.4000/ejpap.736 ISSN: 2036-4091 Publisher Associazione Pragma Electronic reference Mathias Girel, « Darwinized Hegelianism or Hegelianized Darwinism? », European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy [Online], IV-2 | 2012, Online since 24 December 2012, connection on 21 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/736 ; DOI : 10.4000/ejpap.736 This text was automatically generated on 21 April 2019. Author retains copyright and grants the European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Darwinized Hegelianism or Hegelianized Darwinism? 1 Darwinized Hegelianism or Hegelianized Darwinism? Mathias Girel 1 It has been said that Peirce was literally talking “with the rifle rather than with the shot gun or water hose” (Perry 1935, vol. 2: 109). Readers of his review of James’s Principles can easily understand why. In some respects, the same might be true of the series of four books Joseph Margolis has been devoting to pragmatism since 2000. One of the first targets of Margolis’s rereading was the very idea of a ‘revival’ of pragmatism (a ‘revival’ of something that never was, in some ways), and, with it, the idea that the long quarrel between Rorty and Putnam was really a quarrel over pragmatism (that is was a pragmatist revival, in some ways). The uncanny thing is that, the more one read the savory chapters of the four books, the more one feels that the hunting season is open, but that the game is not of the usual kind and looks more like zombies, so to speak. -

Living in a Matrix, She Thinks to Herself

y most accounts, Susan Schneider lives a pretty normal life. BAn assistant professor of LIVING IN philosophy, she teaches classes, writes academic papers and A MATrix travels occasionally to speak at a philosophy or science lecture. At home, she shuttles her daughter to play dates, cooks dinner A PHILOSOPHY and goes mountain biking. ProfESSor’S LifE in Then suddenly, right in the middle of this ordinary American A WEB OF QUESTIONS existence, it happens. Maybe we’re all living in a Matrix, she thinks to herself. It’s like in the by Peter Nichols movie when the question, What is the Matrix? keeps popping up on Neo’s computer screen and sets him to wondering. Schneider starts considering all the what-ifs and the maybes that now pop up all around her. Maybe the warm sun on my face, the trees swishing by and the car I’m driving down the road are actually code streaming through the circuits of a great computer. What if this world, which feels so compellingly real, is only a simulation thrown up by a complex and clever computer game? If I’m in it, how could I even know? What if my real- seeming self is nothing more than an algorithm on a computational network? What if everything is a computer-generated dream world – a momentary assemblage of information clicking and switching and running away on a grid laid down by some advanced but unknown intelligence? It’s like that time, after earning an economics degree as an undergrad at Berkeley, she suddenly switched to philosophy. -

A Diatribe on Jerry Fodor's the Mind Doesn't Work That Way1

PSYCHE: http://psyche.cs.monash.edu.au/ Yes, It Does: A Diatribe on Jerry Fodor’s The Mind Doesn’t Work that Way1 Susan Schneider Department of Philosophy University of Pennsylvania 423 Logan Hall 249 S. 36th Street Philadelphia, PA 19104-6304 [email protected] © S. Schneider 2007 PSYCHE 13 (1), April 2007 REVIEW OF: J. Fodor, 2000. The Mind Doesn’t Work that Way. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 144 pages, ISBN-10: 0262062127 Abstract: The Mind Doesn’t Work That Way is an expose of certain theoretical problems in cognitive science, and in particular, problems that concern the Classical Computational Theory of Mind (CTM). The problems that Fodor worries plague CTM divide into two kinds, and both purport to show that the success of cognitive science will likely be limited to the modules. The first sort of problem concerns what Fodor has called “global properties”; features that a mental sentence has which depend on how the sentence interacts with a larger plan (i.e., set of sentences), rather than the type identity of the sentence alone. The second problem concerns what many have called, “The Relevance Problem”: the problem of whether and how humans determine what is relevant in a computational manner. However, I argue that the problem that Fodor believes global properties pose for CTM is a non-problem, and that further, while the relevance problem is a serious research issue, it does not justify the grim view that cognitive science, and CTM in particular, will likely fail to explain cognition. 1. Introduction The current project, it seems to me, is to understand what various sorts of theories of mind can and can't do, and what it is about them in virtue of which they can or can't do it. -

