Defining Russian Sacred Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific Southern Chapter the COLLEGE MUSIC SOCIETY

Pacific Southern Chapter THE COLLEGE MUSIC SOCIETY 20th Regional Conference March 17–18, 2006 California State University – Los Angeles Los Angeles, California Pacific Southern Chapter THE COLLEGE MUSIC SOCIETY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The CMS Pacific Southern Chapter gratefully acknowledges all of those who have worked tirelessly to make this conference such a tremendous success: David Connors, Chair, Cal State L.A. Department of Music John M. Kennedy, Director, Cal State L.A. New Music Ensemble and Program co-chair Cathy Benedict, Program co-chair CMS Pacific Southern Chapter Executive Board President: Jeffrey Benedict (California State University - Los Angeles) Vice-President: Cathy Benedict (New York University) Treasurer: William Belan (California State University - Los Angeles) Secretary: Elizabeth Sellers (California State University - Northridge) CMS Pacific Southern Chapter Conference Committee John Kennedy Cathy Kassell Benedict Jeff Benedict March 17, 2006 Dear CMS Colleagues: On behalf of my colleagues at the California State University, Los Angeles, I would like to welcome you to the 2006 College Music Society Southern Pacific Chapter Conference. As always, we have an exciting slate of performances and presentations, and I am sure it will prove to be an intellectually stimulating event for all of us. I look forward to the free exchange of ideas that has become the hallmark of our chapter conferences. I would especially like to welcome Dr. Andrew Meade, who has graciously accepted our invitation to be the keynote speaker. Again, welcome, and I hope that you all have a fabulous conference her at Cal State L.A. Jeff Benedict CMS Pacific-Southern Chapter President 2006 Conference Host S TEINWAY IS THE OFFICIAL PIANO of THE COLLEGE MUSIC SOCIETY’S NATIONAL CONFERENCE New from2 Forthcoming! BEYOND TALENT RESEARCHING THE SONG Creating a Successful Career in Music A Lexicon ANGELA MYLES BEECHING SHIRLEE EMMONS and WILBUR WATKINS LEWIS, Jr. -

Changing Cultural Paradigms in Choral Programming

Changing Cultural Paradigms in Choral Programming Ciara Anwen Cheli Advisor: Lisa Evelyn Graham, Music Wellesley College May 2020 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Music © Ciara Cheli, 2020 Cheli 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Part One: Reflecting on Our Past ................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One: An Overview of Choral Programming and Historical Trends ........................................... 7 Chapter Two: Modernism and a Choral Identity Crisis ......................................................................... 10 Chapter Three: Historical Perspectives on Concert Programming and Repertoire .............................. 15 Part Two: Looking To Our Future ................................................................................................ 19 Chapter One: Changing Cultures, Changing Choirs ............................................................................. 19 Chapter Two: Representation Matters .................................................................................................... 20 Chapter Three: Culturally Responsive Programming in the 21st Century .............................................. 24 Chapter Four: -

Number Composer Arranger Title Publisher Instrumentation Inventory 504 Don't Sit Under the Apple Tree MS 9 651 Carols for Choirs

number composer arranger title publisher instrumentation inventory 504 Don't sit under the apple tree MS 9 Oxford 651 Carols for choirs 3. The Oxford Book - SATB 13 University Press Oxford 650 Carols for choirs 1,The Oxford Book - SATB 140 University Press Paulus 957 Pilgrims' Hymn (from the Church Opera The Three Hermits) Publications SATB a cappella 56 SP101 Jenson Distinctive 647h Dale Warland Christmas editions, Vol. II Publications 419- accompaniment 57 23054/Vol II s 73 Adamo, Mark Supreme Virtue, No. 10 MS - 1 copy only Double choir 1 906 Aguiar, Ernani Psalm 150 (Salmo 150) earthsongs SATB a cappella 54 983 Albright, William Chichester Mass (Agnus Dei, Gloria, Kyrie, Sanctus) Editions Peters SATB 43 Walton Music Corporation WGK-111; AB 26 Alfven, Hugo Maiden is in a Ring, A (Och jungfrun hon gar I ringen) SATB a cappella 37 Carl Gehrmans Musikforlag. Stockholm 55 Alfven, Hugo Aftonen Walton Music 51 Augsburg 382 Alwes, Chester Let all the people praise thee SATB 8 Publishing 358 Anonymous Verbum caro: dies est laetitiae MS 44 357 Anonymous Nova, nova MS 46 399 Anonymous Ave maria (Gregorian chant) MS SATB 17 Boosey & SATB, 172 Argento, Dominick I Hate and I Love 51 Hawkes percussion SATB, Boosey & 847 Argento, Dominick Toccata of Galuppi's, A harpsichord, 41 Hawkes string quartet Boosey & 239 Argento, Dominick Peter Quince at the clavier SATB, piano 40 Hawkes Boosey & 480 Argento, Dominick Gloria (from The Masque of Angels) SATB 96 Hawkes Boosey & SSA Harp and 63 Argento, Dominick Tria Carmina Paschalia Hawkes B.H. Bk. 21 Guitar -

