Benzodiazepines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Once-Daily Skeletal Muscle Relaxant in SA

NEWS Once-daily skeletal muscle relaxant in SA Myprocam (cyclobenzaprine with spine-related disorders and other 8. What are the classes of muscle a protective coating, and a polymer extended release [ER] sports injuries are excellent candidates relaxants? membrane that controls the rate of hydrochloride) is the most widely for Myprocam. Skeletal muscle relaxants (SMRs) are drug release. prescribed skeletal muscle a group of structurally unrelated drugs, The formulation of the drug relaxant in the US, is now available 4. What are the common as shown in Figure 1. These are divided ensures early systemic exposure in SA. Myprocam’s safety and efficacy indications for which Myprocam into two categories: to cyclobenzaprine, with a plasma has been shown in more than 20 clinical is used, and what are the common • Antispasticity agents: Used to concentration at four hours that trials. It was recently launched by causes of these ailments? treat muscle spasticity caused by is similar to that observed with Adcock Ingram nationally, making SA Low back pain, neck pain, sports traumatic neurologic injury, multiple cyclobenzaprine IR. the second country (only to the US) to injuries, muscle sprains and strains. sclerosis, and other conditions. However, in contrast to the bring the product to market. Common causes of these conditions • Antispasmodic agents: Used fluctuating peaks and troughs in Myprocam, indicated for the relief of include sports injuries, car accidents, to treat muscular pain or spasm plasma cyclobenzaprine concentration muscle spasm associated with acute work-related injuries, and everyday associated with acute, nonspecific after administration of the IR and painful musculoskeletal conditions, activities, which account for acute musculoskeletal conditions. -

Analysis of a Benzodiazepine-Based Drug Using GC-MS 28

LAAN-E-MS-E028 GCMS Gas Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer Analysis of a Benzodiazepine-Based Drug Using GC-MS 28 Benzodiazepine drugs are commonly used in sleeping aids and tranquilizers, and sometimes in crimes or suicide. Therefore, these chemical substances are often analyzed by forensic laboratories for criminal or academic investigations. This datasheet shows the results from using GC-MS to measure 9 types of benzodiazepine drugs. Analysis Conditions Table 1: Analysis Conditions GC-MS :GCMS-QP2010 Ultra Column : Rxi®-5Sil MS (30 mL. X 0.25 mmI.D., df=0.25 µm, Shimadzu GLC P/N:13623) Glass insert :Silanized splitless insert (P/N: 221-48876-03) [GC] [MS] Vaporization chamber temperature : 260℃ Interface temperature : 280℃ Column oven temperature : 60℃ (2min) -> (10℃/min) -> 320℃ (10min) Ion source temperature : 200℃ Injection mode : Splitless Solvent elution time : 2.0 min Sampling time : 1 min Measurement mode : Scan High pressure injection method: 250 kPa (1.5 min) Mass range : m/z 35-600 Carrier gas : Helium Event time : 0.3 sec Control mode :Linear velocity (45.6 cm/sec) Emission current : 150 µA (high sensitivity) Purge flow rate :3.0 ml/min Sample injection quantity :1.0 µL (x1,000,000) 3.0 3 2.5 2 2.0 1.5 1.0 1 0.5 22.0 23.0 24.0 25.0 26.0 27.0 28.0 min % % 312 55 100.0 1 285 100.0 2 313 109 75.0 75.0 266 259287 342 166 50.0 238 50.0 248 25.0 183 25.0 63 109 0.0 0.0 100 200 300 400 100 200 300 400 % 86 100.0 3 75.0 50.0 25.0 58 99 183 315 387 0.0 100 200 300 400 Fig. -

Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Fentanyl and Its Analogues in Biological Specimens

