Basic Problems in Playing the Cornet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-Brass-Audition-Packet.Pdf

Dear Brass Line Candidate, Thank you for your interest in the 7th Regiment Drum and Bugle Corps! This packet will serve as your primary resource for video auditions. Read everything in this booklet carefully and prepare all of the required materials to the best of your ability. VISUAL AUDITION MATERIALS Basics of Marching Technique: Our technique program is “straight leg” marching; that is, we strive for the longest line between our hip and ankle bone at all times. Allowing the leg to bend at the knee shortens that line. The following are basic definitions for those who are unfamiliar with our technique. ● We stand in first position. With your heels together you will turn your feet outward 45 degrees. This turnout will come from the hips. Make sure your knees are in line with your middle toe. ● Horn Carriage: When at playing position (or carry) create a wide triangle with your forearms and horn. ● Forward March: articulate each beat with the back of your heel as you move forward and generate the longest possible leg line on the crossing counts. ● Backwards March: articulate each beat with the platform of your foot keeping your heel low to the ground as you move backward and generate the longest possible leg line on the crossing counts. ● Crossing Counts: The point at which your ankle bones are right next to each other while marching. This should happen on the ‘& count’ when marching in a duple (4/4) meter. ● 5 Points of Alignment: generate uniform posture by keeping your ears (1), shoulders (2), hips (3), and knees (4) stacked vertically from your ankle bones (5). -

Brass Teacherõs Guide

Teacher’s Guide Brass ® by Robert W.Getchell, Ph. D. Foreword This manual includes only the information most pertinent to the techniques of teaching and playing the instruments of the brass family. Its principal objective is to be of practical help to the instrumental teacher whose major instrument is not brass. In addition, the contents have purposely been arranged to make the manual serve as a basic text for brass technique courses at the college level. The manual should also help the brass player to understand the technical possibilities and limitations of his instrument. But since it does not pretend to be an exhaustive study, it should be supplemented in this last purpose by additional explanation from the instructor or additional reading by the student. General Characteristics of all Brass Instruments Of the many wind instruments, those comprising the brass family are perhaps the most closely interrelated as regards principles of tone production, embouchure, and acoustical characteristics. A discussion of the characteristics common to all brass instruments should be helpful in clarifying certain points concerning the individual instruments of the brass family to be discussed later. TONE PRODUCTION. The principle of tone production in brass instruments is the lip-reed principle, peculiar to instruments of the brass family, and characterized by the vibration of the lip or lips which sets the sound waves in motion. One might describe the lip or lips as the generator, the tubing of the instrument as the resonator, and the bell of the instrument as the amplifier. EMBOUCHURE. It is imperative that prospective brass players be carefully selected, as perhaps the most important measure of success or failure in a brass player, musicianship notwithstanding, is the degree of flexibility and muscular texture in his lips. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Smith, David and Blundel, Richard (2016). Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75. In: Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG) Joint Conference, 27-29 May 2016, Humbolt University, Berlin. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Authors https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ebha.org/public/C6:pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano by Maria Payan, M.M., B.M. A Thesis In Music Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved Dr. Lisa Garner Santa Chair of Committee Dr. Keith Dye Dr. David Shea Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School May 2013 Copyright 2013, Maria Payan Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have started without the extraordinary help and encouragement of Dr. Lisa Garner Santa. The education, time, and support she gave me during my studies at Texas Tech University convey her devotion to her job. I have no words to express my gratitude towards her. In addition, this project could not have been finished without the immense help and patience of Dr. Keith Dye. For his generosity in helping me organize and edit this project, I thank him greatly. Finally, I would like to give my dearest gratitude to Donna Hogan. Without her endless advice and editing, this project would not have been at the level it is today. ii Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

Unit 10.2 the Physics of Music Objectives Notes on a Piano

Unit 10.2 The Physics of Music Teacher: Dr. Van Der Sluys Objectives • The Physics of Music – Strings – Brass and Woodwinds • Tuning - Beats Notes on a Piano Key Note Frquency (Hz) Wavelength (m) 52 C 524 0.637 51 B 494 0.676 50 A# or Bb 466 0.717 49 A 440 0.759 48 G# or Ab 415 0.805 47 G 392 0.852 46 F# or Gb 370 0.903 45 F 349 0.957 44 E 330 1.01 43 D# or Eb 311 1.07 42 D 294 1.14 41 C# or Db 277 1.21 40 C (middle) 262 1.27 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_key_frequencies 1 Vibrating Strings - Fundamental and Overtones A vibration in a string can L = 1/2 λ1 produce a standing wave. L = λ Usually a vibrating string 2 produces a sound whose L = 3/2 λ3 frequency in most cases is constant. Therefore, since L = 2 λ4 frequency characterizes the pitch, the sound produced L = 5/2 λ5 is a constant note. Vibrating L = 3 λ strings are the basis of any 6 string instrument like guitar, L = 7/2 λ7 cello, or piano. For the fundamental, λ = 2 L where Vibration, standing waves in a string, L is the length of the string. The fundamental and the first 6 overtones which form a harmonic series http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vibrating_string Length of Piano Strings The highest key on a piano corresponds to a frequency about 150 times that of the lowest key. If the string for the highest note is 5.0 cm long, how long would the string for the lowest note have to be if it had the same mass per unit length and the same tension? If v = fλ, how are the frequencies and length of strings related? Other String Instruments • All string instruments produce sound from one or more vibrating strings, transferred to the air by the body of the instrument (or by a pickup in the case of electronically- amplified instruments). -

