Roseau River Watershed Resource Inventory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload Updated December 17, 2019 Serviced Out Of City Prov Routing City Carrier Name ADAM LAKE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ALEXANDER MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ALONSA MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ALTAMONT MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ALTONA MB WINNIPEG, MB Direct Service Point AMARANTH MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ANGUSVILLE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ANOLA MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARBORG MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARDEN MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARGYLE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARNAUD MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARNES MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ARROW RIVER MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ASHERN MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point ATIKAMEG LAKE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point AUBIGNY MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point AUSTIN MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BADEN MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BADGER MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BAGOT MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BAKERS NARROWS MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BALDUR MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BALMORAL MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BARROWS MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BASSWOOD MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BEACONIA MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BEAUSEJOUR MB WINNIPEG, MB Direct Service Point BELAIR MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BELMONT MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BENITO MB YORKTON, SK Interline Point BERESFORD MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BERESFORD LAKE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BERNIC LAKE MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BETHANY MB WINNIPEG, MB Interline Point BETULA MB WINNIPEG, -

2020 Winners

2020 U MANITOBA! NK YO THA PRESENTED BY FOR YOUR SUPPORT OF THE $664,590 2008558 Miller, Mark - Winnipeg 2282667 Shindela, Leslie - Brandon $6,500 CWT Vacations Travel Voucher or a Winnipeg SUMMER BONUS 20 WINNERS Jets Suite to a 2020-2021 Home game for 12 people 2020 Honda HR-V (valued at $29,104) or a 2020 Toyota C-HR LE OF $1,000 CASH (valued at $6,000) plus $500 Cash or $5,000 Cash (valued at $25,982.20) or $25,000 Cash 2057738 Anaka, Jason - Winnipeg 2038608 Wright, Barb - Winnipeg 2055602 Marleau, Darrell - Winnipeg 2058509 Bergen, Joseph - Winnipeg 2020 Yamaha EXR Waverunner with PWC Karavan 2027226 Cheater, Ardis - Winnipeg Trailer (valued at $16,799) or a $15,000 CWT DREAM BONUS 2028387 Dujlovic, Toni - Winnipeg Vacations Travel Voucher or $12,000 Cash 2046505 Ferguson, Oswald - Winnipeg 2001125 Harrison, Jamie - Winnipeg Mercedes-Benx 2020 GLC300 4MATIC SUV (valued at 2038080 Fresnoza, Agnes - Winnipeg $64,233.75) or a 2020 Toyota Tacoma 4x4 Access Cab 6A (valued 2021611 Gilson, Susan - Deloraine 2020 Harley-Davidson FLHXS Street Glide (valued at at $42,306.18) plus a 2020 Jayco Jayflight 195RB Travel Trailer 2011579 Godbout, Kirsten - Winnipeg $33,799) or a $28,000 CWT Vacations Travel Voucher (valued at $25,122) or $55,000 Cash 2055629 Gottfried, Michael - Ile Des Chenes plus $2,000 Cash or $25,000 Cash 2025321 Friesen, Edith - Altona 2050837 Hargest, John - Winnipeg 2051673 Birur, Anand - Winnipeg 2002916 King, Elizabeth - Whitemouth 2020 Honda Passport Sport (valued at $44,974) EARLY BIRD 2019742 Maddocks, Rose - Winnipeg -