Recommended methods for the Identification and Analysis of Fentanyl and its Analogues in Biological Specimens MANUAL FOR USE BY NATIONAL DRUG ANALYSIS LABORATORIES Laboratory and Scientific Section UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Fentanyl and its Analogues in Biological Specimens MANUAL FOR USE BY NATIONAL DRUG ANALYSIS LABORATORIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2017 Note Operating and experimental conditions are reproduced from the original reference materials, including unpublished methods, validated and used in selected national laboratories as per the list of references. A number of alternative conditions and substitution of named commercial products may provide comparable results in many cases. However, any modification has to be validated before it is integrated into laboratory routines. ST/NAR/53 Original language: English © United Nations, November 2017. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of names of firms and commercial products does not imply the endorse- ment of the United Nations. This publication has not been formally edited. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Acknowledgements The Laboratory and Scientific Section of the UNODC (LSS, headed by Dr. Justice Tettey) wishes to express its appreciation and thanks to Dr. Barry Logan, Center for Forensic Science Research and Education, at the Fredric Rieders Family Founda- tion and NMS Labs, United States; Amanda L.A. -

124.210 Schedule IV — Substances Included. 1

1 CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES, §124.210 124.210 Schedule IV — substances included. 1. Schedule IV shall consist of the drugs and other substances, by whatever official name, common or usual name, chemical name, or brand name designated, listed in this section. 2. Narcotic drugs. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation containing any of the following narcotic drugs, or their salts calculated as the free anhydrous base or alkaloid, in limited quantities as set forth below: a. Not more than one milligram of difenoxin and not less than twenty-five micrograms of atropine sulfate per dosage unit. b. Dextropropoxyphene (alpha-(+)-4-dimethylamino-1,2-diphenyl-3-methyl-2- propionoxybutane). c. 2-[(dimethylamino)methyl]-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol, its salts, optical and geometric isomers and salts of these isomers (including tramadol). 3. Depressants. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation which contains any quantity of the following substances, including its salts, isomers, and salts of isomers whenever the existence of such salts, isomers, and salts of isomers is possible within the specific chemical designation: a. Alprazolam. b. Barbital. c. Bromazepam. d. Camazepam. e. Carisoprodol. f. Chloral betaine. g. Chloral hydrate. h. Chlordiazepoxide. i. Clobazam. j. Clonazepam. k. Clorazepate. l. Clotiazepam. m. Cloxazolam. n. Delorazepam. o. Diazepam. p. Dichloralphenazone. q. Estazolam. r. Ethchlorvynol. s. Ethinamate. t. Ethyl Loflazepate. u. Fludiazepam. v. Flunitrazepam. w. Flurazepam. x. Halazepam. y. Haloxazolam. z. Ketazolam. aa. Loprazolam. ab. Lorazepam. ac. Lormetazepam. ad. Mebutamate. ae. Medazepam. af. Meprobamate. ag. Methohexital. ah. Methylphenobarbital (mephobarbital). -

S1 Table. List of Medications Analyzed in Present Study Drug

S1 Table. List of medications analyzed in present study Drug class Drugs Propofol, ketamine, etomidate, Barbiturate (1) (thiopental) Benzodiazepines (28) (midazolam, lorazepam, clonazepam, diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, oxazepam, potassium Sedatives clorazepate, bromazepam, clobazam, alprazolam, pinazepam, (32 drugs) nordazepam, fludiazepam, ethyl loflazepate, etizolam, clotiazepam, tofisopam, flurazepam, flunitrazepam, estazolam, triazolam, lormetazepam, temazepam, brotizolam, quazepam, loprazolam, zopiclone, zolpidem) Fentanyl, alfentanil, sufentanil, remifentanil, morphine, Opioid analgesics hydromorphone, nicomorphine, oxycodone, tramadol, (10 drugs) pethidine Acetaminophen, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (36) (celecoxib, polmacoxib, etoricoxib, nimesulide, aceclofenac, acemetacin, amfenac, cinnoxicam, dexibuprofen, diclofenac, emorfazone, Non-opioid analgesics etodolac, fenoprofen, flufenamic acid, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, (44 drugs) ketoprofen, ketorolac, lornoxicam, loxoprofen, mefenamiate, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, oxaprozin, piroxicam, pranoprofen, proglumetacin, sulindac, talniflumate, tenoxicam, tiaprofenic acid, zaltoprofen, morniflumate, pelubiprofen, indomethacin), Anticonvulsants (7) (gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, valproic acid, lacosamide) Vecuronium, rocuronium bromide, cisatracurium, atracurium, Neuromuscular hexafluronium, pipecuronium bromide, doxacurium chloride, blocking agents fazadinium bromide, mivacurium chloride, (12 drugs) pancuronium, gallamine, succinylcholine -

