I CONCEPTUAL PLURALISM in the UNDERSTANDING of POVERTY: a CASE STUDY of NIGERIA. by LOUIS NWABUEZE EZEILO SUBMITTED in ACCORDANC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

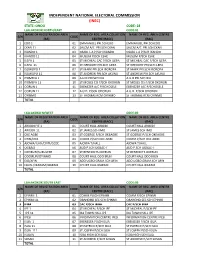

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: an Historical Analysis, 1804-1960

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: An Historical Analysis, 1804-1960 by Kari Bergstrom Michigan State University Winner of the Rita S. Gallin Award for the Best Graduate Student Paper in Women and International Development Working Paper #276 October 2002 Abstract This paper looks at the effects of Islamization and colonialism on women in Hausaland. Beginning with the jihad and subsequent Islamic government of ‘dan Fodio, I examine the changes impacting Hausa women in and outside of the Caliphate he established. Women inside of the Caliphate were increasingly pushed out of public life and relegated to the domestic space. Islamic law was widely established, and large-scale slave production became key to the economy of the Caliphate. In contrast, Hausa women outside of the Caliphate were better able to maintain historical positions of authority in political and religious realms. As the French and British colonized Hausaland, the partition they made corresponded roughly with those Hausas inside and outside of the Caliphate. The British colonized the Caliphate through a system of indirect rule, which reinforced many of the Caliphate’s ways of governance. The British did, however, abolish slavery and impose a new legal system, both of which had significant effects on Hausa women in Nigeria. The French colonized the northern Hausa kingdoms, which had resisted the Caliphate’s rule. Through patriarchal French colonial policies, Hausa women in Niger found they could no longer exercise the political and religious authority that they historically had held. The literature on Hausa women in Niger is considerably less well developed than it is for Hausa women in Nigeria. -

Report on Campaign Against Electoral Violence – 2007 Plateau State

Report on Campaign against Electoral Violence – 2007 Plateau State With the collaboration of YARAC - Youth, Adolescent, Reflection and Action Center YARAC Creativity & Service REPORT ON ACTIVITIES DURING THE CAMPAIGNS REPORT ON THE CAMPAIGN AGAINST ELECTORAL VIOLENCE IN NIGERIA INTRODUCTION As a prelude to the Campaign against Electoral Violence in Nigeria, a survey was conducted with the aid of the annual Afro-Barometer/PSI surveys. The specific targets though in relation to the CAEVIN Project in Plateau state included two local government areas in just six(6) states. The whole essence of the survey was to determine change in perceptions before and after sensitization through campaigns in these states which have been noted to have a propensity towards conflict and other negatives during periods of election. Surveys in Plateau state were conducted in two local government areas. Jos-n North and Qua’an Pan. In Jos-North there were two designated enumeration areas, and these were; Those for Jos-north were; - Unity Commercial Institute - Alhaji Sabitu Abass Those for Qua’an Pan were; - Agwan Dan Zaria in Piya (or Ampiya) - Mai Anglican, Pandam From the surveys taken, one clearly noticeable drawback was the fact that the names of designated enumeration areas had been extracted from an obsolete source, thereby creating a drawback in locating these places. All of the designated places have had their names replaced, and it was later discovered that the names were extracted from a 1970’s census document. Places like Unity Commercial and Angwan Dan Zaria for instance had lost their names due to the either the change in the name of the landmark, as was seen with Unity Commercial, which was the name of a school, and is now called Highland College. -

Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Ab

African Scholar VOL. 18 NO. 6 Publications & ISSN: 2110-2086 Research SEPTEMBER, 2020 International African Scholar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (JHSS-6) Study of Forms and Functions of Esu – Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Fine and Applied Arts Department, School of Vocational and Technical Education, Tai Solarin College of Education, Omu – Ijebu Abstract The representational images such as pots, rattles, bracelets, stones, cutlasses, wooden combs, staffs, mortals, brooms, etc. are religious and its significance for the worshippers were that they had faith in it. The denominator in the worship of all gods and spirits everywhere is faith. The power of an image was believed to be more real than that of a living being. The Yoruba appear to be satisfied with the gods with whom they are in immediate touch because they believe that when the Orisa have been worshipped, they will transmit what is necessary to Olodumare. This paper examines the traditional practices of the people of Yewa and discovers why Esu is market appellate. It focuses on the classifications of the forms and functions of Esu-Oja representational objects in selected towns in Yewaland. Keywords: appellate, classifications, divinities, fragment, forms, images, libations, mystical powers, Olodumare, representational, sacred, sacrifices, shrine, spirit archetype, transmission and transformation. Introduction Yewa which was formally called there are issues of intra-regional “Egbado” is located on Nigeria’s border conflicts that call for urgent attention. with the Republic of Benin. Yewa claim The popular decision to change the common origin from Ile-Ife, Oyo, ketu, Egbado name according to Asiwaju and Benin. -

