Learning About Life Culture in Home Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Acculturation Process for Kaigaishijo: a Qualitative Study of Four Japanese Students in an American School

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 The acculturation process for kaigaishijo: A qualitative study of four Japanese students in an American school Linda F. Harkins College of William & Mary - School of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Personality and Social Contexts Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Harkins, Linda F., "The acculturation process for kaigaishijo: A qualitative study of four Japanese students in an American school" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539618735. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25774/w4-6dp2-fn37 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORM ATION TO U SE R S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

1423778527171.Pdf

Bahamut - [email protected] Based on the “Touhou Project” series of games by Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN. http://www16.big.or.jp/~zun/ The Touhou Project and its related properties are ©Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN. The Team Shanghai Alice logo is ©Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN. Illustrations © their respective owners. Used without permission. Tale of Phantasmal Land text & gameplay ©2011 Bahamut. This document is provided “as is”. Your possession of this document, either in an altered or unaltered state signifies that you agree to absolve, excuse, or otherwise not hold responsible Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN and/or Bahamut, and/or any other individuals or entities whose works appear herein for any and/or all liabilities, damages, etc. associated with the possession of this document. This document is not associated with, or endorsed by Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN. This is a not-for-profit personal interest work, and is not intended, nor should it be construed, as a challenge to Team Shanghai Alice / ZUN’s ownership of its Touhou Project copyrights and other related properties. License to distribute this work is freely given provided that it remains in an unaltered state and is not used for any commercial purposes whatsoever. All Rights Reserved. Introduction Choosing a Race (Cont.’d) What Is This Game All About? . 1 Magician . .20 Too Long; Didn’t Read Version . 1 Moon Rabbit . .20 Here’s the Situation . 1 Oni . .21 But Wait! There’s More! . 1 Tengu . .21 Crow Tengu . .22 About This Game . 2 White Wolf Tengu . .22 About the Touhou Project . 2 Vampire . .23 About Role-Playing Games . -

A Set of Japanese Word Cohorts Rated for Relative Familiarity

A SET OF JAPANESE WORD COHORTS RATED FOR RELATIVE FAMILIARITY Takashi Otake and Anne Cutler Dokkyo University and Max-Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT are asked to guess about the identity of a speech signal which is in some way difficult to perceive; in gating the input is fragmentary, A database is presented of relative familiarity ratings for 24 sets of but other methods involve presentation of filtered or noise-masked Japanese words, each set comprising words overlapping in the or faint signals. In most such studies there is a strong familiarity initial portions. These ratings are useful for the generation of effect: listeners guess words which are familiar to them rather than material sets for research in the recognition of spoken words. words which are unfamiliar. The above list suggests that the same was true in this study. However, in order to establish that this was 1. INTRODUCTION so, it was necessary to compare the relative familiarity of the guessed words and the actually presented words. Unfortunately Spoken-language recognition proceeds in time - the beginnings of we found no existing database available for such a comparison. words arrive before the ends. Research on spoken-language recognition thus often makes use of words which begin similarly It was therefore necessary to collect familiarity ratings for the and diverge at a later point. For instance, Marslen-Wilson and words in question. Studies of subjective familiarity rating 1) 2) Zwitserlood and Zwitserlood examined the associates activated (Gernsbacher8), Kreuz9)) have shown very high inter-rater by the presentation of fragments which could be the beginning of reliability and a better correlation with experimental results in more than one word - in Zwitserlood's experiment, for example, language processing than is found for frequency counts based on the fragment kapit- which could begin the Dutch words kapitein written text. -

