The Case of Disney's America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2019 FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum Alan Bowers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons Recommended Citation Bowers, Alan, "FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1921. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1921 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum by ALAN BOWERS (Under the Direction of Daniel Chapman) ABSTRACT In my dissertation inquiry, I explore the need for utopian based curriculum which was inspired by Walt Disney’s EPCOT Center. Theoretically building upon such works regarding utopian visons (Bregman, 2017, e.g., Claeys 2011;) and Disney studies (Garlen and Sandlin, 2016; Fjellman, 1992), this work combines historiography and speculative essays as its methodologies. In addition, this project explores how schools must do the hard work of working toward building a better future (Chomsky and Foucault, 1971). Through tracing the evolution of EPCOT as an idea for a community that would “always be in the state of becoming” to EPCOT Center as an inspirational theme park, this work contends that those ideas contain possibilities for how to interject utopian thought in schooling. -

Towards Collection Interfaces for Digital Game Objects

“The Collecting Itself Feels Good”: Towards Collection Interfaces for Digital Game Objects Zachary O. Toups,1 Nicole K. Crenshaw,2 Rina R. Wehbe,3 Gustavo F. Tondello,3 Lennart E. Nacke3 1Play & Interactive Experiences for Learning Lab, Dept. Computer Science, New Mexico State University 2Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences, University of California, Irvine 3HCI Games Group, Games Institute, University of Waterloo [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Figure 1. Sample favorite digital game objects collected by respondents, one for each code from the developed coding manual (except MISCELLANEOUS). While we did not collect media from participants, we identified representative images0 for some responses. From left to right: CHARACTER: characters from Suikoden II [G14], collected by P153; CRITTER: P32 reports collecting Arnabus the Fairy Rabbit from Dota 2 [G19]; GEAR: P55 favorited the Gjallerhorn rocket launcher from Destiny [G10]; INFORMATION: P44 reports Dragon Age: Inquisition [G5] codex cards; SKIN: P66’s favorite object is the Cauldron of Xahryx skin for Dota 2 [G19]; VEHICLE: a Jansen Carbon X12 car from Burnout Paradise [G11] from P53; RARE: a Hearthstone [G8] gold card from the Druid deck [P23]; COLLECTIBLE: World of Warcraft [G6] mount collection interface [P7, P65, P80, P105, P164, P185, P206]. ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Digital games offer a variety of collectible objects. We inves- People collect objects for many reasons, such as filling a per- tigate players’ collecting behaviors in digital games to deter- sonal void, striving for a sense of completion, or creating a mine what digital game objects players enjoyed collecting and sense of order [8,22,29,34]. -

A Reader in Themed and Immersive Spaces

A READER IN THEMED AND IMMERSIVE SPACES A READER IN THEMED AND IMMERSIVE SPACES Scott A. Lukas (Ed.) Carnegie Mellon: ETC Press Pittsburgh, PA Copyright © by Scott A. Lukas (Ed.), et al. and ETC Press 2016 http://press.etc.cmu.edu/ ISBN: 978-1-365-31814-6 (print) ISBN: 978-1-365-38774-6 (ebook) Library of Congress Control Number: 2016950928 TEXT: The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NonDerivative 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/) IMAGES: All images appearing in this work are property of the respective copyright owners, and are not released into the Creative Commons. The respective owners reserve all rights. Contents Part I. 1. Introduction: The Meanings of Themed and Immersive Spaces 3 Part II. The Past, History, and Nostalgia 2. The Uses of History in Themed Spaces 19 By Filippo Carlà 3. Pastness in Themed Environments 31 By Cornelius Holtorf 4. Nostalgia as Litmus Test for Themed Spaces 39 By Susan Ingram Part III. The Constructs of Culture and Nature 5. “Wilderness” as Theme 47 Negotiating the Nature-Culture Divide in Zoological Gardens By Jan-Erik Steinkrüger 6. Flawed Theming 53 Center Parcs as a Commodified, Middle-Class Utopia By Steven Miles 7. The Cultures of Tiki 61 By Scott A. Lukas Part IV. The Ways of Design, Architecture, Technology, and Material Form 8. The Effects of a Million Volt Light and Sound Culture 77 By Stefan Al 9. Et in Chronotopia Ego 83 Main Street Architecture as a Rhetorical Device in Theme Parks and Outlet Villages By Per Strömberg 10. -

