Project Document PAD Revised

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Burundi

Report No: ACS14147 . Public Disclosure Authorized Republic of Burundi Strategies for Urbanization and Public Disclosure Authorized Economic Competitiveness in Burundi . June 19, 2015 . GSURR Public Disclosure Authorized AFRICA . Public Disclosure Authorized Strategies for Urbanization and Economic Competitiveness in Burundi Standard Disclaimer: . This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: . The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

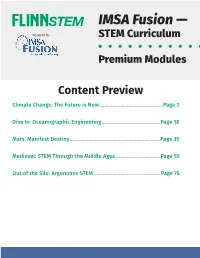

IMSA Fusion — Powered by STEM Curriculum

IMSA Fusion — Powered by STEM Curriculum Premium Modules Content Preview Climate Change: The Future is Now ................................................Page 2 Dive In: Oceanographic Engineering ............................................Page 18 Mars: Manifest Destiny ....................................................................Page 35 Medieval: STEM Through the Middle Ages ..................................Page 59 Out of the Silo: Argonomic STEM ..................................................Page 76 IMSA Fusion — Powered by Climate Change STEM Curriculum Module Table of Contents Unit Objectives, Standards, Overview ................................................................................1 Unit Summaries, Acknowledgments .................................................................................. 9 Materials ..................................................................................................................................15 Unit 1: It’s the L.A.W. ..............................................................................................................17 Unit 2: Where Next? ...............................................................................................................21 Unit 3: The Greenhouse Effect ........................................................................................... 25 Unit 4: Footprints .................................................................................................................. 29 Unit 5: Designer Bags? ..........................................................................................................31 -

FARMERS in the Driver's Seat

FARMERS IN THE FARMERS FARMERS IN THE Properly functioning farmer organizations are essential to enable smallholder agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa to become more productive and profitable. Farmer organizations allow for collective action by smallholders, creating economies of scale, reducing transaction costs and thereby improving access to driver’s seaT markets. In order to sustain income generation through marketing of agricultural products, farmers and their organizations need to maintain their competitiveness and hence reinforce their capacity to innovate. driver’s seaT Innovation in smallholder agriculture in Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya and Rwanda The Association for Strengthening Agricultural Research in Eastern and Central Africa (ASARECA), through its Knowledge Management and Up-Scaling (KMUS) programme, initiated the ‘farmer empowerment for innovation in smallholder agriculture’ (FEISA) project (2010-2013). The project aimed to empower smallholder farmers in Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya and Rwanda to improve their productivity in selected value chains. The project put farmers in the driver’s seat by providing farmer organizations with tools and skills to enhance collaboration with private enterprises, as well as service providers, in multi-stakeholder ‘inno- vation triangles’ within value chains for the benefit of smallholder farmers. Built around case studies from the four countries, this book presents the innova- tion triangle approach, as well as a self-assessment tool for service provision by apex farmer organizations to their members. Both the innovation processes followed, and the results obtained, provide valuable insights on the facilitation of multi-stakeholder platforms for farmer-led innovation in value chains. These insights particularly focus on the role of, and services provided by, apex and grassroots farmer organizations for enhanced market access. -

Lake Tanganyika, Regional Fisheries Programme (TREFIP)

FAO/NORWAY GOVERNMENT GCP/INT/648/NOR COOPERATIVE PROGRAMME Field Report F-14 (En) eries FISHCODE MANAGEMENT LAKE TANGANYIKA REGIONAL FISHERIES PROGRAMME (TREFIP) PREPARED BY THE JOINT AfDB/FAO/FISHCODE MISSION C. MAGNET, J.E. REYNOLDS AND H. BRU FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS ROME, JULY 2000 FAO/Norway Programme of Assistance to Developing Countries for the Implementation of the Code of Conduct for Responsible of the Code Conduct FAO/NorwayFish Programme of Assistance to Developing Countries for the Implementation Fisheries Management for the Provision Advice of Scientific for Improving Countries to Developing Assistance F: Sub-programme LAKE TANGANYIKA REGIONAL FISHERIES PROGRAMME (TREFIP) A proposal for implementation of the Lake Tanganyika Framework Fisheries Management Plan Prepared by: The Joint AfDB/FAO/FISHCODE Lake Tanganyika Mission Christophe Magnet (Team Leader/Economist, AfDB), J.Eric Reynolds (Development Planner/Socio-Economist, FAO), & Hervé Bru (Infrastructure/Marketing Specialist, AfDB) African Development Bank, Food and Agriculture Organization Abidjan of the United Nations, Rome July 2000 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. LAKE TANGANYIKA REGIONAL FISHERIES PROGRAMME (TREFIP) 18.07.00 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document was drafted on behalf of the AfDB and the four Lake Tanganyika littoral States of Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Tanzania, and Zambia. Responsibility for its preparation was assigned to the Fisheries Policy and Planning Service (FIPP) of FAO, with funding provided by the AfDB and the FAO FISHCODE Programme (GCP/INT/648/NOR -- Interregional Programme of Assistance to Developing Countries for the Implementation of the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries). -