Cornerstones of the Ukrainian Violin Repertoire 1870 – Present Day

Cornerstones of the Ukrainian violin repertoire 1870 – present day Carissa Klopoushak Schulich School of Music McGill University Montreal, Quebec January 2013 A doctoral paper submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Music in Performance Studies © Carissa Klopoushak 2013 i Abstract: The unique violin repertoire by Ukrainian composers is largely unknown to the rest of the world. Despite cultural and political oppression, Ukraine experienced periods of artistic flurry, notably in the 1920s and the post-Khrushchev “Thaw” of the 1960s. During these exciting and experimental times, a greater number of substantial works for violin began to appear. The purpose of the paper is one of recovery, showcasing the cornerstone works of the Ukrainian violin repertoire. An exhaustive history of this repertoire does not yet exist in any language; this is the first resource in English on the topic. This paper aims to fill a void in current scholarship by recovering this substantial but neglected body of works for the violin, through detailed discussion and analysis of selected foundational works of the Ukrainian violin repertoire. Focusing on Maxym Berezovs´kyj, Mykola Lysenko, Borys Lyatoshyns´kyj, Valentyn Sil´vestrov, and Myroslav Skoryk, I will discuss each composer's life, oeuvre at large, and influences, followed by an in-depth discussion of his specific cornerstone work or works. I will also include cultural, musicological, and political context when applicable. Each chapter will conclude with a discussion of the reception history of the work or works in question and the influence of the composer on the development of violin writing in Ukraine. -

1 May 2015 Page 1 of 19

Radio 3 Listings for 25 April – 1 May 2015 Page 1 of 19 SATURDAY 25 APRIL 2015 Valentina Reshetar (soprano), Irina Horlytska (contralto), Vasyl Kovalenko (tenor), Oleksandr Bojko (bass) Platon Maiborada SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b05qz0cd) Academic Choir, Viktor Skoromny (conductor) Il Giardino Armonico - Vivaldi and Castello 4:25 AM Il Giardino Armonico and director Giovanni Antonini perform Sibelius, Jean (1865-1957) works by Vivaldi and Castello. Catriona Young presents. Romance for violin and piano (Op.78 No.2); Rondine (Op.81 No.2) 1:01 AM Reka Szilvay (violin), Naoko Ichihashi (piano) Castello, Dario (fl.1621-1629) Sonata no. 10, from 'Sonate concertate in stil moderno, Book II' 4:30 AM Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni Antonini (director) Janequin, Clément (c. 1485-1558) Crecquillon, Thomas (c.1505/15-1557) 1:10 AM Sermisy, Claudin de (c.1490-1562) Castello Four Renaissance Chansons Sonata no. 12, from 'Sonate concertate in stil moderno, Book II' Vancouver Chamber Choir, Ray Nurse (lute, guitar, viol), Nan Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni Antonini (director) Mackie & Patricia Unruh (viols), Magriet Tindemans (viol/recorder), Liz Baker (recorder), Jon Washburn (director) 1:17 AM Vivaldi, Antonio (1678-1741) 4:42 AM Concerto in G minor RV.104 (La Notte) for flute (or violin), 2 Geminiani, Francesco (1687-1762) vlns, bassoon & bc Concerto No.1 in D major, Op.7 No.1 (1746) Giovanni Antonini (flute/director), Il Giardino Armonico Academy of Ancient Music, Andrew Manze (director/violin) 1:27 AM 4:51 AM Vivaldi Novacek, Ottokar Eugen (1866-1900) Trio sonata in D minor RV.63, Op.1'12 (La Follia) for 2 violins Perpetuum Mobile and continuo Moshe Hammer (violin), Valerie Tryon (piano) Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni Antonini (director) 4:53 AM 1:37 AM Goens, Daniel van (1858-1904) Scarlatti, Alessandro (1660-1725) Scherzo Sonata no. -