Reflexive Monism

Reflexive Monism Max Velmans, Goldsmiths, University of London; email [email protected]; http://www.goldsmiths.ac.uk/psychology/staff/velmans.php Journal of Consciousness Studies (2008), 15(2), 5-50. Abstract. Reflexive monism is, in essence, an ancient view of how consciousness relates to the material world that has, in recent decades, been resurrected in modern form. In this paper I discuss how some of its basic features differ from both dualism and variants of physicalist and functionalist reductionism, focusing on those aspects of the theory that challenge deeply rooted presuppositions in current Western thought. I pay particular attention to the ontological status and seeming “out- thereness” of the phenomenal world and to how the “phenomenal world” relates to the “physical world”, the “world itself”, and processing in the brain. In order to place the theory within the context of current thought and debate, I address questions that have been raised about reflexive monism in recent commentaries and also evaluate competing accounts of the same issues offered by “transparency theory” and by “biological naturalism”. I argue that, of the competing views on offer, reflexive monism most closely follows the contours of ordinary experience, the findings of science, and common sense. Key words: Consciousness, reflexive, monism, dualism, reductionism, physicalism, functionalism, transparency, biological naturalism, phenomenal world, physical world, world itself, universe itself, brain, perceptual projection, phenomenal space, measured space, physical space, space perception, information, virtual reality, hologram, phenomenological internalism, phenomenological externalism, first person, third person, complementary What is Reflexive Monism? Monism is the view that the universe, at the deepest level of analysis, is one thing, or composed of one fundamental kind of stuff. -

Searle's Biological Naturalism and the Argument from Consciousness

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 15 Issue 1 Article 5 1-1-1998 Searle's Biological Naturalism and the Argument from Consciousness J.P. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Moreland, J.P. (1998) "Searle's Biological Naturalism and the Argument from Consciousness," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 15 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. DOI: 10.5840/faithphil19981513 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol15/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. SEARLE'S BIOLOGICAL NATURALISM AND THE ARGUMENT FROM CONSCIOUSNESS J. P. Moreland In recent years, Robert Adams and Richard Swinburne have developed an argument for God's existence from the reality of mental phenomena. Call this the argument from consciousness (AC). My purpose is to develop and defend AC and to use it as a rival paradigm to critique John Searle's biological natural ism. The article is developed in three steps. First, two issues relevant to the epistemic task of adjudicating between rival scientific paradigms (basicality and naturalness) are clarified and illustrated. Second, I present a general ver sion of AC and identify the premises most likely to come under attack by philosophical naturalists. Third, I use the insights gained in steps one and two to criticize Searle's claim that he has developed an adequate naturalistic theory of the emergence of mental entities. -

A Traditional Scientific Perspective on the Integrated Information Theory Of

entropy Article A Traditional Scientific Perspective on the Integrated Information Theory of Consciousness Jon Mallatt The University of Washington WWAMI Medical Education Program at The University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844, USA; [email protected] Abstract: This paper assesses two different theories for explaining consciousness, a phenomenon that is widely considered amenable to scientific investigation despite its puzzling subjective aspects. I focus on Integrated Information Theory (IIT), which says that consciousness is integrated information (as φMax) and says even simple systems with interacting parts possess some consciousness. First, I evaluate IIT on its own merits. Second, I compare it to a more traditionally derived theory called Neurobiological Naturalism (NN), which says consciousness is an evolved, emergent feature of complex brains. Comparing these theories is informative because it reveals strengths and weaknesses of each, thereby suggesting better ways to study consciousness in the future. IIT’s strengths are the reasonable axioms at its core; its strong logic and mathematical formalism; its creative “experience- first” approach to studying consciousness; the way it avoids the mind-body (“hard”) problem; its consistency with evolutionary theory; and its many scientifically testable predictions. The potential weakness of IIT is that it contains stretches of logic-based reasoning that were not checked against hard evidence when the theory was being constructed, whereas scientific arguments require such supporting evidence to keep the reasoning on course. This is less of a concern for the other theory, NN, because it incorporated evidence much earlier in its construction process. NN is a less mature theory than IIT, less formalized and quantitative, and less well tested. -

Lecture 24 Biological Naturalism About the Lecture

Lecture 24 Biological Naturalism About the Lecture: Biological naturalism is a philosophical theory of the mind. Itputs the problem of mind-body dualism and the related context of consciousness in a new perspective. It provides a broad naturalistic framework for the explanation of consciousness and other mental phenomena. The theory is based on the hypothesis that mental phenomena are caused by and realized in the brain processes.This theory is a part of a biological worldview and this worldview is based on the theory of evolution. The human life is manifested in the evolutionary process of the universe. On the other hand, the natural aspect of the theory shows that the brain, as the central part of the human organism causes mental life. The mental life is comprised of both conscious and unconscious activities of the brain. The conscious aspects include conscious and unconscious mental states along with their basic features, like intentionality, subjectivity, free will, etc. whereas the unconscious aspects of brain signify its neurophysiological functions. Key words: Naturalism, Mind-Body Dualism, Causal Relation, Emergence, Micro and macro level. Biological naturalism as a theory of mind puts the problem of mind-body dualism and the related context of consciousness in a new perspective. It provides a broad naturalistic framework for the explanation of consciousness and other mental phenomena. The theory is based on the hypothesis that mental phenomena are caused by and realized in the brain processes. Moreover, as Searle defines his theory, “Mental phenomena are caused by the neurophysiological processes in the brain and are themselves features of the brain. -

