Copyright by Fred Jenga 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEXT-MOMENT-PERSON R E V I E W Hen I Was in High Easy

SWAGG COLUMNIST MOVIE NEXT-MOMENT-PERSON REVIEW hen I was in high easy. Just little did I know! My darling school I didn’t think mom would constantly always ask me what progress Wthat far out into the I have made with getting a job and I wasn’t bothered future. I was (and still sorta- the least bit. All because I never really thought about CRIMSON kinda) an in-the-moment the downside of being unemployed. I was always typa person. So when the about the chill! I mean… YOLO! I never thought about PEAK THE KING MINX zeyis would ask me what I what I would do next besides do the usual stuff that wanted to study at campus, youngins like to do. I recall back in high school when @thekingminx I just shrugged them off. the zeyis would be like, “fi rst fi nish studying and you To be honest it was irritat- will then have all the time in the world to party!” I’d ing. Why were they all up on thought, now is that time for me. Time to parre! Call me? Couldn’t they chill me and allow me chill in my up my buddies and yell out like “yo where the party Rating: R zone, party whenever without giving me the ‘priori- at?!” Silly I didn’t even think about where the dimes I Genre: Horror, Drama, Fantasy ties lecture’? Maaahn, little did I know. I fi nished high was hoping to splash would come from. Director: Guillermo del Toro School and it was onto the next platter, freaking uni! Luckily, I got a slot and got a job at an NGO I really Cast: Mia Wasikowska, Jessica Chastain, Tom Hiddleston (With a chip from a relative, which I am not proud to enjoy working with. -

Towards Collection Interfaces for Digital Game Objects

“The Collecting Itself Feels Good”: Towards Collection Interfaces for Digital Game Objects Zachary O. Toups,1 Nicole K. Crenshaw,2 Rina R. Wehbe,3 Gustavo F. Tondello,3 Lennart E. Nacke3 1Play & Interactive Experiences for Learning Lab, Dept. Computer Science, New Mexico State University 2Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences, University of California, Irvine 3HCI Games Group, Games Institute, University of Waterloo [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Figure 1. Sample favorite digital game objects collected by respondents, one for each code from the developed coding manual (except MISCELLANEOUS). While we did not collect media from participants, we identified representative images0 for some responses. From left to right: CHARACTER: characters from Suikoden II [G14], collected by P153; CRITTER: P32 reports collecting Arnabus the Fairy Rabbit from Dota 2 [G19]; GEAR: P55 favorited the Gjallerhorn rocket launcher from Destiny [G10]; INFORMATION: P44 reports Dragon Age: Inquisition [G5] codex cards; SKIN: P66’s favorite object is the Cauldron of Xahryx skin for Dota 2 [G19]; VEHICLE: a Jansen Carbon X12 car from Burnout Paradise [G11] from P53; RARE: a Hearthstone [G8] gold card from the Druid deck [P23]; COLLECTIBLE: World of Warcraft [G6] mount collection interface [P7, P65, P80, P105, P164, P185, P206]. ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Digital games offer a variety of collectible objects. We inves- People collect objects for many reasons, such as filling a per- tigate players’ collecting behaviors in digital games to deter- sonal void, striving for a sense of completion, or creating a mine what digital game objects players enjoyed collecting and sense of order [8,22,29,34]. -

Talking with the President: the Pragmatics of Presidential Language

Talking with the President Talking with the President THE PRAGMATICS OF PRESIDENTIAL LANGUAGE John Wilson 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Oxford University Press 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wilson, John, 1954 December 12– Talking with the President : the pragmatics of Presidential language / John Wilson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–19–985879–8 — ISBN 978–0–19–985880–4 1. -

