Medications in Long-Term Care: When Less Is More

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Once-Daily Skeletal Muscle Relaxant in SA

NEWS Once-daily skeletal muscle relaxant in SA Myprocam (cyclobenzaprine with spine-related disorders and other 8. What are the classes of muscle a protective coating, and a polymer extended release [ER] sports injuries are excellent candidates relaxants? membrane that controls the rate of hydrochloride) is the most widely for Myprocam. Skeletal muscle relaxants (SMRs) are drug release. prescribed skeletal muscle a group of structurally unrelated drugs, The formulation of the drug relaxant in the US, is now available 4. What are the common as shown in Figure 1. These are divided ensures early systemic exposure in SA. Myprocam’s safety and efficacy indications for which Myprocam into two categories: to cyclobenzaprine, with a plasma has been shown in more than 20 clinical is used, and what are the common • Antispasticity agents: Used to concentration at four hours that trials. It was recently launched by causes of these ailments? treat muscle spasticity caused by is similar to that observed with Adcock Ingram nationally, making SA Low back pain, neck pain, sports traumatic neurologic injury, multiple cyclobenzaprine IR. the second country (only to the US) to injuries, muscle sprains and strains. sclerosis, and other conditions. However, in contrast to the bring the product to market. Common causes of these conditions • Antispasmodic agents: Used fluctuating peaks and troughs in Myprocam, indicated for the relief of include sports injuries, car accidents, to treat muscular pain or spasm plasma cyclobenzaprine concentration muscle spasm associated with acute work-related injuries, and everyday associated with acute, nonspecific after administration of the IR and painful musculoskeletal conditions, activities, which account for acute musculoskeletal conditions. -

Drug Class Review on Skeletal Muscle Relaxants

Drug Class Review on Skeletal Muscle Relaxants Final Report Update 2 May 2005 Original Report Date: April 2003 Update 1 Report Date: January 2004 A literature scan of this topic is done periodically The purpose of this report is to make available information regarding the comparative effectiveness and safety profiles of different drugs within pharmaceutical classes. Reports are not usage guidelines, nor should they be read as an endorsement of, or recommendation for, any particular drug, use or approach. Oregon Health & Science University does not recommend or endorse any guideline or recommendation developed by users of these reports. Roger Chou, MD Kim Peterson, MS Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center Oregon Health & Science University Mark Helfand, MD, MPH, Director Copyright © 2005 by Oregon Health & Science University Portland, Oregon 97201. All rights reserved. Note: A scan of the medical literature relating to the topic is done periodically (see http://www.ohsu.edu/ohsuedu/research/policycenter/DERP/about/methods.cfm for scanning process description). Upon review of the last scan, the Drug Effectiveness Review Project governance group elected not to proceed with another full update of this report. Some portions of the report may not be up to date. Prior versions of this report can be accessed at the DERP website. Final Report Update 2 Drug Effectiveness Review Project TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................................4 Scope and -

CYCLOBENZAPRINE (Brand Name: Flexeril®, Amrix®)

Drug Enforcement Administration Diversion Control Division Drug & Chemical Evaluation Section CYCLOBENZAPRINE ® ® (Brand Name: Flexeril , Amrix ) March 2020 Introduction: Illicit Uses: Cyclobenzaprine is a central nervous system Anecdotal reports found on the Internet suggest (CNS) muscle relaxant intended for short-term use that individuals are taking cyclobenzaprine alone or in the treatment of pain, tenderness and limitation of in combination with other illicit drugs to produce or motion caused by muscle spasms. Cyclobenzaprine enhance psychoactive effects. Individuals have may enhance the effects of other CNS depressants reported taking cyclobenzadrine both orally and including alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines intra-nasally at doses ranging from 10 mg to 60 mg. and narcotics and anecdotal reports indicate it is Sedation, relaxation and increased heart rate were used non-medically to induce euphoria and the most common effects reported. Euphoria was relaxation. reported by a smaller number of individuals. Licit Uses: Illicit Distribution: Cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride is approved for Several indicators suggest that cyclobenzaprine use in the United States as a muscle relaxant. It is is being intentionally misused or abused. According marketed under the brand names Flexeril® and to the American Association of Poison Control Amrix® and as generic formulations in 5, 7.5, and 10 Centers, 10,615 case mentions and 4,444 single mg tablets intended for short-term (2 to 3 week) oral exposures were associated with cyclobenzaprine in administration. The usual starting dose is 5 mg, 2016, resulting in 75 major medical outcomes and three times per day. The maximum recommended four deaths among single substance exposures. In dose is 10 mg, three times daily. -