Climate Proofing Food Production Investments in Imbo and Moso Basins in the Republic of Burundi

SAP017: Climate proofing food production investments in Imbo and Moso basins in the Republic of Burundi | | Burundi International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) Decision B.27/01 13 November 2020 Climate proofing food production investments in Imbo and Moso Project/Programme title: basins in the Republic of Burundi Country(ies): Burundi National Designated Ministry of Environment, Agriculture, and Breeding Authority(ies): Accredited Entity: International Fund for Agricultural Development Date of first submission: 4/24/2020 V.1 Date of current submission/ 8/11/2020 V.9 version number If available, indicate GCF code: 5d1e03bdab5322bd79f4a27d GREEN CLIMATE FUND SAP FUNDING PROPOSAL |Page 1 of 34 Contents Section A PROJECT / PROGRAMME SUMMARY This section highlights some of the project’s or programme’s information for ease of access and concise explanation of the funding proposal. Section B PROJECT / PROGRAMME DETAILS This section focuses on describing the context of the project/programme, providing details of the project/programme including components, outputs and activities, and implementation arrangements. Section C FINANCING INFORMATION This section explains the financial instrument(s) and amount of funding requested from the GCF as well as co-financing leveraged for the project/programme. It also includes justification for requesting GCF funding and exit strategy. Section D LOGIC FRAMEWORK, AND MONITORING, REPORTING AND EVALUATION This section includes the logic framework for the project/programme in accordance with the GCF Results Management Framework and Performance Measurement Framework, and gives an overview of the monitoring, reporting and evaluation arrangements for the proposed project/programme. Section E EXPECTED PERFORMANCE AGAINST INVESTMENT CRITERIA This section provides an overview of the expected alignment of the projects/programme with the GCF investment criteria: impact potential, paradigm shift, sustainable development, needs of recipients, country ownership, and efficiency and effectiveness. -

Burundi Landscape Analysis

Integrating Gender and Nutrition within Agricultural Extension Services Burundi Landscape Analysis Prepared by Nargiza Ludgate and S. Joyous Tata September 2015 1 © INGENAES This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. Users are free: • To share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work. (without participant contact information) • To remix — to adapt the work. Under the following conditions: • Attribution — users must attribute the work to the authors but not in any way that suggests that the authors endorse the user or the user’s use of the work. Technical editing and production by Nargiza Ludgate, Joyous Tata, and Katy Heinz This report was produced as part of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and US Government Feed the Future project “Integrating Gender and Nutrition within Extension and Advisory Services” (INGENAES). www.ingenaes.illinois.edu Leader with Associates Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-LA-14-00008. The report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through USAID. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. Burundi Landscape Analysis Working document Prepared by Nargiza S. Ludgate, University of Florida Joyous S. Tata, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Cover photo by Doug Satre 2015 Burundi Landscape Study - September 2015 Abbreviations AFR/SD Bureau for Africa/Office of Sustainable Development BFS Bureau for Food Security Burundi -