Manitoba – Minnesota Transmission Project Environmental Impact

9 7 4 11 6 Stonewall 67 Selkirk Manitoba-Minnesota Lower 8 Cooks Creek/ Beausejour Assiniboine River Devils59 Creek Transmission Project Sub-Watershed Dorsey Sub-Watershed 05MJ Project Infrastructure 26 101 05OJ Converter Station (Existing) 44 1 15 Final Preferred Route (FPR) Riel City of Winnipeg C boine River o Infrastructure Assini ok 05OG s C reek Existing 500kV Transmission Line La Salle River 100 Existing 230kV Transmission Line 13 Sub-Watershed 2 Aquatics Survey Sites M a Survey Site n n Ste. Anne i n S g e 1 i 1 n C e Sub-Watersheds a R n a iv 05OJ e Cooks Creek/Devils Creek Sub-Watershed l r Ontatrio Manitoba La Salle River Sub-Watershed Niverville M602F Lower Assiniboine River Sub-Watershed 3 Seine River Sub-Watershed Rat River Sub-Watershed 75 Steinbach Red River Sub-Watershed 59 Roseau River Sub-Watershed 12 05OH r e iv Seine River Sub-Watershed R J St-Pierre-Jolys o u d b e e Landbase R rt C re e Community Morris k Rat River 1 Trans Canada Highway Sub-Watershed 05OE 12 Provincial Highway WHITEMOUTH City / Town Red River Rat River LAKE First Nation Lands Provincial Park Sub-Watershed River u a e 14 s o Winkler R LAKE OF THE 05OC Roseau River WOODS Piney 32 Sub-Watershed 05OD 30 89 Emerson Canada Gretna United States of America Source: 1. Sub-Basins, 2013, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Coordinate System: UTM Zone 14N NAD83 Data Source: MBHydro, ProvMB, NRCAN Date Created: July 21, 2015 0 10 Kilometres MINNESOTA NORTH 0 5 10 Miles 1:750,000 DAKOTA Sub-Watersheds Map 8-1 G:\_GIS_Project_Folder\00_Hydro\111420050_MMTP_EA\Figures\EAChapter\AquaticEnvironment\MMTP_EA_AquaWatersheds_750K_B_20150713.mxd Selkirk Stonewall 67 11 Stony Seddons Mountain Corner 44 Grosse Isle Beausejour Whiteshell 59 Provincial 27 Molson Park Birds Hill Provincial Manitoba-Minnesota Park Cloverleaf Dorsey Transmission Project Rosser 101 Whitemouth 26 Hazelridge Project Infrastructure Oakbank 12 Converter Station (Existing) 44 Vivian Elma Final Preferred Route (FPR) Dugald Glass Anola 15 1 Ste. -

Carte Des Zones Contrôlées Controlled Area

280 RY LAKE 391 MYSTE Nelson House Pukatawagan THOMPSON 6 375 Sherridon Oxford House Northern Manitoba ds River 394 Nord du GMo anitoba 393 Snow Lake Wabowden 392 6 0 25 50 75 100 395 398 FLIN FLON Kilometres/kilomètres Lynn Lake 291 397 Herb Lake 391 Gods Lake 373 South Indian Lake 396 392 10 Bakers Narrows Fox Mine Herb Lake Landing 493 Sherritt Junction 39 Cross Lake 290 39 6 Cranberry Portage Leaf Rapids 280 Gillam 596 374 39 Jenpeg 10 Wekusko Split Lake Simonhouse 280 391 Red Sucker Lake Cormorant Nelson House THOMPSON Wanless 287 6 6 373 Root Lake ST ST 10 WOODLANDS CKWOOD RO ANDREWS CLEMENTS Rossville 322 287 Waasagomach Ladywood 4 Norway House 9 Winnipeg and Area 508 n Hill Argyle 323 8 Garde 323 320 Island Lake WinnBRiOpKEeNHEgAD et ses environs St. Theresa Point 435 SELKIRK 0 5 10 15 20 East Selkirk 283 289 THE PAS 67 212 l Stonewall Kilometres/Kilomètres Cromwel Warren 9A 384 283 509 KELSEY 10 67 204 322 Moose Lake 230 Warren Landing 7 Freshford Tyndall 236 282 6 44 Stony Mountain 410 Lockport Garson ur 220 Beausejo 321 Westray Grosse Isle 321 9 WEST ST ROSSER PAUL 321 27 238 206 6 202 212 8 59 Hazelglen Cedar 204 EAST ST Cooks Creek PAUL 221 409 220 Lac SPRINGFIELD Rosser Birds Hill 213 Hazelridge 221 Winnipeg ST FRANÇOIS 101 XAVIER Oakbank Lake 334 101 60 10 190 Grand Rapids Big Black River 27 HEADINGLEY 207 St. François Xavier Overflowing River CARTIER 425 Dugald Eas 15 Vivian terville Anola 1 Dacotah WINNIPEG Headingley 206 327 241 12 Lake 6 Winnipegosis 427 Red Deer L ake 60 100 Denbeigh Point 334 Ostenfeld 424 Westgate 1 Barrows Powell Na Springstein 100 tional Mills E 3 TACH ONALD Baden MACD 77 MOUNTAIN 483 300 Oak Bluff Pelican Ra Lake pids Grande 2 Pointe 10 207 eviève Mafeking 6 Ste-Gen Lac Winnipeg 334 Lorette 200 59 Dufresne Winnipegosis 405 Bellsite Ile des Chênes 207 3 RITCHOT 330 STE ANNE 247 75 1 La Salle 206 12 Novra St. -