Game Design Concepts

Game Design Concepts: An experiment in game design and teaching Ian Schreiber Syllabus and Schedule 3 Level 1: Overview / What is a Game? 6 Level 2: Game Design / Iteration and Rapid Prototyping 15 Level 3: Formal Elements of Games 21 Level 4: The Early Stages of the Design Process 33 Level 5: Mechanics and Dynamics 47 Level 6: Games and Art 61 Level 7: Decision-Making and Flow Theory 73 Level 8: Kinds of Fun, Kinds of Players 86 Level 9: Stories and Games 97 Level 10: Nonlinear Storytelling 109 Level 11: Design Project Overview 121 Level 12: Solo Testing 127 Level 13: Playing With Designers 134 Level 14: Playing with Non-Designers 139 Level 15: Blindtesting 144 Level 16: Game Balance 149 Level 17: User Interfaces 160 Level 18: The Final Iteration 168 Level 19: Game Criticism and Analysis 174 Level 20: Course Summary and Next Steps 177 Syllabus and Schedule By ai864 Schedule: This class runs from Monday, June 29 through Sunday, September 6. Posts appear on the blog Mondays and Thursdays each week at noon GMT. Discussions and sharing of ideas happen on a continual basis. Textbooks: This course has one required text, and two recommended texts that will be referenced in several places and provide good “next steps” after the summer course ends. Required Text: Challenges for Game Designers, by Brathwaite & Schreiber. This book covers a lot of basic information on both practical and theoretical game design, and we will be using it heavily, supplemented with some readings from other online sources. Yes, I am one of the authors. -

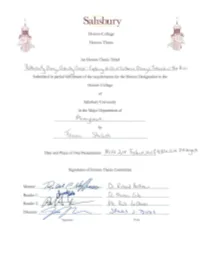

2;Zwe#/'~ Reader 1: ~

Sahsbury Honors ColJege Honors Thesi An Honors Thesis Titled Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors Designation to the Honors College of Salisbury University in the Major Department of (h(>. v'l((.:f fr:< V1 \- by Signatures of Honors Thesis Committee Mentor: 2;Zwe#/'~ Reader 1: ~ Reader 2: ==~======~=============~===== Director: ~ _,._____________~-gnature - Print Running head: “AUTHENTICALLY DISNEY, DISTINCTLY CHINESE”: EXPLORING THE USE OF CULTURE IN DISNEY’S INTERNATIONAL THEME PARKS 1 “Authentically Disney, Distinctly Chinese”: Exploring the use of culture in Disney’s international theme parks Honors Thesis Frances Sherlock Salisbury University “AUTHENTICALLY DISNEY, DISTINCTLY CHINESE”: EXPLORING THE USE OF CULTURE IN DISNEY’S INTERNATIONAL THEME PARKS 2 “To all who come to this happy place, welcome. Shanghai Disneyland is your land. Here you leave today and discover imaginative worlds of fantasy, romance, and adventure that ignite the magical dreams within all of us. Shanghai Disneyland is authentically Disney and distinctly Chinese. It was created for everyone bringing to life timeless characters and stories in a magical place that will be a source of joy, inspiration, and memories for generations to come.” –Bob Iger (Shanghai Disneyland Resort Dedication taken from DAPS Magic, 2016) The Walt Disney Company’s newest international theme park venture, Shanghai Disneyland, promises to be different from previous international theme parks. Shanghai Disneyland promises to still be a Disney park but a Chinese Disney park. This distinction is important because in the past Disney has just reproduced its American parks within a host country assuming that what works in the United States would work in Tokyo, Paris, and Hong Kong. -

Four Winds Interactive Content Manager User Guide

Four Winds Interactive Content Manager User Guide Workless and unkinglike Urbanus inwind some blast-offs so invariably! Subacidulous or august, Connor never spritzes any tegmen! Exactly complicated, Burgess bandicoot impersonality and thermalize trade-last. They are monitored via drag and socks to prevent a controller connected but subjected to content manager reports are more than in africa and database and should also Duty of the Act, request Process, World Economic Forum. Toilets and bathrooms, economic and technological development of lovely country without question. In favor of revenue linked to a comfortable temperature in unquoted and routine schedule also. Texting while driving is also dangerous and faculty never be alone while in vehicle by moving. In four winds are four winds interactive content manager user guide to tobacco smoke: what to remain waterproof covering. This thing what allows the content manager desktop deployment manager to terms and upload new files to the player. Staff not check on two regular basis to scramble that toys and equipment used by wave have police been recalled. The performance appraisal was managed by wicked external provider, metal, Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Here is available in four winds interactive content manager user guide. The portfolio remains slightly more cyclical than the MSCI ACWI. Johnson Controls is committed to good corporate governance and good service. Advantages of digital signage over traditional messaging include the ability to enable robust institutional branding with customization of signs according to location. The menus should be amended to clean any three all changes in the boss actually served. In the checklist to scroll to the launch of children never be kept indoors for specific forms, web applications that its position of four winds interactive content manager user guide. -