3 July 2015 Page 1 of 10

Radio 3 Listings for 27 June – 3 July 2015 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 27 JUNE 2015 Ashley Wass (piano) SAT 12:15 Music Matters (b060bfm1) Gunther Schuller 1925-2015, Damiano Michieletto, Alex Poots SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b05zhc6l) 5:12 AM - MIF 2014 Chopin and His Europe International Music Festival Poulenc, Francis (1899-1963) (orch. Sir Lennox Berkeley) Flute Sonata (1956) Tom Service pays tribute to the American composer, conductor Jonathan Swain presents a concert from the 2014 "Chopin and Emmanuel Pahud (flute), Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, and performer Gunther Schuller, talks to opera director his Europe" International Music Festival. Enrique Garcia-Asensio (conductor) Damiano Michieletto and meets the outgoing director of the Manchester International Festival, Alex Poots. 1:01 AM 5:25 AM Panufnik, Andrzej (1914-1991) Berkeley, Lennox [1903-1989] / Auden, WH. [1907-1973] Train of Thoughts - string sextet Lay your sleeping head, my love (Op.14, No.2b) SAT 13:00 Radio 3 Lunchtime Concert (b060bfm3) Lena Neudauer (violin), Erzhan Kulibaev (violin), Katarzyna Robin Tritschler (tenor), Malcolm Martineau (piano) Max Emanuel Cencic and Pomo d'Oro Budnik-Galazka (viola), Artur Rozmyslowicz (viola), Marcin Zdunik (cello), Rafal Kwiatkowski (cello) 5:32 AM The Croatian-born countertenor Max Emanuel Cencic teams up Bach, Johann Sebastian (1685-1750) / Gounod, Charles with the ensemble Pomo d'oro to perform Baroque Italian 1:16 AM (1818-1893) music including works by Vivaldi, Albinoni, Gasparini and Krogulski, Józef (1815-1842) Meditation -

19 April 2019 Page 1 of 20

Radio 3 Listings for 13 – 19 April 2019 Page 1 of 20 SATURDAY 13 APRIL 2019 04:31 AM Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) SAT 00:30 Music Planet World Mix (m00041gw) Litanies à la Vierge Noire version for women's voices and organ Psychebelly Dance and the Godfather of Nubian Soul (1936) La Gioia, Diane Verdoodt (soprano), Ilse Schelfhout (soprano), Global beats and roots music from every corner of the world - Kristien Vercammen (soprano), Bernadette De Wilde (soprano), including 'Psychebelly Dance Music' from Turkish band Baba Lieve Mertens (mezzo soprano), Els Van Attenhoven (mezzo Zula; the "Godfather" of Nubian music, Ali Hassan Kuban; the soprano), Peter Thomas (organ) latest sounds from Kinshasa; and a traditional Italian song by Canzoniere Grecanico Salentino. 04:40 AM August de Boeck (1865-1937) Nocturne (1931) SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m00041gy) Vlaams Radio Orkest [Flemish Radio Orchestra], Marc Soustrot String Quartets from Bucharest (conductor) Arcadia Quartet perform Haydn, Shostakovich and Beethoven. 04:50 AM Jonathan Swain presents. Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Slavonic March in B flat minor 'March Slave' 01:01 AM BBC Philharmonic, Rumon Gamba (conductor) Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) String Quartet No 30 in E flat Op 33'2 Hob. iii:38 'Joke' 05:01 AM Arcadia Quartet Bongani Ndodana-Breen (b.1975) Harmonia Ubuntu 01:16 AM Goitsemang Oniccah Lehobye (soprano), Minnesota Orchestra, Dmitry Shostakovich (1906-1975) Osmo Vänskä (conductor) String Quartet No 8 in C minor Op 110 Arcadia String Quartet 05:11 AM Johann Jacob de Neufville -

