Placing Reedy Creek Improvement District in Central Florida: a Case Study in Uneven Geographical Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Overview

DISNEY CRUISE LINE Environmental Overview Media Contact: At Disney Cruise Line, we are dedicated to Disney Cruise Line minimizing our impact on the environment 407.566.3648 through efforts focused on utilizing new http://www.dclnews.com technologies, increasing fuel efficiency, minimizing waste and promoting conservation worldwide. We strive to instill positive environmental stewardship in our cast and crew members and seek to inspire others through programs that engage our guests and the communities in our ports of call. Environmental Officers All Disney Cruise Line ships have dedicated Environmental Officers who are ranked among the most senior leaders on board. t Highly Specialized Expertise: Our Environmental Officers possess previous maritime experience and specialized training in environmental regulations and systems. Environmental Officers aboard t Responsibilities: These leaders monitor the ship’s overall water quality Disney ships are responsible and supply, train all officers and crew members on waste minimization and for monitoring water quality, in environmental safety programs and oversee multiple environmental initiatives, addition to other duties. including all shipboard recycling efforts. Waste Minimization Great care is taken onboard all Disney ships to reduce waste and conserve resources whenever possible. t Recycling: Shipboard recycling processes help to eliminate more than 600 tons of metals, glass, plastic and paper from traditional waste streams each year. Each Disney Cruise Line crew members stateroom on all four Disney Cruise Line ships contains a recycling bin for plastic, are careful to sort recyclables into paper and aluminum. waste receptacles. t Condensation: Naturally occurring condensation from the ships’ onboard air- conditioning units is recycled to supply fresh water for onboard laundry facilities and for cleaning the outer decks of the ships, saving more than 30 million gallons of fresh water each year. -

A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2019 FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum Alan Bowers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons Recommended Citation Bowers, Alan, "FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1921. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1921 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum by ALAN BOWERS (Under the Direction of Daniel Chapman) ABSTRACT In my dissertation inquiry, I explore the need for utopian based curriculum which was inspired by Walt Disney’s EPCOT Center. Theoretically building upon such works regarding utopian visons (Bregman, 2017, e.g., Claeys 2011;) and Disney studies (Garlen and Sandlin, 2016; Fjellman, 1992), this work combines historiography and speculative essays as its methodologies. In addition, this project explores how schools must do the hard work of working toward building a better future (Chomsky and Foucault, 1971). Through tracing the evolution of EPCOT as an idea for a community that would “always be in the state of becoming” to EPCOT Center as an inspirational theme park, this work contends that those ideas contain possibilities for how to interject utopian thought in schooling. -

Disney Dream & Disney Fantasy Deck

DISNEY DREAM & DISNEY FANTASY DECK PLANS STATEROOM AMENITIES Staterooms have tub/shower, flat-screen TV, ample closet space, in-room safe, hair CONCIERGE ROYAL SUITE CONCIERGE 1-BEDROOM SUITE CONCIERGE FAMILY OCEANVIEW DELUXE FAMILY OCEANVIEW DELUXE OCEANVIEW DELUXE FAMILY OCEANVIEW DELUXE OCEANVIEW DELUXE INSIDE STATEROOM STANDARD INSIDE dryer, phone with voicemail messaging and WITH VERANDAH (Category R) WITH VERANDAH (Category T) STATEROOM WITH VERANDAH STATEROOM WITH VERANDAH STATEROOM WITH VERANDAH STATEROOM (Category 8) STATEROOM (Category 9) (Category 10) STATEROOM (Category 11) individual climate control. One master bedroom with queen- One bedroom with queen-size bed, (Category V) (Category 4) (Categories 5, 6 and 7) Queen-size bed, single Queen-size bed, single Queen-size bed, single Queen-size bed, single size bed, one wall pull-down double living area with double convertible Queen-size bed, double convertible Queen-size bed, single convertible Queen-size bed, single convertible sofa, wall pull-down convertible sofa, upper berth convertible sofa, upper berth convertible sofa, upper berth Exact amenities described may vary slightly bed, and one wall pull-down single sofa, one wall single pull-down bed in sofa, upper berth pull-down bed, sofa, wall pull-down bed (in most) and convertible sofa, upper berth bed (in most) or upper berth pull-down bed (in some), split pull-down bed (in some), split pull-down bed (in some), bath depending on stateroom location. Stateroom bed in living room, two bathrooms, living room, walk-in closets, whirlpool full bath with round tub and shower, upper berth pull-down bed (in some), pull-down bed (if sleeping four), pull-down bed (in some), split bath with tub and shower. -

