GOLDBERG VARIATIONS - English Suite No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J. S. BACH English Suites Nos

J. S. BACH English Suites Nos. 4–6 Arranged for Two Guitars Montenegrin Guitar Duo Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) with elegantly broken chords. This is interrupted by a The contrasting pair of Gavottes with a perky walking bass English Suites Nos. 4–6, BWV 809–811 sudden burst of semiquavers leading to a moment’s accompaniment brings in the atmosphere of a pastoral reflection before plunging into an extended and brilliant dance in the market square. The second Gavotte evokes (Arranged for two guitars by the Montenegrin Guitar Duo) fugal Allegro. Of the Préludes in the English Suites this is images of wind instruments piping together in rustic chorus. The English Suites is the title given to a set of six suites for Bach scholar, David Schulenberg has observed that while the longest and most elaborate. The Allemande which The Gigue, in 12/16 metre, is virtuosic in both keyboard believed to have been composed between 1720 the beginning of the Gigue presents a normal three-part follows is, in comparison, an oasis of calm, with superb compositional aspects and the technical demands on the and the early 1730s. During this period, Bach also explored fugal exposition, from then on, no more than two voices are contrapuntal writing and ingenious tonal modulations. The performers. Bach’s incomparable art of fugal writing is at the suite form in the six French Suites and the seven large heard at a time. Courante unites a French-style melodic line with a full stretch here, the second half representing, as in mirror suites under the title of Partitas (six in all) and an English Suite No. -

Information, Pictures, and Our Audio Archive Online Mikkelsen (1979 Frobenius/Simon Peter's Church, Kolding, Denmark) Point CD-5104

PROGRAM NO. 0614 4/3/2006 SAMUEL SCHEIDT: Variations on Christ lag it JACOBUS KLOPPERS: Two Jigs, fr Celtic E. Power to the People . a continuing centennial Todesbanden -Elizabeth Harrison (1984 Impressions -Gayle Martin (2002 Casavant/ tribute to one of the most influential and effective Fisk/Memorial Church, Stanford University, CA) Mount Allison University Chapel, Sackville, New advocates for the pipe organ, the late, great E. Raven CD-540 Brunswick, Canada) GHM Productions CD-003 (Edward George) Power Biggs (March 29, 1906- BASIL HARWOOD: In Exitu Israel (Voluntary for CLAUDE DEBUSSY: Arabesque No. 2 -Wolfram March 10, 1977). Eastertide) -Jeremy Filsell (1986 Harrison/ Adolph (1899 Didier/Notre Dame Cathedral, Winchester Cathedral, England) Herald CD-162 Laon, France) IFO CD-999 With the cheery, trend-setting sounds of his LOWELL MASON (arr. Martin): When I survey EUGENE GIGOUT: Fugue in E -Gerard Brooks Flentrop organ at Harvard's Busch-Reisinger the wondrous cross -Modern Brass Quintet; Kirk (1899 Didier/Notre Dame Cathedral, Laon) Museum, Biggs championed the 'classic' organ and Choir/Gregory Norton, conductor; Daniel Kerr Priory CD-764 its solo repertoire. But he also explored other (1961 Aeolian-Skinner/ Pasadena Presbyterian SIGFRID KARG-ELERT: Sphärenmusik, Op. 66, music, including works with brasses, orchestras, Church, CA) Arkay CD-6158 no. 2 -Natalie Clifton-Griffith, soprano; Rachel choirs, and composers outside the classic canon. Gough, violin; Rupert Gough (1931 Compton/ Details tba. Downside Abbey, Bath, England) PROGRAM NO. 0616 4/17/2006 Lammas CD-186 Going On Record . a springtime review of some TALIVALDIS KENINS: Toccata on Beautiful PROGRAM NO. 0615 4/10/2006 interesting new CD releases of organ music from Savior -Vita Kalnciema (1883 Walcker/Riga Easter Uprising . -

