HIST 091 Thesis Fall 2019 Una Iglesia Desaparecida: the End of an Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIDOC Guide V1.Pdf

CIDOC Collection The History of Religiosity in Latin America ca. 1830-1970 on microfiches Advisor: Valentina Borremans, El Colegio de Mexico, with the assistance of Ivan Illich / — ^ This is an example of a microfiche. The heading of each fiche indicates clearly (without magnification) the title, volume number(s), and the page numbers on that fiche. Each fiche comes in a protective envelope. Cover illustration: Mano Poderosa, Norberto Cedeno (1966). Collection: I. Curbelo Photo ; I. Curbelo ( JAN 10 1997 ) N^S^OGICAl 'REF BR 600 .G5 1966 v.l CIDOG COLLECTION: History of religiosity in Latin Am. Inter Documentation Company AG Poststrasse 14 6300 Zug Switzerland Telephone 42-214974 Cable address INDOCO, Zug, Switzerland Telex 868819 ZUGAL Bankers Credit Suisse, 6301 Zug, Switzerland, postal checking account of the bank 80-5522; IDC’s account no. 209.646-11 IDC’s processing plant Hogewoerd 151-153, 2311 HK Leiden, The Netherlands CIDOC collection, ca. 1830-1970 Until now it has been impossible for the sociolo gist, the anthropologist, the historian of atti tudes, or the social psychologist to develop the study of religion in modern Latin America into a field of teaching and research. The documents relevant to the colonial period are, of course, preserved and often well edited. But the imprints of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that reflect local devotions and syncretist rituals,' religious iconography and poetry, and .the pastoral campaigns of the various churches and sects, went uncollected and unnoticed until the early 1960s, when Ivan Illich began to search for them and to collect them in the CIDOC Library of Cuernavaca. -

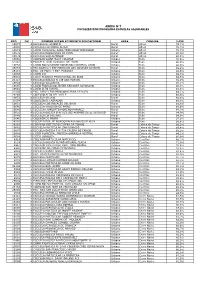

Rbd Dv Nombre Establecimiento

ANEXO N°7 FOCALIZACIÓN PROGRAMA ESCUELAS SALUDABLES RBD DV NOMBRE ESTABLECIMIENTO EDUCACIONAL AREA COMUNA %IVE 10877 4 ESCUELA EL ASIENTO Rural Alhué 74,7% 10880 4 ESCUELA HACIENDA ALHUE Rural Alhué 78,3% 10873 1 LICEO MUNICIPAL SARA TRONCOSO TRONCOSO Urbano Alhué 78,7% 10878 2 ESCUELA BARRANCAS DE PICHI Rural Alhué 80,0% 10879 0 ESCUELA SAN ALFONSO Rural Alhué 90,3% 10662 3 COLEGIO SAINT MARY COLLEGE Urbano Buin 76,5% 31081 6 ESCUELA SAN IGNACIO DE BUIN Urbano Buin 86,0% 10658 5 LICEO POLIVALENTE MODERNO CARDENAL CARO Urbano Buin 86,0% 26015 0 ESC.BASICA Y ESP.MARIA DE LOS ANGELES DE BUIN Rural Buin 88,2% 26111 4 ESC. DE PARV. Y ESP. PUKARAY Urbano Buin 88,6% 10638 0 LICEO 131 Urbano Buin 89,3% 25591 2 LICEO TECNICO PROFESIONAL DE BUIN Urbano Buin 89,5% 26117 3 ESCUELA BÁSICA N 149 SAN MARCEL Urbano Buin 89,9% 10643 7 ESCUELA VILLASECA Urbano Buin 90,1% 10645 3 LICEO FRANCISCO JAVIER KRUGGER ALVARADO Urbano Buin 90,8% 10641 0 LICEO ALTO JAHUEL Urbano Buin 91,8% 31036 0 ESC. PARV.Y ESP MUNDOPALABRA DE BUIN Urbano Buin 92,1% 26269 2 COLEGIO ALTO DEL VALLE Urbano Buin 92,5% 10652 6 ESCUELA VILUCO Rural Buin 92,6% 31054 9 COLEGIO EL LABRADOR Urbano Buin 93,6% 10651 8 ESCUELA LOS ROSALES DEL BAJO Rural Buin 93,8% 10646 1 ESCUELA VALDIVIA DE PAINE Urbano Buin 93,9% 10649 6 ESCUELA HUMBERTO MORENO RAMIREZ Rural Buin 94,3% 10656 9 ESCUELA BASICA G-N°813 LOS AROMOS DE EL RECURSO Rural Buin 94,9% 10648 8 ESCUELA LO SALINAS Rural Buin 94,9% 10640 2 COLEGIO DE MAIPO Urbano Buin 97,9% 26202 1 ESCUELA ESP. -

