Science Journals — AAAS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72

8/27/2021 Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72 https://haplogroup.info/ Object‐ID Colloquial‐Skeletal LatitudLongit Sex mtDNA‐comtFARmtDNA‐haplogroup mtDNA‐Haplotree mt‐FT mtree mt‐YFFTDNA‐mt‐Haplotree mt‐Simmt‐S HVS‐I HVS‐II HVS‐NO mt‐SNPs Responsible‐ Y‐DNA Y‐New SNP‐positive SNP‐negative SNP‐dubious NRY Y‐FARY‐Simple YTree Y‐Haplotree‐VY‐Haplotree‐PY‐FTD YFull Y‐YFu ISOGG2019 FTDNA‐Y‐Haplotree Y‐SymY‐Symbol2Responsible‐SNPSNPs AutosomaDamage‐RAssessmenKinship‐Notes Source Method‐Date Date Mean CalBC_top CalBC_bot Age Simplified_Culture Culture_Grouping Label Location SiteID Country Denisova4 FR695060.1 51.4 84.7 M DN1a1 DN1a1 https:/ROOT>HD>DN1>D1a>D1a1 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 708,133.1 (549,422.5‐930,979.7) A0000 A0000 A0000 A0000 A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 84.1–55.2 ka [Douka ‐67700 ‐82150 ‐53250 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Denisova8 KT780370.1 51.4 84.7 M DN2 DN2 https:/ROOT>HD>DN2 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 706,874.9 (607,187.2‐833,211.4) A0000 A0000‐T A0000‐T A0000‐T A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 136.4–105.6 ka ‐119050 ‐134450 ‐103650 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Spy_final Spy 94a 50.5 4.67 .. ND1b1a1b2* ND1b1a1b2* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a>ND1b1a1>ND1b1a1b>ND1b1a1b2 ND L C6563T * A11YFull TMRCA ca. 369,637.7 (326,137.1‐419,311.0) A000 A000a A000a A000‐T>A000>A000a A0 A000 PetrbioRxiv2020 553719 0.66381 .. PASS (literan/a HajdinjakNature2018 from MeyDirect: 95.4%; IntCal20, OxC39431‐38495 calBCE ‐38972 ‐39431 ‐38495 Neanderthal Late Middle Palaeolithic Spy_Neanderthal.SG Grotte de Spy, Jemeppe‐sur‐Sambre, Namur Belgium El Sidron 1253 FM865409.1 43.4 ‐5.33 ND1b1a* ND1b1a* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a ND L YFull TMRCA ca. -

COVID Fight Gets a Boost, US Backs Vaccine Patent Waiver See Page 10 2 Friday Local Friday, May 7, 2021

FREE Established 1961 Friday ISSUE NO: 18429 RAMADAN 25, 1442 AH FRIDAY, MAY 7, 2021 Fajr 03:34 Shurooq 05:02 Dhuhr 11:45 Asr 15:20 Maghrib 18:28 Isha 19:53 COVID fight gets a boost, US backs vaccine patent waiver See Page 10 2 Friday Local Friday, May 7, 2021 PHOTO OF THE DAY Colorful tassels hanging at a shop in Souq Al-Mubarakiya. — Photo by Yasser Al-Zayyat The Other Virus and its Variant our minds. We stop trusting experts or anyone, for that in a pandemic, let us repeat, it is fatal. It is understandable IN MY VIEW matter. We deny everything unless it comes from our own to be afraid. The whole world has been shaken by this virus. mind. And we self-appoint our mind as intelligent, aware, But for us to tell people the virus is not that dangerous or, and the main source of all our information-even though FNI at worst, doesn’t exist, or that the vaccine is unnecessary is By Nejoud Al-Yagout and COI both originate in the mind. What results is that all downright cruel. To tell people that if they take the vaccine reason has been taken over and we become vulnerable to they will become hypnotized by the government and killed [email protected] misinformation. What’s worse is not only that these two off, one by one, is more dangerous than Covid itself. To be viruses are contagious, but those struck by any of the two an anti-vaxxer is anyone’s right. -