US Forest Service International Programs, Department of Agriculture

US Forest Service International Programs, Department of Agriculture Republic of Burundi Technical Assistance to the US Government Mission in Burundi on Natural Resource Management and Land Use Policy Mission Dates: September 9 – 22, 2006 Constance Athman Mike Chaveas Hydrologist Africa Program Specialist Mt. Hood National Forest Office of International Programs 16400 Champion Way 1099 14th St NW, Suite 5500W Sandy, OR 97055 Washington, DC 20005 (503) 668-1672 (202) 273-4744 [email protected] [email protected] Jeanne Evenden Director of Lands Intermountain Region 324 25th Street Ogden, UT 84401 (801) 625-5150 [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to extend our gratitude to all those who supported this mission to Burundi. In particular we would like acknowledge Ann Breiter, Deputy Chief of Mission at the US Embassy in Bujumbura for her interest in getting the US Forest Service involved in the natural resource management issues facing Burundi. We would also like to thank US Ambassador Patricia Moller for her strong interest in this work and for the support of all her staff at the US Embassy. Additionally, we are grateful to the USAID staff that provided extensive technical and logistical support prior to our arrival, as well as throughout our time in Burundi. Laura Pavlovic, Alice Nibitanga and Radegonde Bijeje were unrelentingly helpful throughout our visit and fountains of knowledge about the country, the culture, and the history of the region, as well as the various ongoing activities and actors involved in development and natural resource management programs. We would also like to express our gratitude to the Minister of Environment, Odette Kayitesi, for taking the time to meet with our team and for making key members of her staff available to accompany us during our field visits. -

Climate Response of Dahurian Larch in Secrest Arboretum, Wooster, Ohio, USA

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232668913 Climate Response of Dahurian Larch in Secrest Arboretum, Wooster, Ohio, USA Article in Tree-Ring Research · September 2009 DOI: 10.3959/1536-1098-63.2.111 CITATIONS READS 0 88 3 authors, including: Greg Wiles College of Wooster 110 PUBLICATIONS 2,514 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Characterization of glacier-dammed lakes through space and time View project All content following this page was uploaded by Greg Wiles on 13 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. TREE-RING RESEARCH, Vol. 63(2), 2007, pp. 111–115 RESEARCH REPORT CLIMATE RESPONSE OF DAHURIAN LARCH IN SECREST ARBORETUM, WOOSTER, OHIO, USA TYLER MOORE, NATHAN MALCOMB, and GREGORY WILES* Department of Geology The College of Wooster Wooster, OH 44691, USA ABSTRACT Larix gmelinii (Rupr.) Kuzen. (Dahurian larch) is an important arctic tree-line species in the northern boreal forests of Eurasia. The region’s climate is predicted to change dramatically over the next century, yet little is known about how this species will respond to secular changes in temperature and precipitation. To this end, a ring-width chronology from 25 cores from a stand of seven Dahurian larch trees growing in the Secrest Arboretum, northeastern Ohio, was developed to test the climatic sensitivity of the species in a more temperate climate. The chronology extends from 1931 to 2005 and correlation analysis with monthly precipitation and temperature records shows growth was most strongly limited by summer precipitation until recent decades when sensitivity has shifted to late spring precipitation. -

Lake Profile Brief This Is Based on the Results of Multiple Lake Threat Assessment and Its Scenario Analysis

Lake Profile Brief This is based on the results of Multiple Lake Threat Assessment and its Scenario Analysis. Refer to the Technical Report for details. Lake Rweru/Moereo Geographic Information Lake Rweru is located in central Africa, close to the northernmost point of Burundi, with its northern shore forming part of the Burundi‐Rwanda border. The lake is surrounded by marshes and papyrus, and contains floating islands. It is considered by many to be the most distant starting point of the Nile River, in that the Kagera River, which rises at the northern part of the lake, is considered to be the starting point of the Nile. The lake hosts limited fishing activities, and is being increasingly invaded by water hyacinth. Lake Rweru could be a subject for GEF‐catalyzed management interventions, along with Lakes Cohoha and Ihema, with all three lakes located in the same general proximity in the upper catchment wetland region of the riparian countries, and sharing similar economic (fishery management) and environmental (progressing eutrophicatio) challenges. Effectively considering these lakes for such management interventions may require a new strategic approach that considers them as a lake cluster comprising both transboundary and national (non‐transboundary) lake basins. TWAP Regional Eastern & Southern Africa Lake Basin Population (2010) 359,565 Designation Lake Basin Population Density River Basin Nile 284.9 (2010; # km‐2) Average Basin Precipitation Riparian Countries Burundi, Rwanda 938.7 (mm yr‐1) Basin Area (km2) 941.6 Shoreline Length -

Climate Proofing Agricultural Investments Under the National Program for Food Security and Rural Development in Imbo and Moso (PNSADR-IM)

