Ecstasy and the Concomitant Use of Pharmaceuticals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clopixol Acuphase®)

Guidelines for the use of zuclopenthixol acetate injection (Clopixol Acuphase®) Version 3.1 – January 2018 GUIDELINE REPLACED Version 3 RATIFYING COMMITTEE Drugs and Therapeutics Group DATE RATIFIED October 2015 NEXT REVIEW DATE January 2021 EXECUTIVE SPONSOR Executive Medical Director ORIGINAL AUTHOR Jed Hewitt – Chief Pharmacist Review / update – 2015 Helen Manuell – Lead Pharmacist (ESx) Review / update - 2018 Jed Hewitt – Chief Pharmacist If you require this document in an alternative format, i.e. easy read, large text, audio or Braille please contact the pharmacy team on 01243 623349. Guidelines for the use of zuclopenthixol acetate injection (Clopixol Acuphase®) Introduction In the past, Acuphase® has often been too widely and possibly inappropriately used, sometimes without full regard being given to the fact that it is a potentially hazardous and toxic preparation with very little published information to support its use. Indeed, the Cochrane Library concludes that there is inadequate data on Acuphase® and no convincing evidence to support its use in acute psychiatric emergency. So far as possible, it should therefore be reserved for the minority of patients who have a prior history of previous use and good response, with use defined in an advance directive. Similarly, as a general rule Acuphase® should not be used for rapid tranquillisation unless such practice is also in accordance with an advance directive. Normally, Acuphase® should never be considered as a first-line drug for rapid tranquillisation as its onset of action will often not be rapid enough in these circumstances. In addition, the administration of an oil-based injection carries very high risk in a highly agitated patient. -

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (Also Belong to Psychiatric Medication Category) • Codeine (In 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • codeine (in 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No. 1/2/3/4, Fiorinal® C, Benzodiazepines Codeine Contin, etc.) • heroin • alprazolam (Xanax®) • hydrocodone (Hycodan®, etc.) • chlordiazepoxide (Librium®) • hydromorphone (Dilaudid®) • clonazepam (Rivotril®) • methadone • diazepam (Valium®) • morphine (MS Contin®, M-Eslon®, Kadian®, Statex®, etc.) • flurazepam (Dalmane®) • oxycodone (in Oxycocet®, Percocet®, Percodan®, OxyContin®, etc.) • lorazepam (Ativan®) • pentazocine (Talwin®) • nitrazepam (Mogadon®) • oxazepam ( Serax®) Alcohol • temazepam (Restoril®) Inhalants Barbiturates • gases (e.g. nitrous oxide, “laughing gas”, chloroform, halothane, • butalbital (in Fiorinal®) ether) • secobarbital (Seconal®) • volatile solvents (benzene, toluene, xylene, acetone, naptha and hexane) Buspirone (Buspar®) • nitrites (amyl nitrite, butyl nitrite and cyclohexyl nitrite – also known as “poppers”) Non-Benzodiazepine Hypnotics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • chloral hydrate • zopiclone (Imovane®) Other • GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate) • Rohypnol (flunitrazepam) CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM STIMULANTS Amphetamines Caffeine • dextroamphetamine (Dexadrine®) Methelynedioxyamphetamine (MDA) • methamphetamine (“Crystal meth”) (also has hallucinogenic actions) • methylphenidate (Biphentin®, Concerta®, Ritalin®) • mixed amphetamine salts (Adderall XR®) 3,4-Methelynedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy) (also has hallucinogenic actions) Cocaine/Crack -

Review of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacogenetics in Atypical Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics

pharmaceutics Review Review of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacogenetics in Atypical Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics Francisco José Toja-Camba 1,2,† , Nerea Gesto-Antelo 3,†, Olalla Maroñas 3,†, Eduardo Echarri Arrieta 4, Irene Zarra-Ferro 2,4, Miguel González-Barcia 2,4 , Enrique Bandín-Vilar 2,4 , Victor Mangas Sanjuan 2,5,6 , Fernando Facal 7,8 , Manuel Arrojo Romero 7, Angel Carracedo 3,9,10,* , Cristina Mondelo-García 2,4,* and Anxo Fernández-Ferreiro 2,4,* 1 Pharmacy Department, University Clinical Hospital of Ourense (SERGAS), Ramón Puga 52, 32005 Ourense, Spain; [email protected] 2 Clinical Pharmacology Group, Institute of Health Research (IDIS), Travesía da Choupana s/n, 15706 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] (I.Z.-F.); [email protected] (M.G.-B.); [email protected] (E.B.-V.); [email protected] (V.M.S.) 3 Genomic Medicine Group, CIMUS, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] (N.G.-A.); [email protected] (O.M.) 4 Pharmacy Department, University Clinical Hospital of Santiago de Compostela (SERGAS), Citation: Toja-Camba, F.J.; 15706 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] Gesto-Antelo, N.; Maroñas, O.; 5 Department of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Technology and Parasitology, University of Valencia, Echarri Arrieta, E.; Zarra-Ferro, I.; 46100 Valencia, Spain González-Barcia, M.; Bandín-Vilar, E.; 6 Interuniversity Research Institute for Molecular Recognition and Technological Development, -

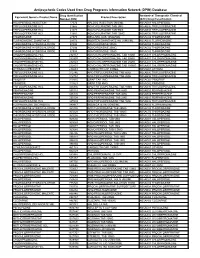

Antipsychotic Codes Used from Drug Programs Information Network (DPIN) Database

Antipsychotic Codes Used from Drug Programs Information Network (DPIN) Database Drug Identification Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Equivalent Generic Product Name Product Description Number (DIN) (ATC) Drug Classification HALOPERIDOL INJECTION 17574 HALDOL INJECTION 5MG/ML N05AD01 HALOPERIDOL TRIFLUOPERAZINE HCL 21865 NOVO-FLURAZINE TAB 2MG N05AB06 TRIFLUOPERAZINE TRIFLUOPERAZINE HCL 21873 NOVO-FLURAZINE TAB 5MG N05AB06 TRIFLUOPERAZINE TRIFLUOPERAZINE HCL 21881 NOVO-FLURAZINE TAB 10MG N05AB06 TRIFLUOPERAZINE THIORIDAZINE 27375 MELLARIL SUS 10MG/5ML N05AC02 THIORIDAZINE FLUPHENAZINE ENANTHATE 29173 MODITEN ENANTHATE INJ 25MG/ML N05AB02 FLUPHENAZINE THIORIDAZINE HYDROCHLORIDE 37486 NOVO-RIDAZINE 50MG N05AC02 THIORIDAZINE THIORIDAZINE HYDROCHLORIDE 37494 NOVO-RIDAZINE 25MG N05AC02 THIORIDAZINE THIORIDAZINE HYDROCHLORIDE 37508 NOVO-RIDAZINE 10MG N05AC02 THIORIDAZINE CHLORPROMAZINE HCL 232157 NOVO-CHLORPROMAZINE TAB 10MG N05AA01 CHLORPROMAZINE CHLORPROMAZINE HCL 232807 NOVO-CHLORPROMAZINE TAB 50MG N05AA01 CHLORPROMAZINE CHLORPROMAZINE HCL 232823 NOVO-CHLORPROMAZINE TAB 25MG N05AA01 CHLORPROMAZINE CHLORPROMAZINE HCL 232831 NOVO-CHLORPROMAZINE TAB 100MG N05AA01 CHLORPROMAZINE LITHIUM CARBONATE 236683 CARBOLITH CAP 300MG N05AN01 LITHIUM TRIFLUOPERAZINE HCL 312746 APO TRIFLUOPERAZINE TAB 5MG N05AB06 TRIFLUOPERAZINE TRIFLUOPERAZINE HCL 312754 APO TRIFLUOPERAZINE TAB 2MG N05AB06 TRIFLUOPERAZINE PIMOZIDE 313815 ORAP TAB 2MG N05AG02 PIMOZIDE PIMOZIDE 313823 ORAP TAB 4MG N05AG02 PIMOZIDE TRIFLUOPERAZINE HCL 326836 APO TRIFLUOPERAZINE TAB 10MG N05AB06 -