Preliminary Results from Kenya

This article was downloaded by: [the Bodleian Libraries of the University of Oxford] On: 18 May 2012, At: 08:46 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raza20 Exploring agriculture, interaction and trade on the eastern African littoral: preliminary results from Kenya Richard Helm a , Alison Crowther b , Ceri Shipton c , Amini Tengeza d , Dorian Fuller e & Nicole Boivin b a Canterbury Archaeological Trust, 92a Broad Street, Canterbury, CT1 2LU, United Kingdom b Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3QY, United Kingdom c School of Social Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, 4072, Australia d Coastal Forest Conservation Unit, National Museums of Kenya, PO Box 596, Kilifi, Kenya e Institute of Archaeology, University College London, 31–34 Gordon Square, London, WC1H 0PY, United Kingdom Available online: 27 Feb 2012 To cite this article: Richard Helm, Alison Crowther, Ceri Shipton, Amini Tengeza, Dorian Fuller & Nicole Boivin (2012): Exploring agriculture, interaction and trade on the eastern African littoral: preliminary results from Kenya, Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 47:1, 39-63 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2011.647947 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. -

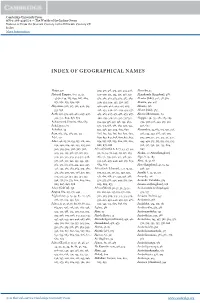

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

Subsistence Mosaics, Forager-Farmer Interactions, and the Transition to Food Production in Eastern Africa

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e20 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Subsistence mosaics, forager-farmer interactions, and the transition to food production in eastern Africa * Alison Crowther a, , Mary E. Prendergast b, Dorian Q. Fuller c, Nicole Boivin d a School of Social Science, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, 4072, Australia b Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 02138, USA c Institute of Archaeology, University College London, London, WC1H 0PY, United Kingdom d Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, 07745, Germany article info abstract Article history: The spread of agriculture across sub-Saharan Africa has long been attributed to the large-scale migration Received 16 March 2016 of Bantu-speaking groups out of their west Central African homeland from about 4000 years ago. These Received in revised form groups are seen as having expanded rapidly across the sub-continent, carrying an ‘Iron Age’ package of 8 December 2016 farming, metal-working, and pottery, and largely replacing pre-existing hunter-gatherers along the way. Accepted 13 January 2017 While elements of the ‘traditional’ Bantu model have been deconstructed in recent years, one of the main Available online xxx constraints on developing a more nuanced understanding of the local processes involved in the spread of farming has been the lack of detailed archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological sequences, particularly Keywords: Bantu expansion from key regions such as eastern Africa. Situated at a crossroads between continental Africa and the Iron age Indian Ocean, eastern Africa was not only a major corridor on one of the proposed Bantu routes to Pastoralism southern Africa, but also the recipient of several migrations of pastoral groups from the north. -

Swahili Forum 10 (2003)

SSWWAAHHIILLII FFOORRUUMM 1100 Edited by Rose Marie Beck, Lutz Diegner, Thomas Geider, Uta Reuster-Jahn 2003 Department of Anthropology and African Studies Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Germany Swahili Forum 10 (2003) A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SWAHILI LITERATURE, LINGUISTICS, CULTURE AND HISTORY Compiled by Thomas Geider The present alphabetical Bibliography ranging from 'Abdalla' to 'Zhukov' includes old and new titles on Swahili Literature, Linguistics, Culture and History. Swahili Studies or 'Swahil- istics' have grown strong since the mid-1980s when scholars started to increasingly engage in international networking, first by communicating through the newsletter Swahili Language and Society: Notes and News from Vienna (Nos. 1.1984-9.1992) and Antwerp (No. 10.1993) and then through the journal Swahili Forum published at the University of Cologne (Nos. I. 1994 - IX. 2002), not to mention the numerous conferences held in Dar es Salaam, Nairobi, London, Bayreuth and other places, and not to forget the achievements of the journal Kiswa- hili from Dar es Salaam as another steady medium of Swahili scholarship. Part of this net- working consists of continuously updated bibliographical information which has been pro- vided in different forms: a coherent collection of bibliographical data was annually issued in the SLS: NN-Letters, based on regular submissions of correspondents. Swahili Forum was less successful in this as scholars only occasionally sent in information. So from No. VII onwards it was decided to include articles providing bibliographical data. These derived from subjec- tive scholarly interest of the author as well as from regular checking of the book and journal accessions in four major Africanist libraries in Germany (Geider 2000, 2001, 2002). -