Catalogo Libreria Que Leo

CATALOGO LIBRERIA QUE LEO CodBarras Clasificacion Autor Titulo Libro Editorial Precio 9789569703126 AGENDA CAMILA LEON PLANNER - DIBUJA Y COLOREA TU SEMANA VASALISA 7,900 9789569703133 AGENDA FRAN MENESES FRANNERD PLANNER VASALISA 10,900 8437018304158 AGENDA N N AGENDA 2020 - ALICIA EN EL PAIS DE LAS ALMA 10,000 8437018304103 AGENDA N N AGENDA 2020 - ANNA KARENINA ALMA 10,000 8437018304141 AGENDA N N AGENDA 2020 - CONTIGO LA VIDA ES MAGIC ALMA 10,000 8437018304097 AGENDA N N AGENDA 2020 - CUMBRES BORRASCOSAS ALMA 10,000 8437018304127 AGENDA N N AGENDA 2020 - EL PLACER DE LEER ALMA 10,000 8437018304172 AGENDA N N AGENDA 2020 - GATOS ALMA 10,000 8437018304165 AGENDA N N AGENDA 2020 - MANDALAS ARTE TERAPIA ALMA 10,000 8437018304196 AGENDA N N AGENDA 2020 - SERENIDAD ALMA 10,000 7798083705778 AGENDA N N AGENDA MIA 2020 VR 6,000 7798083705747 AGENDA N N AGENDA SOLO PARA CHICAS 2020 (FIGURAS VR 5,000 7798083705754 AGENDA N N AGENDA SOLO PARA CHICAS 2020 (PLANETAS VR 5,000 1433092290001 AGENDA N N LIBRETA LA HERENCIA PRESENTE - VARIEDA LA HERENCIA PRESEN 3,500 9789789879878 AGENDA N N STICKERS ESCRITORES BICI LAKOMUNA 2,500 9789569703188 AGENDA N.N PLANNER JARDIN DE MEDIANOCHE VASALISA 12,900 9789569703157 AGENDA SOL DIAZ ELEGANTES PLANIFICADAS VASALISA 7,900 9789563603965 ANIMALES CARLA INGUS MARIN GUIA DEL PERRO MESTIZO CHILENO PLANETA 13,500 9789569960017 ANIMALES N N PAJAREANDO - AVES DE JARDINES Y CERROS ILUSTRAVERDE 11,500 9789561604575 ANTROPOLOGIA ANDRES DONOSO ROMOEDUCACION Y NACION AL SUR DE LA FRONTE PEHUEN 8,000 9789561124844 ANTROPOLOGIA BERNARDO ARRIAZA CULTURA CHINCHORRO UNIVERSITARIA 16,500 9789681609337 ANTROPOLOGIA C. -