Guidance on the Treatment of Antipsychotic Induced Hyperprolactinaemia in Adults

Guidance on the Treatment of Antipsychotic Induced Hyperprolactinaemia in Adults Version 1 GUIDELINE NO RATIFYING COMMITTEE DRUGS AND THERAPEUTICS GROUP DATE RATIFIED April 2014 DATE AVAILABLE ON INTRANET NEXT REVIEW DATE April 2016 POLICY AUTHORS Nana Tomova, Clinical Pharmacist Dr Richard Whale, Consultant Psychiatrist In association with: Dr Gordon Caldwell, Consultant Physician, WSHT . If you require this document in an alternative format, ie easy read, large text, audio, Braille or a community language, please contact the Pharmacy Team on 01243 623349 (Text Relay calls welcome). Contents Section Title Page Number 1. Introduction 2 2. Causes of Hyperprolactinaemia 2 3. Antipsychotics Associated with 3 Hyperprolactinaemia 4. Effects of Hyperprolactinaemia 4 5. Long-term Complications of Hyperprolactinaemia 4 5.1 Sexual Development in Adolescents 4 5.2 Osteoporosis 4 5.3 Breast Cancer 5 6. Monitoring & Baseline Prolactin Levels 5 7. Management of Hyperprolactinaemia 6 8. Pharmacological Treatment of 7 Hyperprolactinaemia 8.1 Aripiprazole 7 8.2 Dopamine Agonists 8 8.3 Oestrogen and Testosterone 9 8.4 Herbal Remedies 9 9. References 10 1 1.0 Introduction Prolactin is a hormone which is secreted from the lactotroph cells in the anterior pituitary gland under the influence of dopamine, which exerts an inhibitory effect on prolactin secretion1. A reduction in dopaminergic input to the lactotroph cells results in a rapid increase in prolactin secretion. Such a reduction in dopamine can occur through the administration of antipsychotics which act on dopamine receptors (specifically D2) in the tuberoinfundibular pathway of the brain2. The administration of antipsychotic medication is responsible for the high prevalence of hyperprolactinaemia in people with severe mental illness1. -

Product Monograph

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH PrCLOPIXOL® Zuclopenthixol Tablets Lundbeck Std. (10 mg and 25 mg zuclopenthixol as zuclopenthixol hydrochloride) Lundbeck standard PrCLOPIXOL-ACUPHASE® 50 mg/mL Zuclopenthixol Intramuscular Injection (45.25 mg/mL zuclopenthixol as zuclopenthixol acetate) Lundbeck standard PrCLOPIXOL® DEPOT 200 mg/mL Zuclopenthixol Intramuscular Injection (144.4 mg/mL zuclopenthixol as zuclopenthixol decanoate) Lundbeck standard Antipsychotic Agent Lundbeck Canada Inc. Date of Revision: 2600 Alfred-Nobel October 16th, 2020 Suite 400 St-Laurent, QC H4S 0A9 Submission Control No : 171198 Page 1 of 34 Table of Contents PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION .........................................................3 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ........................................................................3 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ..............................................................................3 CONTRAINDICATIONS ...................................................................................................4 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ..................................................................................4 ADVERSE REACTIONS ....................................................................................................9 DRUG INTERACTIONS ..................................................................................................13 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ..............................................................................14 OVERDOSAGE ................................................................................................................18 -

Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period

Supplementary Online Content Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naïve patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. Published online July 11, 2016. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298. eTable 1. List of CPT Codes eFigure. Sample Construction Flow Chart eTable 2. List of Drug Classes eTable 3. List of Medical Comorbidities and ICD-9 Codes eTable 4. Sample Summary Characteristics, by procedure eTable 5. Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use Following Surgery Among Opioid Naïve Patients This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/29/2021 eTable 1. List of CPT codes CPT Codes Total Knee Arthroplasty1 27447 Total Hip Arthroplasty1 27130 Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy2 47562, 47563, 47564 Open Cholecystectomy3 47600, 47605, 47610 Laparoscopic Appendectomy4 44970, 44979 Open Appendectomy5 44950, 44960 Cesarean Section6 59510, 59514, 59515 FESS7 31237, 31240, 31254, 31255, 31256, 31267, 31276, 31287, 31288 Cataract Surgery8 66982, 66983, 66984 TURP9 52601, 52612, 52614 Simple Mastectomy10‐12 19301, 19302, 19303, 19180 © 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/29/2021 eFigure. Sample Construction Flow Chart © 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/29/2021 eTable 2. -

