3. Previous Archaeological Research at Mt Eburru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explanations of Variability in Middle Stone Age Stone Tool Assemblage Composition and Raw Material Use in Eastern Africa

Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2021) 13:14 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-020-01250-8 ORIGINAL PAPER Explanations of variability in Middle Stone Age stone tool assemblage composition and raw material use in Eastern Africa J. Blinkhorn1,2 & M. Grove3 Received: 26 February 2020 /Accepted: 1 December 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The Middle Stone Age (MSA) corresponds to a critical phase in human evolution, overlapping with the earliest emergence of Homo sapiens as well as the expansions of these populations across and beyond Africa. Within the context of growing recog- nition for a complex and structured population history across the continent, Eastern Africa remains a critical region to explore patterns of behavioural variability due to the large number of well-dated archaeological assemblages compared to other regions. Quantitative studies of the Eastern African MSA record have indicated patterns of behavioural variation across space, time and from different environmental contexts. Here, we examine the nature of these patterns through the use of matrix correlation statistics, exploring whether differences in assemblage composition and raw material use correlate to differences between one another, assemblage age, distance in space, and the geographic and environmental characteristics of the landscapes surrounding MSA sites. Assemblage composition and raw material use correlate most strongly with one another, with site type as well as geographic and environmental variables also identified as having significant correlations to the former, and distance in time and space correlating more strongly with the latter. By combining time and space into a single variable, we are able to show the strong relationship this has with differences in stone tool assemblage composition and raw material use, with significance for exploring the impacts of processes of cultural inheritance on variability in the MSA. -

1646 KMS Kenya Past and Present Issue 46.Pdf

Kenya Past and Present ISSUE 46, 2019 CONTENTS KMS HIGHLIGHTS, 2018 3 Pat Jentz NMK HIGHLIGHTS, 2018 7 Juliana Jebet NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS 13 AT MT. ELGON CAVES, WESTERN KENYA Emmanuel K. Ndiema, Purity Kiura, Rahab Kinyanjui RAS SERANI: AN HISTORICAL COMPLEX 22 Hans-Martin Sommer COCKATOOS AND CROCODILES: 32 SEARCHING FOR WORDS OF AUSTRONESIAN ORIGIN IN SWAHILI Martin Walsh PURI, PAROTHA, PICKLES AND PAPADAM 41 Saryoo Shah ZANZIBAR PLATES: MAASTRICHT AND OTHER PLATES 45 ON THE EAST AFRICAN COAST Villoo Nowrojee and Pheroze Nowrojee EXCEPTIONAL OBJECTS FROM KENYA’S 53 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES Angela W. Kabiru FRONT COVER ‘They speak to us of warm welcomes and traditional hospitality, of large offerings of richly flavoured rice, of meat cooked in coconut milk, of sweets as generous in quantity as the meals they followed.’ See Villoo and Pheroze Nowrojee. ‘Zanzibar Plates’ p. 45 1 KMS COUNCIL 2018 - 2019 KENYA MUSEUM SOCIETY Officers The Kenya Museum Society (KMS) is a non-profit Chairperson Pat Jentz members’ organisation formed in 1971 to support Vice Chairperson Jill Ghai and promote the work of the National Museums of Honorary Secretary Dr Marla Stone Kenya (NMK). You are invited to join the Society and Honorary Treasurer Peter Brice receive Kenya Past and Present. Privileges to members include regular newsletters, free entrance to all Council Members national museums, prehistoric sites and monuments PR and Marketing Coordinator Kari Mutu under the jurisdiction of the National Museums of Weekend Outings Coordinator Narinder Heyer Kenya, entry to the Oloolua Nature Trail at half price Day Outings Coordinator Catalina Osorio and 5% discount on books in the KMS shop. -

Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72

8/27/2021 Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72 https://haplogroup.info/ Object‐ID Colloquial‐Skeletal LatitudLongit Sex mtDNA‐comtFARmtDNA‐haplogroup mtDNA‐Haplotree mt‐FT mtree mt‐YFFTDNA‐mt‐Haplotree mt‐Simmt‐S HVS‐I HVS‐II HVS‐NO mt‐SNPs Responsible‐ Y‐DNA Y‐New SNP‐positive SNP‐negative SNP‐dubious NRY Y‐FARY‐Simple YTree Y‐Haplotree‐VY‐Haplotree‐PY‐FTD YFull Y‐YFu ISOGG2019 FTDNA‐Y‐Haplotree Y‐SymY‐Symbol2Responsible‐SNPSNPs AutosomaDamage‐RAssessmenKinship‐Notes Source Method‐Date Date Mean CalBC_top CalBC_bot Age Simplified_Culture Culture_Grouping Label Location SiteID Country Denisova4 FR695060.1 51.4 84.7 M DN1a1 DN1a1 https:/ROOT>HD>DN1>D1a>D1a1 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 708,133.1 (549,422.5‐930,979.7) A0000 A0000 A0000 A0000 A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 84.1–55.2 ka [Douka ‐67700 ‐82150 ‐53250 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Denisova8 KT780370.1 51.4 84.7 M DN2 DN2 https:/ROOT>HD>DN2 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 706,874.9 (607,187.2‐833,211.4) A0000 A0000‐T A0000‐T A0000‐T A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 136.4–105.6 ka ‐119050 ‐134450 ‐103650 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Spy_final Spy 94a 50.5 4.67 .. ND1b1a1b2* ND1b1a1b2* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a>ND1b1a1>ND1b1a1b>ND1b1a1b2 ND L C6563T * A11YFull TMRCA ca. 369,637.7 (326,137.1‐419,311.0) A000 A000a A000a A000‐T>A000>A000a A0 A000 PetrbioRxiv2020 553719 0.66381 .. PASS (literan/a HajdinjakNature2018 from MeyDirect: 95.4%; IntCal20, OxC39431‐38495 calBCE ‐38972 ‐39431 ‐38495 Neanderthal Late Middle Palaeolithic Spy_Neanderthal.SG Grotte de Spy, Jemeppe‐sur‐Sambre, Namur Belgium El Sidron 1253 FM865409.1 43.4 ‐5.33 ND1b1a* ND1b1a* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a ND L YFull TMRCA ca. -

Kenyan Stone Age: the Louis Leakey Collection

World Archaeology at the Pitt Rivers Museum: A Characterization edited by Dan Hicks and Alice Stevenson, Archaeopress 2013, pages 35-21 3 Kenyan Stone Age: the Louis Leakey Collection Ceri Shipton Access 3.1 Introduction Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey is considered to be the founding father of palaeoanthropology, and his donation of some 6,747 artefacts from several Kenyan sites to the Pitt Rivers Museum (PRM) make his one of the largest collections in the Museum. Leakey was passionate aboutopen human evolution and Africa, and was able to prove that the deep roots of human ancestry lay in his native east Africa. At Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania he excavated an extraordinary sequence of Pleistocene human evolution, discovering several hominin species and naming the earliest known human culture: the Oldowan. At Olorgesailie, Kenya, he excavated an Acheulean site that is still influential in our understanding of Lower Pleistocene human behaviour. On Rusinga Island in Lake Victoria, Kenya he found the Miocene ape ancestor Proconsul. He obtained funding to establish three of the most influential primatologists in their field, dubbed Leakey’s ‘ape women’; Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Birute Galdikas, who pioneered the study of chimpanzee, gorilla and orangutan behaviour respectively. His second wife Mary Leakey, whom he first hired as an artefact illustrator, went on to be a great researcher in her own right, surpassing Louis’ work with her own excavations at Olduvai Gorge. Mary and Louis’ son Richard followed his parents’ career path initially, discovering many of the most important hominin fossils including KNM WT 15000 (the Nariokotome boy, a near complete Homo ergaster skeleton), KNM WT 17000 (the type specimen for Paranthropus aethiopicus), and KNM ER 1470 (the type specimen for Homo rudolfensis with an extremely well preserved Archaeopressendocranium). -