8.5" X 11" - 90% - 11" X 8.5" Ross

Little Haider Goose Lake Putahow Nueltin Head River Ballantyne L Falloon Egg Lopuck Lake Commonwealth L Partridge Lake Todd Lake Nabel Is Lake Lake Strachan Putahow Blevins Coutts Veal L Lake Lake Lake Tice Lake Savage Lake Hutton Lake Lake Lake Dickins R Nahili Bulloch Colvin L John Lake R Lake Koona Osborn Round Gronbeck Thuytowayasay L Jonasson Gillander Lake Bangle Inverarity Sand L Lake L Kasmere Lake Lake Lake Lake McEwen Sucker Drake Ewing Kitchen CARIBOU RIVER Lake Sandy L Guick Ashey Lake Kirk L Lake L Lake Shannon Lake Gagnon Vinsky Secter L Hanna L River Turner Corbett Lake Nejanilini Lake Butterworth Lake Lemmerick Creba Lake Croll PARK RESERVE Ck Lake Lake L Lake Kasmere Lake Falls Tatowaycho R Creek L Grevstad Thlewiaza Caribou HUDSON Bartko MacMillian Lake Hillhouse Booth Little Long Snyder L Lake Bambridge Lake Lake Duck Jethe Lake Lake L Baird Lake L Ibbott Alyward Lake Duck Lake Post River Lake Choquette L Caribou Gross Hubbart Point Lake Sandhill Wolverine Lake L Fort Hall Lake Topp L Maughan Clarke River Ouellet Lake L L Ferris Atemkameskak Big Van Der Vennet Mistahi Lake Palulak L L Brownstone Barr Quasso L L Colbeck Doig Munroe Oolduywas Lake Lake Lake L Blackfish Lake Lake Lake Spruce Lake Sothe Sothe Macleod L Endert Cangield L Whitmore Minuhik R Law Lake L Lake Cochrane R Lake Lake Warner Lake Adair Naelin Thuykay Tessassage Greening L Lake L Lake Weepaskow North Lake Duffin Egenolf Lake Hoguycho Numaykos L Copeland Spruce Point of the Woods Lake L River L Blenkhorn Apeecheekamow L Lake Misty Mcgill Chatwin Seal -

Themanitoba Manitoba

THEManitoba azette Gazette GDU Manitoba Vol. 146 No. 40 October 7, 2017 ● Winnipeg ● le 7 octobre 2017 Vol. 146 no 40 Table of Contents Estate: Schwartz, Shirley J ............................................. 374 GOVERNMENT NOTICES Estate: Stiefmaier, Mathilda ........................................... 374 Estate: Toyne, Bruce R ................................................... 374 Under The Cooperatives Act: Estate: Truchan, Maria ................................................... 374 Erratum .......................................................................... 369 Estate: Vnuk, John P ...................................................... 375 Estate: Wright, Margaret G ............................................ 375 Under The Highway Traffic Act: Estate: Zack, William B ................................................. 375 Operating Authority ....................................................... 370 Under The Executions Act: Court Notice Under Application To The Legislature / Demande À Législature: Canada Revenue Agency vs. Don McDonald................. 375 Application for Private Bills / Demande de présentation d’un projet de loi privée ...... 371 Under The Garage Keepers Act: Auction ........................................................................... 375 Auction ........................................................................... 375 PUBLIC NOTICES Under The Trustee Act: Estate: Baron, Archibald ................................................ 373 Estate: Brounstein, Sheldon B ...................................... -

Central Metal Recovery Inc., Waste Acid Batteries Transfer Facility, Zhoda, RM of La Broquerie, Licence

Central Metal Recovery Inc., Waste Acid Batteries Transfer Facility, Zhoda, RM of La Broquerie, Licence Licence No.: 136 HW Licence Issued: November 28, 2001 In accordance with the Manitoba Dangerous Goods Handling and Transportation Act (C.C.S.M. c. D12) THIS LICENCE IS ISSUED TO: CENTRAL METAL RECOVERY INC.; "the Licencee" for the construction and operation of a Waste Lead Acid Battery transfer facility (the facility) located at SE¼ 12-4-7 EPM, near Zhoda in the Rural Municipality of La Broquerie, Manitoba, in accordance with the Application dated December 27, 2000 and the additional information received March 19, 2001 and July 24, 2001 filed under The Dangerous Goods Handling and Transportation Act, and subject to the following specifications, limits, terms and conditions: DEFINITIONS In this Licence, "accredited laboratory" means facilities accredited by the Standard Council of Canada (SCC), or facilities accredited by another accrediting agency recognized by Manitoba Conservation to be equivalent to the SCC, or facilities which can demonstrate to Manitoba Conservation, upon request, that quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC) procedures are in place equivalent to accreditation based on the Canadian Standard Can/CSA-Z753, extension of the international standard ISO 9000, Guide 25; "Director" means an employee of the department who has been designated or appointed by the Minister; "permanently closed" means that the facility has not been operated for a period of 6 months or more; "waste battery" means a lead-acid electromotive battery that: a. through use, storage, handling, defect, damage, expiry of shelf life or other similar circumstance can no longer be used for its original purpose; or b. -