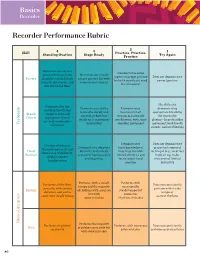

Recorder Performance Rubric

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

Funderburk, Jeff, "The Man and His Horn", T.U.B.A. JOURNAL May, 1988 P 43

Funderburk, Jeff, "The Man and his Horn", T.U.B.A. JOURNAL May, 1988 p 43 This fabulous tuba was reportedly designed by Bill Johnson, design engineer for the J.W. York Band Instrument Company of Grand Rapids, Michigan. According to the story, Leopold Stokowski, conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra in the 1930s, approached the orchestra's tubist, Phillip Donatelli, and requested that he obtain a tuba that would provide a true organ like quality to the bass register of the orchestra. Mr. Donatelli consulted with the York Instrument Company, a firm noted for excellent tubas. Two instruments pitched in CC were built to order. These incorporated a medium-large piston valve section (larger than any built today!) and a large bore rotary fifth valve into the body of a Kaiser tuba with a 20-inch bell diameter. As fate would have it, Mr. Donatelli did not feel comfortable with these instruments. One reason for this was the very short leadpipe used on the instruments. Mr. Donatelli was overweight to the point that when he breathed, the instrument was forced away from him. There was no room on the chair for the two of them! Consequently, the instruments were sold. One instrument was sold to Arnold Jacobs, a student at Curtis Institute, for the price of $175, to be paid off at a rate of $5 per week. Mr. Jacobs and his tuba were so well liked by the orchestra director at the Curtis Institute - Fritz Reiner - that a limousine was sent on rehearsal days to collect the two of them from home. -

Band Director's Catalog

BAND DIRECTor’s CATALOG We make legends. A division of Steinway Musical Instruments, Inc. P.O. Box 310, Elkhart, IN 46515 www.conn-selmer.com AV4230 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Eb Soprano, Harmony & Eb Alto Clarinets ....... 10 Bb Bass, EEb Bass & BBb Bass Clarinets ........... 11 308 Student Instruments Step-Up & Pro Saxophones .............................. 12-13 Step-Up & Pro Bb Trumpets .............................. 14 Piccolos & Flutes ...................................................... 1 Step-Up & Pro Cornets ..................................... 14 Oboes & Clarinets .................................................... 2 C Trumpets, Harmony Trumpets, Flugelhorns .... 15 Saxophones .............................................................. 3 Step-Up & Pro Trombones ................................ 16-17 204 Trumpets & Cornets .................................................. 4 Alto, Valve & Bass Trombones .......................... 18 Trombones ............................................................... 5 Double Horns .................................................. 19 PICCOLOS Single Horns ............................................................ 5 Baritones & Euphoniums .................................. 20 Educational Drum, Bell and Combo Kits .................. 6 BBb Tubas - Three Valve .................................... 21 ARMSTRONG Mallet Instruments .................................................... 6 BBb & CC Tubas - Four Valve ............................ 21 204 “USA” – Silver-plated headjoint and body, silver-plated -

Tutti Brassi

Tutti Brassi A brief description of different ways of sounding brass instruments Jeremy Montagu © Jeremy Montagu 2018 The author’s moral rights have been asserted Hataf Segol Publications 2018 Typeset in XƎLATEX by Simon Montagu Why Mouthpieces 1 Cornets and Bugles 16 Long Trumpets 19 Playing the Handhorn in the French Tradition 26 The Mysteries of Fingerhole Horns 29 Horn Chords and Other Tricks 34 Throat or Overtone Singing 38 iii This began as a dinner conversation with Mark Smith of the Ori- ental Institute here, in connexion with the Tutankhamun trum- pets, and progressed from why these did not have mouthpieces to ‘When were mouthpieces introduced?’, to which, on reflection, the only answer seemed to be ‘Often’, for from the Danish lurs onwards, some trumpets or horns had them and some did not, in so many cultures. But indeed, ‘Why mouthpieces?’ There seem to be two main answers: one to enable the lips to access a tube too narrow for the lips to access unaided, and the other depends on what the trumpeter’s expectations are for the instrument to achieve. In our own culture, from the late Renaissance and Early Baroque onwards, trumpeters expected a great deal, as we can see in Bendinelli’s and Fantini’s tutors, both of which are avail- able in facsimile, and in the concert repertoire from Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo onwards. As a result, mouthpieces were already large, both wide enough and deep enough to allow the player to bend the 11th and 13th partials and other notes easily. The transition from the base of the cup into the backbore was a sharp edge. -

For Release at NAMM 2014 December 3, 2013 Conn-Selmer Is Proud to Announce Its 2014 Launch Line-Up Flutes Saxophones