Corporación De Ayuda Al Niño Quemado

CORPORACIÓN DE AYUDA AL NIÑO QUEMADO COANIQUEM MEMORIA 2018 2 INDICE I Antecedentes de la Corporación de Ayuda al Niño Quemado Pag. 4 II Centro de Rehabilitación del Niño Quemado de Santiago Pag.14 III Centro de Rehabilitación del Niño Quemado de Antofagasta Pag.23 IV Centro de Rehabilitación del Niño Quemado de Puerto Montt Pag.25 V Casabierta Pag.27 VI Gerencia General Pag.40 VII Dirección de Extensión, Docencia e Investigación Pag.42 VIII Fiscalía Pag.54 IX Comité de Ética Científica (CEC) Pag.55 X Comité de Ética Asistencial (CEA) Pag.56 XI Santuario de Cristo Flagelado y Confraternidad Pag.57 XII Instituciones Relacionadas Pag.64 XIII Presidencia Pag.68 Anexos Pag.72 3 C A P I T U L O I ANTECEDENTES DE LA CORPORACIÓN DE AYUDA AL NIÑO QUEMADO COANIQUEM La Corporación de Ayuda al Niño Quemado es una Institución de beneficencia sin fines de lucro, creada el 19 de abril de 1979 y dotada de personalidad jurídica por Decreto Supremo Nº 856 de 1980, del Ministerio de Justicia; sus actividades las desarrolla en forma totalmente gratuita para sus beneficiarios. Su finalidad puede extraerse del Artículo Segundo de sus estatutos que dice: "la Corporación mencionada tiene por objeto principal: proporcionar ayuda material, médica, psicológica, educacional y espiritual a niños y adolescentes de escasos recursos económicos que sufran lesiones de quemaduras o de otras patologías similares. Para el cumplimiento de dicho objetivo principal la Corporación podrá: 1) Realizar programas de acción social y educacional en todos sus niveles y modalidades en beneficio de niños y adolescentes que sufrieren quemaduras u otras patologías similares. -

Ford Foundation Annual Report 2000 Ford Foundation Annual Report 2000 October 1, 1999 to September 30, 2000

Ford Foundation Annual Report 2000 Ford Foundation Annual Report 2000 October 1, 1999 to September 30, 2000 Ford Foundation Offices Inside front cover 1 Mission Statement 3 President’s Message 14 Board of Trustees 14 Officers 15 Committees of the Board 16 Staff 20 Program Approvals 21 Asset Building and Community Development 43 Peace and Social Justice 59 Education, Media, Arts and Culture 77 Grants and Projects, Fiscal Year 2000 Asset Building and Community Development Economic Development 78 Community and Resource Development 85 Human Development and Reproductive Health 97 Program-Related Investments 107 Peace and Social Justice Human Rights and International Cooperation 108 Governance and Civil Society 124 Education, Media, Arts and Culture Education, Knowledge and Religion 138 Media, Arts and Culture 147 Foundationwide Actions 155 Good Neighbor Grants 156 157 Financial Review 173 Index Communications Back cover flap Guidelines for Grant Seekers Inside back cover flap Library of Congress Card Number 52-43167 ISSN: 0071-7274 April 2001 Ford Foundation Offices • MOSCOW { NEW YORK BEIJING • NEW DELHI • • MEXICO CITY • CAIRO • HANOI • MANILA • LAGOS • NAIROBI • JAKARTA RIODEJANEIRO • • WINDHOEK • JOHANNESBURG SANTIAGO • United States Africa and Middle East West Africa The Philippines Andean Region Makati Central Post Office and Southern Cone Headquarters Eastern Africa Nigeria P.O. Box 1936 320 East 43rd Street P.O. Box 2368 Chile Kenya 1259 Makati City New York, New York Lagos, Nigeria Avenida Ricardo Lyon 806 P.O. Box 41081 The Philippines 10017 Providencia Nairobi, Republic of Kenya Asia Vietnam Santiago 6650429, Chile 340 Ba Trieu Street Middle East and North Africa China Hanoi, Socialist Republic International Club Office Building Russia Egypt of Vietnam Suite 501 Tverskaya Ulitsa 16/2 P.O. -

Narrow but Endlessly Deep: the Struggle for Memorialisation in Chile Since the Transition to Democracy