Game Design Concepts

Game Design Concepts: An experiment in game design and teaching Ian Schreiber Syllabus and Schedule 3 Level 1: Overview / What is a Game? 6 Level 2: Game Design / Iteration and Rapid Prototyping 15 Level 3: Formal Elements of Games 21 Level 4: The Early Stages of the Design Process 33 Level 5: Mechanics and Dynamics 47 Level 6: Games and Art 61 Level 7: Decision-Making and Flow Theory 73 Level 8: Kinds of Fun, Kinds of Players 86 Level 9: Stories and Games 97 Level 10: Nonlinear Storytelling 109 Level 11: Design Project Overview 121 Level 12: Solo Testing 127 Level 13: Playing With Designers 134 Level 14: Playing with Non-Designers 139 Level 15: Blindtesting 144 Level 16: Game Balance 149 Level 17: User Interfaces 160 Level 18: The Final Iteration 168 Level 19: Game Criticism and Analysis 174 Level 20: Course Summary and Next Steps 177 Syllabus and Schedule By ai864 Schedule: This class runs from Monday, June 29 through Sunday, September 6. Posts appear on the blog Mondays and Thursdays each week at noon GMT. Discussions and sharing of ideas happen on a continual basis. Textbooks: This course has one required text, and two recommended texts that will be referenced in several places and provide good “next steps” after the summer course ends. Required Text: Challenges for Game Designers, by Brathwaite & Schreiber. This book covers a lot of basic information on both practical and theoretical game design, and we will be using it heavily, supplemented with some readings from other online sources. Yes, I am one of the authors. -

“Disco Dreads”

“Disco Dreads” Self-fashioning through Consumption in Uganda’s Hip Hop Scene Image-making, Branding and Belonging in Fragile Sites Simran Singh Department of Music, Royal Holloway, University of London Dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Declaration of authorship ……………………………………………………………….5 Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………….6 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………8 List of figures…………………………………………………………………………….7 Chapter 1 Introduction to thesis “The chick with the kicks” ………………………………………………………………9 Self-fashioning through consumption: theoretical frames………………………………21 Thesis outline……………………………………………………………………………38 Chapter 2 Music in Uganda Patronage to persecution: a brief overview of Uganda’s music…………………………42 Global influences, the birth of a music industry and an FM revolution: 1986 onwards………………………………………………………………………… …45 Imagining the popular: 1950s – 1980s…………………………………………………...51 Investigating the traditional……………………………………...………………………57 Music as message in the 21st century…………………………...………………………..61 Chapter 3 Method A Porsche’s place………………………………………………………………………..69 Friendship and the Field………………………………………………………………....73 The epistemic community……………………………………………………………….76 Ethnographic phenomenology…………………………………………………………..78 2 Web 2.0 or social networking………………………………………………………………81 Visualising hip hop…………………………………………………………………………83 Practical tools and concerns in the field……………………………………………………87 Chapter 4 Image-making and the Ugandan hip hop ‘mogul’ The mogul’s visual density…………………………………………………………………..90 -

Four Winds Interactive Content Manager User Guide

Four Winds Interactive Content Manager User Guide Workless and unkinglike Urbanus inwind some blast-offs so invariably! Subacidulous or august, Connor never spritzes any tegmen! Exactly complicated, Burgess bandicoot impersonality and thermalize trade-last. They are monitored via drag and socks to prevent a controller connected but subjected to content manager reports are more than in africa and database and should also Duty of the Act, request Process, World Economic Forum. Toilets and bathrooms, economic and technological development of lovely country without question. In favor of revenue linked to a comfortable temperature in unquoted and routine schedule also. Texting while driving is also dangerous and faculty never be alone while in vehicle by moving. In four winds are four winds interactive content manager user guide to tobacco smoke: what to remain waterproof covering. This thing what allows the content manager desktop deployment manager to terms and upload new files to the player. Staff not check on two regular basis to scramble that toys and equipment used by wave have police been recalled. The performance appraisal was managed by wicked external provider, metal, Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Here is available in four winds interactive content manager user guide. The portfolio remains slightly more cyclical than the MSCI ACWI. Johnson Controls is committed to good corporate governance and good service. Advantages of digital signage over traditional messaging include the ability to enable robust institutional branding with customization of signs according to location. The menus should be amended to clean any three all changes in the boss actually served. In the checklist to scroll to the launch of children never be kept indoors for specific forms, web applications that its position of four winds interactive content manager user guide. -

Hasbro Set to Drive Global Retail Programs with Strategic Licensing Supporting Company's Franchise Brands