Rural Municipality of Stuartburn

Rural Municipality of Stuartburn Minutes of the regular council meeting of Tuesday February 17TH, 2015 at 7:00pm in the Municipal Council Chambers, Vita, Manitoba Present: Reeve Jim Swidersky Deputy Reeve: Ed Penner Councillors: Dan Bodz, Jerry Lubiansky and Konrad Narth Chief Administrative Officer Lucie Maynard, CMMA Reeve Swidersky called the meeting to order at 7:06 P.M. 38-15 Moved by Ed Penner Seconded by Dan Bodz WHEREAS the minutes of the Regular Meeting of February 3rd, 2015 are correctly recorded as presented, BE IT RESOLVED THAT the minutes of the February 3rd, 2015 meeting be adopted as circulated. Carried Delegation: Dale Fisher Came before council to question why he was denied to purchase the S ½ NW 32-1-7E. Mr. Fisher makes a new offer. Council will consider. Darryl Kantimer Came before council to request a pre-approval to adding an additional lot. Council explained the subdivision process to Mr. Kantimer. Mr. Kantimer stated he reviewed council’s statements of assets and interest and feels they are not correctly filled out for some members. Council takes note. Mr. Kantimer also has concerns with Mr. Pat Smith’s proposed sheep operation in the zhoda area. Council reiterates that no proposal has been brought to council’s attention. Council cannot prohibit anyone from buying land and currently that is all Mr. Smith is doing. Dave Kiansky Came before council to request that council apply for a standing drainage license to dig out the Old Roseau River. Council has been in contact with MIT to discuss jurisdiction to maintain the Old Roseau River since it was the Province who looked after this area in the past. -

2018 Population Report

1 Population Statistics 2018 | Southern Health-Santé Sud Published: April 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Background 3 3 Municipal Amalgamations for 2018 4 2018 Population – Southern Health-Santé Sud Zone 1 (former North Area) 5 Zone 2 (former Mid Area) 6 Zone 3 (former West Area) 7 Zone 4 (former East Area) 8 9 10 Year Population Growth (2008-2018) Manitoba RHA Comparisons 9 11 Age Group Comparisons 12 District and Municipal Population Change 15 Indigenous Population 16 Map of Region This publication is available in alternate format upon request. 2 Population Statistics 2018| Southern Health-Santé Sud ABOUT THIS REPORT The population data shown in this report is based on records of residents actively registered with Manitoba Health as of June 1, 2018 and published by Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living (http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/population/). This population database is considered a reliable and accurate estimate of population sizes, and is helpful for understanding trends and useful for health planning purposes. The Indigenous population has also been updated in March 2019 by the Indigenous Health program with the great help of Band Membership clerks. Please note that in 2018, international students, their spouses, and dependents were excluded because they were no longer eligible for provincial health insurance. This has impacted the population counts by approximately 10,000, largely from WRHA, compared to previous reports. Municipal Amalgamations A series of municipal amalgamations came into effect as of January 1, 2015. A map of Southern -

Fast-Dueck Harold and Nettie (Dueck) Fast Thank and Praise the Lord for Giving Them 65 Wonderful Years Together

MAY 8. 2014 THE CARILLON WEDDING ANNIVERSARY ALBUM PAGE 1 65th Fast-Dueck Harold and Nettie (Dueck) Fast thank and praise the Lord for giving them 65 wonderful years together. They were married at the Kleefeld E.M. Church on June 12, 1949 with Rev John R. Friesen offi ciating. They were blessed with six wonderful children, 15 grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren. Nettie worked as a homemaker while Harold worked for the municipality of Hanover for 45 years. They are now enjoying their retirement years gardening, bird watching and spending time with family 2014 and friends. Supplement to The Carillon May 8, 2014 PAGE 2 THE CARILLON WEDDING ANNIVERSARY ALBUM MAY 8. 2014 th 60 Kehler-Peters William (Bill) Kehler and Katharina (Tina) Peters were mar- ried on Oct. 17, 1954. They operated a family dairy farm on Ekron-Oswald Road in La Broquerie until retirement in 1990. They built a house in Steinbach and continued to garden and en- th joy freedom to travel. They recently sold their home and reside at th Fernwood. They have been blessed with a family of seven chil- 60 dren, 15 grandchildren and six great-grandchildren with one on 60 Hildebrandt-Friesen the way. They are thankful for God’s abundant blessings. Dueck-Derksen Jake D. Hildebrandt and Susan Friesen were married in Stu- Frank and Sara (nee Derksen) Dueck were married on June 20, artburn, MB on Oct. 12, 1954. Jake, a retired teacher, and Susan, 1954 – 60 years married. They have three children, five grand- a retired nurses’ aid, were both born in Stuartburn. -