Climate Proofing Agricultural investments under the National Program for Food Security and Rural Development in Imbo and Moso (PNSADR-IM) | Burundi IFAD 20 September 2019 Climate Proofing Agricultural investments under the National Project/Programme title: Program for Food Security and Rural Development in Imbo and Moso (PNSADR-IM) Country(ies): Burundi National Designated Ministry of Environment, Agriculture, and Breeding Authority(ies) (NDA): Africa Sustainability Centre (ASCENT), PNSADR-IM Project Executing Entities: Management Unit (PMU) Accredited Entity(ies) (AE): International Fund for Agricultural Development Date of first submission/ 7/16/2019 V.1 version number: Date of current submission/ 9/20/2019 V.2 version number A. Project / Programme Information (max. 1 page) ☒ Project ☒ Public sector A.2. Public or A.1. Project or programme A.3 RFP Not applicable private sector ☐ Programme ☐ Private sector Mitigation: Reduced emissions from: ☐ Energy access and power generation: 0% ☐ Low emission transport: 0% ☐ Buildings, cities and industries and appliances: 0% A.4. Indicate the result ☐ Forestry and land use: 0% areas for the project/programme Adaptation: Increased resilience of: ☒ Most vulnerable people and communities: 33.333% ☒ Health and well-being, and food and water security: 33.333% ☐ Infrastructure and built environment: 0% ☒ Ecosystem and ecosystem services: 33.333% A.5.1. Estimated mitigation impact (tCO2eq over project lifespan) A.5.2. Estimated adaptation impact 333,450 direct beneficiaries (number of direct beneficiaries) A.5. Impact potential A.5.3. Estimated adaptation impact 2,003,450 indirect beneficiaries (number of indirect beneficiaries) A.5.4. Estimated adaptation impact 20% of the country’s total population (% of total population) A.6. -

WP24 Scoping Paper Burundi

A Scoping Study on Burundi’s Agricultural Production in a Changing Climate and the Supporting Policies Alexis Ndayiragije Desire Mkezabahizi Jean Ndimubandi Francoise Kabogoye Bureau for Agricultural Consultancy Service KIPPRA Working Paper No. 24 2017 A scoping study on Burundi’s agricultural production KIPPRA in Brief The Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA) is an autonomous institute whose primary mission is to conduct public policy research leading to policy advice. KIPPRA’s mission is to produce consistently high-quality analysis of key issues of public policy and to contribute to the achievement of national long-term development objectives by positively infuencing the decision-making process. These goals are met through efective dissemination of recommendations resulting from analysis and by training policy analysts in the public sector. KIPPRA therefore produces a body of well-researched and documented information on public policy, and in the process assists in formulating long-term strategic perspectives. KIPPRA serves as a centralized source from which the Government and the private sector may obtain information and advice on public policy issues. UNECA in Brief Established by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) of the United Nations (UN) in 1958 as one of the UN’s fve regional commissions, ECA’s mandate is to promote the economic and social development of its member States, foster intra-regional integration, and promote international cooperation for Africa’s development. Made up of 54 member States, and playing a dual role as a regional arm of the UN and as a key component of the African institutional landscape, ECA is well positioned to make unique contributions to address the Continent’s development challenges. -

The Water Resources of the Nile Basin

Chapter 2 The Water Resources of the Nile Basin 500 Soroti (1914–2003) 400 300 200 100 Average monthly rainfall 0 JFMAMJ JASOND 25 KEY MESSAGES • The Nile Basin is characterized by high climatic • The headwater regions of the Nile are subject diversity and variability, a low percentage of rainfall to widespread soil erosion. Sediment yields are reaching the main river, and an uneven distribution particularly high in the Eastern Nile sub-basin, of its water resources. Potential evaporation rates which contributes 97 per cent of the total sediment in the Nile region are high, making the basin load. Most sediment is captured in reservoirs in The particularly vulnerable to drought. Sudan and Egypt, which leads to a rapid loss of • White Nile flows only contribute up to 15 per cent reservoir storage capacity. of the annual Nile discharge, but are fairly stable • The finite Nile flows are now fully utilized for throughout the year. The Eastern Nile region agricultural, domestic, industrial, and environmental supplies up to 90 per cent of annual Nile flows, but purposes, while water demand continues to rise its contribution is highly seasonal. steadily due to population growth and economic • Extensive regional aquifer systems holding development. substantial quantities of groundwater underlie the • Irrigated agriculture in Egypt and The Sudan Nile region. Some of the aquifers hold fossil water, represents the single most important consumer but others are recharged from precipitation over of the waters of the Nile, but the upper riparians the basin, or from irrigation areas and the baseflow are planning investments that will use the river’s of the Nile.