Active Moiety Name FDA Established Pharmacologic Class (EPC) Text

FDA Established Pharmacologic Class (EPC) Text Phrase PLR regulations require that the following statement is included in the Highlights Indications and Usage heading if a drug is a member of an EPC [see 21 CFR 201.57(a)(6)]: “(Drug) is a (FDA EPC Text Phrase) indicated for [indication(s)].” For Active Moiety Name each listed active moiety, the associated FDA EPC text phrase is included in this document. For more information about how FDA determines the EPC Text Phrase, see the 2009 "Determining EPC for Use in the Highlights" guidance and 2013 "Determining EPC for Use in the Highlights" MAPP 7400.13. .alpha. -

Anaesthetic Implications of Calcium Channel Blockers

436 Anaesthetic implications of calcium channel Leonard C. Jenkins aA MD CM FRCPC blockers Peter J. Scoates a sc MD FRCPC CONTENTS The object of this review is to emphasize the anaesthetic implications of calcium channel block- Physiology - calcium/calcium channel blockers Uses of calcium channel blockers ers for the practising anaesthetist. These drugs have Traditional played an expanding role in therapeutics since their Angina pectoris introduction and thus anaesthetists can expect to see Arrhythmias increasing numbers of patients presenting for anaes- Hypertension thesia who are being treated with calcium channel Newer and investigational Cardiac blockers. Other reviews have emphasized the basic - Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pharmacology of calcium channel blockers. 1-7 - Cold cardioplegia - Pulmonary hypertension Physiology - calcium/calcium channel blockers Actions on platelets Calcium plays an important role in many physio- Asthma Obstetrics logical processes, such as blood coagulation, en- - Premature labor zyme systems, muscle contraction, bone metabo- - Pre-eclampsia lism, synaptic transmission, and cell membrane Achalasia and oesophageal spasm excitability. Especially important is the role of Increased intraocular pressure therapy calcium in myocardial contractility and conduction Protective effect on kidney after radiocontrast Cerebral vasospasm as well as in vascular smooth muscle reactivity. 7 Induced hypotensive anaesthesia Thus, it can be anticipated that any drug interfering Drag interactions with calcium channel blockers with the action of calcium could have widespread With anaesthetic agents effects. Inhalation agents In order to understand the importance of calcium - Effect on haemodynamics - Effect on MAC in cellular excitation, it is necessary to review some Neuromuscular blockers membrane physiology. Cell membranes are pri- Effects on epinephrine-induced arrhythmias marily phospholipids arranged in a bilayer. -

Paracetamol/Chlorzoxazone

PARACETAMOL/CHLORZOXAZONE TRADE NAME MYOLGIN™ NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Paracetamol / chlorzoxazone, 300 mg/250 mg, hard capsule QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each hard capsule contains 300 mg of paracetamol and 250 mg of chlorzoxazone. Excipients Gelatin, Magnesium stearate, Talc. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Hard gelatin capsules, purple opaque/pink printed Myolgin. CLINICAL INFORMATION Indications Paracetamol/chlorzoxazone is indicated for the treatment of: • sprains, strains, muscle pain, • traumatic muscle spasm, • reflex muscle spasm associated with rheumatic diseases, • lumbago, • myalgia, • tension headache, • torticollis, • cervical root syndrome, • rheumatoid arthritis. This medicinal product offers quick relief of pain and restore mobility even in severely painful spasms of the skeletal muscles in cases as above. Dosage and Administration Route of Administration For oral use. Adults Unless otherwise prescribed by a physician, the dose is 1 to 2 capsules three times daily after meals according to the severity of symptoms. Daily dose should not exceed 4 grams of paracetamol and 3 grams of chlorzoxazone. Do not exceed the stated dose. Minimum dosing interval: 4 hours Children This medicinal product is not recommended for children under 12 years. Elderly There are no relevant data available. Renal impairment Patients who have been diagnosed with renal impairment must seek medical advice before taking this medication (see Section Warnings and Precautions) Page 1 of 8 Hepatic impairment This medicinal product should not be given to patients with impaired liver function (see Section Warnings and Precautions). Contraindications Paracetamol / chlorzoxazone is contraindicated in: • hypersensitivity to the active substances or any of the excipients. Warnings and Precautions Renal impairment Care is advised in the administration of paracetamol/ chlorzoxazone to patients with renal impairment. -