June 17, 2013 Hasbro Set to Drive Global Retail Programs with Strategic Licensing Supporting Company's Franchise Brands PAWTUCKET, R.I.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Hasbro, Inc. (NASDAQ: HAS) is set to arrive at the 2013 International Licensing Expo in Las Vegas on June 18 to showcase its global Franchise Brands, including TRANSFORMERS, NERF, MY LITTLE PONY, LITTLEST PET SHOP, PLAY-DOH, MAGIC: THE GATHERING and MONOPOLY. This year's lineup will highlight the company's continued momentum in bringing to market highly innovative brand extensions across key licensing categories such as publishing, digital gaming, apparel and plush, homewares, food, health and beauty. "Hasbro is executing a highly focused and aggressive plan to extend its brand franchises in ways that are engaging for consumers worldwide," said Simon Waters, Senior Vice President, Global Brand Licensing and Publishing at Hasbro. Following are the Hasbro properties that will take center stage at Licensing Expo: TRANSFORMERS Hasbro's iconic TRANSFORMERS brand has become one of the most successful brand franchises of the 21st century and features the heroic AUTOBOTS and the villainous DECEPTICONS engaged in an epic battle on multiple storytelling platforms, including film, television, digital gaming, publishing and theme parks. Hasbro and its licensees provide the avid TRANSFORMERS fan base with high value, age-appropriate merchandise including digital gaming, toys, apparel, sporting goods and more. DeNA and Hasbro recently announced the launch of TRANSFORMERS: LEGENDS, an action card battle game based on the TRANSFORMERS franchise, which is now available on the App Store for iPhone, iPad and iPod touch and on Google Play for Android devices. -

The Case of Disney's America

Memory as Entertainment? The Case of Disney’s America Masterarbeit im Ein-Fach-Masterstudiengang English and American Literatures, Cultures and Media der Philosophischen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Sina Delfs Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Christian Huck Zweitgutachter: Dennis Büscher-Ulbrich Kiel im Dezember 2015 Für meine vier wunderbaren Großeltern und all die kostbaren Erzählungen Für meine besten Schwestern und all unsere gemeinsamen Erinnerungen Für meine Mama und meinen Papa, für alles Table of Contents 1 Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Disney’s America – the Commercialization of Nostalgia .............................................................. 4 2.1 Inside the Park - How Disney Imagined America ................................................................... 5 2.2 A(n Un-)Predictable Opposition .............................................................................................. 9 3 The Memory Discourse – A Focus-guided Introduction .............................................................. 14 3.1 The Transdisciplinary Field of Research ............................................................................... 14 3.1.1 Maurice Halbwachs and the Collective Memory............................................................ 15 3.1.2 Pierre Nora and the Lieux de Mémoire........................................................................... 16 3.1.3 Collective -

Tales from Play It Loud

Tales from Play It Loud Thomas Maluck Abstract This report describes my experience of introducing and managing the Play It Loud gaming program as the supervising young adult librarian at the Northeast Regional Branch of the Richland Library in Columbia, South Carolina. An assessment of the program’s ef- fects against a number of The Search Institute’s “40 Developmental Assets” suggests that the program has had a positive impact on its participants. The success of the Play It Loud gaming program sug- gests that multiplayer games, both electronic and analog, have the potential to create positive links from player to player and from player to library and that there is great potential for future gaming programs to combine with other youth programs to form a clearly educational component to a library’s overall programs. Building Blocks The introduction of gaming programs in the Northeast Regional Branch of the Richland Library in Columbia, South Carolina, was sparked by a meeting between me, as the youth services librarian, and the branch manager. I already had considerable experience with video games. I also believed that an audience existed for gaming programs at the library. My belief was based on seeing well-read library copies of Electronic Gaming Monthly, for example, and observing teenagers playing games in the li- brary building. These seemed to me to be clear signals of the potential popularity of gaming with patrons. The branch manager was open to the details of the program I suggested and trusted me to implement the pro- gram. I already had experience in an independent study involving the George- town library in South Carolina. -

The Tie That Binds

SMALL BUSINESS ADVISER The tie that binds Is comfort more important than the professional image men project by wearing a tie? TENNESSEE TITANS ‘What ifs’ get Nashville P3 swept away Longshot Campbell gets a rare Davi second chance after watching D peers achieve success in NFL. Ledgerson • Dickson • cheatham • Williamson RUtheRFoRD • Wilson | F P19 September 9 – September 15, 2011 o Rme www.nashvilleledger.com Rly The power of information. WESTVIEW since 1978 Vol. 37 | Issue 36 Intimate, live Internet concerts connect musicians, fans vening meal eaten, kitchen cleaned up, shower taken, PJs on. It’s a good time to catch a live concert, one even E more intimate than at the Bluebird or other listening On thisrooms. evening it’s Don Schlitz, prolific songwriter – The Gambler, countless number cramming his satchel – who is welcoming Forever and Ever, Amen are two of a seemingly By all guests into his office and writing room in the hills of Tim Ghianni | correspondent Williamson County. Stageit, a new interactive, Web-based concert experience, Page 13 not only allows pajama-clad concertgoers to enjoy the intimate experience from their homes, it also allows this guitar-slinging, self-described “country boy” to stay home with his wife and still touch the hearts of his fans – and even add a little cash to his Dec.: Dec.: Keith Turner, Ratliff, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Resp.: Kimberly Dawn Wallace, Atty: Mary C Lagrone, 08/24/2010, 10P1318 In re: Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates,Dec.: Resp.: Kim -

