“Dashes of American Humor” Howard Paul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

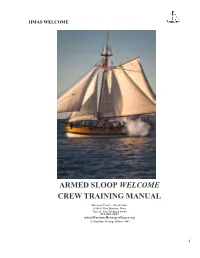

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

Voy Ages and Travels. London

FRAGMENTS OF VOY AGES AND TRAVELS. LONDON: J. 1\IOYES, CASTLE STnEET, LF.JCf.s'l'.~R SQUA}tF,. FRAGMENTS OF VOYAGES AND TRAVELS. By CAPTAIN BASIL HALL, R.N. F.R.S. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL. n. ROBERT CA DELL, EDiNBURGH; WHITTAKER, TRE,\CHER, lit co. LONDON. M.DCCC.XXXIIl. G- ~·1D 1-1/ b J R 33 CQNTENTS OF VI V·')... pAGE EXCURSION TO CANDELAY LAKE IN CEYLON 1 GRIFFINS IN INDIA - SINBAD'S VALLEY OF DIAMONDS-A MOSQUITO HUNT.... •••••• 34 CEYLONESE CANOES-PERUVIAN BALSAS-THE FLOATING WINDLASS OF THE COROMANDEL FISHERMEN •••••••••••••••••••••••••• 68 TilE SURF AT MADRAS ••••••••••••••••••• , 100 TilE SUNNYASSES •••••••••••••••••••••••• 128 PALANKEEN TRAVELLING-IRRIGATING TANKS IN TIlE MYSORE COUNTRY •••••••••••••• 146 THE DESSERA FESTIVAL AT MYSORE 191 GRANITE MOUNTAIN CUT INTO A STATUE- BAMBOO FOREST-RAJAH OF COORG ••••• 232 VISIT TO TilE SULTAN OF PONTIANA, IN BORNEO - SIR SAMUEL HOOD •••••••••••••••••• 270 FRAGMENTS OF VOYAGES AND TRAVELS. CHAPTER I. EXCURSION TO CANDELAY LAKE IN CEYLON. THE fervid activity of our excellent admi ral, Sir Samuel Hood, in whose flag-ship I served as lieutenant from ]812 to 1815 on the Indian station, furnished abundant materials for journal-writing, had we only known how to profit by them. There was ever observable a boyish hilarity about this great officer which made it equally delightful to serve officially under him, and to enjoy his friendly companionship; in either case, we always felt certain of making the most of our opportunities. VOL. n.-SERIES Ill. B 2 FRAGMENTS OF Scarcely, t'hel'efore, had we returned from the alligator hunt, near Trincomalee, which I have already described, when Sir Samuel applied himself to the collector of the district, who was chief civilian of the place, and begged to know what he would recommend us to see next . -

Dictionary.Pdf

THE SEAFARER’S WORD A Maritime Dictionary A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Ranger Hope © 2007- All rights reserved A ● ▬ A: Code flag; Diver below, keep well clear at slow speed. Aa.: Always afloat. Aaaa.: Always accessible - always afloat. A flag + three Code flags; Azimuth or bearing. numerals: Aback: When a wind hits the front of the sails forcing the vessel astern. Abaft: Toward the stern. Abaft of the beam: Bearings over the beam to the stern, the ships after sections. Abandon: To jettison cargo. Abandon ship: To forsake a vessel in favour of the life rafts, life boats. Abate: Diminish, stop. Able bodied seaman: Certificated and experienced seaman, called an AB. Abeam: On the side of the vessel, amidships or at right angles. Aboard: Within or on the vessel. About, go: To manoeuvre to the opposite sailing tack. Above board: Genuine. Able bodied seaman: Advanced deckhand ranked above ordinary seaman. Abreast: Alongside. Side by side Abrid: A plate reinforcing the top of a drilled hole that accepts a pintle. Abrolhos: A violent wind blowing off the South East Brazilian coast between May and August. A.B.S.: American Bureau of Shipping classification society. Able bodied seaman Absorption: The dissipation of energy in the medium through which the energy passes, which is one cause of radio wave attenuation. Abt.: About Abyss: A deep chasm. Abyssal, abysmal: The greatest depth of the ocean Abyssal gap: A narrow break in a sea floor rise or between two abyssal plains. -