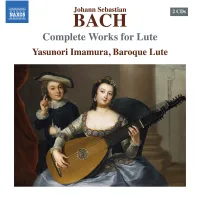

Imamura-Y-S03c[Naxos-2CD-Booklet

573936-37 bk Bach EU.qxp_573936-37 bk Bach 27/06/2018 11:00 Page 2 CD 1 63:49 CD 2 53:15 CD 2 Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 1Partita in E major, BWV 1006a 20:41 1Suite in E minor, BWV 996 18:18 # # Prelude 2:51 Consider, O my soul 2 Prelude 4:13 2 Betrachte, meine Seel’ Allemande 3:02 3 Loure 3:58 3 Betrachte, meine Seel’, mit ängstlichem Vergnügen, Consider, O my soul, with fearful joy, consider, Courante 2:40 4 Gavotte en Rondeau 3:29 4 Mit bittrer Lust und halb beklemmtem Herzen in the bitter anguish of thy heart’s affliction, Sarabande 4:24 5 Menuet I & II 4:43 5 Dein höchstes Gut in Jesu Schmerzen, thy highest good is Jesus’ sorrow. Bourrée 1:33 6 Bourrée 1:51 6 Wie dir auf Dornen, so ihn stechen, For thee, from the thorns that pierce Him, Gigue 2:27 Gigue 3:48 Die Himmelsschlüsselblumen blühn! what heavenly flowers spring. Du kannst viel süße Frucht von seiner Wermut brechen Thou canst the sweetest fruit from his wormwood gather, 7Suite in C minor, BWV 997 22:01 7Suite in G minor, BWV 995 25:15 Drum sieh ohn Unterlass auf ihn! then look on Him for evermore. Prelude 6:11 8 Prelude 3:11 8 Allemande 6:18 9 Fugue 7:13 9 Sarabande 5:28 0 Courante 2:35 Recitativo from St Matthew Passion, BWV 244b 0 $ $ Gigue & Double 6:09 ! Sarabande 2:50 Gavotte I & II 4:43 Ja freilich will in uns Yes! Willingly will we ! @ Prelude in C minor, BWV 999 1:55 Gigue 2:38 Ja freilich will in uns das Fleisch und Blut Yes! Willingly will we, Flesh and blood, Zum Kreuz gezwungen sein; Be brought to the cross; @ Fugue in G minor, BWV 1000 5:46 #Arioso from St John Passion, BWV 245 2:24 Je mehr es unsrer Seele gut, The harsher the pain Arioso: Betrachte, meine Seel’ Je herber geht es ein. -

Southern California Junior Bach Festival

The SCJBF 3 year, cyclical repertoire list for the Complete Works Audition Students may enter the Complete Works Audition (CWA) only once each year as a soloist on the same instrument and must perform the same music in the same category that they performed at the Branch and Regional Festivals, but complete as indicated on this list. Students will be disqualified if photocopied music is presented to the judges or used by accompanists (with the exception of facilitating page turns). Note: Repertoire lists for years in parentheses are not finalized and are subject to change Category I – SHORT PRELUDES AND FUGUES Year Composition BWV Each year Select any two of the following: Preludes: BWV 924-943 and 999 Fugues: BWV 952, 953 and 961 Select one of the following: 1. Prelude and Fugue in a m 895 2. Prelude and Fughetta in d m 899 3. Prelude and Fugue in e m 900 4. Prelude and Fughetta in G M 902 Category II – VARIOUS DANCE MOVEMENTS The dance movements listed below – from one of the listed Suites or Partitas – are required for the Complete Works Audition. Year Composition BWV 2021 English Suites: 1. From the A Major #1 806 The Bourree I and the Bourree II 2. From the e minor #5 810 The Passepied I and the Passepied II French Suites: 1. From the d minor #1 812 The Menuet I and the Menuet II 2. From the G Major #5 816 The Gavotte, Bourree and Loure Partitas: 1. From the a min or #3 827 The Burlesca and the Scherzo 2. -

