Quaternary International 489 (2018) 101E120

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Burundi

Report No: ACS14147 . Public Disclosure Authorized Republic of Burundi Strategies for Urbanization and Public Disclosure Authorized Economic Competitiveness in Burundi . June 19, 2015 . GSURR Public Disclosure Authorized AFRICA . Public Disclosure Authorized Strategies for Urbanization and Economic Competitiveness in Burundi Standard Disclaimer: . This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: . The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

FARMERS in the Driver's Seat

FARMERS IN THE FARMERS FARMERS IN THE Properly functioning farmer organizations are essential to enable smallholder agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa to become more productive and profitable. Farmer organizations allow for collective action by smallholders, creating economies of scale, reducing transaction costs and thereby improving access to driver’s seaT markets. In order to sustain income generation through marketing of agricultural products, farmers and their organizations need to maintain their competitiveness and hence reinforce their capacity to innovate. driver’s seaT Innovation in smallholder agriculture in Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya and Rwanda The Association for Strengthening Agricultural Research in Eastern and Central Africa (ASARECA), through its Knowledge Management and Up-Scaling (KMUS) programme, initiated the ‘farmer empowerment for innovation in smallholder agriculture’ (FEISA) project (2010-2013). The project aimed to empower smallholder farmers in Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya and Rwanda to improve their productivity in selected value chains. The project put farmers in the driver’s seat by providing farmer organizations with tools and skills to enhance collaboration with private enterprises, as well as service providers, in multi-stakeholder ‘inno- vation triangles’ within value chains for the benefit of smallholder farmers. Built around case studies from the four countries, this book presents the innova- tion triangle approach, as well as a self-assessment tool for service provision by apex farmer organizations to their members. Both the innovation processes followed, and the results obtained, provide valuable insights on the facilitation of multi-stakeholder platforms for farmer-led innovation in value chains. These insights particularly focus on the role of, and services provided by, apex and grassroots farmer organizations for enhanced market access. -

Burundi Landscape Analysis

Integrating Gender and Nutrition within Agricultural Extension Services Burundi Landscape Analysis Prepared by Nargiza Ludgate and S. Joyous Tata September 2015 1 © INGENAES This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. Users are free: • To share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work. (without participant contact information) • To remix — to adapt the work. Under the following conditions: • Attribution — users must attribute the work to the authors but not in any way that suggests that the authors endorse the user or the user’s use of the work. Technical editing and production by Nargiza Ludgate, Joyous Tata, and Katy Heinz This report was produced as part of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and US Government Feed the Future project “Integrating Gender and Nutrition within Extension and Advisory Services” (INGENAES). www.ingenaes.illinois.edu Leader with Associates Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-LA-14-00008. The report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through USAID. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. Burundi Landscape Analysis Working document Prepared by Nargiza S. Ludgate, University of Florida Joyous S. Tata, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Cover photo by Doug Satre 2015 Burundi Landscape Study - September 2015 Abbreviations AFR/SD Bureau for Africa/Office of Sustainable Development BFS Bureau for Food Security Burundi -

Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72

8/27/2021 Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72 https://haplogroup.info/ Object‐ID Colloquial‐Skeletal LatitudLongit Sex mtDNA‐comtFARmtDNA‐haplogroup mtDNA‐Haplotree mt‐FT mtree mt‐YFFTDNA‐mt‐Haplotree mt‐Simmt‐S HVS‐I HVS‐II HVS‐NO mt‐SNPs Responsible‐ Y‐DNA Y‐New SNP‐positive SNP‐negative SNP‐dubious NRY Y‐FARY‐Simple YTree Y‐Haplotree‐VY‐Haplotree‐PY‐FTD YFull Y‐YFu ISOGG2019 FTDNA‐Y‐Haplotree Y‐SymY‐Symbol2Responsible‐SNPSNPs AutosomaDamage‐RAssessmenKinship‐Notes Source Method‐Date Date Mean CalBC_top CalBC_bot Age Simplified_Culture Culture_Grouping Label Location SiteID Country Denisova4 FR695060.1 51.4 84.7 M DN1a1 DN1a1 https:/ROOT>HD>DN1>D1a>D1a1 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 708,133.1 (549,422.5‐930,979.7) A0000 A0000 A0000 A0000 A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 84.1–55.2 ka [Douka ‐67700 ‐82150 ‐53250 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Denisova8 KT780370.1 51.4 84.7 M DN2 DN2 https:/ROOT>HD>DN2 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 706,874.9 (607,187.2‐833,211.4) A0000 A0000‐T A0000‐T A0000‐T A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 136.4–105.6 ka ‐119050 ‐134450 ‐103650 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Spy_final Spy 94a 50.5 4.67 .. ND1b1a1b2* ND1b1a1b2* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a>ND1b1a1>ND1b1a1b>ND1b1a1b2 ND L C6563T * A11YFull TMRCA ca. 369,637.7 (326,137.1‐419,311.0) A000 A000a A000a A000‐T>A000>A000a A0 A000 PetrbioRxiv2020 553719 0.66381 .. PASS (literan/a HajdinjakNature2018 from MeyDirect: 95.4%; IntCal20, OxC39431‐38495 calBCE ‐38972 ‐39431 ‐38495 Neanderthal Late Middle Palaeolithic Spy_Neanderthal.SG Grotte de Spy, Jemeppe‐sur‐Sambre, Namur Belgium El Sidron 1253 FM865409.1 43.4 ‐5.33 ND1b1a* ND1b1a* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a ND L YFull TMRCA ca. -

