Changing Cultural Paradigms in Choral Programming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific Southern Chapter the COLLEGE MUSIC SOCIETY

Pacific Southern Chapter THE COLLEGE MUSIC SOCIETY 20th Regional Conference March 17–18, 2006 California State University – Los Angeles Los Angeles, California Pacific Southern Chapter THE COLLEGE MUSIC SOCIETY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The CMS Pacific Southern Chapter gratefully acknowledges all of those who have worked tirelessly to make this conference such a tremendous success: David Connors, Chair, Cal State L.A. Department of Music John M. Kennedy, Director, Cal State L.A. New Music Ensemble and Program co-chair Cathy Benedict, Program co-chair CMS Pacific Southern Chapter Executive Board President: Jeffrey Benedict (California State University - Los Angeles) Vice-President: Cathy Benedict (New York University) Treasurer: William Belan (California State University - Los Angeles) Secretary: Elizabeth Sellers (California State University - Northridge) CMS Pacific Southern Chapter Conference Committee John Kennedy Cathy Kassell Benedict Jeff Benedict March 17, 2006 Dear CMS Colleagues: On behalf of my colleagues at the California State University, Los Angeles, I would like to welcome you to the 2006 College Music Society Southern Pacific Chapter Conference. As always, we have an exciting slate of performances and presentations, and I am sure it will prove to be an intellectually stimulating event for all of us. I look forward to the free exchange of ideas that has become the hallmark of our chapter conferences. I would especially like to welcome Dr. Andrew Meade, who has graciously accepted our invitation to be the keynote speaker. Again, welcome, and I hope that you all have a fabulous conference her at Cal State L.A. Jeff Benedict CMS Pacific-Southern Chapter President 2006 Conference Host S TEINWAY IS THE OFFICIAL PIANO of THE COLLEGE MUSIC SOCIETY’S NATIONAL CONFERENCE New from2 Forthcoming! BEYOND TALENT RESEARCHING THE SONG Creating a Successful Career in Music A Lexicon ANGELA MYLES BEECHING SHIRLEE EMMONS and WILBUR WATKINS LEWIS, Jr. -

Department Historyrevised Copy

The Music Department of Wayne State University A History: 1994-2019 By Mary A. Wischusen, PhD To Wayne State University on its Sesquicentennial Year, To the Music Department on its Centennial Year, and To all WSU music faculty and students, past, present, and future. ii Contents Preface and Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………………...........v Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………………............................ix Dennis Tini, Chair: 1993-2005 …………………………………………………………………………….1 Faculty .…………………………………………………………………………..............................2 Staff ………………………………………………………………………………………………...7 Fundraising and Scholarships …………………………………………………................................7 Societies and Organizations ……………………………………………..........................................8 New Music Department Programs and Initiatives …………………………………………………9 Outreach and Recruitment Programs …………………………………………….……………….15 Collaborative Programs …………………………………………………………………………...18 Awards and Honors ……………………………………………………………………………….21 Other Noteworthy Concerts and Events …………………………………………………………..24 John Vander Weg, Chair: 2005-2013 ………………………………………………................................37 Faculty………………………………………………………………..............................................37 Staff …………………………………………………………………………………………….....39 Fundraising and Scholarships …………………………………………………..............................40 New Music Department Programs and Initiatives ……………………………………………..…41 Outreach and Recruitment Programs ……………………………………………………………..45 Collaborative Programs …………………………………………………………………………...47 Awards -

Proceedings 2020 International Summit Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association