Disney Cruise Line Brochure

Disney Cruise Vacations Wonders All Around WELCOME ABOARD DISNEY CRUISE LINE The enchantment begins the moment you arrive. You're swept up into a fantastical world of Disney Service, world-class entertainment and unforgettable dining. Here, adults find excitement and indulgence. Kids, tweens and teens discover amazing clubs and endless adventures. And together, you create memories that will last a lifetime. © Copyright Disney. All rights reserved. Itineraries and sail dates are subject to change. Port order may vary. Wonders All Around IT'S ALL HERE. AND IT'S ALL INCLUDED. ENCHANTING EXTRAS FOR EVERY MEMBER OF YOUR CREW On Disney Cruises, it's all those little extras that add up to the most magical vacation of your life--- and it's all included. Enjoy everything from Broadway-style musicals, first-run films, special moments with Disney Characters and themed deck parties for the whole family--most voyages even include fireworks. If you're looking for a luxurious space tailored to your family's style and preferences, discover some of the most spacious staterooms at sea aboard Disney Cruise Line. Most Caribbean and Bahamian sailings stop at our private island paradise Disney Castaway Cay. With unique areas for every member of the family, everyone will find the relaxation they're looking for. On board, you'll discover amazing kids' clubs where kids can play from sunup until long after sundown with care provided by specially trained Disney counselors. And there are immersive spaces and activities for tweens and teens. Throughout your cruise, you'll experience a variety of restaurants for every taste. -

Holiday Planning Guide

Holiday Planning Guide For more information, visit DisneyParks.com.au Visit your travel agent to book your magical Disney holiday. The information in this brochure is for general reference only. The information is correct as of June 2018, but is subject to change without prior notice. ©Disney © & TM Lucasfilm Ltd. ©Disney•Pixar ©Disney. 2 | Visit DisneyParks.com.au to learn more, or contact your travel agent to book. heme T Park: Shanghai Disneyland Disney Resort Hotels: Park Toy Story Hotel andShanghai Disneyland Hotel ocation: L Pudong District, Shanghai Theme Parks: Disneyland Park and hemeT Parks: DisneyCaliforniaAdventurePark Epcot Magic ,Disney’s Disney Resort Hotels: Disneyland Hotel, Kingdom and Disney’s Hollywood Pa Pg 20 Disney’sGrandCalifornianHotel & Spa rk, Water Parks: Animal Studios and Disney’sParadisePier Hotel Kingdom Water Park, Disney’s Location: Anaheim, California USA B Water Park Disney’s lizzard T Beach isneyD Resort Hotels: yphoon Lagoon Pg 2 ocation:L Orlando, Florida25+ USA On-site Hotels Pg 6 Theme Parks: Disneyland® Park and WaltDisneyStudios® Park amilyF Resort unty’sA Beach House Kids Club Disney Resort Hotels: 6 onsite hotels aikoloheW Valley Water playground and a camp site hemeT Park: Location: Marne-la-Vallée, Paris, France aniwai,L A Disney Spa and Disney Resort Hotels:Hong Kong Painted Sky Teen Spa Disney Explorers Lodge andDisneyland Disney’s Disneyland ocation: L Ko Olina, Hawai‘i Pg 18 Hollywood Hotel Park isneyD Magic, ocation:L Hotel, Disney Disney Wonder, Dream Lantau Island, Hong Kong and Pg 12 Character experiences,Disney Live Shows, Fantasy Entertainment and Dining ©Disney ocation: L Select sailing around Alaska and Europe. -