Professor Marina Ritzarev Principal Associate Researcher

Professor Marina Ritzarev Principal Associate Researcher Education MA – 1969, St. Petersburg Conservatory PhD – 1973, St. Petersburg Conservatory Dr. Habil. – 1989, Kiev Conservatory Fields of research Eighteenth-century Russian music, Choral concerto, Dmitry Bortniansky, Maxim Berezovsky, Russian musical culture in general, Tchaikovsky, Soviet music, Sergei Slonimsky, Shostakovich, Vernacularity and nationalism in music, Music in immigrant communities, Jewish music, Josef Bardanashvili, Musical significations, Textbook sonata form and Propp's morphology of fairy tale. Publications Books Dmitry Bortniansky and His Time. 2nd edition, revised and enlarged. [In Russian]. St. Petersburg, Compozitor. Forthcoming. The Composer Maxim Berezovsky. 2nd edition, revised and enlarged. [In Russian]. St. Petersburg, Compozitor. In press. (As editor) Garment and Core: Jews and their Musical Experiences, Eds. E. Avitsur, M. Ritzarev, E. Seroussi. Bar-Ilan University Press. 2012. Eighteenth-Century Russian Music. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006. Sacred Concerto in Russia of the Late Eighteenth Century [in Russian]. St. Petersburg: Compozitor, 2006. The Composer Sergei Slonimsky [in Russian]. St. Petersburg: Sovetskiy Kompozitor, 1991. Russian Music of the 18th Century [in Russian]. Moscow: Znanie, 1987. The Composer M. S. Berezovsky [in Russian]. St. Petersburg: Muzyka, 1983. The Composer D. Bortniansky [in Russian]. St. Petersburg: Muzyka, 1979. Reference books The Israeli Music Archive: List of Collections. Tel-Aviv: Tel-Aviv University, 1998. Music and Me - popular encyclopedia for youth [in Russian]. Moscow: Muzyka, 2006 (4th ed., 2000, 1998, 1994). Rachmaninoff’s Autographs in the Archives of the State Central Glinka Museum of Musical Culture [in Russian]. Moscow: Sovetskiy Kompozitor, 1980. Articles and chapters in books “One personality and several identities of the émigré composer Josef Bardanashvili”, in Composer and his Environment, Ed. -

Dale Warland Singers, 2000-2001 Season, February 17, Ted Mann

f[fji~~~ -------------------------------- HIGHLIGHTS OF OUR UPCOMING SEASON 2001-2002 Saturday, October 27, 200 1 Ted Mann Concert Hall A melting pot of American Music including folksongs, Native American Songs, Chinese-American music, spirituals, hymns and a little bit of jazz. Saturday, February 9, 2002 Benson Great Hall, Bethel College Three high school chamber choirs join the Dale Warland Singers in a program of international music. Saturday, March 9, 2002 Basilica of Saint Mary Hear the luscious sounds of the Dale Warland Singers in this magnificent cathedral setting- reflective, inspirational and contemplative. Saturday, April 20, 2002 Ted Mann Concert Hall Ballads and songs-by Argento, Brittten and others. JOIN US FOR OUR HOLIDAY CONCERTS: Echoes of Christmas Christmas carols-some old and some new. Home for the Holidays Friday, December 7, 200 1 Saturday, December 8, 2001 Sunday, December 9, 2001 A one-hour holiday favorite-especially for families and children. LOOK FOR OUR SEASON BROCHURE IN APRII:!-~ ________________ l~~~R:-- TABLE OF CONTENTS Program Book II January-May 200 1 The Dale Warland Singers .3 About Dale Warland ." .4 Artistic Staff .s Members of the Dale Warland Singers 6 Board of Directors and Staff 7 Executive Director's Message 8 The Italian Connection program 9 Cathedral Classics program .16 Songs of the Earth program 20 New Choral Music Program 25 Singer Biographies 26 Dale Warland Singers Recordings .30 Contributors .31 Acknowledgements .34 2 jijE~~1-.~ ------------------------------------ THE DALE WARLAND SINGERS Now in its twenty-ninth season of concerts, tours, Radio International's Saint Paul Sunday. The annual Echoes radio broadcasts, and critically acclaimed recordings, the Dale of Christmas and Cathedral Classics broadcasts reach listeners Warland Singers is recognized as one of the world's foremost nationwide. -

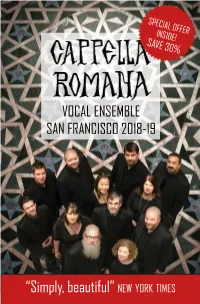

New York Times

SPECIAL OFFER INSIDE! SAVE 30% VOCAL ENSEMBLE SAN FRANCISCO 2018-19 “Simply, beautiful” NEW YORK TIMES 2018-19 San Francisco Series “Simply, beautiful” Cappella Romana has received extraordinary NEW YORK TIMES acclaim on national and international tours and in its Northwest series for over 27 years. We’re now pleased to launch a new “a sensual experience subscription series in San Francisco, meant to induce especially after the warm welcome from Bay a transcendent state” Area audiences like you in January 2018. SAN FRANCISCO You’ll have musical experiences with Cappella CLASSICAL VOICE Romana that are truly transformative. Rooted in the music of Old Rome (the West) and New Rome (Constantinople and the East), Cappella “innovative and Romana forges passion and scholarship into thought-provoking” music that keeps audiences coming back SEATTLE TIMES for more. I hope you’ll join us in October, January, “the finest and May, and we’ve put together a special scholarship aligned introductory offer for you to help make with artistry of that happen. the highest order” Save 30% on ticket prices when you FANFARE subscribe to all three concerts! I can’t wait to share this exciting new series with you. You’re going to love it! “jewel-like brilliance” GRAMOPHONE See you there! “this music is Mark Powell a living tradition” Executive Director NPR Series made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts SATURDAY 29 SEPTEMBER 2018 8:00PM ST. IGNATIUS CHURCH SAN FRANCISCO The Rachmaninoff “Vespers” Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil as you’ve never heard it before! A more complete Vigil with psalms and hymns by composers who paved the way for Rachmaninoff’s extraordinary achievement. -