Proceedings of the 2020 International Summit of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association – October 2 & 3, 2020 – Proceedings of the 2020 International Summit 1 Contents Academic Papers Presented at the 2020 International Summit of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association October 2-3, 2020 Papers are listed alphabetically by author. 4 Integrating Audio Branding into the Marketing 40 Literature, Lemonade, and DAMN.: A Historical Curriculum: A Model Perspective on Popular Music Awards (abstract only) David Allan, Saint Joseph’s University Jason Lee Guthrie, Clayton State University 8 The Crossover: Evaluating Mainstream Consumption 41 Preparing Global-Ready, and Interculturally of Urban Music Concerts (abstract only) Competent Graduates for the Music and Morgan M. Bryant, Saint Joseph’s University Entertainment Industries Eric Holt, Belmont University Kristina Kelman, Queensland University of Technology 10 The Musician’s Profit Umbrella™ and Women as 48 Summer Camp: Developing a Recruiting Hotbed That Musician-Entrepreneurs (abstract only) Teaches High School Students Music Production Fabiana Claure, University of North Texas Steven Potaczek, Samford University 11 Measuring Folk 52 Skip, Burn, Seek & Scratch: Young Adults’ Compact Michelle Conceison, Middle Tennessee State University Disc Usage Experiences in 2020 (abstract only, full 23 Tools of the Craft: The Value of Practicums in Arts article available in the 2020 MEIEA Journal https:// and Music Management doi.org/10.25101/20.4) Mehmet Dede, The Hartt School, University of Hartford Waleed Rashidi, California State University, Fullerton 27 Dude, Where’s Your Phone?: Live Event Experience 53 Legends and Legacy: Musical Tourism in Muscle in a Phone-Free Environment (abstract only) Shoals (abstract only) Matthew Dunn, University of South Carolina Christopher M. -

20 to 25 March Free Concert Programme Welcome Kathryn Mcdowell

LSO FUTURES 20 to 25 March Free concert programme Welcome Kathryn McDowell In the third event of the festival on Sunday 24 March, the LSO performs a unique concert, presenting music that spills off the concert stage, into the hall and out to the community beyond. We begin in the foyers with a performance of David Lang’s the public domain given by the London Symphony Chorus and singers from the local community. I would like to take the opportunity to offer a very warm welcome to all those who have joined us to participate in this project, which was developed in collaboration with Culture Mile. Continuing in the Barbican Hall, LSO Principal Guest Conductor François-Xavier Roth conducts the UK premiere of Philippe Manoury’s Ring with the Orchestra distributed elcome to LSO Futures, our triennial throughout all three levels of the concert festival of new and contemporary hall. The world premiere of Donghoon Shin’s music, which this year explores the Kafka’s Dream follows, a commission of the theme of ‘space’ over four boundary-pushing LSO’s Panufnik Composers Scheme, before events. The festival begins on Wednesday 20 Scriabin’s Symphony No 4, ‘Poem of Ecstasy’ March with Getting It Right? New Music/ closes the concert. New Technologies, a creative forum hosted by Guildhall School in collaboration with Monday 25 March brings LSO Futures to a LSO Discovery. The forum starts with a close as François-Xavier Roth joins us once sound installation devised by students more to lead a day of workshops at LSO from the Guildhall School’s Electronic Music St Luke’s. -

Human Requiem (U.S

Sunday, October 16, 2016, at 7:30 pm Tuesday–Wednesday, October 18–19, 2016, at 7:30 pm Post-performance discussion on Tuesday, October 18 with Simon Halsey, Jochen Sandig, and Patrick Castillo human requiem (U.S. premiere) Rundfunkchor Berlin Simon Halsey , Conductor Marlis Petersen , Soprano Konrad Jarnot , Baritone Angela Gassenhuber , Piano Philip Mayers , Piano Nicolas Fink , Co-Conductor Jochen Sandig , Concept and Scenic Realization Brad Hwang , Spatial Concept Jörg Bittner , Lighting BRAHMS Ein deutsches Requiem for soloists, chorus, and piano four hands (1868/2004) Arranged by Phillip Moll from the original transcription by Brahms Selig sind, die da Leid tragen Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras Herr, lehre doch mich Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit Denn wir haben hie keine bleibende Statt Selig sind die Toten This performance is approximately 70 minutes long without intermission. Please join the artists for a White Light Lounge immediately following the performance. These performances are made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano Please make certain all your electronic devices Synod House, are switched off. Cathedral of St. John the Divine WhiteLightFestival.org MetLife is the National Sponsor of Lincoln Center. UPCOMING WHITE LIGHT FESTIVAL EVENTS: Artist Catering provided by Zabar’s and Zabars.com Friday, October 21 at 7:30 pm in the Church of St. Mary the Virgin American Airlines is the Official Airline of Lincoln Immortal Bach Center Rundfunkchor Berlin -

