Central Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intentions of Right-Wing Extremists in Germany

IOWA STATE UNIVERSITY Intentions of Right-wing Extremists in Germany Weiss, Alex 5/7/2011 Since the fall of the Nazi regime, Germany has undergone extreme changes socially, economically, and politically. Almost immediately after the Second World War, it became illegal, or at least socially unacceptable, for Germans to promote the Nazi party or any of its ideologies. A strong international presence from the allies effectively suppressed the patriotic and nationalistic views formerly present in Germany after the allied occupation. The suppression of such beliefs has not eradicated them from contemporary Germany, and increasing numbers of primarily young males now identify themselves as neo-Nazis (1). This group of neo-Nazis hold many of the same beliefs as the Nazi party from the 1930’s and 40’s, which some may argue is a cause for concern. This essay will identify the intentions of right-wing extremists in contemporary Germany, and address how they might fit into Germany’s future. In order to fully analyze the intentions of right-wing extremists today, it is critical to know where and how these beliefs came about. Many of the practices and ideologies of the former Nazi party are held today amongst contemporary extreme-right groups, often referred to as Neo-Nazis. A few of the behaviors of the Neo-Nazis that have been preserved from the former Nazi party are anti-Semitism, xenophobia and violence towards “non-Germans”, and ultra- conservatism (1). The spectrum of the right varies greatly from primarily young, uneducated, violent extremists who ruthlessly attack members of minority groups in Germany to intellectuals and journalists that are members of the New Right with influence in conservative politics. -

Morina on Forner, 'German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics After 1945'

H-German Morina on Forner, 'German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics after 1945' Review published on Monday, April 18, 2016 Sean A. Forner. German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics after 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. xii +383 pp. $125.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-107-04957-4. Reviewed by Christina Morina (Friedrich-Schiller Universität Jena) Published on H-German (April, 2016) Commissioned by Nathan N. Orgill Envisioning Democracy: German Intellectuals and the Quest for Democratic Renewal in Postwar German As historians of twentieth-century Germany continue to explore the causes and consequences of National Socialism, Sean Forner’s book on a group of unlikely affiliates within the intellectual elite of postwar Germany offers a timely and original insight into the history of the prolonged “zero hour.” Tracing the connections and discussions amongst about two dozen opponents of Nazism, Forner explores the contours of a vibrant debate on the democratization, (self-) representation, and reeducation of Germans as envisioned by a handful of restless, self-perceived champions of the “other Germany.” He calls this loosely connected intellectual group a network of “engaged democrats,” a concept which aims to capture the broad “left” political spectrum they represented--from Catholic socialism to Leninist communism--as well as the relative openness and contingent nature of the intellectual exchange over the political “renewal” of Germany during a time when fixed “East” and “West” ideological fault lines were not quite yet in place. Forner enriches the already burgeoning historiography on postwar German democratization and the role of intellectuals with a profoundly integrative analysis of Eastern and Western perspectives. -

Llf Lli) $L-Rsijii.II(Ill WJIITIW&. If(Fl" -!31F Lhli Wref-1Iiq RI) (Awmw

Llf llI) $l-rsIjii.II(ill WJIITIW&. If(fl" - !31f LhLI WrEf-1iIQ RI) (aWMW LtJJIflWiIJUIJ1JXI1IJ NiIV[Efl?#iUflhl GUIDE AND DIRECTORY FOR TRADING WITH GERMANY ECONOMIC COOPERATION ADMINISTRATION -SPECIAL MISSION TO GERMANY FRANKFURT, JUNE 1950 Distributed by Office of Small Business, Economic Cooperation Administration, Wasbington 25, D.C. FOREWORD This guide is published under the auspices of the Small Bus iness Program of the'Economic Cooperation Administration. It is intended to assistAmerican business firms, particularlysmaller manufacturingand exporting enterprises,who wish to trade or expandtheirpresent tradingrelationswith Western Germany. This guide containsa summary of economic information reg ardingWestern Germany,togetherwith data concerningGerman trade practicesand regulations,particularlythose relatingto the import of goods from the United States financed withECA funds. At the end of the manual are appendicesshowing names and add resses of agencies in Western Germany concerned rodh foreign trade and tables of principalGerman exports and imports. The ECA Special Mission to Germany has endeavored to present useful, accurate,and reliableinformationin this manual. Nothing contained herein, however, should be construed to supersede or modify existing legislationor regulationsgoverning ECA procurement or trade with Western Germany. Sources of information contained herein, such as lists of Western German trade organizations,are believed to be complete, but the Mission assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for the reliabilityof any agencies named. ADDENDUM The following information has been received -during the printing of this manual: 1. American businessmen interested in trading with Germany may consult the newly formed German-American Trade Promotion Company (Ge sellschaftzurFdrderungdesdeutsch-amerikanischen Handels), located at Schillerstrasse I, Frankfurt am Main, Germany. -