A Reader in Themed and Immersive Spaces

A READER IN THEMED AND IMMERSIVE SPACES A READER IN THEMED AND IMMERSIVE SPACES Scott A. Lukas (Ed.) Carnegie Mellon: ETC Press Pittsburgh, PA Copyright © by Scott A. Lukas (Ed.), et al. and ETC Press 2016 http://press.etc.cmu.edu/ ISBN: 978-1-365-31814-6 (print) ISBN: 978-1-365-38774-6 (ebook) Library of Congress Control Number: 2016950928 TEXT: The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NonDerivative 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/) IMAGES: All images appearing in this work are property of the respective copyright owners, and are not released into the Creative Commons. The respective owners reserve all rights. Contents Part I. 1. Introduction: The Meanings of Themed and Immersive Spaces 3 Part II. The Past, History, and Nostalgia 2. The Uses of History in Themed Spaces 19 By Filippo Carlà 3. Pastness in Themed Environments 31 By Cornelius Holtorf 4. Nostalgia as Litmus Test for Themed Spaces 39 By Susan Ingram Part III. The Constructs of Culture and Nature 5. “Wilderness” as Theme 47 Negotiating the Nature-Culture Divide in Zoological Gardens By Jan-Erik Steinkrüger 6. Flawed Theming 53 Center Parcs as a Commodified, Middle-Class Utopia By Steven Miles 7. The Cultures of Tiki 61 By Scott A. Lukas Part IV. The Ways of Design, Architecture, Technology, and Material Form 8. The Effects of a Million Volt Light and Sound Culture 77 By Stefan Al 9. Et in Chronotopia Ego 83 Main Street Architecture as a Rhetorical Device in Theme Parks and Outlet Villages By Per Strömberg 10. -

Spring2014 • Volume23 • Number1 Welcome Home

spring2014 • Volume23 • Number1 welcOme home. Shrouded in darkness, concealed with caution tape and faintly smelling of commercial-grade latex, my workspace on a recent morning had all the makings of a crime scene investigation, minus the actual crime. (Seems the ridicule of an innocent man on the occasion of his 40th birthday is still legal in this country.) Picture the children’s-play-area ball pit at your local pizza joint or fast-food establishment, only with more insults and (slightly) less bacteria. “Friends” had engulfed my desk in a sea of black balloons, each emblazoned with a different dig from a clever co-worker. Excavating the area like a young Indiana Jones, I read everything from “our interns were born when you were in high school” to “you know you’re 40 when someone offers you a seat on the monorail…and you don’t refuse.” While I may have been surprised (and, truth be told, delighted) by the extremity of the effort, I wasn’t surprised by the effort itself. Having now been part of the Disney Vacation Club Cast family for the better part of a decade, I know how much this team loves to celebrate. From births to birthdays, awards to anniversaries, changes in our community to changes in humidity, rare is the month that doesn’t bring cause for celebration. We’re even headquartered in a town called Celebration. Our passion for celebrating what – and who – we appreciate should come in quite handy this year, as Disney Vacation Club rolls out Membership Magic, a vibrant array of Membership enhancements, exclusive experiences and special offers. -