COVID Fight Gets a Boost, US Backs Vaccine Patent Waiver See Page 10 2 Friday Local Friday, May 7, 2021

FREE Established 1961 Friday ISSUE NO: 18429 RAMADAN 25, 1442 AH FRIDAY, MAY 7, 2021 Fajr 03:34 Shurooq 05:02 Dhuhr 11:45 Asr 15:20 Maghrib 18:28 Isha 19:53 COVID fight gets a boost, US backs vaccine patent waiver See Page 10 2 Friday Local Friday, May 7, 2021 PHOTO OF THE DAY Colorful tassels hanging at a shop in Souq Al-Mubarakiya. — Photo by Yasser Al-Zayyat The Other Virus and its Variant our minds. We stop trusting experts or anyone, for that in a pandemic, let us repeat, it is fatal. It is understandable IN MY VIEW matter. We deny everything unless it comes from our own to be afraid. The whole world has been shaken by this virus. mind. And we self-appoint our mind as intelligent, aware, But for us to tell people the virus is not that dangerous or, and the main source of all our information-even though FNI at worst, doesn’t exist, or that the vaccine is unnecessary is By Nejoud Al-Yagout and COI both originate in the mind. What results is that all downright cruel. To tell people that if they take the vaccine reason has been taken over and we become vulnerable to they will become hypnotized by the government and killed [email protected] misinformation. What’s worse is not only that these two off, one by one, is more dangerous than Covid itself. To be viruses are contagious, but those struck by any of the two an anti-vaxxer is anyone’s right. -

Preliminary Results from Kenya

This article was downloaded by: [the Bodleian Libraries of the University of Oxford] On: 18 May 2012, At: 08:46 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raza20 Exploring agriculture, interaction and trade on the eastern African littoral: preliminary results from Kenya Richard Helm a , Alison Crowther b , Ceri Shipton c , Amini Tengeza d , Dorian Fuller e & Nicole Boivin b a Canterbury Archaeological Trust, 92a Broad Street, Canterbury, CT1 2LU, United Kingdom b Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3QY, United Kingdom c School of Social Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, 4072, Australia d Coastal Forest Conservation Unit, National Museums of Kenya, PO Box 596, Kilifi, Kenya e Institute of Archaeology, University College London, 31–34 Gordon Square, London, WC1H 0PY, United Kingdom Available online: 27 Feb 2012 To cite this article: Richard Helm, Alison Crowther, Ceri Shipton, Amini Tengeza, Dorian Fuller & Nicole Boivin (2012): Exploring agriculture, interaction and trade on the eastern African littoral: preliminary results from Kenya, Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 47:1, 39-63 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2011.647947 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. -

Preliminary Visual Survey of Several Sites of Potential Archaeological Interest at Ol Ari Nyiro Ranch, Laikipia Nature Conservancy, the Gallmann Memorial Foundation