Drug Screening: Actual Status, Pitfalls and Suggestions for Improvement Drogenscreening: Gegenwa¨ Rtiger Stand, Fehlermo¨ Glichkeiten Und Verbesserungsvorschla¨Ge

J Lab Med 2004;28(4):317–325 ᮊ 2004 by Walter de Gruyter • Berlin • New York 2004/03304 Drug Monitoring und Toxikologie Redaktion: V. W. Armstrong Drug screening: Actual status, pitfalls and suggestions for improvement Drogenscreening: Gegenwa¨ rtiger Stand, Fehlermo¨ glichkeiten und Verbesserungsvorschla¨ge Wolf R. Ku¨ lpmann* pretierbar. In Wirklichkeit mu¨ ssen viele Aspekte beru¨ ck- sichtigt werden, um einen aussagekra¨ ftigen Befund zu Klinische Chemie, Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, erhalten, z.B. Pra¨ analytik, Spezifita¨ t und Empfindlichkeit Hannover, Germany des Verfahrens oder Qualita¨ tssicherung. Obwohl die Abstract mechanisierten Meßverfahren naturgema¨ ß quantitative Ergebnisse liefern, wird aufgezeigt, daß es sich in der Immunoassays for drug screening are often regarded as Regel empfiehlt, qualitative Befunde zu erstellen. Die procedures which are easily performed and interpreted. Verfahren erlauben aber im Gegensatz zu den auch fu¨r But in fact, many aspects have to be considered to diese Zwecke verwendeten Teststreifen die Entschei- obtain a meaningful result. Among these are sampling, dungsgrenze (cut-off) der jeweiligen Fragestellung anzu- specificity and sensitivity of assays, and quality assess- passen, z.B. bei akuter Intoxikation, chronischem Abusus ment. Although the mechanised procedures yield quan- oder U¨ berwachung des Drogenentzugs. titative results, there are good reasons to generally report Ein schwerwiegender Nachteil von Immunoassays zum qualitative findings. The mechanised procedures allow Nachweis von Amphetamin und a¨ hnlichen Substanzen, the adjustment of the cut-off concentration to the clinical Barbituraten, Benzodiazepinen und Opiaten besteht dar- setting, e.g. in the case of acute intoxication, chronic in, daß eine starke Kreuzreaktivita¨ t des Antiko¨ rpers abuse or drug withdrawal, an important advantage as gegenu¨ ber pharmakologisch wenig wirksamen Verbin- compared to test strips. -

Medications in Long-Term Care: When Less Is More

Medications in Long-Term Care: When Less is More a, b,c Thomas W. Meeks, MD *, John W. Culberson, MD , d,e Monica S. Horton, MD, MSc KEYWORDS Long-term care Inappropriate prescribing Polypharmacy Psychotropics Opiates Sedatives HISTORY OF MEDICATION REDUCTION IN LONG-TERM CARE The Nursing Home Reform Act (OBRA-87) enacted in 1987 called for sweeping changes in the standards of care in nursing homes in accordance with new, more demanding federal regulations. For example, OBRA-87 called for a new approach to the use of antipsychotics in persons with dementia. Because antipsychotics were regarded as frequently inappropriate chemical restraints in long-term care (LTC), OBRA-87 mandated dose reductions in antipsychotics in an effort to discontinue them whenever possible. OBRA-87 proposed that a safer, more supportive environ- ment in LTC settings would facilitate such reductions in antipsychotic doses.1 Overall rates of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults have ranged from 12% to 40%, depending on the setting, criteria, and population sampled.2 Devel- oping from burgeoning concerns for polypharmacy and potential iatrogenic toxicity of medication in older adults, expert consensus lists of potentially inappropriate pharma- cotherapy in the elderly (PIPE) began to emerge. In general, drugs with activity in the central nervous system (CNS) were commonly placed on these PIPE lists, and hence our focus on such medications in this review. This work was supported by the following Geriatric Academic Career Awards: (1) K01 HP00047-02 (Dr. Meeks) (2) K01 HP00080-02 (Dr. Culberson) (3) K01 HP00114-02 (Dr. Horton). The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. -