The Middle to Later Stone Age Transition at Panga Ya Saidi, in the Tropical Coastal Forest Of

1 The Middle to Later Stone Age transition at Panga ya Saidi, in the tropical coastal forest of 2 eastern Africa 3 4 Abstract 5 The Middle to Later Stone Age transition is a critical period of human behavioral change that 6 has been variously argued to pertain to the emergence of modern cognition, substantial 7 population growth, and major dispersals of Homo sapiens within and beyond Africa. 8 However, there is little consensus about when the transition occurred, the geographic 9 patterning of its emergence, or even how it is manifested in stone tool technology that is used 10 to define it. Here we examine a long sequence of lithic technological change at the cave site 11 of Panga ya Saidi, Kenya, that spans the Middle and Later Stone Age and includes human 12 occupations in each of the last five Marine Isotope Stages. In addition to the stone artifact 13 technology, Panga ya Saidi preserves osseous and shell artifacts enabling broader 14 considerations of the covariation between different spheres of material culture. Several 15 environmental proxies contextualize the artifactual record of human behavior at Panga ya 16 Saidi. We compare technological change between the Middle and Later Stone Age to on-site 17 paleoenvironmental manifestations of wider climatic fluctuations in the Late Pleistocene. The 18 principal distinguishing feature of Middle from Later Stone Age technology at Panga ya Saidi 19 is the preference for fine-grained stone, coupled with the creation of small flakes 20 (miniaturization). Our review of the Middle to Later Stone Age transition elsewhere in 21 eastern Africa and across the continent suggests that this broader distinction between the two 22 periods is in fact widespread. -

Spatial Distribution and Settlement Systems: a Case Study of the South Western Kenya Stone Structures

4- SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION AND SETTLEMENT SYSTEMS: A CASE STUDY OF THE SOUTH WESTERN KENYA STONE STRUCTURES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI. BY ISAYA O. ONJALA 1994 UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI LIBRARY A Case Study of the South Western Kenya Stone Structures u DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for any degree in any University. Isaya O. Onjala This thesis has been submitted for examination with ou£ approval as University Supervisors 1. Prof. C.M. Nelson Signature 2. Dr. H.W. Mutoro Signature A Case Study of the South Western Kenya Stone Structures in CONTENTS Declaration........................................................................................................................................... ii Table of contents.......................................................................... ....................................................... ii.i. List of Tables........................................................................................................................................iv List of Figures......................................................................................................................................Y Abstract.............................................................................................................................................. YJ Acknowledgments.............................................................................................................................Yii -

1 the Structure of the Middle Stone Age of Eastern Africa 1

1 The structure of the Middle Stone Age of eastern Africa 2 Blinkhorn, J.1,2 & Grove, M.3 3 1 – Department of Geography, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey, UK 4 2 – Department of Archaeology, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, 5 Germany 6 3 – Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool, 12-14 7 Abercromby Square, Liverpool, UK 8 Abstract: 9 The Middle Stone Age (MSA) of eastern Africa has a long history of research and is 10 accompanied by a rich fossil record, which, combined with its geographic location, have led it 11 to play an important role in investigating the origins and expansions of Homo sapiens. Recent 12 evidence has suggested an earlier appearance of our species, indicating a more mosaic origin 13 of modern humans, highlighting the importance of regional and inter-regional patterning and 14 bringing into question the role that eastern Africa has played. Previous evaluations of the 15 eastern African MSA have identified substantial variability, only a small proportion of which is 16 explained by chronology and geography. Here, we examine the structure of behavioural, 17 temporal, geographic and environmental variability within and between sites across eastern 18 Africa using a quantitative approach. The application of hierarchical clustering identifies 19 enduring patterns of tool use and site location through the MSA as well as phases of significant 20 behavioural diversification and colonisation of new landscapes, particularly notable during 21 Marine Isotope Stage 5. As the quantity and detail of technological studies from individual 1 22 sites in eastern Africa gathers pace, the structure of the MSA record highlighted here offers a 23 roadmap for comparative studies. -