2;Zwe#/'~ Reader 1: ~

Sahsbury Honors ColJege Honors Thesi An Honors Thesis Titled Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors Designation to the Honors College of Salisbury University in the Major Department of (h(>. v'l((.:f fr:< V1 \- by Signatures of Honors Thesis Committee Mentor: 2;Zwe#/'~ Reader 1: ~ Reader 2: ==~======~=============~===== Director: ~ _,._____________~-gnature - Print Running head: “AUTHENTICALLY DISNEY, DISTINCTLY CHINESE”: EXPLORING THE USE OF CULTURE IN DISNEY’S INTERNATIONAL THEME PARKS 1 “Authentically Disney, Distinctly Chinese”: Exploring the use of culture in Disney’s international theme parks Honors Thesis Frances Sherlock Salisbury University “AUTHENTICALLY DISNEY, DISTINCTLY CHINESE”: EXPLORING THE USE OF CULTURE IN DISNEY’S INTERNATIONAL THEME PARKS 2 “To all who come to this happy place, welcome. Shanghai Disneyland is your land. Here you leave today and discover imaginative worlds of fantasy, romance, and adventure that ignite the magical dreams within all of us. Shanghai Disneyland is authentically Disney and distinctly Chinese. It was created for everyone bringing to life timeless characters and stories in a magical place that will be a source of joy, inspiration, and memories for generations to come.” –Bob Iger (Shanghai Disneyland Resort Dedication taken from DAPS Magic, 2016) The Walt Disney Company’s newest international theme park venture, Shanghai Disneyland, promises to be different from previous international theme parks. Shanghai Disneyland promises to still be a Disney park but a Chinese Disney park. This distinction is important because in the past Disney has just reproduced its American parks within a host country assuming that what works in the United States would work in Tokyo, Paris, and Hong Kong. -

Disney Dream & Disney Fantasy Deck Plans

DISNEY DREAM & DISNEY FANTASY DECK PLANS STATEROOM AMENITIES Staterooms have tub/shower, flat-screen TV, ample closet space, in-room safe, hair CONCIERGE ROYAL SUITE CONCIERGE 1-BEDROOM SUITE CONCIERGE FAMILY OCEANVIEW DELUXE FAMILY OCEANVIEW DELUXE OCEANVIEW DELUXE FAMILY OCEANVIEW DELUXE OCEANVIEW DELUXE INSIDE STATEROOM STANDARD INSIDE WITH VERANDAH STATEROOM ( STATEROOM STATEROOM dryer, phone with voicemail messaging and WITH VERANDAH (Category R) (Category T) STATEROOM WITH VERANDAH STATEROOM WITH VERANDAH STATEROOM WITH VERANDAH Category 8) (Category 9) (Category 10) (Category 11) individual climate control. One master bedroom with queen- One bedroom with queen-size bed, (Category V) (Category 4) (Categories 5, 6 and 7) Queen-size bed, single Queen-size bed, single Queen-size bed, single Queen-size bed, single size bed, one wall pull-down double living area with double convertible Queen-size bed, double Queen-size bed, single convertible Queen-size bed, single convertible sofa, wall pull- convertible sofa, upper berth convertible sofa, upper berth convertible sofa, upper berth bed, and one wall pull-down single Exact amenities described may vary slightly sofa, one wall single pull-down bed in convertible sofa, upper berth pull- sofa, wall pull-down bed (in most) and convertible sofa, upper berth down bed (in most) or upper pull-down bed (in some), split pull-down bed (in some), split pull-down bed (in some), bath bed in living room, two bathrooms, living room, walk-in closets, whirlpool down bed, full bath with round tub upper berth pull-down bed (in some), pull-down bed (if sleeping four), berth pull-down bed (in some), bath with tub and shower. -

FALL 2010 Vol. 19 No. 3 Disney Files Magazine Is Published by the Good People at You May Be Wondering Why Our Cover’S on Fire