Drug Class Review on Skeletal Muscle Relaxants

Drug Class Review on Skeletal Muscle Relaxants Final Report Update 2 May 2005 Original Report Date: April 2003 Update 1 Report Date: January 2004 A literature scan of this topic is done periodically The purpose of this report is to make available information regarding the comparative effectiveness and safety profiles of different drugs within pharmaceutical classes. Reports are not usage guidelines, nor should they be read as an endorsement of, or recommendation for, any particular drug, use or approach. Oregon Health & Science University does not recommend or endorse any guideline or recommendation developed by users of these reports. Roger Chou, MD Kim Peterson, MS Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center Oregon Health & Science University Mark Helfand, MD, MPH, Director Copyright © 2005 by Oregon Health & Science University Portland, Oregon 97201. All rights reserved. Note: A scan of the medical literature relating to the topic is done periodically (see http://www.ohsu.edu/ohsuedu/research/policycenter/DERP/about/methods.cfm for scanning process description). Upon review of the last scan, the Drug Effectiveness Review Project governance group elected not to proceed with another full update of this report. Some portions of the report may not be up to date. Prior versions of this report can be accessed at the DERP website. Final Report Update 2 Drug Effectiveness Review Project TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................................4 Scope and -

CYCLOBENZAPRINE (Brand Name: Flexeril®, Amrix®)

Drug Enforcement Administration Diversion Control Division Drug & Chemical Evaluation Section CYCLOBENZAPRINE ® ® (Brand Name: Flexeril , Amrix ) March 2020 Introduction: Illicit Uses: Cyclobenzaprine is a central nervous system Anecdotal reports found on the Internet suggest (CNS) muscle relaxant intended for short-term use that individuals are taking cyclobenzaprine alone or in the treatment of pain, tenderness and limitation of in combination with other illicit drugs to produce or motion caused by muscle spasms. Cyclobenzaprine enhance psychoactive effects. Individuals have may enhance the effects of other CNS depressants reported taking cyclobenzadrine both orally and including alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines intra-nasally at doses ranging from 10 mg to 60 mg. and narcotics and anecdotal reports indicate it is Sedation, relaxation and increased heart rate were used non-medically to induce euphoria and the most common effects reported. Euphoria was relaxation. reported by a smaller number of individuals. Licit Uses: Illicit Distribution: Cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride is approved for Several indicators suggest that cyclobenzaprine use in the United States as a muscle relaxant. It is is being intentionally misused or abused. According marketed under the brand names Flexeril® and to the American Association of Poison Control Amrix® and as generic formulations in 5, 7.5, and 10 Centers, 10,615 case mentions and 4,444 single mg tablets intended for short-term (2 to 3 week) oral exposures were associated with cyclobenzaprine in administration. The usual starting dose is 5 mg, 2016, resulting in 75 major medical outcomes and three times per day. The maximum recommended four deaths among single substance exposures. In dose is 10 mg, three times daily. -