PRELIMINARY VISUAL SURVEY OF SEVERAL SITES OF POTENTIAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTEREST AT OL ARI NYIRO RANCH, LAIKIPIA NATURE CONSERVANCY, THE GALLMANN MEMORIAL FOUNDATION OL ARI NYIRO ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT GALLMANN MEMORIAL FOUNDATION Ana C. Pinto LLona, MA, PhD Instituto de Historia Departamento de Prehistoria Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas c/ Duque de Medinaceli, 8 28014 Madrid, Spain Laikipia, Kenya, August 2006 INDEX Acknowledgements pg. 3 Methods for a Survey of Archaeological Sites and Potencial at Ol Ari Nyiro pg. 4 Some feedback: What is the Stone age? pg. 5 I.- Introduction II.- Study of the Stone Age pg. 5 General Concepts Human Evolution Geologic Epochs of the Stone Age Stone Age Toolmaking Technology III.- Divisions of the Stone Age pg. 7 Palaeolithic Lower Palaeolithic Oldowan Industry Acheulean Industry Middle Palaeolithic/African Middle Stone Age Innovations of the Middle Paleolithic/MSA Middle Palaeolithic/MSA Humans Upper Palaeolithic/African Later Stone Age Innovations of the Upper Palaeolithic/LSA Upper Palaeolithic Culture Upper Palaeolithic Art Mesolithic or Epipaleolithic Neolithic The Rise of Farming Neolithic Social Change IV.- The End of the Stone Age pg. 18 V.- Some Archaeological Sites in Kenya pg. 19 VI.- Some Sites of Archaeological relevance at Ol Ari Nyiro pg. 21 Sambara Caves A and B pg. 21 Jangili Cave pg. 23 Iron Smelting Sites A and B pg. 25 Iron Age Settlement Bogani ya Dume ya Juu pg. 28 Iron Age Settlement Mlima Undongo near Ochre Hill pg. 31 Megaliths pg. 31 Red Ochre Hill and Obsidian Plan pg. 35 A New Homo erectus Site: Poromoko VII. Annexes Things a surveyor needs… UTM locations of sites surveyed Inventory of Surface Acheulean Tools from Poromoko Ol Ari Nyiro Archaeological Project Anatomical Collection of Reference: Inventory of collected remains of Felis panthera leo 2 Acknowledgements I have received the help and collaboration of many individuals during my time at Ol Ari Nyiro, and each one has been of value. -

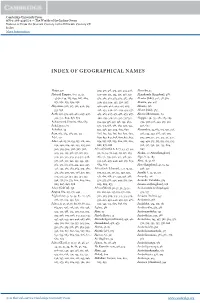

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

Subsistence Mosaics, Forager-Farmer Interactions, and the Transition to Food Production in Eastern Africa

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e20 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Subsistence mosaics, forager-farmer interactions, and the transition to food production in eastern Africa * Alison Crowther a, , Mary E. Prendergast b, Dorian Q. Fuller c, Nicole Boivin d a School of Social Science, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, 4072, Australia b Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 02138, USA c Institute of Archaeology, University College London, London, WC1H 0PY, United Kingdom d Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, 07745, Germany article info abstract Article history: The spread of agriculture across sub-Saharan Africa has long been attributed to the large-scale migration Received 16 March 2016 of Bantu-speaking groups out of their west Central African homeland from about 4000 years ago. These Received in revised form groups are seen as having expanded rapidly across the sub-continent, carrying an ‘Iron Age’ package of 8 December 2016 farming, metal-working, and pottery, and largely replacing pre-existing hunter-gatherers along the way. Accepted 13 January 2017 While elements of the ‘traditional’ Bantu model have been deconstructed in recent years, one of the main Available online xxx constraints on developing a more nuanced understanding of the local processes involved in the spread of farming has been the lack of detailed archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological sequences, particularly Keywords: Bantu expansion from key regions such as eastern Africa. Situated at a crossroads between continental Africa and the Iron age Indian Ocean, eastern Africa was not only a major corridor on one of the proposed Bantu routes to Pastoralism southern Africa, but also the recipient of several migrations of pastoral groups from the north. -

Program of the 79Th Annual Meeting

Program of the 79th Annual Meeting April 23–27, 2014 Austin, Texas THE ANNUAL MEETING of the Society for American Archaeology provides a fo- rum for the dissemination of knowledge and discussion. The views expressed at the sessions are solely those of the speakers and the Society does not endorse, approve, or censor them. Descriptions of events and titles are those of the orga- nizers, not the Society. Program of the 79th Annual Meeting Published by the Society for American Archaeology 1111 14th Street NW, Suite 800 Washington DC 20005 5622 USA Tel: +1 202/789 8200 Fax: +1 202/789 0284 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.saa.org Copyright © 2014 Society for American Archaeology. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher. Contents 4 Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting Agenda 5 2014 Award Recipients 12 Maps 17 Meeting Organizers, SAA Board of Directors, & SAA Staff 19 General Information 21 Featured Sessions 23 Summary Schedule 27 A Word about the Sessions 28 Student Day 2014 29 Sessions At A Glance 37 Program 214 SAA Awards, Scholarships, & Fellowships 222 Presidents of SAA 222 Annual Meeting Sites 224 Exhibit Map 225 Exhibitor Directory 236 SAA Committees and Task Forces 241 Index of Participants 4 Program of the 79th Annual Meeting Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting April 25, 2014 5 PM Call to Order Call for Approval of Minutes of the 2013 Annual Business Meeting Remarks President Jeffrey H. Altschul Reports Treasurer Alex W. Barker Secretary Christina B. -