A Review of the Evidence of Use and Harms of Novel Benzodiazepines

ACMD Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs Novel Benzodiazepines A review of the evidence of use and harms of Novel Benzodiazepines April 2020 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Legal control of benzodiazepines .......................................................................................... 4 3. Benzodiazepine chemistry and pharmacology .................................................................. 6 4. Benzodiazepine misuse............................................................................................................ 7 Benzodiazepine use with opioids ................................................................................................... 9 Social harms of benzodiazepine use .......................................................................................... 10 Suicide ............................................................................................................................................. 11 5. Prevalence and harm summaries of Novel Benzodiazepines ...................................... 11 1. Flualprazolam ......................................................................................................................... 11 2. Norfludiazepam ....................................................................................................................... 13 3. Flunitrazolam .......................................................................................................................... -

Skeletal Muscle Relaxants Review 05/31/2010

Skeletal Muscle Relaxants Review 05/31/2010 Copyright © 2007 – 2010 by Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage and retrieval system without the express written consent of Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Attention: Copyright Administrator Intellectual Property Department Provider Synergies, L.L.C 10101 Alliance Road, Suite 201 Cincinnati, Ohio 45242 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended -

Comparative Study of Muscle Relaxant Activity of Alprazolam with Diazepam in Mice

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 17, Issue 9 Ver. 5 (September. 2018), PP 09-14 www.iosrjournals.org Comparative Study of Muscle Relaxant Activity of Alprazolam With Diazepam In Mice Syed Shadman Ahmad1*, Supriya Priyambadha2 1*Assistant Professor, Dept. of Pharmacology,Rama medical college Hospital and Research center,Kanpur 2 Professor, Department of Pharmacology, Dr.Pinnamaneni Siddhartha Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Foundation, Chinaoutpalli, Krishna (Dist), Andhra Pradesh Corresponding author: Syed Shadman Ahmad Abstract: Background: A muscle relaxant is a drug which affects skeletal muscle function and decreases the muscle tone. It may be used to alleviate symptoms such as muscle spasm, pain and hyperreflexia. Skeletal muscle relaxants are heterogeneous group of medications that refer to 2 major therapeutic groups: neuromuscular blockers and spasmolytics. Aim and objectives: The study was designed to assess the muscle relaxant activity of alprazolam and compare the muscle relaxant activity of alprazolam with diazepam using albino male mouse as experimental model Materials and methods: The white albino mice were selected, weighed and numbered. A total of 24 animals weighing about 30 grams were selected for the present study. They were divided into four groups each group consists of 6 mice. The animal was placed one by one on the rotarod more than one mouse at a time were placed. Initially free fall off reading was taken before administration of drugs. The free fall off time was noted when the mouse falls from the rotating rod. A normal untreated mouse generally falls off within 3-5 minutes. -