NARROW BUT ENDLESSLY DEEP THE STRUGGLE FOR MEMORIALISATION IN CHILE SINCE THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY NARROW BUT ENDLESSLY DEEP THE STRUGGLE FOR MEMORIALISATION IN CHILE SINCE THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY PETER READ & MARIVIC WYNDHAM Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Read, Peter, 1945- author. Title: Narrow but endlessly deep : the struggle for memorialisation in Chile since the transition to democracy / Peter Read ; Marivic Wyndham. ISBN: 9781760460211 (paperback) 9781760460228 (ebook) Subjects: Memorialization--Chile. Collective memory--Chile. Chile--Politics and government--1973-1988. Chile--Politics and government--1988- Chile--History--1988- Other Creators/Contributors: Wyndham, Marivic, author. Dewey Number: 983.066 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: The alarm clock, smashed at 14 minutes to 11, symbolises the anguish felt by Michele Drouilly Yurich over the unresolved disappearance of her sister Jacqueline in 1974. This edition © 2016 ANU Press I don’t care for adulation or so that strangers may weep. I sing for a far strip of country narrow but endlessly deep. No las lisonjas fugaces ni las famas extranjeras sino el canto de una lonja hasta el fondo de la tierra.1 1 Victor Jara, ‘Manifiesto’, tr. Bruce Springsteen,The Nation, 2013. -

Revistas Contraculturales En Chile: De La Resistencia a La Transición (1983-1991)

UNIVERSIDAD ACADEMIA DE HUMANISMO CRISTIANO ESCUELA DE PERIODISMO ÁREA DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Revistas contraculturales en Chile: De la resistencia a la transición (1983-1991) Nombre: Carolina Sánchez Carvajal Profesor guía: Raúl Rodríguez Agosto 2013 1 Agradecimientos La presente Tesis es un esfuerzo en el cual, directa o indirectamente, participaron varias personas leyendo, opinando, corrigiendo, teniéndome paciencia, dando ánimo, acompañando en los momentos de crisis y en los momentos de felicidad. Gran parte de estas personas son mi familia, ellos fueron los que con su apoyo y aguante estuvieron a mi lado en cada momento del largo camino que significó armar este proyecto. Para cada uno mi más enorme agradecimiento. A mi madre pilar fundamental de mi vida, gracias por enseñarme a ser perseverante y luchadora, a tener coraje y ser una mejor persona. Sin tu ayuda nada de esto sería posible. A mi padre y hermanos que a pesar de la distancia siempre los llevo en mi corazón y pensamientos, son la fuerza que desde lejos me impulsa cada día a levantarme. Gracias por estar siempre presente en mi vida. Al amor de mi vida, compañera de mis grandes sueños y anhelos, has sido la encargada de darme aliento a cada momento. Gracias por el apoyo incondicional y por ayudarme a no bajar los brazos. A Robert por brindarme su cariño y amor. Nunca olvidaré tus consejos y enseñanzas. Eres una persona muy importante para mí, espero siempre tenerte a mi lado. Agradezco también a todas las personas que colaboraron con esta investigación. Los entrevistados por su interés y aporte en el proyecto. -

La Cotidianidad Desde Una Perspectiva Femenina En Dos Libros De Relatos Breves De Dos Autoras Chilenas

Universiteit Gent Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Taal - en Letterkunde: Frans - Spaans Academiejaar 2012 – 2013 La cotidianidad desde una perspectiva femenina en dos libros de relatos breves de dos autoras chilenas: (Des)encuentros (des)esperados y No decir de Andrea Maturana Últimos fuegos y Animales domésticos de Alejandra Costamagna Masterscriptie ingediend tot het behalen Promotor: van de graad Master in de Taal- en Profa. dra. Ilse Logie Letterkunde: Frans - Spaans door Goedele Verburgh 2 Agradecimientos Quiero dar las gracias a mi tutora, la profesora Ilse Logie, que me apoyó durante el proceso de escribir esta tesina, dando consejos útiles y revisando el texto. También quiero agradecer a la profesora Bieke Willem, por ayudarme a definir el tema de este trabajo, lo que era un obstáculo al inicio. Por último, también han sido muy importantes mi familia y mis amigos, que me apoyaron mentalmente, por lo que quiero agradecerles. 3 Índice 0) Índice ...................................................................................................................................... 4 1) Introducción ........................................................................................................................... 6 I) MARCO TEÓRICO 2) Inscripción en el género del cuento ...................................................................................... 8 2.1 Críticos: Mario Vargas Llosa y Camilo Marks ........................................................................ 8 2.2 cl., Textos de Frontera ........................................................................................................... -