Land Accessibility Characteristics Among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria

Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences 2(1): 1-12, 2017; Article no.ARJASS.30086 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Land Accessibility Characteristics among Migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria Gbenga John Oladehinde 1* , Kehinde Popoola 1, Afolabi Fatusin 2 and Gideon Adeyeni 1 1Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State Nigeria. 2Department of Geography and Planning Sciences, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out collaboratively by all authors. Author GJO designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors KP and AF supervised the preparation of the first draft of the manuscript and managed the literature searches while author GA led and managed the data analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ARJASS/2017/30086 Editor(s): (1) Raffaela Giovagnoli, Pontifical Lateran University, Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano 4, Rome, Italy. (2) Sheying Chen, Social Policy and Administration, Pace University, New York, USA. Reviewers: (1) F. Famuyiwa, University of Lagos, Nigeria. (2) Lusugga Kironde, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17570 Received 16 th October 2016 Accepted 14 th January 2017 Original Research Article st Published 21 January 2017 ABSTRACT Aim: The study investigated challenges of land accessibility among migrants in Yewa North Local Government Area of Ogun State, Nigeria. Methodology: Data were obtained through questionnaire administration on a Migrant household head. Multistage sampling technique was used for selection of 161 respondents for the study. -

A Journal of African Studies

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title The Persistence of Colonial Thinking in African Historiography: A Case Study Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0w12533q Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 7(2) ISSN 0041-5715 Author O'Toole, Thomas Publication Date 1977 DOI 10.5070/F772017423 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 43 TI1E PE~ISlENCE OF ~IAL TI11NKING IN AFRICPN HISTORIOGRWHY: A CASE SnJDY by Thanas o' Toole Introduction Though historical writing about Africa has nultiplied in both quantity and quality in the past fifteen years, IIU.lch of it still bears a oolonial flavor. One major difficulty faced by those who wish to teach a deoolonized history of Africa is the persistence of oolonial-inspired thinking of many African scholars . 1 Many European educated Africans seem to suffer fran a peculiar love-hate schizcphrenia which results in their per petuation of oolonial viewpoints to the present. 2 This article maintains that it is irrp)rtant for teachers aiXl students of African histo:ry to oonsider the paradigms3 through which historians of Africa filter their data. Such an explanation-fonn4 tmderlying a single historical essay is pre sented in order to identify the persistence of the oolonial para digm in this particular autror' s thinking aiXl to reveal the pre sent inadequacies of this explanation-fonn in African historio graphy. A Case Study An essay by Dr. A.L. Mabog1mje in J.F. Ajayi and Michael Crowder, History of West Africa (1971) has been specifically chosen as a case study.S Ajayi and Crowder's text is an inpor tant reference work for teachers and serves as a general badc gro..url for all interested in west African studies. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Hausa Calligraphic and Decorative Traditions of Northern Nigeria: from the Sacred to the Social

islamic africa 8 (2017) 13-42 Islamic Africa brill.com/iafr Hausa Calligraphic and Decorative Traditions of Northern Nigeria: From the Sacred to the Social Mustapha Hashim Kurfi African Studies Center, Boston University [email protected] Abstract In the past, sacred Islamic calligraphies were used strictly in sacred places, whereas profane calligraphies were used in secular spheres. However, the trend now among some Hausa artists is to extend the sacred Islamic calligraphic tradition to the social domain. Some Hausa calligraphers do so by “desacralizing” their Islamic-inspired cal- ligraphies. This article deals with the extension of Islamic decorations to secular social domains in Kano, Northern Nigeria. Such works are produced by calligraphers like Sha- ru Mustapha Gabari. I show how Hausa calligraphers like Mustapha Gabari creatively extend their arts, talents, and skills to other social domains. These domains include the human body, clothing, houses, and other objects. This article describes the ways in which the sacred and the secular realms overlap, and illustrates some key processes of enrichment the Islamic arts have undergone in sub-Saharan Africa. These processes exemplify the ʿAjamization of Islamic arts in Africa, especially how sub-Saharan African Muslims continue to creatively appropriate and enrich the Islamic calligraphic and decorative traditions to fit their local realities and address their preoccupations. Keywords ʿAjamization – Calligraphy – Hausa – Decoration – Sacred – Desacralized – Enrichment * I am indebted to Professor Fallou Ngom for introducing me to the field of ʿAjamī studies and for his unalloyed support to the realization of this volume. I also want to express my profound gratitude to Professors Steve Howard and Scott Reese; Dr. -