Sonata®(Zaleplon) Capsules CIV

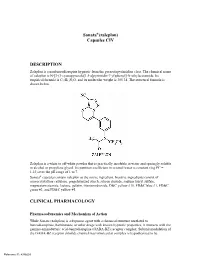

Sonata®(zaleplon) Capsules CIV DESCRIPTION Zaleplon is a nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic from the pyrazolopyrimidine class. The chemical name of zaleplon is N-[3-(3-cyanopyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-7-yl)phenyl]-N-ethylacetamide. Its empirical formula is C17H15N5O, and its molecular weight is 305.34. The structural formula is shown below. Zaleplon is a white to off-white powder that is practically insoluble in water and sparingly soluble in alcohol or propylene glycol. Its partition coefficient in octanol/water is constant (log PC = 1.23) over the pH range of 1 to 7. Sonata® capsules contain zaleplon as the active ingredient. Inactive ingredients consist of microcrystalline cellulose, pregelatinized starch, silicon dioxide, sodium lauryl sulfate, magnesium stearate, lactose, gelatin, titanium dioxide, D&C yellow #10, FD&C blue #1, FD&C green #3, and FD&C yellow #5. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Pharmacodynamics and Mechanism of Action While Sonata (zaleplon) is a hypnotic agent with a chemical structure unrelated to benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or other drugs with known hypnotic properties, it interacts with the gamma-aminobutyric acid-benzodiazepine (GABA-BZ) receptor complex. Subunit modulation of the GABA-BZ receptor chloride channel macromolecular complex is hypothesized to be Reference ID: 4386603 responsible for some of the pharmacological properties of benzodiazepines, which include sedative, anxiolytic, muscle relaxant, and anticonvulsive effects in animal models. Other nonclinical studies have also shown that zaleplon binds selectively to the brain omega-1 receptor situated on the alpha subunit of the GABAA/chloride ion channel receptor complex and potentiates t-butyl-bicyclophosphorothionate (TBPS) binding. Studies of binding of zaleplon to recombinant GABAA receptors (α1β1γ2 [omega-1] and α2β1γ2 [omega-2]) have shown that zaleplon has a low affinity for these receptors, with preferential binding to the omega-1 receptor. -

FDA Listing of Established Pharmacologic Class Text Phrases January 2021

FDA Listing of Established Pharmacologic Class Text Phrases January 2021 FDA EPC Text Phrase PLR regulations require that the following statement is included in the Highlights Indications and Usage heading if a drug is a member of an EPC [see 21 CFR 201.57(a)(6)]: “(Drug) is a (FDA EPC Text Phrase) indicated for Active Moiety Name [indication(s)].” For each listed active moiety, the associated FDA EPC text phrase is included in this document. For more information about how FDA determines the EPC Text Phrase, see the 2009 "Determining EPC for Use in the Highlights" guidance and 2013 "Determining EPC for Use in the Highlights" MAPP 7400.13. -

Benzodiazepines: What You Need to Know About Sleeping Pills

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT SLEEPING PILLS WHAT ARE BENZODIAZEPINES? Benzodiazepines are commonly prescribed medications, accounting for around one in every 20 prescriptions written by GPs in Australia.1 Benzodiazepines are quite often prescribed in a tablet or capsule form that is not intended for injection. Benzodiazepines are also known as ‘benzos’ and are also a type of sedative. They may also be referred to as sleeping tablets or sleeping pills. Benzodiazepines are prescribed for a range of problems, including anxiety and insomnia. They have anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing), sedative and muscle relaxant effects. They can also reduce or stop convulsions. They can be addictive, so are usually prescribed for short-term problems; only for a few weeks usage or for very occasional use. The most well-known is diazepam or Valium.1, 2 Examples of benzodiazepines: Generic Name Brand Names diazepam Valium, Antenex, Ducene, Valpam alprazolam Xanax, Kalma, Alprax clonazepam Rivotril, Paxam nitrazepam Mogadon oxazepam Serepax temazepam Normison, Euhypnos, Temaze WHAT IS STILNOX? Another drug sometimes prescribed for sleep problems is Stilnox (zolpidem). It isn’t strictly a benzodiazepine, but it has similar characteristics. It has received a lot of media attention in recent years due to people having accidents while sleepwalking under the influence. It is also considered to be habit-forming (addictive) and regular use is not recommended.2 WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS? Benzodiazepines are depressant drugs, meaning that they slow down the central nervous system, or reduce the function of the brain and body. They can cause feelings of relaxation and mild contentment, or even sedation and total blackout.