Swahili Forum 10 (2003)

SSWWAAHHIILLII FFOORRUUMM 1100 Edited by Rose Marie Beck, Lutz Diegner, Thomas Geider, Uta Reuster-Jahn 2003 Department of Anthropology and African Studies Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Germany Swahili Forum 10 (2003) A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SWAHILI LITERATURE, LINGUISTICS, CULTURE AND HISTORY Compiled by Thomas Geider The present alphabetical Bibliography ranging from 'Abdalla' to 'Zhukov' includes old and new titles on Swahili Literature, Linguistics, Culture and History. Swahili Studies or 'Swahil- istics' have grown strong since the mid-1980s when scholars started to increasingly engage in international networking, first by communicating through the newsletter Swahili Language and Society: Notes and News from Vienna (Nos. 1.1984-9.1992) and Antwerp (No. 10.1993) and then through the journal Swahili Forum published at the University of Cologne (Nos. I. 1994 - IX. 2002), not to mention the numerous conferences held in Dar es Salaam, Nairobi, London, Bayreuth and other places, and not to forget the achievements of the journal Kiswa- hili from Dar es Salaam as another steady medium of Swahili scholarship. Part of this net- working consists of continuously updated bibliographical information which has been pro- vided in different forms: a coherent collection of bibliographical data was annually issued in the SLS: NN-Letters, based on regular submissions of correspondents. Swahili Forum was less successful in this as scholars only occasionally sent in information. So from No. VII onwards it was decided to include articles providing bibliographical data. These derived from subjec- tive scholarly interest of the author as well as from regular checking of the book and journal accessions in four major Africanist libraries in Germany (Geider 2000, 2001, 2002). -

The Middle to Later Stone Age Transition at Panga Ya Saidi, in the Tropical Coastal Forest Of

1 The Middle to Later Stone Age transition at Panga ya Saidi, in the tropical coastal forest of 2 eastern Africa 3 4 Abstract 5 The Middle to Later Stone Age transition is a critical period of human behavioral change that 6 has been variously argued to pertain to the emergence of modern cognition, substantial 7 population growth, and major dispersals of Homo sapiens within and beyond Africa. 8 However, there is little consensus about when the transition occurred, the geographic 9 patterning of its emergence, or even how it is manifested in stone tool technology that is used 10 to define it. Here we examine a long sequence of lithic technological change at the cave site 11 of Panga ya Saidi, Kenya, that spans the Middle and Later Stone Age and includes human 12 occupations in each of the last five Marine Isotope Stages. In addition to the stone artifact 13 technology, Panga ya Saidi preserves osseous and shell artifacts enabling broader 14 considerations of the covariation between different spheres of material culture. Several 15 environmental proxies contextualize the artifactual record of human behavior at Panga ya 16 Saidi. We compare technological change between the Middle and Later Stone Age to on-site 17 paleoenvironmental manifestations of wider climatic fluctuations in the Late Pleistocene. The 18 principal distinguishing feature of Middle from Later Stone Age technology at Panga ya Saidi 19 is the preference for fine-grained stone, coupled with the creation of small flakes 20 (miniaturization). Our review of the Middle to Later Stone Age transition elsewhere in 21 eastern Africa and across the continent suggests that this broader distinction between the two 22 periods is in fact widespread.