Download ROYAL W INT 11 FORE M. RIGGING

Euromodel Royal William.11.Ship’s Boat. September 2021 TRANSLATION LINKS 1. type into your browser ... english+italian+glossary+nautical terms 2. utilise the translation dictionary ‘Nautical Terms & Expressions’ from Euromodel website An interpretive review of the Royal William 1st. Rate English Vessel Originally launched in 1670 as the 100-gun HMS Prince Re-built and launched in 1692 as the HMS Royal William Finally re-built again and ... Launched 1719 Checked the Scale 1:72 Essential Resource Information File ? 11.SHIP’S BOAT September 2021 This paper is based on the supplied drawings, external references, kit material – and an amount of extra material. It serves to illustrate how this ship might be built.The leve l of complexity chosen is up to the individual This resource information was based on the original text supplied by Euromodel and then expanded in detail as the actual ship was constructed by MSW member piratepete007. [Additional & exceptional support was gratefully received from MSW members marktiedens, Ken3335, Denis R, Keith W, Vince P & Pirrozzi. My sincere thanks to them and other MSW members who gave advice and gave permission to use some of their posted photos. Neither the author or Euromodel have any commercial interest in this information and it is published on the Euromodel web site in good faith for other persons who may wish to build this ship. Euromodel does not accept any responsibility for the contents that follow. 1 Euromodel Royal William.11.Ship’s Boat. September 2021 This is not an instructional manual but is a collaboration amongst a number of MSW members whose interpretations were based on the drawings and the supplied kit. -

Glossary of Terms (List Will Be Updated on a Continual Basis)

Glossary of Terms (list will be updated on a continual basis) The words below are new to our Glossary of Terms. These words will be integrated into our overall list, which is below the new words. Chafing Gear – pads, mats, ropes and other materials tied around pieces of rigging to protect them from rubbing on spars and other parts of the rig Foxes – pieces of scrap line made by twisting together several strands or yarns Hand, Reef & Steer – traditional qualifications of an able seaman, to hand is to take in or furl a sail and to reef is to shorten sail and to steer is to take a turn at the helm Helmsman – the Sailor stationed at the ship’s helm (wheel) in charge of steering and keeping a straight course Marline – light, two-stranded line; often tarred and used for seizings Marlinespike – a tapered metal spike used to separate strands of rope, untie knots and as a handle for hauling away on seizings, whippings, etc. Merchant Service – the industry concerned with commercial shipping ventures (i.e., non-military) Rating – denotes a Sailor’s rank, responsibilities and rate of pay (i.e., able seaman, ordinary seaman, boy, etc.) Rigging – the lines and ropes that hold the masts, spars and sails Sail Making – the work of mending, replacing and sewing sails; the sail maker would often advise on how best to set and trim sails Seizing – method of binding two ropes or objects together involving wrapping them tightly with line Splice – weaving together to strands of separate ropes to form one longer rope Watches – division of labor aboard ship; the -

The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Linfield Alumni Book Gallery Linfield Alumni Collections 2019 Dreamers before the Mast: The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris John Kerr Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/lca_alumni_books Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kerr, John, "Dreamers before the Mast: The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris" (2019). Linfield Alumni Book Gallery. 1. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/lca_alumni_books/1 This Book is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Book must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Dreamers Before the Mast, The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris By John Kerr Carol Lew Simons, Contributing Editor Cover photo by Shep Root Third Edition This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/4.0/. 1 PREFACE AND A TRIBUTE TO REGINA Steven Katona Somehow wood, steel, cable, rope, and scores of other inanimate materials and parts create a living thing when they are fastened together to make a ship. I have often wondered why ships have souls but cars, trucks, and skyscrapers don’t. -

A Few Hours' Experience with a Typhoon in the China Sea

~ 11t<11 ~ A Few Hours' Experience with a Typhoon in the China Sea BY FREDERIC HINCKLEY BOSTON : FISH PRINTING COMPANY 1900 rt~ ~y 1t;<l1 A Few Hours' Experience with a Typhoon in the China Sea , BY FREDERIC HINCKLEY BOSTON : FISH PRINTING COMPANY 1900 A FEW HOURS' EXPERIENCE WITH A TYPHOON IN THE CHINA SEA. ·· ROFESSOR WILLIAMS of Yale College, in his P excellent and most exhaustive work on China, called " The Middle Kingdom," writes as follows of the storms there : "The increased temperature on the southern coast of China during the months of June and July operates, with other causes, to produce violent storms, along the sea board, called tyfoons, a. word derived from the Chinese 'tafung,' or 'great wind.' These destructive tornadoes occur from Hainan to Chusan, between July and October, gradually progressing northward as the season advances, and diminishing in fury in the higher latitudes. They annually occasion great 19sses to the native and foreign shipping in Chinese waters, more than half the sailing ships lost on that coast having suffered in them. Happily, their fury is oftenest spent at sea, but when they occur inland, the loss of life is fearful. In August, 1862, and Sept. 21, 187 4, the deaths reported in two such storms near Can ton, Hong Kong, and their vicinity, were upwards of thirty thousand each. In the latter instance the American steamer ' Alaska,' of thirty-five hundred tons, was lifted Some four days previous she had left her moorings in from her anchorage and gently put down in five feet of Pearl River, just below Whampoa, with a full cargo of water near the shore, from which she was safely floated tea bound to New York. -