16/184 - Beschlussempfehlung Des Ausschusses Für Soziales, Frauen, Familie Und Tagesordnungspunkt 18: Gesundheit - Drs

(Ausgegeben am 16. Oktober 2008) Niedersächsischer Landtag Stenografischer Bericht 18. Sitzung Hannover, den 8. Oktober 2008 Inhalt: 100. Geburtstag des ehemaligen Ministerpräsi- Elke Twesten (GRÜNE)......................................2000 denten Heinrich Hellwege - Begrüßung durch Land- Ursula Körtner (CDU)...............................2001, 2003 tagspräsident Hermann Dinkla - Rede des Staats- Filiz Polat (GRÜNE)............................................2002 sekretärs a. D. Professor Dr. Johann Hellwege - Vor- trag von Professor Dr. Thomas Vogtherr, Vorsitzen- b) Diskriminierende Schwangerschaftstests - der der Historischen Kommission für Niedersachsen Toleriert Frauenministerin Ross-Luttmann Druck und Bremen ............................................................. 1981 auf Schwangere? - Anfrage der Fraktion der SPD - Präsident Hermann Dinkla ......................1981, 1993 Drs. 16/528...............................................................2004 Professor Dr. Johann Hellwege, Staatssekretär Ulla Groskurt (SPD) .................................2004, 2007 a. D................................................................ 1983 Mechthild Ross-Luttmann, Ministerin für Sozia- Professor Dr. Thomas Vogtherr, Vorsitzender les, Frauen, Familie und Gesundheit der Historischen Kommission für Nieder- ........................................................ 2005 bis 2011 sachsen und Bremen e.V. ............................. 1989 Helge Limburg (GRÜNE) ...................................2006 Ina Korter (GRÜNE)............................................2006 -

Jürgen Habermas and the Third Reich Max Schiller Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2012 Jürgen Habermas and the Third Reich Max Schiller Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Schiller, Max, "Jürgen Habermas and the Third Reich" (2012). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 358. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/358 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction The formation and subsequent actions of the Nazi government left a devastating and indelible impact on Europe and the world. In the midst of general technological and social progress that has occurred in Europe since the Enlightenment, the Nazis represent one of the greatest social regressions that has occurred in the modern world. Despite the development of a generally more humanitarian and socially progressive conditions in the western world over the past several hundred years, the Nazis instigated one of the most diabolic and genocidal programs known to man. And they did so using modern technologies in an expression of what historian Jeffrey Herf calls “reactionary modernism.” The idea, according to Herf is that, “Before and after the Nazi seizure of power, an important current within conservative and subsequently Nazi ideology was a reconciliation between the antimodernist, romantic, and irrantionalist ideas present in German nationalism and the most obvious manifestation of means ...modern technology.” 1 Nazi crimes were so extreme and barbaric precisely because they incorporated modern technologies into a process that violated modern ethical standards. Nazi crimes in the context of contemporary notions of ethics are almost inconceivable. -

Persistence and Activation of Right-Wing Political Ideology

Persistence and Activation of Right-Wing Political Ideology Davide Cantoni Felix Hagemeister Mark Westcott* May 2020 Abstract We argue that persistence of right-wing ideology can explain the recent rise of populism. Shifts in the supply of party platforms interact with an existing demand, giving rise to hitherto in- visible patterns of persistence. The emergence of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) offered German voters a populist right-wing option with little social stigma attached. We show that municipalities that expressed strong support for the Nazi party in 1933 are more likely to vote for the AfD. These dynamics are not generated by a concurrent rightward shift in political attitudes, nor by other factors or shocks commonly associated with right-wing populism. Keywords: Persistence, Culture, Right-wing ideology, Germany JEL Classification: D72, N44, P16 *Cantoni: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat¨ Munich, CEPR, and CESifo. Email: [email protected]. Hagemeister: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat¨ Munich. Email: [email protected]. Westcott: Vivid Economics, Lon- don. Email: [email protected]. We would like to thank Leonardo Bursztyn, Vicky Fouka, Mathias Buhler,¨ Joan Monras, Nathan Nunn, Andreas Steinmayr, Joachim Voth, Fabian Waldinger, Noam Yuchtman, Ekaterina Zhuravskaya and seminar participants in Berkeley (Haas), CERGE-EI, CEU, Copenhagen, Dusseldorf,¨ EUI, Geneva, Hebrew, IDC Herzliya, Lund, Munich (LMU), Nuremberg, Paris (PSE and Sciences Po), Passau, Pompeu Fabra, Stock- holm (SU), Trinity College Dublin, and Uppsala for helpful comments. We thank Florian Caro, Louis-Jonas Hei- zlsperger, Moritz Leitner, Lenny Rosen and Ann-Christin Schwegmann for excellent research assistance. Edyta Bogucka provided outstanding GIS assistance. Financial support from the Munich Graduate School of Economics and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through CRC-TRR 190 is gratefully acknowledged. -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Vpliv Rudolfa Augsteina Na Spiegel