FALL 2010 vol. 19 no. 3 Disney Files Magazine is published by the good people at You may be wondering why our cover’s on fire. It’s a reasonable question, and I have Disney Vacation Club ® a (somewhat) reasonable answer. This issue is HOT! And not just Orlando-in-August P.O. Box 10350 Lake Buena Vista, FL 32830 hot. More like fireflies-with-a-fever hot. Laying-asphalt-in-a-wool-sweater hot. The-flat- screen-TV-someone-just-sold-me-at-a-discount-out-of-the-back-of-a-van hot. (Once again, I’ve said too much.) The point is, this magazine couldn’t be hotter if we’d soaked All dates, times, events and prices it in acid. That’s right, acid! (Kudos to those who caught that “It’s Tough to Be a Bug” printed herein are subject to reference. There’s another one on page 12, just for you.) The pages ahead are… change without notice. (Our lawyers do a happy dance when we say that.) Liquid-magma hot: Get an inside look at the “volcanic” creative concept for the expansive pool area at Disney’s new Hawai‘i resort (pages 3-4). MOVING? Update your mailing address McSteamy hot: Meet one of the firefighters charged with making sure special effects online at www.dvcmember.com don’t send Seattle Grace and other Disney production sets up in smoke (pages 5-6). Trendy hot: Track some of the latest Membership trends, as revealed in the 2009 MEMBERSHIP QUESTIONS? Condominium Association Survey (page 8). -

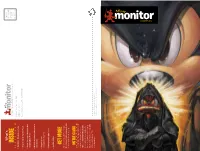

Monitrm Monitrm

Mickey What’s PRSRT STD U.S. POSTAGE mon® itr PAID The Walt Disney World Passholder Newsletter Disney INSIDE Destinations, LLC Disney Destinations, LLC • Star Wars™ Weekends returns PO Box 10045 Mickey • Step into an Enchanted Forest Lake Buena Vista, FL 32830-0045 monitSPRING 2012r • Stay in the story at Disney’s Art of Animation Resort Mickey Mickey • Meet Disney•Pixar’s adventurous new heroine monitWINTER 2012r monitSUMMER 2012r • Sing along with Sounds Like Summer • Disney Cruise Line News • And Much More GET MORE Add your email address to your pro- file atdsneyworld.com/passholder to enjoy extra-special benefits. ON THE COVER “Donald Maul” by Greg McCullough celebrates this year’s incredible edition of Star Wars Weekends. Greg has been associated with the event for many years, creating amazing artwork and even appearing at the event to present his original paintings. ©Disney WDWRES-PASS-12-22052 ©Disney/Lucasfilm Ltd. © 2012 Lucasfilm Ltd. & TM. Mickey SUMMER 2012 May (and June) the Force Be With You Star Wars™ Weekends returns May 18 to June 10, 2012 Set the coordinates on your navi-computer to Disney’s Hollywood Studios®. Because Star Wars Weekends will be there in full force, every Friday, Saturday and Sunday from May 18 to June 10, 2012. This year, the intergalactic event will focus on Episode I: The Phantom Menace, which recently lit up theater screens in eye-popping 3-D. Most of the event’s celebrity lineup—including Jake Lloyd (Young Anakin)—will represent Episode I. Additionally, Star Wars Weekends will feature some of the favorite characters from the film, including Darth Maul, Mace Windu, Queen Amidala, Aurra Sing and of course, C-3PO and R2-D2. -

Theme Park Fandom Theme Park Fandom

TRANSMEDIA Williams Theme Fandom Park Rebecca Williams Theme Park Fandom Spatial Transmedia, Materiality and Participatory Cultures FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Theme Park Fandom FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Transmedia: Participatory Culture and Media Convergence The book series Transmedia: Participatory Culture and Media Convergence provides a platform for cutting-edge research in the field of media studies, with a strong focus on the impact of digitization, globalization, and fan culture. The series is dedicated to publishing the highest-quality monographs (and exceptional edited collections) on the developing social, cultural, and economic practices surrounding media convergence and audience participation. The term ‘media convergence’ relates to the complex ways in which the production, distribution, and consumption of contemporary media are affected by digitization, while ‘participatory culture’ refers to the changing relationship between media producers and their audiences. Interdisciplinary by its very definition, the series will provide a publishing platform for international scholars doing new and critical research in relevant fields. While the main focus will be on contemporary media culture, the series is also open to research that focuses on the historical forebears of digital convergence culture, including histories of fandom, cross- and transmedia franchises, reception studies and audience ethnographies, and critical approaches to the culture industry and commodity