Download Programme

TWICKENHAM5 CHORAL SOCIETY ISRAEL IN EGYPT Soprano: Mary Bevan Alto: Roderick Morris Tenor: Nathan Vale Brandenburg Baroque Sinfonia conducted by Christopher Herrick All Saints Church, Kingston Saturday 4 July 2015 Would you like to see your company here? . Take advantage of our competitive rates . Advertise with the TCS . Put your products and services before a large and discerning audience Email [email protected] for more details. A Catholic school warmly welcoming girls of all faiths, age 3 – 18 Visits to Prep and Senior Departments on alternate Wednesdays. Please call us on 020 3261 0139 Email: [email protected] www.stcatherineschool.co.uk THE FRAMING COMPANY Bespoke Picture Framing 6 FIFE ROAD KINGSTON KT1 1SZ 020 8549 9424 www.the-framing-company.com FUTURE CONCERTS AND EVENTS Thursday 10 September 2015, St Martin-in-the-Fields, 7pm MOZART: Requiem Brandenburg Sinfonia Sunday 11 October 2015, Landmark Arts Centre, Teddington, 7.30pm A concert as part of the Richmond Festival of Music and Drama, celebrating the borough hosting several matches of the Rugby World Cup 2015 VIVALDI: Gloria MOZART: Requiem Emily Vine, Freya Jacklin, Daniel Joy, Peter Lidbetter Brandenburg Sinfonia Saturday 12 December 2015, All Saints Church, Kingston, 7.30pm ROSSINI: Petite Messe Solennelle MENDELSSOHN: Hymn of Praise (arr Iain Farrington) Sarah Fox, Patricia Orr, Peter Auty, Jamie Hall Iain Farrington, piano and Freddie Brown, organ Saturday 9 April 2016, All Saints Church, Kingston, 7.30pm PIZZETTI: Missa di Requiem DURUFLÉ: Requiem Saturday 9 July 2016, St John’s Smith Square, 7.30pm ELGAR: Dream of Gerontius Miranda Westcott, Peter Auty, David Soar Brandenburg Sinfonia TCS is affiliated to Making Music, which represents and supports amateur performing and promoting societies throughout the UK Twickenham Choral Society is a registered charity, number 284847 The use of photographic video or audio recording equipment during the performance is not permitted without the prior approval of the Twickenham Choral Society. -

Ideazione E Coordinamento Della Programmazione a Cura Di Massimo Di Pinto Con La Collaborazione Di Leonardo Gragnoli

Ideazione e coordinamento della programmazione a cura di Massimo Di Pinto con la collaborazione di Leonardo Gragnoli gli orari indicati possono variare nell'ambito di 4 minuti per eccesso o difetto Martedì 7 febbraio 2017 00:00 - 02:00 euroclassic notturno schubert, franz (1797-1828) sei danze tedesche (D 820) orchestraz di anton webern dall'orig. per pf. in la bem mag - in la bem mag - in la bem mag - in si bem mag - in si bem mag - in si bem mag. luxembourg philharmonic orch dir. justin brown (reg. lussemburgo, 20/12/1996) durata: 8.56 RSL radio televisione lussemburghese larsson, lars-erik (1908-1986) croquiser, sei schizzi per pf op. 38 capriccioso - grazioso - semplice - scherzando - espressivo - ritmico. marten landström, pf durata: 11.59 SR radio svedese bruch, max (1838-1920) kol nidrei, per vcl e orch op. 47 adam krzeszowiec, vcl; polish radio symphony orch dir. lukasz borowicz (reg. varsavia, 21/04/2013) durata: 12.26 PR radio polacca poulenc, francis (1899-1963) sept chansons per coro la blanche neige - à peine défigurée - par une nuit nouvelle - tous les droits - belle et ressemblante - marie - luire. jutland chamber choir dir. mogens dahl durata: 12.59 DR radiotelevisione di stato danese händel, georg friedrich (1685-1759) concerto in si bem mag per arpa e orch op. 4 n. 6 (HWV 294) andante, allegro - larghetto - allegro moderato. sofija ristic, arpa; slovenian radio television symphony orch dir. pavle despalj durata: 13.06 RTVS radiotelevisione slovena elgar, edward (1857-1934) sea pictures op. 37 sea slumber song - in haven - sabbath morning at sea - where corals lie - the swimmer. -

Walton - a List of Works & Discography

SIR WILLIAM WALTON - A LIST OF WORKS & DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Martin Rutherford, Penang 2009 See end for sources and legend. Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Catalogue No F'mat St Rel A BIRTHDAY FANFARE Description For Seven Trumpets and Percussion Completion 1981, Ischia Dedication For Karl-Friedrich Still, a neighbour on Ischia, on his 70th birthday First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Recklinghausen First 10-Oct-81 Westphalia SO Karl Rickenbacher Royal Albert Hall L'don 7-Jun-82 Kneller Hall G E Evans A LITANY - ORIGINAL VERSION Description For Unaccompanied Mixed Voices Completion Easter, 1916 Oxford First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.03 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - FIRST REVISION Description First revision by the Composer Completion 1917 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.14 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - SECOND REVISION Description Second revision by the Composer Completion 1930 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel St Johns, Cambridge ? Jan-62 George Guest St Johns, Cambridge 01a ARG ZRG -