Identification of Asian Garments in Small Museums

AN ABSTRACTOF THE THESIS OF Alison E. Kondo for the degree ofMaster ofScience in Apparel Interiors, Housing and Merchandising presented on June 7, 2000. Title: Identification ofAsian Garments in Small Museums. Redacted for privacy Abstract approved: Elaine Pedersen The frequent misidentification ofAsian garments in small museum collections indicated the need for a garment identification system specifically for use in differentiating the various forms ofAsian clothing. The decision tree system proposed in this thesis is intended to provide an instrument to distinguish the clothing styles ofJapan, China, Korea, Tibet, and northern Nepal which are found most frequently in museum clothing collections. The first step ofthe decision tree uses the shape ofthe neckline to distinguish the garment's country oforigin. The second step ofthe decision tree uses the sleeve shape to determine factors such as the gender and marital status ofthe wearer, and the formality level ofthe garment. The decision tree instrument was tested with a sample population of 10 undergraduates representing volunteer docents and 4 graduate students representing curators ofa small museum. The subjects were asked to determine the country oforigin, the original wearer's gender and marital status, and the garment's formality and function, as appropriate. The test was successful in identifying the country oforigin ofall 12 Asian garments and had less successful results for the remaining variables. Copyright by Alison E. Kondo June 7, 2000 All rights Reserved Identification ofAsian Garments in Small Museums by Alison E. Kondo A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master ofScience Presented June 7, 2000 Commencement June 2001 Master of Science thesis ofAlison E. -

The Sexual Life of Japan : Being an Exhaustive Study of the Nightless City Or the "History of the Yoshiwara Yūkwaku"

Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924012541797 Cornell University Library HQ 247.T6D27 1905 *erng an exhau The sexual life of Japan 3 1924 012 541 797 THE SEXUAL LIFE OF JAPAN THE SEXUAL LIFE OF JAPAN BEING AN EXHAUSTIVE STUDY OF THE NIGHTLESS CITY 1^ ^ m Or the "HISTORY of THE YOSHIWARA YUKWAKU " By J, E. DE BECKER "virtuous men hiive siitd, both in poetry and ulasslo works, that houses of debauch, for women of pleasure and for atreet- walkers, are the worm- eaten spots of cities and towns. But these are necessary evils, and If they be forcibly abolished, men of un- righteous principles will become like ravelled thread." 73rd section of the " Legacy of Ityasu," (the first 'I'okugawa ShOgun) DSitl) Niimrraiia SUuatratiuna Privately Printed . Contents PAGE History of the Yosliiwara Yukwaku 1 Nilion-dzutsumi ( 7%e Dyke of Japan) 15 Mi-kaeri Yanagi [Oazing back WUlow-tree) 16 Yosliiwara Jiuja ( Yoahiwara Shrine) 17 The "Aisome-zakura " {Chen-y-tree of First Meeting) 18 The " Koma-tsunagi-matsu " {Colt tethering Pine-tree) 18 The " Ryojin no Ido " {Traveller's Well) 18 Governmeut Edict-board and Regulations at the Omen (Great Gate) . 18 The Present Omon 19 »Of the Reasons why going to the Yosliiwara was called " Oho ve Yukn " ". 21 Classes of Brothels 21 Hikite-jaya (" Introducing Tea-houses"') 28 The Ju-hachi-ken-jaya (^Eighteen Tea-houses) 41 The " Amigasa-jaya -

Memoirs of a Geisha Arthur Golden Chapter One Suppose That You and I Were Sitting in a Quiet Room Overlooking a Gar-1 Den, Chatt

Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html Memoirs Of A Geisha Arthur Golden Chapter one Suppose that you and I were sitting in a quiet room overlooking a gar-1 den, chatting and sipping at our cups of green tea while we talked J about something that had happened a long while ago, and I said to you, "That afternoon when I met so-and-so . was the very best afternoon of my life, and also the very worst afternoon." I expect you might put down your teacup and say, "Well, now, which was it? Was it the best or the worst? Because it can't possibly have been both!" Ordinarily I'd have to laugh at myself and agree with you. But the truth is that the afternoon when I met Mr. Tanaka Ichiro really was the best and the worst of my life. He seemed so fascinating to me, even the fish smell on his hands was a kind of perfume. If I had never known him, I'm sure I would not have become a geisha. I wasn't born and raised to be a Kyoto geisha. I wasn't even born in Kyoto. I'm a fisherman's daughter from a little town called Yoroido on the Sea of Japan. In all my life I've never told more than a handful of people anything at all about Yoroido, or about the house in which I grew up, or about my mother and father, or my older sister-and certainly not about how I became a geisha, or what it was like to be one. -