For Release At NAMM 2014 December 3, 2013 Conn-Selmer is Proud to Announce Its 2014 Launch Line-Up 2014 is going to be a big Music industry year and Conn-Selmer is excited to share these newly, innovated instruments that will invigorate its core categories. Flutes Announcing the new PCR Headjoint. All flute models in the Armstrong line will have the new headjoint. PCR represents increased: Projection Clarity and Response. This new headjoint has the familiar Armstrong durability that everyone loves, with improved sound and playability. Armstrong is Made in the USA and the new headjoints on all models street price ranges from $994 - $1,449. Models are: 102, 102E, 103, 103OS, 104, 303B, 303BOS, 303BEOS, 800B, 800BOF, 800BEF, 800BOFPICC, FLSOL301 and FLSOL201G. Saxophones Revealing the new Selmer Tenor Saxophone, model TS44. This custom designed Henri Selmer Paris neck and mouthpiece comes with a BAM case. With this natural addition, it expands the highly successful 40 Series. MAP is $2,899 and also comes in black nickel (pictured) and silver plate. Both the TS44B and TS44S MAP for $3,265. Trombones Bach Artisan has extended its line of professional trombones. The Artisan Collection is customizable with fully interchangeable components and can become 81 different horns! This horn is adaptable to a variety of trombone artists. You can choose from three (3) bell material options, three (3) valve options, three (3) hand slide options and three (3) tuning slide options, to make it your own sound. It comes in standard models A47 (MAP is $2,758), A47I and A47MLR (MAP is $4,487). -

Instrument Descriptions

RENAISSANCE INSTRUMENTS Shawm and Bagpipes The shawm is a member of a double reed tradition traceable back to ancient Egypt and prominent in many cultures (the Turkish zurna, Chinese so- na, Javanese sruni, Hindu shehnai). In Europe it was combined with brass instruments to form the principal ensemble of the wind band in the 15th and 16th centuries and gave rise in the 1660’s to the Baroque oboe. The reed of the shawm is manipulated directly by the player’s lips, allowing an extended range. The concept of inserting a reed into an airtight bag above a simple pipe is an old one, used in ancient Sumeria and Greece, and found in almost every culture. The bag acts as a reservoir for air, allowing for continuous sound. Many civic and court wind bands of the 15th and early 16th centuries include listings for bagpipes, but later they became the provenance of peasants, used for dances and festivities. Dulcian The dulcian, or bajón, as it was known in Spain, was developed somewhere in the second quarter of the 16th century, an attempt to create a bass reed instrument with a wide range but without the length of a bass shawm. This was accomplished by drilling a bore that doubled back on itself in the same piece of wood, producing an instrument effectively twice as long as the piece of wood that housed it and resulting in a sweeter and softer sound with greater dynamic flexibility. The dulcian provided the bass for brass and reed ensembles throughout its existence. During the 17th century, it became an important solo and continuo instrument and was played into the early 18th century, alongside the jointed bassoon which eventually displaced it. -

Trumpet, Cornet, Flugelhorn GRADE 6 from 2017

Trumpet, Cornet, Flugelhorn GRADE 6 from 2017 PREREQUISITE FOR ENTRY: ABRSM Grade 5 (or above) in Music Theory, Practical Musicianship or any solo Jazz subject. For alternatives, see www.abrsm.org/prerequisite. THREE PIECES: one chosen by the candidate from each of the three Lists, A, B and C: LIST A 1 Albrechtsberger Larghetto: 3rd movt from Concertino (Brass Wind) 2 J. S. Bach Esurientes implevit bonis (from Magnificat). Baroque Around the Clock for Trumpet, arr. Blackadder and Gout (Brass Wind) 3 Fiala Largo (observing cadenza): 1st movt from Divertimento in D (Faber) 4 Gibbons The King’s Juell. No. 4 from Gibbons Keyboard Suite for Trumpet, arr. Cruft (Stainer & Bell 2588: B b/C edition) 5 Handel Allegro: 2nd movt from Sonata (in A b), Op. 1 No. 11. No. 2 from Handel Two Sonatas, trans. Varasdy and Orbán (Editio Musica Budapest Z.13933) 6 Haydn Andante: 2nd movt from Trumpet Concerto in E b, Hob. VIIe/1 (Henle HN 456 or Universal HM 223: B b/E b edition) 7 Mendelssohn Allegretto grazioso only. Mendelssohn Songs without Words Nos 9 and 30, arr. Round (Wright & Round ) 8 Mozart Alleluia (from Exultate Jubilate). Trumpet in Church, arr. Denwood (Emerson E283) 9 Stanley Trumpet Voluntary, Op. 6 No. 5. No. 11 from Old English Trumpet Tunes, Book 1, arr. Lawton (OUP ) LIST B 1 Leroy Anderson A Trumpeter’s Lullaby (Alfred 41061) 2 Gershwin Theme (from Rhapsody in Blue). Concert Repertoire for Trumpet, arr. Calland (Faber) 3 Hubeau Sarabande: 1st movt from Sonata for Trumpet (Durand: B b/C edition) 4 Bryan Kelly Colonel Glib (Retired) or The Chase: No.