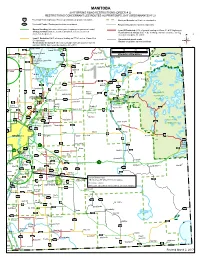

Road-Restrictions-Map-2017.Pdf

MANITOBA 2017 SPRING ROAD RESTRICTIONS (ORDER # 2) RESTRICTIONS CONCERNANT LES ROUTES AU PRINTEMPS 2017 (ORDONNANCE Nº 2) 75 Provincial Trunk Highways / Routes provinciales à grande circulation 200 Provincial Roads / Routes provinciales secondaires MunicipalRM Boundaries / Limites municipales RegionalRegion Boundaries / Limites régionales NormalNormal Loading Loading (all surfaced/non gravel highways or provincial roads) Charge normale (toutes les routes provinciales revêtues ou non couvertes de gravier) LevelLevel 2 Restricted 2 Restriction (65% of normal loading on Class A1 & B1 highways) Restrictions de niveau 2 (65 % de la charge normale autorisée sur les routes de catégorie A1 et B1) LevelLevel 1 Restricted 1 Restriction (90% of normal loading on RTAC routes, Class A1 & B1 highways) Unrestricted gravel roads Restrictions de niveau 1 (90 % de la charge normale autorisée sur les Unrestricted parcours ARTC des routes de catégorie A1 et B1) Routes en gravier sans restrictions Sandy Hook Grand Beach 519 eorges Grand Marais 12 St-G PROV. PARK 229 Winnipeg Beach 0102030 Silver Falls Komarno ST. 500 ANDREWS 232 kilometers/kilomètres Ponemah 315 Whytewold ttar 304 Great Falls 225 Dunno White Mud Falls Matlock Beaconia Stead 319 304 17 LAC McArthur Falls Teulon Thalberg DU BONNET Netley ST. 315 CLEMENTS 12 313 433 Petersfield 1317 313 Pointe du Libau 320 Bois 317 Lac du 502 Bonnet Clandeboye Brokenhead 7 59 520 8 9 BROKENHEAD Milner 4 Ladywood Ridge 214 LGD 11 PINAWA WHITESHELL SELKIRK 508 Pinawa 435 307 PROVINCIAL 67 East Selkirk 211 9A Cromwell PARK Stony Tyndall- Seven Sisters Falls Mountain 230 Garson Seddons WHITEMOUTH 21 220 Lockport 44 Beausejour Corner River Hills W. -

Terrifying Home Invasion Haunts Zhoda-Area Couple

Mitchell wins Humane fastball title society looks forward to TERRY FREY 1C growth. JENNIFER STAHN 2A INDEX: 9C Agriculture 6C Church news 1B Classified 10C Family newsVolume10A 6 3Obituaries Number1C 1 Sports $1.11 PAP Registration No. 09043 VOLUME 63 Agreement No. 0040010296 Steinbach, Manitoba, Thursday, September 11, 2008 42 Pages NUMBER 37 St Labre man, 29 witnesses horror on Greyhound bus by Jennifer Stahn pulled over, grabbed a pipe from his truck and ran to the bus. He HRISTOPHER Alguire said the scene was quite chaotic has the physical presence, but noted he immediately tried to Cand the temper, to scare off take charge of the situation. many people, but it was his heart He moved everyone about 30 and compassion that stood out feet behind the cargo area of the most on the night of July 29 when bus, where they could not see Tim McLean was horrifically mur- what was happening on board dered in front of 37 other passen- and his friend Evelyn (who was gers on a Greyhound bus travelling travelling with him) could talk to from Edmonton to Winnipeg. the passengers in an effort to calm The incident drew international them down. media attention and led the news Working mostly on adrenaline for several days. and with the help of a passenger Alguire, who just turned 29 last (Garnet), Alguire coordinated a week, was guiding his highway small group to help him watch DORIS PENNER • THE CARILLON tractor along the Trans-Canada the sides of the bus to make sure Assisting Steinbach mayor Chris Goertzen with ribbon-cutting at the MCC Thrift Store grand opening are Helen Klassen, Tina Kehler, Sarah Dueck, Anne Bilsky, Eva Wiebe and Christine Putz.