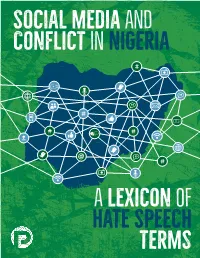

A Lexicon of HATE Speech Terms Table of Contents

SOciAL MEDIa AND CoNFLIcT IN Nigeria A LEXIcON OF HATE SPEeCH TeRMs Table of Contents I. Introduction ..........................................................................................................2 II. The Lexicon ..........................................................................................................3 Conflict in Nigeria: A Summary .................................................................................... 4 Words and Phrases That Are Offensive and Inflammatory ........................................ 7 Additional Words and Phrases That Are Offensive and Inflammatory .................... 29 Online Sources of Words and Phrases That Are Offensive and Inflammatory ........ 31 Sources of Words and Phrases in Traditional Media That Are Offensive and Inflammatory ....................................................................... 33 III. Annex A: Survey Methodology and Considerations ............................................34 IV. Annex B: Online Survey Questions .....................................................................36 V. Issues and Risks ..................................................................................................37 Endnotes ................................................................................................................39 Project Team: Theo Dolan, Caleb Gichuhi, YZ Ya’u, Hamza Ibrahim, Lauratu Umar Abdulsalam, Jibrin Ibrahim, Nohra Murad, Daniel Creed Lead Author: Will Ferroggiaro Copyeditor: Kelly Kramer 1 Graphic Designer: Kirsten Ankers, Citrine -

Fundamentalist Religious Movements : a Case Study of the Maitatsine Movement in Nigeria

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2004 Fundamentalist religious movements : a case study of the Maitatsine movement in Nigeria. Katarzyna Z. Skuratowicz University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Skuratowicz, Katarzyna Z., "Fundamentalist religious movements : a case study of the Maitatsine movement in Nigeria." (2004). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1340. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1340 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNDAMENTALIST RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE MAITATSINE MOVEMENT IN NIGERIA By Katarzyna Z. Skuratowicz M.S, University of Warsaw, 2002 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2004 FUNDAMENTALIST RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE MAITATSINE MOVEMENT IN NIGERIA By Katarzyna Z. Skuratowicz M.S., University of Warsaw, Poland, 2002 A Thesis Approved on April 20, 2004 By the Following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director Dr. Lateef Badru University of Louisville Thesis Associate Dr. Clarence Talley University of Louisville Thesis Associate Dr. -

156 the Syntactic Interference of Ika

THE SYNTACTIC INTERFERENCE OF IKA LANGUAGE ON ENGLISH PERFORMANCE OF IKA NATIVE SPEAKERS: A STUDY OF THE NOUN PHRASE STRUCTURE. Rosemary E. Chiedu Abstract This study examines the syntactic interference of Ika language on English performance of Ika native speakers using a noun phrase structure of both languages as the focus of analysis. Contrastive analysis of Ika and English noun phrase structures revealed that the syntactic structure of Ika and English Language at the simple noun phrase level cause interference LI (first language) on L2 (second language) and if not properly addressed, native speakers of Ika are likely to encounter problems whenever they want to use the noun phrase to make sentences in English Language. Ika language is a variety of the Igbo language spoken by people in Ika South, Ika North-East Local government area of Delta State and some few villages in Edo State. On the other hand , the English language is a prestigious language used in almost all parts of the world. As a result of the global spread , many varieties have evolved . The British Standard English (BrE) has international intelligibility and acceptability. Since the introduction of English by the British during the colonial period in Nigeria, it has performed numerous functions like the official language, language of integration, technology and most importantly, the language of education. The Concept of Interference The linguistics term 'interference' as it affects language learning and performance has been variously defined by linguists for a long time. Although the emphasis of their definitions are on the phonological level of language, today, the idea of linguistic interference goes beyond phonology to include a situation where the totality of the features of one language are carried , wholly or partially, over into another language thereby causing some kind of interference in reproducing or speaking that language (Conor, 1996).