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Tomaž Vodeb Vpliv Rudolfa Augsteina na Spiegel Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2010 UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Tomaž Vodeb Mentor: izr. prof. dr. Jernej Pikalo Vpliv Rudolfa Augsteina na Spiegel Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2010 ZAHVALA Iskreno se zahvaljujem mentorju prof. dr. Jerneju Pikalu za vse strokovne nasvete in velikodušno vsestransko pomoč pri izdelavi diplomskega dela. Zahvaljujem se tudi staršem, ki so mi omogočili študij in mi v težkih trenutkih vedno stali ob strani. Vpliv Rudolfa Augsteina na Spiegel Rudolf Augstein je eden najpomebnejših novinarjev povojne Nemčije.V diplomski nalogi analiziram njegovo pisanje in vpletenost v povojni politični prostor. Analiza poteka od začetka oz. ustanavljanja tednika vse do afere Spiegel, njenega poteka in posledic, ki so ključno spremenili družbeno okolje ne samo v Nemčiji. On in njegov tednik imata velik vpliv na razvoj socialne države iz pretežno uspešnega modela gospodarskega čudeža. V diplomski nalogi se osredotočam na Spiegel, ki je nastal v porušenem Hannovru s pomočjo Rudolfa Augsteina in njegovih mladih, iz vojne prispelih urednikov, tedensko izhajajoči Institut brez spoštovanja, ki ni kritiziral samo novo nastale demokracije, ostanke prejšnjega sistema, ampak tudi okupacijsko silo. Diploma preučuje človeka, ki je ustvaril Spiegel, kot tudi zgodovinski čas po drugi svetovni vojni v Nemčiji, ki je povezan tako z gospodarskim čudežem kot tudi s stalnim soočanjem z zgodovino. V nalogi ugotavljam, da je bil Augstein kompleksna oseba z veliko avtoritete v medijskem in tudi političnem svetu. Dognanja naloge dokazujejo, da je Augstein imel velik vpliv tudi širše, kar nakazuje tudi na to, da mediji pridobivajo na moči v novo nastali demokraciji v povojni Nemčiji. -

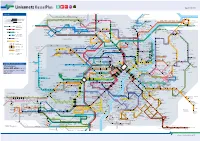

Liniennetz Kasselplus Stand: 13.12.2020

Liniennetz KasselPlus Stand: 13.12.2020 Grebenstein Hofgeismar / Warburg Legende Volkmarsen 40 Kleebergstraße Weser Ober- Abzw. Siedlung Brücke meiser Mitte Mühlenberg Westuffeln 130 Raiffeisen Mitte Werra Weidestraße Holzhausen 130 CALDEN Süd Goethe- ESPENAU Mitte Schloss KasselPlus-Gebiet Ehrsten Siedlung Hauptstraße Ulmenweg 46 Görlitzer Straße 30 46 46 Espenau- Bahnhof straße Siedlung 46 Abzweig Schachter Mönchehof 47 Rothwesten Stadtgebiet Kassel Schutzhof Fürstenwalder Konzert- Kirche Flughafen Kassel 47 100 Oberweg Winterbühren Wilhelms- Kurhessen- Schröder- Wildemann- Pionier- Mitscherlichstraße Straße scheune Straße Mitte 40 Sonnenallee Elsterbach häuser Straße straße straße schlucht brücke 42 Meinbressen Terminal 130 Am Mönchshaus Thüringer HANN. MÜNDEN NVV-Region Gasthaus Rathaus Buchenstraße Neue Straße 40 Siedlung Am Fliegerhorst Rotunde Feuerteich Siedlung Straße B3 Wilhelmshöhe Abzweig Fulda 30 42 101 102 103 Mitte Kastanienweg Raiffeisen- Bahnhof Fürsten- Schäfer- Mönchehof Gut Eichenberg wald Wilhelmsthaler Straße Weimarer 1 47 Vellmar-Nord Friedhof bank 104 105 120 190 195 Korbach RB4 100 Gerhard- Am Dornbusch berg RT1 Göttingen / RT4 Brandenburger Kaiserplatz 40 Mitte 42 RE2 • RE9 • RB83 Regionalzug/ Wolfhagen Mittel- Weg Hauptmann- Halle / Erfurt RB1 RE30 RE30 · RB1 Calden- 46 AHNATAL straße Straße RE11 • RE17 Frommershausen Musikerviertel Bergstraße Bgm.-Franz- Hann. Münden RegionalExpress 47 Schäferberg Straße Straße Abzweig Knickhagen Kasseler Straße Fürstenwald 48 Wilhelmsthal Bonaforth 30 Königs- Espenauer Mozart- -