UMD NEWS SERVICE 724-8801, Ext 210 September 2, 1966 DULUTH

Release on receipt UMD NEWS SERVICE 724-8801, Ext 210 September 2, 1966 DULUTH -- As a student and teacher of baroque music (1700s), music styles and history, UMD Associate Professor C. Lindsley Edson inherited a per- former's desire for accuracy and precision and an "interest in (musical) in- struments of the time." The keyboard instrument of the baroque period was the harpischord. In his quest for authenticity, Edson took a sabbatical leave in England dur- ing 1964-65. While there he decided to purchase a harpsichord. When the instrument arrived on the ocean-going vessel Manchester Shipper in July via the St. Lawrence Seaway, the Edsons were settled in their new home at 3500 London Road and a special music room was ready. The harpsichord was made by Robert Goble & Son, Limited (Oxford, England) and, in contrast to the piano, the strings are plucked and not struck. It has a larger range than the piano and Edson's model has two keyboards. "You can create more dependable subtleties, combinations and tonal qualities on a harpsichord than are possible on a piano because the mechani- cal plucking of the strings is more accurate than the human touch," said Edson. He explained that the force with which each key of the harpsichord is struck does not matter, since each one of the plectrum (plucking devices) creates the same note strength as any other. There are five sets of plectrum and they engage the strings through the use of six pedals. "The pedals give you several interesting combinations," he said. "Actually, I have four harpsichords in one." Edson's music room is soundproof and has independent temperature control to protect the instrument. -

NFA Gift Oakes Collection.Xlsx

Title Creator bib. number Call Number Twenty‐four exercises :for the flute (in all major and minor keys), op. 33 Joachim Andersen. MT345 .A544 op. 33 F57 Georg Philipp Telemann herausgegeben im Auftrag der Gesellschaft für Musikalische Werke Musikforschung. M3 .T268 Jeux :sonatine pour flute et piano Jacques Ibert. M242 .I12j Trois pieces en courte‐pointe,pour flute et piano Jacques Chailley. .b27393860 M242 .C434 T 65 Aria for flute and piano,op. 48, no. 1. .b27394268 M242 .DF656 op. 48, no. 1 Quartett, D‐dur, für Flöte (Oboe), Violine, Viola (Horn) und Violoncello, op. VIII/1. Hrsg. von Walter Upmeyer. .b27982981 M462 .S783 op.8 no. 1 Sonatine Es‐durfür Cembalo (Klavier), 2 Flöten, 2 Violinen, Bratsche und Bass hrsg. von Fritz Oberdorffer. .b27996517 M722 .B116s E b maj. Concerto for flute and chamber orchestra, or flute and piano,MCMXXXXII op. 35 [by] Robert Casadesus. .b28016798 M1021 .C334 op.35 Sinfonien für Kammerorchester:E‐moll. Hrsg. von Raymond Meylan. Symphonies for chamber orchestra. .b28020832 M1105 .S286 S5 no.4 Concertino pour flute et orchestre a cordes, ou piano Antonio Szalowski. .b28037613 M1106 .S996 C74 Joh. Seb. Bach auf Grund der Ausgabe der Bachgesellschaft bearbeitet von Ausgewahlte Arien für Alt :mit obligaten Instrumenten und Klavier oder Orgel Eusebius Mandyczewski. .b28068075 M2103.3 .B118 A6 alto Sonate pour piano et flute :op. 52 Ch. Koechlin. .b30264923 M242 .K777 op.52 Melody for flute and piano : op. 35, no. 1 Reinhold Gliere [edited with special annotations by John Wummer] .b4067082x M242 .G545 op. 35 no. 1 1946 6 canonic sonatas :for two flutes Telemann [edited by] C. -

OCTOBER, 2012 Independent Presbyterian Church Birmingham

THE DIAPASON OCTOBER, 2012 Independent Presbyterian Church Birmingham, Alabama Cover feature on pages 26–28 THE DIAPASON Letters to the Editor A Scranton Gillette Publication One Hundred Third Year: No. 10, Whole No. 1235 OCTOBER, 2012 In the wind . and there are pointy-painful heat sinks Established in 1909 ISSN 0012-2378 John Bishop’s fascinating column (Au- (fi n-shaped radiators) across the back so An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, gust 2012) on electricity and wind in they’re awful to handle. the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music pipe organs misstates what rectifi ers and Yesterday, I installed a new rectifi er transformers do. A transformer takes an in an organ in Manhattan that was small AC voltage and changes it to another AC and light enough that I carried it in a voltage, e.g., 120 VAC to 12–16 VAC. A canvas “Bean Bag” on the subway along CONTENTS Editor & Publisher JEROME BUTERA [email protected] rectifi er then takes the stepped-down AC with my “city” tool kit. Obviously, there FEATURES 847/391-1045 voltage and rectifi es it to DC. It is that have been lots of changes in how “recti- DC which electrically powers the circuits fi ers” work, but whatever goes on inside, An Interview with Montserrat Torrent Associate Editor JOYCE ROBINSON of the organ. John has the functions of as long as they provide the power I need Queen of Iberian organ music [email protected] by Mark J. Merrill 19 transformers and rectifi ers reversed. to run an organ’s action I’m stuck with 847/391-1044 William Mitchell calling them “rectifi ers.” An American Organ Moves to Germany Contributing Editors LARRY PALMER Columbus, Ohio Mr. -