4 Behind the Scenes Playing in Rep 6 Your Latest School News and Stories

The Guildhall School Magazine Spring/ Summer 2016 4 Behind the Scenes 26 The Interview Playing in Rep Athole Still 6 Your latest School 30 Then & Now news and stories Debbie Wiseman PLAY32 Class Notes 35 In Memoriam Sir George Martin 12 Guildhall to the World New York, New York 14 My Legacy Gift Kevin Webb 16 Where art meets business 22 Doctor in the House 38 A Day in the Life Philip Venables Sara Lee Editorial Group Welcome to the latest edition of PLAY Short Courses Deputy Head of Development (Alumni & Supporter Relations) Recently, I spent two days meeting with current students who Rachel Dyson 2016 had applied to be involved in our Easter telephone appeal. I Head of External Affairs Jo Hutchinson asked them all the same questions and their responses, regardless of subject or level of study, were astonishingly consistent and Head of Development Summer Arts Camp Duncan Barker often quite touching. New Summer Arts Camp for 11-14 years (in association with the Barbican) Marketing & Communications Officer When asked ‘Why did you choose to study at Guildhall?’, many Drama Summer School Rosanna Chianta students spoke of loving the ‘easy-going’, ‘friendly’, ‘progressive’ Acting in Shakespeare & Contemporary Theatre Writer & Editorial Consultant Acting in Musical Theatre environment at Guildhall; how they felt at home as soon as Nicola Sinclair Drama Summer School for 16-17 years they walked in for an open day, an audition or to visit a friend Art Direction & Design who was here before them. They talked of the collaborative Music Summer School Pentagram New Brass and Percussion Week Jessie Earle opportunities that arise from the combination of conservatoire Advanced Saxophone and drama school, and from the School’s partnerships with New Advanced Viola and Performance Health Contact external organisations such as the LSO, the Barbican and the New Advanced Oboe New Oboe and Cor Anglais Artistry Email Royal Opera House. -

Digital Concert Hall Where We Play Just for You

www.digital-concert-hall.com DIGITAL CONCERT HALL WHERE WE PLAY JUST FOR YOU PROGRAMME 2016/2017 Streaming Partner TRUE-TO-LIFE SOUND THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL AND INTERNET INITIATIVE JAPAN In the Digital Concert Hall, fast online access is com- Internet Initiative Japan Inc. is one of the world’s lea- bined with uncompromisingly high quality. Together ding service providers of high-resolution data stream- with its new streaming partner, Internet Initiative Japan ing. With its expertise and its excellent network Inc., these standards will also be maintained in the infrastructure, the company is an ideal partner to pro- future. The first joint project is a high-resolution audio vide online audiences with the best possible access platform which will allow music from the Berliner Phil- to the music of the Berliner Philharmoniker. harmoniker Recordings label to be played in studio quality in the Digital Concert Hall: as vivid and authen- www.digital-concert-hall.com tic as in real life. www.iij.ad.jp/en PROGRAMME 2016/2017 1 WELCOME TO THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL In the Digital Concert Hall, you always have Another highlight is a guest appearance the best seat in the house: seven days a by Kirill Petrenko, chief conductor designate week, twenty-four hours a day. Our archive of the Berliner Philharmoniker, with Mozart’s holds over 1,000 works from all musical eras “Haffner” Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s for you to watch – from five decades of con- “Pathétique”. Opera fans are also catered for certs, from the Karajan era to today. when Simon Rattle presents concert perfor- mances of Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre and The live broadcasts of the 2016/2017 Puccini’s Tosca. -