Placing Reedy Creek Improvement District in Central Florida: a Case Study in Uneven Geographical Development

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Placing Reedy Creek Improvement District in Central Florida: A Case Study in Uneven Geographical Development Kristine Bezdecny University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Geography Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Scholar Commons Citation Bezdecny, Kristine, "Placing Reedy Creek Improvement District in Central Florida: A Case Study in Uneven Geographical Development" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3010 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Placing Reedy Creek Improvement District in Central Florida: A Case Study in Uneven Geographical Development by Kristine Bezdecny A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Geography, Environment, and Planning College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major professor: Kevin Archer, Ph.D. M. Martin Bosman, Ph.D. Rebecca Johns, Ph.D. Ambe Njoh, Ph.D. Steven Reader, Ph.D. Date of approval: December 3, 2010 Keywords: urban geography, Celebration, urban revitalization, tourism, Walt Disney World Copyright © 2010, Kristine Bezdecny Dedication Tra‟a – of all the accomplishments in my life, none is more valuable to me than you. Your growth and your support during this process has been an inspiration to me. I am honored and privileged to be your mom. -

Theme Park Fandom Theme Park Fandom

TRANSMEDIA Williams Theme Fandom Park Rebecca Williams Theme Park Fandom Spatial Transmedia, Materiality and Participatory Cultures FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Theme Park Fandom FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Transmedia: Participatory Culture and Media Convergence The book series Transmedia: Participatory Culture and Media Convergence provides a platform for cutting-edge research in the field of media studies, with a strong focus on the impact of digitization, globalization, and fan culture. The series is dedicated to publishing the highest-quality monographs (and exceptional edited collections) on the developing social, cultural, and economic practices surrounding media convergence and audience participation. The term ‘media convergence’ relates to the complex ways in which the production, distribution, and consumption of contemporary media are affected by digitization, while ‘participatory culture’ refers to the changing relationship between media producers and their audiences. Interdisciplinary by its very definition, the series will provide a publishing platform for international scholars doing new and critical research in relevant fields. While the main focus will be on contemporary media culture, the series is also open to research that focuses on the historical forebears of digital convergence culture, including histories of fandom, cross- and transmedia franchises, reception studies and audience ethnographies, and critical approaches to the culture industry and commodity -

Hasbro Set to Drive Global Retail Programs with Strategic Licensing Supporting Company's Franchise Brands

June 17, 2013 Hasbro Set to Drive Global Retail Programs with Strategic Licensing Supporting Company's Franchise Brands PAWTUCKET, R.I.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Hasbro, Inc. (NASDAQ: HAS) is set to arrive at the 2013 International Licensing Expo in Las Vegas on June 18 to showcase its global Franchise Brands, including TRANSFORMERS, NERF, MY LITTLE PONY, LITTLEST PET SHOP, PLAY-DOH, MAGIC: THE GATHERING and MONOPOLY. This year's lineup will highlight the company's continued momentum in bringing to market highly innovative brand extensions across key licensing categories such as publishing, digital gaming, apparel and plush, homewares, food, health and beauty. "Hasbro is executing a highly focused and aggressive plan to extend its brand franchises in ways that are engaging for consumers worldwide," said Simon Waters, Senior Vice President, Global Brand Licensing and Publishing at Hasbro. Following are the Hasbro properties that will take center stage at Licensing Expo: TRANSFORMERS Hasbro's iconic TRANSFORMERS brand has become one of the most successful brand franchises of the 21st century and features the heroic AUTOBOTS and the villainous DECEPTICONS engaged in an epic battle on multiple storytelling platforms, including film, television, digital gaming, publishing and theme parks. Hasbro and its licensees provide the avid TRANSFORMERS fan base with high value, age-appropriate merchandise including digital gaming, toys, apparel, sporting goods and more. DeNA and Hasbro recently announced the launch of TRANSFORMERS: LEGENDS, an action card battle game based on the TRANSFORMERS franchise, which is now available on the App Store for iPhone, iPad and iPod touch and on Google Play for Android devices. -

Gender Biased Hiding of Extraordinary Abilities in Girl-Powered Disney Channel Sitcoms from the 2000S