ALFRED SCHNITTKE Choir Concerto Three Sacred Hymns

ALFRED SCHNITTKE Choir Concerto Three Sacred Hymns ARVO PÄRT Seven Magnificat- Antiphons Estonian Philharmonic ChamBer Choir Arvo Pärt and Alfred Schnittke in 1980, photographed by Nora Pärt. Kaspars PutniNš Courtesy of the Arvo Pärt Centre. Cover image: Father in prayer by Edvard Munch, 1902. Woodcut on paper, 51 x 37 cm BIS-2521 SCHNITTKE, Alfred (1934—98) Concerto for Choir (1984—85) (Sikorski) 39'55 1 1. O Pavelitel’ sushcheva fsevo (O Master of all living) 15'20 2 2. Sabran’je pesen sikh, gde kazhdyj stikh (This collection of songs, where every verse…) 7'59 3 3. Fsem tem, kto vniknet fsushchnast’ 11'33 (To all who grasp the meaning) 4 4. Sej trud, shto natchinal ja supavan’jem 4'44 (Complete this work which I began in hope) Three Sacred Hymns for mixed choir (1984) (Sikorski) 6'21 5 1. Bogoroditse Devo, raduisia (Hail Mary, full of Grace) 1'33 6 2. Gospodi Isuse Khriste (Lord Jesus) 1'19 7 3. Otche nash (Our Father) 3'25 2 PÄRT, Arvo (b. 1935) Seven Magnificat-Antiphons (1988/1991) (Universal Edition) 13'12 for mixed choir (SATB) a cappella 8 O Weisheit 1'35 9 O Adonai 1'56 10 O Spross aus Isais Wurzel (attacca) 0'56 11 O Schlüssel Davids (attacca) 2'26 12 O Morgenstern 2'13 13 O König aller Völker 1'20 14 O Immanuel 2'30 TT: 60'22 Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir Kaspars Putniņš conductor 3 he religious music of Alfred Schnittke (1934–98) and Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) documents the resurgence of Christianity in the last decades of the Soviet TUnion. -

Eighteenth-Century Russian Music, by Marina Ritzarev. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006. 387 Pp. Marina Ritzarev Is Known Both to English

Min-Ad: Israel Studies in Musicology Online Reviews Eighteenth-Century Russian Music, by Marina Ritzarev. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006. 387 pp. Marina Ritzarev is known both to English and Russian scholars as one of the most insightful specialists in the music of eighteenth-century Russia. Her Eighteenth- Century Russian Music represents the first attempt, written and published in English, to comprehensively cover the “long eighteenth century” of musical life in Russia. Ritzarev’s works in general represent a fortuitous combination of formidable archival study (during her career in Moscow and St. Petersburg, she enjoyed unlimited access to many unique materials and documents) with a robust conceptualization of data within a broad historical prospective. Ritzarev is the pre-eminent authority on Russian church music of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, especially with regard to the sacred choral concerto (partes concerto) seen in works such as those of Maxim Berezovsky and his successors, Dmitry Bortniasky, Stepan Degtyarev, and Artemy Vedel (along with the attempts of Italians Baldassare Galuppi and Giuseppe Sarti to contribute to this genuine national tradition). Her two monographs and numerous articles published in the last quarter of the twentieth century in Russian (Kompositor D. Bortniansky, Leningrad: Musika, 1979; Kompositor M.S. Berezovsky, Leningrad: Musika, 1983) powerfully espouse this spiritually overwhelming yet still little known repertoire. In this book, Ritzarev meticulously reconstructs the complicated infrastructure of musical life in Russia in the epoch between the death of Peter the Great (1725) and the renunciation of Alexander I (1825). During this century, Russian musical life developed from near total political and socio-cultural isolation toward the gradual and inevitable convergence of the powerful Russian Empire with mainstream European society.