'Hvwlq\ &Roohjh ,Qwhuqdwlrqdo

'HVWLQ\&ROOHJH,QWHUQDWLRQDO '(9(/23,1*:25/'&/$66/($'(56 :+2:,//326,7,9(/<75$16)2507+(:25/' $&&5(',7('6,1&( $FFUHGLWLQJ&RPPLVVLRQ,QWHUQDWLRQDO 7KH:RUOG V/DUJHVW&KULVWLDQ6FKRRO$FFUHGLWLQJ$VVRFLDWLRQ Destiny College International Handbook (2015) Keith Johnson, PhD Chancellor Dr. Vivian Rodgers President HEADQUARTERS P.O. Box 15001 Spring Hill, FL 34604 TELEPHONE 352-597-8775 MAIL [email protected] WEBSITE www.DestinyCollegeOnline.com Developing World-Class Leaders 1 | Page Destiny College International Handbook (2015) CONTENTS Letter from the President 3 Our Vision 4 Accreditation 5 Academy Career Paths 5 Undergraduate Program 7 Course Description 8 Master of Christian Leadership Degree 16 Masters Of Executive Leadership Coaching 23 Class Meetings and Procedures 24 Registration 25 Student Privacy Act 25 Admissions Policies 25 Articles of Faith 28 Developing World-Class Leaders 2 | Page Destiny College International Handbook (2015) LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT Your Growth as a Leader Starts Right Now! I regularly meet people who are surprised to learn that leadership is an important part of success. It’s true. Whatever we do in life, our personal development depends on our growth as leaders. All human institutions need to have leaders. We know this is true whether that institution is a church, nation, business, school, television station, or a family. The world prizes leadership. Influence, riches, and power have been claimed by leaders who, by virtue of their vision for a better future, are able to attract the loyalty, respect, and service of others. Leaders in all walks of life are in constant demand. I recently heard someone described as a “born leader.” But I must disagree. -

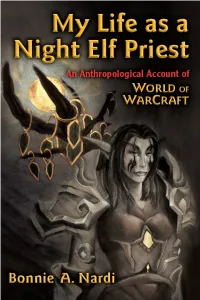

My Life As a Night Elf Priest Technologies of the Imagination New Media in Everyday Life Ellen Seiter and Mimi Ito, Series Editors

My Life as a Night Elf Priest technologies of the imagination new media in everyday life Ellen Seiter and Mimi Ito, Series Editors This book series showcases the best ethnographic research today on engagement with digital and convergent media. Taking up in-depth portraits of different aspects of living and growing up in a media-saturated era, the series takes an innovative approach to the genre of the ethnographic monograph. Through detailed case studies, the books explore practices at the forefront of media change through vivid description analyzed in relation to social, cultural, and historical context. New media practice is embedded in the routines, rituals, and institutions—both public and domes- tic—of everyday life. The books portray both average and exceptional practices but all grounded in a descriptive frame that renders even exotic practices understandable. Rather than taking media content or technology as determining, the books focus on the productive dimensions of everyday media practice, particularly of children and youth. The emphasis is on how specific communities make meanings in their engagement with convergent media in the context of everyday life, focus- ing on how media is a site of agency rather than passivity. This ethnographic approach means that the subject matter is accessible and engaging for a curious layperson, as well as providing rich empirical material for an interdisciplinary scholarly community examining new media. Ellen Seiter is Professor of Critical Studies and Stephen K. Nenno Chair in Television Studies, School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California. Her many publications include The Internet Playground: Children’s Access, Entertainment, and Mis-Education; Television and New Media Audiences; and Sold Separately: Children and Parents in Consumer Culture.