James Burton, Conductor

andris nelsons, ray and maria stata music director bernard haitink, lacroix family fund conductor emeritus seiji ozawa, music director laureate thomas adès, deborah and philip edmundson artistic partner Boston Symphony Orchestra 138th season, 2018–2019 Friday, January 11, 9:40pm A special post-concert “Casual Friday” performance by the tanglewood festival chorus james burton, conductor As part of tonight’s “Casual Friday” program, immediately following the BSO concert, the audience is invited to pick up refreshments at Symphony Hall’s first-floor lounge spaces and then return to the concert hall for a special performance by the BSO’s own Tanglewood Festival Chorus, led by its conductor James Burton, of Ildebrando Pizzetti’s “Messa di Requiem” for unaccompanied chorus. Alternatively, audience members may choose to attend the post-concert reception in Higginson Hall, tonight featuring live music with the Tucker Antell Quintet. pizzetti “messa di requiem,” for a cappella chorus I. Requiem (Introitus and Kyrie) II. Dies irae III. Sanctus IV. Agnus Dei V. Libera me Text and translation begin on page 2. Born in Parma, Italy, Ildebrando Pizzetti (1880-1968) at first showed a preference for the theater, only later, in 1895, entering Parma Conservatory to study music. With Italian opera at its height, Pizzetti began trying to combine his two interests, eventually collaborating with the famous writer Gabriele D’Annunzio on two operas and writing incidental music for his plays. Pizzetti was director of the Milan Conser- vatory, then taught at Rome’s Accademia di Santa Cecilia, retiring in 1958. He taught such important composers as Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Franco Donatoni, and Reginald Smith Brindle. -

Tanglewood Brochure

2020 SEASON AT-A-GLANCE In the 2020 Tanglewood season, BSO Music Director Andris Nelsons leads twelve BSO concerts including Act III of Wagner’s Tannhäuser (7/11) and three programs showcasing Paul Lewis in all five Beethoven piano concertos (7/17–19). Other highlights include: • a weekend-long celebration of the 100th anniversary of Isaac Stern’s birth, with performances by violinists Augustin Hadelich, Midori, Pamela Frank, and Joshua Bell (7/24–26) • the Tanglewood Festival Chorus’s 50th Anniversary celebrated with six BSO collaborations (7/10–11, 8/1–2, 8/22–23) • Keith Lockhart leads the Boston Pops in Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (8/21) and the annual John Williams’ Film Night, hosted by Mr. Williams (8/15) • Ozawa Hall appearances by the Mark Morris Dance Group (7/1 & 2), Meow Meow (7/8), Emerson String Quartet with Emanuel Ax (7/9), Paul Lewis (7/14), and more • Popular Artists concerts with Ringo Starr (6/19), Trey Anastasio (6/20), Judy Collins and Arlo Guthrie (6/21), and the return of Wait Wait, Don’t Tell Me! (8/27) The Tanglewood Music Center (TMC) is the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s summer academy for advanced musical study. The TMC offers an intensive schedule of study and performance for emerging professional instrumentalists, singers, conductors, and composers. Orchestra Concerts July 6, 13, 20, 28, August 10 & 16 Chamber Music Concerts Sundays, June 28–August 16 Vocal Concerts July 12, 16, 26, August 3 & 9 Prelude Concerts Saturdays, July 11–August 15 Festival of Contemporary Music August 6–10 TMC-BBC Radio 3 New Generation Artists Recital* Mondays, July 6–August 10 *Free recitals presented in association with BBC Radio 3 Special Events String Quartet MasterPass* June 21–28 Bach Cantatas June 28 Mark Morris Dance Group July 1 & 2 MasterPass* Wednesdays July 1, 8, 15, 22, August 8 & 12 Full Tilt* July 5 & 27 TLI-TMC OpenStudio* July 13, 14 & 24 *Presented in collaboration with TLI 2 2020 SEASON The Tanglewood Learning Institute (TLI) offers engaging programs for curious minds, year-round. -

Educators Summit PROGRAM

Educators Summit PROGRAM – Chicago – 2017 March 31 - April 1 | Embassy Suites by Hilton – Chicago Downtown 2 MEIEA Welcome to the 2017 Music anD Entertainment InDustry EDucators Association Summit! I’m excited to welcome you to Chicago, the home of Deep Dish Pizza, the Second City Comedy ensemble and great music, especially the Blues. This is my last MEIEA Summit as your President and I know we’ve planned a terrific three days of events, speakers and valuable content you can bring back to your respective campuses. Since we are in a city so well-known for Chicago Blues, I thought it was only fitting to bring the Blues to the Summit. I’m excited to interview a long-time friend and ally, Bruce Iglauer, Founder and President of Alligator Records (although I think his title might just be “Boss”). Bruce started Alligator more than 45 years ago and his passion for the Blues is still evidenced by his unwavering support for his recording artists and their work, and his commitment that artists AND labels are paid fairly by new technology services. We will also hear from Jeff McClusky, a veteran of our industry who has been an incredibly successful radio promotion executive, which is only one of his many talents and services he provides to our industry. In addition to our keynote speakers, we have a superstar legal update panel, several other topical panels and roundtables and many great paper presentations. Last year, MEIEA started a Thursday briefing session and we will continue that innovation with a late afternoon session from our friends and sponsors at SoundExchange. -