Annual Report 2017

Annual Report 2017 Program Cover.indd 1 05/10/17 7:26 PM Table of Contents Minutes of the 132nd Business Meeting ................................................................................. 2 Officers’ Reports .................................................................................................................... 7 Professional Division Report ...................................................................................................... 8 Research Division Report ......................................................................................................... 10 Teaching Division Report ......................................................................................................... 12 American Historical Review Report .......................................................................................... 15 AHR Editor’s Report ............................................................................................................. 15 AHR Publisher’s Report ....................................................................................................... 31 Pacific Coast Branch Report ................................................................................................. 48 Committee Reports .............................................................................................................. 50 Committee on Affiliated Societies Report ............................................................................... 51 Committee on Gender Equity Report ..................................................................................... -

Bibliothek Stadtarchiv/Stadtmuseum 01.08.2016

Stadt Dinslaken - Bibliothek Stadtarchiv/Stadtmuseum 01.08.2016 Internationale Wochenschrift für Wissenschaft, Kunst u. Technik - Berlin : Scherl Deutschl Bc Zeit M Duisburg Ba Büro Verwaltung Köln M 10 U Rheinland Ce "Rot Rheinberg B Zu N 9. November 1938 - 9. November 1988 - Programm zum 50. Jahrestag der Duisburg B 9. N Progromnacht im Deutschen Reich : Oktober bis Dezember 1988 in Duisburg, Oberhausen, Mülheim, Dinslaken. - Rheinland Bg 20 M Kleve A 25 J 25 Jahre Rheinisches Freilichtmuseum Kommern. - Köln : Rheinland Verlag . - 171 Kommern Ag S.:Ill.(S/W) - ISBN 3-7927-07445-4 Büro Verwaltung Deutschl Kg 50 J 50 Jahre ThyssenKrupp Konzernarchiv. Duisburg : ThyssenKrupp Deutschl Bg Jahr Konzernarchiv . - 256 S. : Ill. - ISBN 3-931875-05-9 50 Jahre Verein für Heimatpflege und Verkehr Voerde e.V.. - Krefeld : Acken Z 0002/2001 B5 (1/2001). - S.36 75 Jahre Niederberg : Chronik der Schachtanlage Niederberg - 1911-1986. - . - Neuk-Vluyn C 75 J 223S.: Ill. (S/W) 75 Jahre Steinkohlenbergwerk Lohberg : 1909-1984. - . - 94S.: Ill. Din-Lohberg C 75 Jahre Straßenbahn in Duisburg : 1881-1956. - . - 78S.: Ill. (S/W) Duisburg C 75 J Krefeld C Jahr 125 Jahre Stadt Gummersbach - Dokumente zur Stadtgeschichte : Ausstellung Gummersbach B der Stadt Gummersbach und der Archivberatungsstelle Rheinland in der 12 Sparkasse Gummersbach vom 28. April bis 18. Mai 1982. - . - 29S. Seite 1 Stadt Dinslaken - Bibliothek Stadtarchiv/Stadtmuseum 01.08.2016 Kerpen L 150 160 Jahre Evangelische Stadtschule Pestalozzischule. - Dinslaken . - 18S. Dinslaken E 160 Deutschl Ka 313 400 Jahre Schule im Dorf 1585-1985 : Festschrift der Dorfschule Hiesfeld. - Din-Hiesfeld E 400 Dinslaken . - 112 S. : Ill. 550 Jahre Bruderschaften in Aldekerk : Festschrift zum 550. -

Die Deutsche Misere

Die deutsche Misere Geschichte eines Narrativs Von der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinisch-Westfälischen Technischen Hochschule Aachen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Sascha Penshorn Berichter: Universitätsprofessor Dr. Drs. h.c. Armin Heinen Universitätsprofessor em. Dr. Helmut König Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 5. März 2018 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Universitätsbibliothek online verfügbar. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung........................................................................................................................................5 2 Begründung einer Tradition: Grundlagen des Misere-Narrativs im Vormärz..............................22 2.1 "Salto Mortale" Die deutsche Misere als dialektische Figur.................................................22 2.1.1 Faust als mythische Verdichtung deutscher Geschichte................................................22 2.1.2 Hegels Geschichtsphilosophie.......................................................................................25 2.1.3 Der Junghegelianismus..................................................................................................27 2.1.4 "Germanische Urwälder": Das rückständige Deutschland als politische Realität.........29 2.1.5 Die Perspektive des Exils ..............................................................................................33 2.1.6 Die Idee der deutschen Misere bei Heine, Hess, Engels und Marx ..............................34