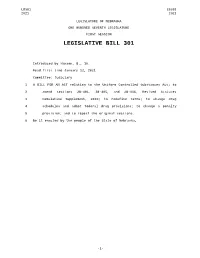

Introduced B.,Byhansen, 16

LB301 LB301 2021 2021 LEGISLATURE OF NEBRASKA ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH LEGISLATURE FIRST SESSION LEGISLATIVE BILL 301 Introduced by Hansen, B., 16. Read first time January 12, 2021 Committee: Judiciary 1 A BILL FOR AN ACT relating to the Uniform Controlled Substances Act; to 2 amend sections 28-401, 28-405, and 28-416, Revised Statutes 3 Cumulative Supplement, 2020; to redefine terms; to change drug 4 schedules and adopt federal drug provisions; to change a penalty 5 provision; and to repeal the original sections. 6 Be it enacted by the people of the State of Nebraska, -1- LB301 LB301 2021 2021 1 Section 1. Section 28-401, Revised Statutes Cumulative Supplement, 2 2020, is amended to read: 3 28-401 As used in the Uniform Controlled Substances Act, unless the 4 context otherwise requires: 5 (1) Administer means to directly apply a controlled substance by 6 injection, inhalation, ingestion, or any other means to the body of a 7 patient or research subject; 8 (2) Agent means an authorized person who acts on behalf of or at the 9 direction of another person but does not include a common or contract 10 carrier, public warehouse keeper, or employee of a carrier or warehouse 11 keeper; 12 (3) Administration means the Drug Enforcement Administration of the 13 United States Department of Justice; 14 (4) Controlled substance means a drug, biological, substance, or 15 immediate precursor in Schedules I through V of section 28-405. 16 Controlled substance does not include distilled spirits, wine, malt 17 beverages, tobacco, hemp, or any nonnarcotic substance if such substance 18 may, under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. -

Active Moiety Name FDA Established Pharmacologic Class (EPC) Text

FDA Established Pharmacologic Class (EPC) Text Phrase PLR regulations require that the following statement is included in the Highlights Indications and Usage heading if a drug is a member of an EPC [see 21 CFR 201.57(a)(6)]: “(Drug) is a (FDA EPC Text Phrase) indicated for [indication(s)].” For Active Moiety Name each listed active moiety, the associated FDA EPC text phrase is included in this document. For more information about how FDA determines the EPC Text Phrase, see the 2009 "Determining EPC for Use in the Highlights" guidance and 2013 "Determining EPC for Use in the Highlights" MAPP 7400.13. .alpha. -

Anaesthetic Implications of Calcium Channel Blockers

436 Anaesthetic implications of calcium channel Leonard C. Jenkins aA MD CM FRCPC blockers Peter J. Scoates a sc MD FRCPC CONTENTS The object of this review is to emphasize the anaesthetic implications of calcium channel block- Physiology - calcium/calcium channel blockers Uses of calcium channel blockers ers for the practising anaesthetist. These drugs have Traditional played an expanding role in therapeutics since their Angina pectoris introduction and thus anaesthetists can expect to see Arrhythmias increasing numbers of patients presenting for anaes- Hypertension thesia who are being treated with calcium channel Newer and investigational Cardiac blockers. Other reviews have emphasized the basic - Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pharmacology of calcium channel blockers. 1-7 - Cold cardioplegia - Pulmonary hypertension Physiology - calcium/calcium channel blockers Actions on platelets Calcium plays an important role in many physio- Asthma Obstetrics logical processes, such as blood coagulation, en- - Premature labor zyme systems, muscle contraction, bone metabo- - Pre-eclampsia lism, synaptic transmission, and cell membrane Achalasia and oesophageal spasm excitability. Especially important is the role of Increased intraocular pressure therapy calcium in myocardial contractility and conduction Protective effect on kidney after radiocontrast Cerebral vasospasm as well as in vascular smooth muscle reactivity. 7 Induced hypotensive anaesthesia Thus, it can be anticipated that any drug interfering Drag interactions with calcium channel blockers with the action of calcium could have widespread With anaesthetic agents effects. Inhalation agents In order to understand the importance of calcium - Effect on haemodynamics - Effect on MAC in cellular excitation, it is necessary to review some Neuromuscular blockers membrane physiology. Cell membranes are pri- Effects on epinephrine-induced arrhythmias marily phospholipids arranged in a bilayer.