Noh Theater and Religion in Medieval Japan

Copyright 2016 Dunja Jelesijevic RITUALS OF THE ENCHANTED WORLD: NOH THEATER AND RELIGION IN MEDIEVAL JAPAN BY DUNJA JELESIJEVIC DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in East Asian Languages and Cultures in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Elizabeth Oyler, Chair Associate Professor Brian Ruppert, Director of Research Associate Professor Alexander Mayer Professor Emeritus Ronald Toby Abstract This study explores of the religious underpinnings of medieval Noh theater and its operating as a form of ritual. As a multifaceted performance art and genre of literature, Noh is understood as having rich and diverse religious influences, but is often studied as a predominantly artistic and literary form that moved away from its religious/ritual origin. This study aims to recapture some of the Noh’s religious aura and reclaim its religious efficacy, by exploring the ways in which the art and performance of Noh contributed to broader religious contexts of medieval Japan. Chapter One, the Introduction, provides the background necessary to establish the context for analyzing a selection of Noh plays which serve as case studies of Noh’s religious and ritual functioning. Historical and cultural context of Noh for this study is set up as a medieval Japanese world view, which is an enchanted world with blurred boundaries between the visible and invisible world, human and non-human, sentient and non-sentient, enlightened and conditioned. The introduction traces the religious and ritual origins of Noh theater, and establishes the characteristics of the genre that make it possible for Noh to be offered up as an alternative to the mainstream ritual, and proposes an analysis of this ritual through dynamic and evolving schemes of ritualization and mythmaking, rather than ritual as a superimposed structure. -

Young Audiences of Massachusetts Educational Materials

Young Audiences of Massachusetts Educational Materials Please forward to teachers 4/14/10 ABOUT THE PERFORMANCE Odaiko New England Grade levels: K-5 Odiako New England demonstrates the ancient art form of taiko (Japanese drumming) and its importance in Japanese culture. This energetic and engaging program highlights kumidaiko (ensemble drumming) and combines traditional taiko rhythms with dynamic movement and rhythms from other musical traditions. Students explore kata (a drumming technique) and the concept of kiai (vocalizing energy) and join the performers on stage to play the taiko drums. LEARNING GOALS: 1. To experience and learn techniques of Japanese taiko drumming. 2. To explore the history of Japanese taiko drumming and its historical and contemporary role in Japanese culture and traditions. PRE-ACTIVITY SUMMARY: Understanding Musical Rhythms Discuss the concept of rhythm. Ask students to identify everyday rhythms they can see, hear, and replicate through movement. Have students create different percussive sounds with their bodies (snapping fingers, clapping hands, stomping feet, etc.). Create a rhythm for the rest of the class to echo. Repeat the pattern until everyone can do it. Encourage each student to demonstrate his/her own rhythm for the rest of the class. © San Jose Taiko POST-ACTIVITY SUMMARY: Family Symbols Discuss the origin of the Japanese family crest (information enclosed). Discuss how symbols represent ideas and stories. Discuss students’ surnames and the possible origins of the names. Have students select a symbol to represent their family name. Ask students to cre- ate Japanese family crests. Have them present their family crest to the class and discuss their specific design choice. -

Move Then Skin Deep

More than Skin Deep: Masochism in Japanese Women’s Writing 1960-2005 by Emerald Louise King School of Asian Languages and Studies Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Arts) University of Tasmania, November 2012 Declaration of Originality “This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and dully acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgment is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright.” Sections of this thesis have been presented at the 2008 Australian National University Asia Pacific Week in Canberra, the 2008 University of Queensland Rhizomes Conference in Queensland, the 2008 Asian Studies Association of Australia Conference in Melbourne, the 2008 Women in Asia Conference in Queensland, the 2010 East Asian Studies Graduate Student Conference in Toronto, the 2010 Women in Asia Conference in Canberra, and the 2011 Japanese Studies Association of Australia Conference in Melbourne. Date: ___________________. Signed: __________________. Emerald L King ii Authority of Access This thesis is not to made available for loan or copying for two years following the date this statement was signed. Following that time the thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Date: ___________________. Signed: __________________. Emerald L King iii Statement of Ethical Conduct “The research associated with this thesis abides by the international and Australian codes on human and animal experimentation, the guidelines by the Australian Government's Office of the Gene Technology Regulator and the rulings of the Safety, Ethics and Institutional Biosafety Committees of the University.” Date: ___________________. -