Guía Eclesiástica De La Arquidiócesis De Santiago - 2

ARZOBISPADO DE SANTIAGO CHILE Guía Eclesiástica de la Arquidiócesis de Santiago - 2 - ______________________________________________________________________ Arquidiócesis de Santiago ______________________________________________________________________ I) Datos Generales La Diócesis fue creada por el Papa Pío V el 27 de junio de 1561 siendo su primer Obispo D. Rodrigo González Marmolejo. En 1840 fue elevada al rango de Arquidiócesis y su primer Arzobispo fue D. Manuel Vicuña Larraín quien falleció tres años más tarde. Le sucedieron: D. Rafael Valentín Valdivieso Zañartu (1847-1878), D. Joaquín Larraín Gandarillas como Vicario Capitular (1878-1886), D. Mariano Casanova Casanova (1886-1908), D. Juan Ignacio González Eyzaguirre (1908-1918), D. Crescente Errázuriz Valdivieso (1918-1931), D. José Horacio Campillo Infante (1931-1939), D. José María Caro Rodríguez, quien fue el primer Cardenal chileno (1939-1959), D. Emilio Tagle Covarrubias como Administrador Apostólico (1959-1961), D. Raúl Silva Henríquez, Cardenal (1961-1982), D. Juan Francisco Fresno Larraín, Cardenal (1982-1990), D. Carlos Oviedo Cavada, Cardenal (1990-1998) y D. Francisco Javier Errázuriz Ossa, Cardenal y actualmente, Mons. Ricardo Ezzati Andrello, desde el 15 de diciembre de 2010. Titular: Apóstol Santiago Superficie: 9.202 km2 Población: 6.089.516, dentro de los cuales hay 3.981.790 de fieles católicos (65%) Parroquias: 216 Presbíteros: La Arquidiócesis cuenta con la colaboración de: --------------------------------------------- Guía Eclesiástica de Santiago Santiago de Chile, al 8 de octubre de 2018 - 3 - - 229 Sacerdotes Incardinados en Santiago - 67 Sacerdotes Incardinados en Otras Diócesis - 147 Párrocos Diocesanos - 68 Párrocos Religiosos Diáconos Permanentes: 393 --------------------------------------------- Guía Eclesiástica de Santiago Santiago de Chile, al 8 de octubre de 2018 - 4 - ______________________________________________________________________ II) Gobierno Eclesiástico Sr. -

Reflexiones En Torno a La Reforma Educacional Desde Una Perspectiva Católica1

REFLEXIONES EN TORNO A LA REFORMA EDUCACIONAL DESDE UNA PERSPECTIVA CATÓLICA1 Jaime Caiceo Escudero2 Universidad de Santiago de Chile, [email protected] RESUMEN: Con una visión histórica y educativa de la educación chilena en general, y de la educación católica en particular, se demuestra en una primera etapa el rol preponderante que la Iglesia Católica ha tenido en la historia educacional de Chile, tanto a nivel universitario como escolar: en la colonia desde la llegada de las primeras congregaciones ellas tuvieron un rol casi exclusivo; en la república, las escuelas parroquiales jugaron un papel trascendente por 150 años. Se analiza el aporte que las distintas congregaciones han realizado a la educación con colegios gratuitos para los más necesitados y también con establecimientos pagados para formar a las élites. La Universidad Católica de Chile, a su vez, ha sido muy importante para desarrollar la ciencia en concordancia con la filosofía y la teología. Con ello se pretende demostrar que la Iglesia Católica tiene autoridad moral en Chile para opinar y actuar en educación. La descripción considera elementos de filosofía cristiana y doctrina social de la Iglesia. En una segunda etapa se analiza la reforma educacional iniciada en el 2015 en el país, enfatizando que es necesario asumirla con los desafíos que ella implica, especialmente con la ley de inclusión que plantea fin al financiamiento compartido, fin a la selección y fin al lucro. Palabras-clave: Historia de la Educación. Reforma educacional. Educación católica. Escuela católica. 1 Este artículo se basa en una reflexión que se realizó el 20 de abril de 2016. -