Psychiatric Medication Information / Arabic 1

AARRAABBIICC Professor David Castle Ms. Nga Tran St. Vincent’s Mental Health Level 2, 46 Nicholson Street, Fitzroy Vic 3065 (03) 9288 4147 (03) 9288 4751 Psychiatric Medication Information / Arabic 1 Psychiatric Medication Information / Arabic 2 dosette box blister pack Psychiatric Medication Information / Arabic 3 PRN ANTIPSYCHOTICS ANTIDEPRESSANTS SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors) SNRIs (Serotonin Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitors Psychiatric Medication Information / Arabic 4 Noradrenaline and Specific Serotonin Antagonists (NaSSAs) Noraderenaline Reuptake Inhibitors (NaRIs) NaSSAs NaRIs Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) MOOD STABILISERS Lithium Carbamazepine Sodium Valproate Anxiolytics Benzodiazepines benzhexol benztropine Anticholinergic drugs biperiden Beta Blockers Psychiatric Medication Information / Arabic 5 ® Chlorpromazine (Largactil ), Thioridazine (Aldazine®), Trifluoperazine (Stelazine®), Haloperidol ® ® ® (Serenace , Haldol ), Flupenthixol (Fluanxol ), Zuclopenthixol (Clopixol®) ® ® Risperidone (Risperdal ), Olanzapine (Zyprexa ), Quetiapine (Seroquel®), Clozapine Clozapine ® ® ® (Clopine /Clozaril ), Amisulpride (Solian ), Aripiprazole (Abilify®), Ziprasidone (Zeldox®), Paliperidone (Invega®) ® ® Imipramine (Tofranil ), Amitriptyline (Tryptanol ), Dothiepin (Prothiaden®), Doxepin (Sinequan®), ® ® Nortriptyline (Allegron ), Trimipramine (Surmontil ) (SSRIs) ® ® Fluoxetine (Prozac ), Sertraline (Zoloft ), Citalopram (Cipramil®), Paroxetine (Aropax®), Fluvoxamine ® ® (Luvox ), Escitalopram (Lexapro ) (SNRI) -

Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics. Review and Recent Developments

Review Article Monica Zolezzi, BPharm, MSc. ABSTRACT Long-acting injectable antipsychotics, also known as "depots", were developed in the late 1960s as an attempt to improve compliance and long-term management of schizophrenia. Despite their availability for over 30 years, guidelines for their use and data on patients for whom long-acting injectable antipsychotics are most indicated are sparse and vary considerably. A review of the perceived advantages and disadvantages of using long-acting injectable antipsychotics is provided in this article, as well as a review of the literature to update clinicians on the current advances of this therapeutic option to optimize compliance and long-term management of chronic schizophrenia. Neurosciences 2005; Vol. 10 (2): 126-131 chizophrenia is a chronic disorder for which it is hydrolyze the esterified compound and liberates the Swell recognized that lifelong treatment with parent antipsychotic.2,9,10 Although depot antipsychotics is necessary. Although quite antipsychotics have been available for over 30 successful in treating and preventing relapses,1,2 years, guidelines for their use and data on patients antipsychotics are not readily accepted by patients, for whom long-acting injectables are most indicated thus, non-compliance is common.3,4 Thus, are sparse and vary considerably. In addition, long-acting injectable forms of these medications despite the fact that the use of depot antipsychotics were developed in an attempt to help medication has been extensively promoted to overcome patient compliance -