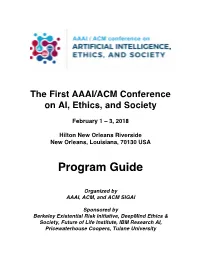

Program Guide

The First AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society February 1 – 3, 2018 Hilton New Orleans Riverside New Orleans, Louisiana, 70130 USA Program Guide Organized by AAAI, ACM, and ACM SIGAI Sponsored by Berkeley Existential Risk Initiative, DeepMind Ethics & Society, Future of Life Institute, IBM Research AI, Pricewaterhouse Coopers, Tulane University AIES 2018 Conference Overview Thursday, February Friday, Saturday, 1st February 2nd February 3rd Tulane University Hilton Riverside Hilton Riverside 8:30-9:00 Opening 9:00-10:00 Invited talk, AI: Invited talk, AI Iyad Rahwan and jobs: and Edmond Richard Awad, MIT Freeman, Harvard 10:00-10:15 Coffee Break Coffee Break 10:15-11:15 AI session 1 AI session 3 11:15-12:15 AI session 2 AI session 4 12:15-2:00 Lunch Break Lunch Break 2:00-3:00 AI and law AI and session 1 philosophy session 1 3:00-4:00 AI and law AI and session 2 philosophy session 2 4:00-4:30 Coffee break Coffee Break 4:30-5:30 Invited talk, AI Invited talk, AI and law: and philosophy: Carol Rose, Patrick Lin, ACLU Cal Poly 5:30-6:30 6:00 – Panel 2: Invited talk: Panel 1: Prioritizing The Venerable What will Artificial Ethical Tenzin Intelligence bring? Considerations Priyadarshi, in AI: Who MIT Sets the Standards? 7:00 Reception Conference Closing reception Acknowledgments AAAI and ACM acknowledges and thanks the following individuals for their generous contributions of time and energy in the successful creation and planning of AIES 2018: Program Chairs: AI and jobs: Jason Furman (Harvard University) AI and law: Gary Marchant -

The Logical Foundations of Democratic Dogma' I

THE LOGICAL FOUNDATIONS OF DEMOCRATIC DOGMA’ I SCIENCE AND MAN: THE DEGRADATION OF SCIENTIFIC DOGMA I. INTRODUCTION A are doubtless wondering why, in this time of stress Youand strain, a philosopher of all men should be asked to speak to you. And you have a right to wonder. If, as the ancient Roman dictum has it, inter arma leges silent, even more in such times should the philosopher withdraw into silence and leave the field to better men. For this is not the time, it will be said, for abstract thought and balanced judg- ment, but for emotion and action. And yet a strong case can be made out for the opposite. If in time of war laws are silent it is just at such a time that the law should speak most majestically. If in time of war unreason is in the saddle it is at such a time that man, if he is to remain man and not sink to the level of the beast, should think most about reason and rationality. “The philosopher,” wrote William James, “is simply a man who thinks a little more stubbornly than other people.” It is, however, not merely this stubbornness that distin- guishes the philosopher but rather what all his stubborn- 1A course of three public lectures delivered at the Rice Institute, February 22, 24, and 26, 191.3, by Wilbur Marshall Urban, Dr. Phil., L.H.D., Pro- fessor of Philosophy, Emeritus, at Yale University. COPYRIGHT 1943, THE RICE INSTITUTE 69 70 Foundations of Democratic Dogma ness is about. The scientist discovering a new law, the in- ventor perfecting a new instrument of beneficence or malefi- cence-the administrator, the industrialist-all these think very hard about many important things. -

1 Why I Am Not a Property Dualist by John R. Searle I Have Argued in a Number of Writings1 That the Philosophical Part (Though

1 Why I Am Not a Property Dualist By John R. Searle I have argued in a number of writings1 that the philosophical part (though not the neurobiological part) of the traditional mind-body problem has a fairly simple and obvious solution: All of our mental phenomena are caused by lower level neuronal processes in the brain and are themselves realized in the brain as higher level, or system, features. The form of causation is “bottom up,” whereby the behavior of lower level elements, presumably neurons and synapses, causes the higher level or system features of consciousness and intentionality. (This form of causation, by the way, is common in nature; for example, the higher level feature of solidity is causally explained by the behavior of the lower level elements, the molecules.) Because this view emphasizes the biological character of the mental, and because it treats mental phenomena as ordinary parts of nature, I have labeled it “biological naturalism.” To many people biological naturalism looks a lot like property dualism. Because I believe property dualism is mistaken, I would like to try to clarify the differences between the two accounts and try to expose the weaknesses in property dualism. This short paper then has the two subjects expressed by the double meanings in its title: why my views are not the same as property dualism, and why I find property dualism unacceptable. There are, of course, several different “mind-body” problems. The one that most concerns me in this article is the relationship between consciousness and brain processes. I think that the conclusions of the discussion will extend to other features of the mind-body problem, such as, for example, the relationship between intentionality and brain processes, but for the sake of simplicity I will concentrate on consciousness.