An Annotated Bibliography Africa

RESEARCHING THE WORLD’S BEADS: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by Karlis Karklins Society of Bead Researchers Revised and Updated 1 July 2021 AFRICA This section of the bibliography encompasses the entire continent of Africa with the exception of Egypt which is included in the Middle East. Also included are islands off the east and west coast of Africa such as St. Helena and the Canary Islands. See also the two specialized theme bibliographies and the General and Miscellaneous bibliography as they also contain reports dealing with these countries. Abungu, L. 1992 Beads on the East African Coast: An Outline. In Urban Origins in Eastern Africa: Proceedings of the 1991 Workshop in Zanzibar, edited by P.J.J. Sinclair and A. Juma, pp. 100-106. The Swedish Central Board of National Antiquities, Stockholm. Adeduntan, J. 1985 Early Glass Bead Technology of Ile-Ife. West African Journal of Archaeology 15:165- 171. Nineteen whole beads and twenty-eight fragments were collected from the Ayelabowo site near Ile-Ife, Nigeria. The beads are discussed insofar as they serve as a basis for reconstructing and dating glass bead technology at Ile-Ife. Agorsah, E. Kofi 1994 Before the Flood: The Golden Volta Basin. Nyame Akuma 41:25-36. Excavations at Kononaye, Ghana, produced 15th-century glass beads. Ajetunmobi, R.O. 1989 The Origin, Development and Decline of Glass Bead Industry in Ile-Ife. M.A. thesis. Department of History, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. 2000 Decline of the Glass Bead Industry in Ile-Ife: A Historical Discourse. Journal of Arts and Social Sciences. -

National Assembly

March 12, 2019 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES 1 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL REPORT Tuesday, 12th March 2019 The House met at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Justin Muturi) in the Chair] PRAYERS PETITION AMENDING THE CONSTITUTION TO ALTER THE SYSTEM OF REPRESENTATION OF THE PEOPLE Hon. Speaker: Hon. Members, this is Public Petition No.20 of 2019. Standing Order No. 225(2)(b) requires the Speaker to report to the House any petition, other than those presented through a Member. I would like to convey to the House that my office has received a petition submitted by one, Mr. Julius Kipkoech Bores, requesting that Parliament, pursuant to Articles 93, 94 and 95 of the Constitution considers amending the Constitution of Kenya to alter the system of representation of the people. Hon. Members, the citizen has submitted the public petition in exercise of his “right to petition Parliament to consider any matter within its authority, including enacting, amending or repealing any legislation”. Petitioner, Mr. Julius Kipkoech Bores proposes that this House considers several amendments to the Constitution affecting the bicameral nature of the legislature, the two-thirds gender principle, among other proposals. Hon. Members, pursuant to the provisions of Standing Order 227, this Petition therefore stands committed to the Departmental Committee on Justice and Legal Affairs. The Committee is requested to consider the Petition and report its findings to the House and the petitioner in accordance with Standing Order 227(2). Thank you. Do Members who are on intervention want to comment on the Petition? Hon. Members: No. Hon. Speaker: The Petition is accordingly committed. -

Testing the Integrity of the Middle and Later Stone Age Cultural Taxonomic Division in Eastern Africa

Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-021-00087-4 Testing the Integrity of the Middle and Later Stone Age Cultural Taxonomic Division in Eastern Africa Matt Grove1 & James Blinkhorn2,3 Accepted: 1 February 2021/ # The Author(s) 2021 Abstract The long-standing debate concerning the integrity of the cultural taxonomies employed by archaeologists has recently been revived by renewed theoretical attention and the application of new methodological tools. The analyses presented here test the integrity of the cultural taxonomic division between Middle and Later Stone Age assemblages in eastern Africa using an extensive dataset of archaeological assemblages. Application of a penalized logistic regression procedure embedded within a permutation test allows for evaluation of the existing Middle and Later Stone Age division against numerous alternative divisions of the data. Results suggest that the existing division is valid based on any routinely employed statistical criterion, but that is not the single best division of the data. These results invite questions about what archaeologists seek to achieve via cultural taxonomy and about the analytical methods that should be employed when attempting revise existing nomenclature. Keywords Middle Stone Age . Later Stone Age . Cultural taxonomy . Lithic technology . Logistic regression . Permutation analysis This article belongs to the Topical Collection: Cultural taxonomies in the Palaeolithic - old questions, novel perspectives Guest Editors: Felix Riede and Shumon T. Hussain