Should Inverse Agonists Be Defined by Pharmacological Mechanism Or

CNS Spectrums,(2019), 24 354 – 370. © Cambridge University Press 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms , of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:10.1017/S1092852918001098 REVIEW ARTICLE Practical considerations for managing breakthrough psychosis and symptomatic worsening in patients with schizophrenia on long-acting injectable antipsychotics Christoph U. Correll ,1,2 Jennifer Kern Sliwa ,3* Dean M. Najarian ,3 and Stephen R. Saklad4 1 Department of Psychiatry and Molecular Medicine, Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine, Hempstead, New York 2 Division of Psychiatry Research, Zucker Hillside Hospital, Northwell Health, Glen Oaks, New York 3 Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC, Titusville, New Jersey 4 College of Pharmacy, Pharmacotherapy Division, University of Texas at Austin, San Antonio, Texas With more long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics available for treating schizophrenia, each with variable durations of action (2 weeks to 3 months), it is important to have clear management strategies for patients developing breakthrough psychotic symptoms or experiencing symptomatic worsening on LAIs. However, no treatment guidelines or clinical practice pathways exist; health-care providers must rely on their own clinical judgment to manage these patients. This article provides practical recommendations—based on a framework of clinical, pharmacokinetic, and dosing considerations—to guide clinicians’ decisions regarding management of breakthrough psychotic symptoms. -

Drug-Induced Parkinsonism

InformationInformation Sheet Sheet Drug-induced Parkinsonism Terms highlighted in bold italic are defined in increases with age, hypertension, diabetes, the glossary at the end of this information sheet. atrial fibrillation, smoking and high cholesterol), because of an increased risk of stroke and What is drug-induced parkinsonism? other cerebrovascular problems. It is unclear About 7% of people with parkinsonism whether there is an increased risk of stroke with have developed their symptoms following quetiapine and clozapine. See the Parkinson’s treatment with particular medications. This UK information sheet Hallucinations and form of parkinsonism is called ‘drug-induced Parkinson’s. parkinsonism’. While these drugs are used primarily as People with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease antipsychotic agents, it is important to note and other causes of parkinsonism may also that they can be used for other non-psychiatric develop worsening symptoms if treated with uses, such as control of nausea and vomiting. such medication inadvertently. For people with Parkinson’s, other anti-sickness drugs such as domperidone (Motilium) or What drugs cause drug-induced ondansetron (Zofran) would be preferable. parkinsonism? Any drug that blocks the action of dopamine As well as neuroleptics, some other drugs (referred to as a dopamine antagonist) is likely can cause drug-induced parkinsonism. to cause parkinsonism. Drugs used to treat These include some older drugs used to treat schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders high blood pressure such as methyldopa such as behaviour disturbances in people (Aldomet); medications for dizziness and with dementia (known as neuroleptic drugs) nausea such as prochlorperazine (Stemetil); are possibly the major cause of drug-induced and metoclopromide (Maxolon), which is parkinsonism worldwide. -

Drug Calculations in Schizophrenia the National Institute for Health And

Calculations for injectable and oral drugs in schizophrenia Item Type Article Authors Khan, Nahim Citation Calculations for injectable and oral drugs in schizophrenia 2015, 13 (5):217 Nurse Prescribing DOI 10.12968/npre.2015.13.5.217 Journal Nurse Prescribing Rights Archived with thanks to Nurse Prescribing Download date 01/10/2021 04:03:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/579377 Drug Calculations in Schizophrenia The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the use of medication for the acute management of disturbed and violent behaviour (2005). NICE recommends firstly de-escalation and environmental techniques before utilising medication. Benzodiazepines can be used for their anxiolyic effects but antipsychotics can also be used as they can cause sedation and NICE suggests their use when there is a psychotic context to the unsettled behaviour. A patient is admitted who is acutely psychotic and is very unsettled. If de-escalation attempts fail and his behaviour continues to be dangerous to himself or to others; it is decided to prescribe haloperidol and lorazepam both orally and, when offered and not accepted, intra-muscularly (IM). The manufacturer of lorazepam injection states that before administration, it should be diluted 1:1 with normal saline or water for injection (Pfizer, 2014). 1mg is prescribed as required with a maximum of 4mg in 24hrs. The injection is available 4mg/ml ampoules. (a) How much mL should be injected to administer 1mg? (b) How much water for injection should be used to be used to dilute the lorazepam? Haloperidol 5mg/5mL IM injection has a maximum daily dose of 12mg and oral haloperidol has a maximum daily 20mg daily (Joint Formulary Committee, 2014).