STAGE PRESENCE Costume and Make-Up in Indian Classical Dance

May 2021 ® ON Stagevolume 10 • issue 10 STAGE PRESENCE Costume and make-up in Indian classical dance A RICHER SOUND A FINE STATE New members join the SOI Glimpses of Maharashtra Chairman’s Note here is a general impression that with the lockdown, the NCPA is not functioning as before. While it is true that there is nothing Twhich can substitute a face-to-face encounter and/or meeting to achieve the desired result, the next best course is to gird up our loins and innovate ways in which the NCPA would most benefit and the employees, musicians, technicians, etc. would occupy themselves meaningfully. Having laid out these objectives before our heads of divisions, I must say that a modicum of success has been achieved. The musicians in residence of the SOI have been furiously preparing new programmes and have already, in the last month, recorded four of them fully for the digital platform. These have been recorded in the theatre and with better sound than when the audience is present. Similarly, full- year plans, conditions permitting, have been presented by the Indian Music, International Music, Dance and Theatre genres. Preparations are, therefore, underway to put together a year’s programme of likely performances when the lockdown and other bans are lifted and otherwise, recording online for the presence of the NCPA to be noted by its members and the public alike. Methods of management are being put together and we realise that getting the finest advisors in areas where we need these inputs is the cheapest way of keeping up with technology and modern practices. -

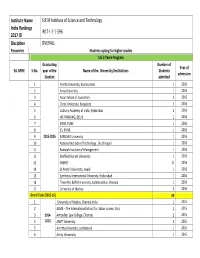

Higher Studies UG 3 Years Program Graduating Number of Year of 3A.GPHE S.No

Institute Name S.R.M Institute of Science and Technology India Rankings IR17‐I‐2‐1‐596 2017 ID Discipline OVERALL Parameter Students opting for higher studies UG 3 Years Program Graduating Number of Year of 3A.GPHE S.No. year of the Name of the University/Institutions Students admission Student admitted 1 Amrita University, Kochin,India 1 2016 2 Anna University 1 2016 3 Asian School of Journalism 2 2016 4 Christ University, Bangalore 2 2016 5 Culinary Academy of India, Hyderabad 3 2016 6 IAS TRAINING, DELHI 1 2016 7 IIIBM, PUNE 1 2016 8 IIS, PUNE. 1 2016 9 2015‐2016 KARUNYA University 1 2016 10 National Institute of Technology ,Tiruchirapalli 1 2016 11 Ramaiah Institute of Management 1 2016 12 Sheffield Hallam University 1 2016 13 SRMIST 17 2016 14 St.Peter’s University, Avadi 1 2016 15 Symbiosis International University, Hyderabad 1 2016 16 Times Pro &SRM University, Kattnkulathur, Chennai 1 2016 17 University of Madras 9 2016 Grand Total (2015‐16) 45 1 University of Madras, Chennai,India 1 2015 2 ALMA – The International School for Italian cuisine, Italy 1 2015 3 2014‐ Ambedkar Law College, Chennai 2 2015 4 2015 AMET University 2 2015 5 Amirtha University, coimbatore 1 2015 6 Amity Univerisity 1 2015 7 Anna University 1 2015 8 Christ University 4 2015 9 D G Vaishnav college 1 2015 10 DELHI Univerisity 3 2015 11 IMT, Dubai 1 2015 12 London University 1 2015 13 Loyola College, Chennai 2 2015 14 M.O.P. Vaishnav College for Women, Chennai 1 2015 15 SENECA COLLEGE, TORONTO, CANADA 1 2015 16 SRMIST 2 2015 17 Symbiosis International University