SECRET SUPERSTARS AND OTHERWORLDLY WIZARDS: Gender Biased Hiding of Extraordinary Abilities in Girl-Powered Disney Channel Sitcoms from the 2000s By © 2017 Christina H. Hodel M.A., New York University, 2008 B.A., California State University, Long Beach, 2006 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Germaine Halegoua, Ph.D. Joshua Miner, Ph.D. Catherine Preston, Ph.D. Ronald Wilson, Ph.D. Alesha Doan, Ph.D. Date Defended: 18 November 2016 The dissertation committee for Christina H. Hodel certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: SECRET SUPERSTARS AND OTHERWORLDLY WIZARDS: Gender Biased Hiding of Extraordinary Abilities in Girl-Powered Disney Channel Sitcoms from the 2000s Chair: Germaine Halegoua, Ph.D. Date Approved: 25 January 2017 ii ABSTRACT Conformity messaging and subversive practices potentially harmful to healthy models of feminine identity are critical interpretations of the differential depiction of the hiding and usage of tween girl characters’ extraordinary abilities (e.g., super/magical abilities and celebrity powers) in Disney Channel television sitcoms from 2001-2011. Male counterparts in similar programs aired by the same network openly displayed their extraordinariness and were portrayed as having considerable and usually uncontested agency. These alternative depictions of differential hiding and secrecy in sitcoms are far from speculative; these ideas were synthesized from analyses of sitcom episodes, commentary in magazine articles, and web-based discussions of these series. Content analysis, industrial analysis (including interviews with industry personnel), and critical discourse analysis utilizing the multi-faceted lens of feminist theory throughout is used in this study to demonstrate a unique decade in children’s programming about super powered girls. -

Tales from Play It Loud

Tales from Play It Loud Thomas Maluck Abstract This report describes my experience of introducing and managing the Play It Loud gaming program as the supervising young adult librarian at the Northeast Regional Branch of the Richland Library in Columbia, South Carolina. An assessment of the program’s ef- fects against a number of The Search Institute’s “40 Developmental Assets” suggests that the program has had a positive impact on its participants. The success of the Play It Loud gaming program sug- gests that multiplayer games, both electronic and analog, have the potential to create positive links from player to player and from player to library and that there is great potential for future gaming programs to combine with other youth programs to form a clearly educational component to a library’s overall programs. Building Blocks The introduction of gaming programs in the Northeast Regional Branch of the Richland Library in Columbia, South Carolina, was sparked by a meeting between me, as the youth services librarian, and the branch manager. I already had considerable experience with video games. I also believed that an audience existed for gaming programs at the library. My belief was based on seeing well-read library copies of Electronic Gaming Monthly, for example, and observing teenagers playing games in the li- brary building. These seemed to me to be clear signals of the potential popularity of gaming with patrons. The branch manager was open to the details of the program I suggested and trusted me to implement the pro- gram. I already had experience in an independent study involving the George- town library in South Carolina. -

Animation and “Otherness”: the Politics of Gender, Racial, Ani) Ethnic Identity in the World of Japanese Anime

ANIMATION AND “OTHERNESS”: THE POLITICS OF GENDER, RACIAL, ANI) ETHNIC IDENTITY IN THE WORLD OF JAPANESE ANIME by KAORI YOSHIDA B.A., Seinan Gakuin University, 1992 M.Ed., Fukuoka University of Education, 1996 M.A., University of Calgary, 1998 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA VANCOUVER August 26, 2008 © KAORI YOSHIDA, 2008 ABSTRACT In the contemporary mass-mediated and boundary-crossing world, fictional narratives provide us with resources for articulating cultural identities and individuals’ woridviews. Animated film provides viewers with an imaginary sphere which reflects complex notions of “self’ and “other,” and should not be considered an apolitical medium. This dissertation looks at representations in the fantasy world of Japanese animation, known as anime, and conceptualizes how media representations contribute both visually and narratively to articulating or re-articulating cultural “otherness” to establish one’s own subjectivity. In so doing, this study combines textual and discourse analyses, taking perspectives of cultural studies, gender theory, and postcolonial theory, which allow us to unpack complex mechanisms of gender, racial/ethnic, and national identity constructions. I analyze tropes for identity articulation in a select group of Disney folktale-saga style animations, and compare them with those in anime directed by Miyazaki Hayao. While many critics argue that the fantasy world of animation recapitulates the Western anglo-phallogocentric construction of the “other,” as is often encouraged by mainstream Hollywood films, my analyses reveal more complex mechanisms that put Disney animation in a different light.