Kammerakademie Potsdam Trevor Pinnock Emmanuel Pahud

Kammerakademie Potsdam Orquestra de Câmara de Potsdam Trevor Pinnock regência Emmanuel Pahud flauta O MINISTÉRIO DA CULTURA, O GOVERNO DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO, A SECRETARIA DA CULTURA E A CULTURA ARTÍSTICA APRESENTAM MOMENTO MUSICAL Momento Musical do Le Concert de la Loge (foto Heloisa Bortz) Você conhece o Momento Musical? Sempre às 20h, antes de cada concerto da Temporada Cultura Artística, o jornalista e crítico musical Irineu Franco Perpetuo comenta de forma descontraída sobre os compositores, as obras e os intérpretes que se apresentam naquela noite. Participe deste encontro! realização MINISTÉRIO DA CULTURA Anúncio Momento Musical FINAL.indd 1 19/05/17 10:16 O Ministério da Cultura, o Governo do Estado de São Paulo, a Secretária da Cultura e a Cultura Artística apresentam Kammerakademie Potsdam Orquestra de Câmara de Potsdam Trevor Pinnock regência Emmanuel Pahud flauta PATROCÍNIO REALIZAÇÃO Gioconda Bordon 3 Programa 4 Notas sobre o programa 6 Mônica Lucas Biografias 13 SOCIEDADE DE CULTURA ARTÍSTICA DIRETORIA PRESIDENTE Antonio Hermann D. Menezes de Azevedo VICE-PRESIDENTE Gioconda Bordon DIRETORES Carlos Mendes Pinheiro Júnior, Fernando Lohmann, Gioconda Bordon, Ricardo Becker, Rodolfo Villela Marino SUPERINTENDENTE Frederico Lohmann CONSELHO DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO PRESIDENTE Fernando Carramaschi VICE-PRESIDENTE Roberto Crissiuma Mesquita CONSELHEIROS Antonio Hermann D. Menezes de Azevedo, Carlos José Rauscher, Francisco Mesquita Neto, Gérard Loeb, Henri Philippe Reichstul, Henrique Meirelles, Jayme Sverner, Marcelo Kayath, Milú Villela, -

Trevor Pinnock Journey

TREVOR PINNOCK JOURNEY Two Hundred Years of Harpsichord Music TREVOR PINNOCK JOURNEY Two Hundred Years of Harpsichord Music ANTONIO DE CABEZÓN (c.1510–1566) GIROLAMO FRESCOBALdi (1583–1643) 1. Diferencias sobre 15. Toccata nona ................................ 4:32 ‘El canto del caballero’ .................. 3:10 16. Balletto primo e secondo .............. 5:39 from Toccate d’intavolatura di cimbalo et WILLIAM BYRD (c.1540–1623) organo,1637 2. The Carman’s Whistle .................. 3:58 GEORGE FRIDERIC HAndel (1685–1759) THOMAS TaLLIS (c.1505–1585) 17. Chaconne in G major, HWV 435 ... 6:36 3. O ye tender babes ........................ 2:37 DOMENICO SCARLAtti (1685–1757) JOHN Bull (1562/3–1628) Three Sonatas in D major, K. 490–92 4. The King’s Hunt ............................ 3:25 18. Sonata, K. 490: Cantabile ............ 5:02 JAN PIETERSZOON SWEELINCK 19. Sonata, K. 491: Allegro ................ 4:57 (1562–1621) 20. Sonata, K. 492: Presto ................. 4:17 5. Variations on ‘Mein junges Leben hat ein End’, SwWV 324 .............. 6:10 Total Running Time: 68 minutes JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACh (1685–1750) French Suite No. 6 in E major, BWV 817 6. Prélude ......................................... 1:31 7. Allemande .................................... 3:28 8. Courante ...................................... 1:47 9. Sarabande ................................... 3:22 10. Gavotte ........................................ 1:07 11. Polonaise ...................................... 1:20 12. Bourrée ........................................ 1:41 13.