Climate Proofing Agricultural Investments Under the National Program for Food Security and Rural Development in Imbo and Moso (PNSADR-IM)

Climate Proofing Agricultural investments under the National Program for Food Security and Rural Development in Imbo and Moso (PNSADR-IM) | Burundi IFAD 20 September 2019 Climate Proofing Agricultural investments under the National Project/Programme title: Program for Food Security and Rural Development in Imbo and Moso (PNSADR-IM) Country(ies): Burundi National Designated Ministry of Environment, Agriculture, and Breeding Authority(ies) (NDA): Africa Sustainability Centre (ASCENT), PNSADR-IM Project Executing Entities: Management Unit (PMU) Accredited Entity(ies) (AE): International Fund for Agricultural Development Date of first submission/ 7/16/2019 V.1 version number: Date of current submission/ 9/20/2019 V.2 version number A. Project / Programme Information (max. 1 page) ☒ Project ☒ Public sector A.2. Public or A.1. Project or programme A.3 RFP Not applicable private sector ☐ Programme ☐ Private sector Mitigation: Reduced emissions from: ☐ Energy access and power generation: 0% ☐ Low emission transport: 0% ☐ Buildings, cities and industries and appliances: 0% A.4. Indicate the result ☐ Forestry and land use: 0% areas for the project/programme Adaptation: Increased resilience of: ☒ Most vulnerable people and communities: 33.333% ☒ Health and well-being, and food and water security: 33.333% ☐ Infrastructure and built environment: 0% ☒ Ecosystem and ecosystem services: 33.333% A.5.1. Estimated mitigation impact (tCO2eq over project lifespan) A.5.2. Estimated adaptation impact 333,450 direct beneficiaries (number of direct beneficiaries) A.5. Impact potential A.5.3. Estimated adaptation impact 2,003,450 indirect beneficiaries (number of indirect beneficiaries) A.5.4. Estimated adaptation impact 20% of the country’s total population (% of total population) A.6. -

WP24 Scoping Paper Burundi

A Scoping Study on Burundi’s Agricultural Production in a Changing Climate and the Supporting Policies Alexis Ndayiragije Desire Mkezabahizi Jean Ndimubandi Francoise Kabogoye Bureau for Agricultural Consultancy Service KIPPRA Working Paper No. 24 2017 A scoping study on Burundi’s agricultural production KIPPRA in Brief The Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA) is an autonomous institute whose primary mission is to conduct public policy research leading to policy advice. KIPPRA’s mission is to produce consistently high-quality analysis of key issues of public policy and to contribute to the achievement of national long-term development objectives by positively infuencing the decision-making process. These goals are met through efective dissemination of recommendations resulting from analysis and by training policy analysts in the public sector. KIPPRA therefore produces a body of well-researched and documented information on public policy, and in the process assists in formulating long-term strategic perspectives. KIPPRA serves as a centralized source from which the Government and the private sector may obtain information and advice on public policy issues. UNECA in Brief Established by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) of the United Nations (UN) in 1958 as one of the UN’s fve regional commissions, ECA’s mandate is to promote the economic and social development of its member States, foster intra-regional integration, and promote international cooperation for Africa’s development. Made up of 54 member States, and playing a dual role as a regional arm of the UN and as a key component of the African institutional landscape, ECA is well positioned to make unique contributions to address the Continent’s development challenges. -

COVID Fight Gets a Boost, US Backs Vaccine Patent Waiver See Page 10 2 Friday Local Friday, May 7, 2021

FREE Established 1961 Friday ISSUE NO: 18429 RAMADAN 25, 1442 AH FRIDAY, MAY 7, 2021 Fajr 03:34 Shurooq 05:02 Dhuhr 11:45 Asr 15:20 Maghrib 18:28 Isha 19:53 COVID fight gets a boost, US backs vaccine patent waiver See Page 10 2 Friday Local Friday, May 7, 2021 PHOTO OF THE DAY Colorful tassels hanging at a shop in Souq Al-Mubarakiya. — Photo by Yasser Al-Zayyat The Other Virus and its Variant our minds. We stop trusting experts or anyone, for that in a pandemic, let us repeat, it is fatal. It is understandable IN MY VIEW matter. We deny everything unless it comes from our own to be afraid. The whole world has been shaken by this virus. mind. And we self-appoint our mind as intelligent, aware, But for us to tell people the virus is not that dangerous or, and the main source of all our information-even though FNI at worst, doesn’t exist, or that the vaccine is unnecessary is By Nejoud Al-Yagout and COI both originate in the mind. What results is that all downright cruel. To tell people that if they take the vaccine reason has been taken over and we become vulnerable to they will become hypnotized by the government and killed [email protected] misinformation. What’s worse is not only that these two off, one by one, is more dangerous than Covid itself. To be viruses are contagious, but those struck by any of the two an anti-vaxxer is anyone’s right. -