LANDMARK English Communication I「発問シナリオ」(授業展開)サンプル

LANDMARK English Communication I「発問シナリオ」(授業展開)サンプル 本文理解の深さを問う発問活動(各パート Q&A 活動)Can-Do 尺度例 「教科書本文を読んで、本文の流れを踏まえて重要な内容を理解することができる」 ① 前提となる背景的事実や出来事について答えることが難しい。 ② 前提となる背景的事実や出来事について答えることができる。 …… ②「前提」発問 ③ 中心の命題(イイタイコト)について答えることができる。 …… ③「命題」発問 ④ 背後の理由や詳細情報などの展開について答えることができる。 …… ④「展開」発問 ※ Teacher’s Manual ⑦「Can-Do リスト解説書」(pp.6-8)参照 Lesson 3 “School Uniforms” 発問シナリオ概要 発問を通して本文の理解確認を行い、授業への深い理解を促すことを目的としている。教科書の 脚注質問を、中心の命題(イイタイコト)発問と位置づけ、その前提となる背景的事実や出来事を 引き出す発問と予想される生徒の回答をシナリオ化している。パートごとに、発話内容ごとにラベ リングをしているので、発話の流れと内容を確認できるようになっている。字義的な理解にとどま らず、深い内容理解のための推測発問例を示している。パート2・3に関しては、教師が補足的情 報を提示しながら、より深い理解を促す発問例になっている。特に【Advanced】のパートについて は、生徒の理解に応じて利用してほしい。パート4においては、制服着用の是非について賛否両論 の意見を理解しながら、生徒がさらに発展的にディスカッションを行う発問例を提示している。 Lesson 3 “School Uniforms” 【Part 1】 【イントロダクション】 T: What do you wear when you go to school every day? S: I wear my school uniform, of course. T: Yes, of course you do. Look at the pie chart on page 36. As you know, most Japanese high schools have school uniforms. ②How many senior high schools have a school uniform? S: 81% have school uniforms. T: Correct. Actually, most Japanese high schools and junior high schools have school uniforms. ②What percent of Japanese people wore school uniforms during their school days? S: More than 95% of them did. T: That’s right. In Japan, most Japanese people wore school uniforms when they were students. T:【Advanced】Look at these two numbers. Why are these two numbers different? Why do you think the second one is higher than the first one? S: Because the first one is about high schools, but the second one shows junior and high schools. I think wearing a school uniform is more popular in junior high schools. T: Good notice! Sometimes you have a choice to wear private clothes even when your school has a school uniform. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

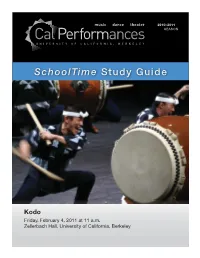

Kodo Study Guide 1011.Indd

2010–2011 SEASON SchoolTime Study Guide Kodo Friday, February 4, 2011 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime On Friday, February 4 at 11am, your class will att end a SchoolTime performance of Kodo (Taiko drumming) at Cal Performances’ Zellerbach Hall. In Japan, “Kodo” meana either “hearbeat” or “children of the drum.” These versati le performers play a variety of instruments – some massive in size, some extraordinarily delicate that mesmerize audiences. Performing in unison, they wield their sti cks like expert swordsmen, evoking thrilling images of ancient and modern Japan. Witnessing a performance by Kodo inspires primal feelings, like plugging into the pulse of the universe itself. Using This Study Guide You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Cal Performances fi eld trip. Before att ending the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the Student Resource Sheet on pages 2 & 3 for your students to use before the show. • Discuss the informati on on pages 4-5 About the Performance & Arti sts. • Read About the Art Form on page 6, and About Japan on page 11 with your students. • Engage your class in two or more acti viti es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect by asking students the guiding questi ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 11. • Immerse students further into the subject matt er and art form by using the Resource and Glossary secti ons on pages 15 & 16. At the performance: Your class can acti vely parti cipate during the performance by: • Listening to Kodo’s powerful drum rhythms and expressive music • Observing how the performers’ movements and gestures enhance the performance • Thinking about how you are experiencing a bit of Japanese culture and history by att ending a live performance of taiko drumming • Marveling at the skill of the performers • Refl ecti ng on the sounds, sights, and performance skills you experience at the theater.