01 Corpo Da Revista No Template

RESUM0 LA MUSICA PARA CLARA [A MÚSICA A resenha aqui apresentada remete ao livro PARA CLARA]: La música para Clara [A música para Clara], da autora chilena Elizabeth Subercaseaux. Lançada em 2014, a biografia romanceada da RESENHA DO LIVRO DE ELIZABETH compositora alemã Clara Schumann (1819- SUBERCASEAUX 1896) tem como diferencial o tom intimista adotado pela autora, que é tataraneta de Clara e Robert Schumann, descendente, RevistaMúsica | vol. 19, n.2 | portanto, do casal que marcou a História da pp. 279-288 | jul. 2019 Música Ocidental por suas contribuições ao estilo romântico que vigorou no século XIX. Amilcar Zani PALAVRAS-CHAVE: [email protected] | USP Resenha; Clara Schumann (1819-1896); Heloísa Fortes Zani Elizabeth Subercaseaux. [email protected] | USP Eliana Monteiro da Silva [email protected] | USP ABSTRACT The present review refers to the book La música para Clara [The music for Clara], written by the Chilean author Elizabeth Subercaseaux. Launched in 2014, the biography of the German composer Clara Schumann (1819-1896) has as a differential issue the intimate touch adopted by the author, who is Clara and Robert Schumann's great-great-granddaughter. The couple is acknowledged for their contributions to the LA MUSICA PARA CLARA romantic style that came to light in the [THE MUSIC FOR CLARA]: nineteenth century, stamping their mark in ELIZABETH the Western Music’s History. SUBERCASEAUX’S BOOK REVIEW KEYWORDS: Recebido em: 13/05/2019 Review; Clara Schumann (1819-1896); Elizabeth Subercaseaux. Aprovado em: 02/06/2019 revistamúsica | vol. 19, n.1 | julho de 2019 LA MUSICA PARA CLARA [A MÚSICA PARA CLARA]: RESENHA DO LIVRO DE ELIZABETH SUBERCASEAUX Amilcar Zani [email protected] | USP Heloísa Fortes Zani [email protected] | USP Eliana Monteiro da Silva [email protected] | USP I. -

The Catholic Church and Populist Leadership in Juan Perón's

Collecting Consciences: The Catholic Church and Populist Leadership in Juan Perón’s Argentina and Salvador Allende’s Chile A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Renée Crown University Honors Program at Syracuse University Emma Louise Fountain Candidate for Bachelor of Arts and Renée Crown University Honors Spring 2020 Honors Thesis in International Relations Thesis Advisor: _______________________ Dr. Gladys McCormick Thesis Reader: _______________________ Dr. Francine D’Amico Honors Director: _______________________ Dr. Karen Hall Fountain 2 Abstract This paper identifies populism’s key actors and addresses three essential relationships. These actors are the political leader (the president), the religious leader (the Catholic Church), and the led (the people). The relationships examined here are those between the political leader and the led, the political and the religious leaders, and the religious leader and the led. This framework is then applied to the distinctly populist presidencies of Juan Perón in Argentina and Salvador Allende in Chile. Evidence for these cases comes from an assortment of sources, from contemporary accounts of leadership to recent reflections. Perón began his regime in 1946 with strong relationships on every front, but lost the support of the Catholic Church and subsequently the support of the people by the mid-1950s. Allende’s populism was a development of Perón’s populism. In the two decades that separated the Argentine leader from the Chilean, an activist movement within the Christian community undermined the Catholic Church’s political pull. Therefore, Allende’s weak relationship with the Church and powerful link to the people was politically successful. This comparison of Perón and Allende offers valuable insight on the viability of different modes of populism.