Burundi in the Agribusiness Global Value Chain: Skills for Private Sector Development

Burundi in the Agribusiness Global Value Chain: Skills for Private Sector Development Burundi in the Agribusiness Global Value Chain SKILLS FOR PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT Penny Bamber Ajmal Abdulsamad Gary Gereffi Contributing CGGC Researchers: Andrew Hull, Grace Muhimpundu and Thupten Norbu 1 Burundi in the Agribusiness Global Value Chain: Skills for Private Sector Development This report was prepared on behalf of the World Bank. It draws on primary information from field interviews in Burundi carried out in August-September 2013 and January-February 2014, as well as secondary information sources. Errors of fact or interpretation remain the exclusive responsibility of the authors. The opinions expressed in this report are not endorsed by the World Bank or the interviewees. The final version of this report will be available at www.cggc.duke.edu. Acknowledgements Duke CGGC would like to thank all of the interviewees, who gave generously of their time and expertise. Duke CGGC would also like to extend special thanks to the World Bank for their contributions to the development of this report. In particular gratitude is due to Cristina Santos, Senior Education Specialist, Reehana Rifat Raza, Senior Human Development Economist, Sajitha Bashir, Sector Manager, Education (Eastern and Southern Africa), and Ifeyinwa Onugha, Competitive Industries Practice – Financial and Private Sector Development, the World Bank Group, for their guidance and insightful comments on earlier drafts. Duke University, Center on Globalization, Governance and Competitiveness (Duke CGGC) The Duke University Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness (Duke CGGC) is affiliated with the Social Science Research Institute at Duke University. Duke CGGC is a center of excellence in the United States that uses a global value chains methodology to study the effects of globalization in terms of economic, social, and environmental upgrading, international competitiveness and innovation in the knowledge economy. -

Preliminary Results from Kenya

This article was downloaded by: [the Bodleian Libraries of the University of Oxford] On: 18 May 2012, At: 08:46 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raza20 Exploring agriculture, interaction and trade on the eastern African littoral: preliminary results from Kenya Richard Helm a , Alison Crowther b , Ceri Shipton c , Amini Tengeza d , Dorian Fuller e & Nicole Boivin b a Canterbury Archaeological Trust, 92a Broad Street, Canterbury, CT1 2LU, United Kingdom b Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3QY, United Kingdom c School of Social Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, 4072, Australia d Coastal Forest Conservation Unit, National Museums of Kenya, PO Box 596, Kilifi, Kenya e Institute of Archaeology, University College London, 31–34 Gordon Square, London, WC1H 0PY, United Kingdom Available online: 27 Feb 2012 To cite this article: Richard Helm, Alison Crowther, Ceri Shipton, Amini Tengeza, Dorian Fuller & Nicole Boivin (2012): Exploring agriculture, interaction and trade on the eastern African littoral: preliminary results from Kenya, Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 47:1, 39-63 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2011.647947 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. -

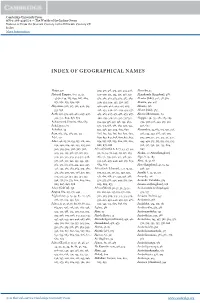

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

Subsistence Mosaics, Forager-Farmer Interactions, and the Transition to Food Production in Eastern Africa

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e20 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Subsistence mosaics, forager-farmer interactions, and the transition to food production in eastern Africa * Alison Crowther a, , Mary E. Prendergast b, Dorian Q. Fuller c, Nicole Boivin d a School of Social Science, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, 4072, Australia b Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 02138, USA c Institute of Archaeology, University College London, London, WC1H 0PY, United Kingdom d Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, 07745, Germany article info abstract Article history: The spread of agriculture across sub-Saharan Africa has long been attributed to the large-scale migration Received 16 March 2016 of Bantu-speaking groups out of their west Central African homeland from about 4000 years ago. These Received in revised form groups are seen as having expanded rapidly across the sub-continent, carrying an ‘Iron Age’ package of 8 December 2016 farming, metal-working, and pottery, and largely replacing pre-existing hunter-gatherers along the way. Accepted 13 January 2017 While elements of the ‘traditional’ Bantu model have been deconstructed in recent years, one of the main Available online xxx constraints on developing a more nuanced understanding of the local processes involved in the spread of farming has been the lack of detailed archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological sequences, particularly Keywords: Bantu expansion from key regions such as eastern Africa. Situated at a crossroads between continental Africa and the Iron age Indian Ocean, eastern Africa was not only a major corridor on one of the proposed Bantu routes to Pastoralism southern Africa, but also the recipient of several migrations of pastoral groups from the north. -

PDF File Generated From

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box