The Art of Sail-Making

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com Theartofsail-making Art J^S. /10<f. I X 8 i I 1 6- THE ART SAIL-MAKING, AS PRACTISED IN ©De Bogal Kali!?, AND ACCORDING TO THE MOST APPROVED METHODS IN THE ACCOMPANIED WITH THE PARLIAMENTARY REGULATIONS RELATIVE TO SAILS AND SAIL-CLOTH ; €!je atrmiraltj} Instructions for MANUFACTURING CANVAS FOR HER MAJESTY'S NAVY, Form of Tender, g-c. ILLUSTRATED BY NUMEROUS FIGURES, WITH FULL AND ACCURATE TABLES. - .'"'.- ?i?> THE FOURTH EDITION, ''"?-/. CORRECTED AND IMPROVED. — {'o LONDON: PRINTED FOR CHARLES WILSON, (Late J. W. Norie and Wilson,) CHARTSELLER TO THE ADMIRALTY, THE HON. EAST INDIA COMPANY, AND CORPORATION OP TRINITY HOUSE, At tbe Navigation Warehouse and Naval Academy, No. 157, LEADENHALL STREET. 1843. Entered at Stationers' Hall. 1. Dennett, Printer, 121, Fleet Street. PREFACE. The following Treatise on Sail-making was first pub lished in " The Elements and Practice of Rigging, Seamanship, Naval Tactics," &c. &c. a work in two volumes quarto. As an object of particular convenience and advan tage to Naval Artists, the then proprietor had been solicited to separate the arts there treated of, and to pub lish them in a smaller form. In compliance with this request, the work was re-published in four volumes octavo, with a separate volume of plates. The first edition of the Art of Sail-making was pro duced in the present form, and met with a favourable reception, from the merits of its correct delineation and clear description ; by these its utility was felt, and its value justly appreciated of greater import. -

Logbook of the United States Frigate Constitution Isaac Hull, Commander June 12, 1812 - September 16, 1812

TRANSCRIPTION OF Logbook of The United States Frigate Constitution Isaac Hull, Commander June 12, 1812 - September 16, 1812 Original logbook available at “Logbook of the U.S.S. Constitution”, Volume 3, February 1, 1812 – December 13, 1813. Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Record Group 24. (Microform publication M1030, T508, Roll 1, Target 3) National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. © 2018 USS Constitution Museum | usscm.org The United S. Frigate Constitution Isaac Hull Esqr. Commander Issued 278 lbs of Bread Remarks on board Friday June 12th 1812 Alexandria 40 lbs of Butter 80 lbs Commenced with light airs from the Northward, and Westward, and clear at 1 PM moored Ship with 70 fms of the Starboard Bower, and 30 fms of Cheese 20 Gall of of Larboard Bower furled sails, and made all snug, throughout the night pleasant with Light airs from the Northwards and Westward Received Rice 20 Galls of Spirits from the Recruiting Officer at Philadelphia the following Men vizt. [blank] Received on board from the Navy Yard two 9 Inch Hawsers, some of 20 Gallons of Molasses our Spare rigging swabs &c which had been left at the Yard Filled the Ground Tier with water at Meridien pleasant breezes from the Northward, Received on board and Eastward and clear Thirty six marines with two Commissioned officers The United S. Frigate Constitution Isaac Hull Esqr. Commander Saturday Commences with a light breeze from the Northward, and Eastward, and clear bending the Mizin staysail flying Jibb Studding sails &c throughout June 13th 1812 the night Pleasant, with moderate breezes from the Southwards, and Westwards. -

Logbook of the United States Frigate Constitution Charles Stewart, Commander December 31, 1813 - April 3

TRANSCRIPTION OF Logbook of The United States Frigate Constitution Charles Stewart, Commander December 31, 1813 - April 3. 1814 December 18, 1814 - May 16, 1815 Original logbooks available at “Logbook of the U.S.S. Constitution”, Volume 4, December 31, 1813 – April 3, 1814, and December 18, 1814 – May 16, 1815. Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Record Group 24. (Microform publication M1030, T508, Roll 1, Target 3) National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. © 2018 USS Constitution Museum | usscm.org H. K. F. Courses. Winds. Friday, December 31. 1813. 1 NNE Commences with clear weather and strong breezes from the Westwards. At 1 P.M unmoored Ship. At 3 got under way. 2 At half past 4 past Boston light. At three quarters past 4 discharged the Pilot. At 5 Boston light bore W. by. N. ½. N. 3 distant five miles. At 5 set top-gallant sails. At 7 took in top gallant sails. At half past 7 Thatcher’s Island light bore 4 N.W. by W. distant two leagues. At three quarters past 7 took two reefs in the Mizen top-sail. At 9 Set Fore and Main top gallant sails. At half past 9 set the Spanker; fresh breezes and cloudy weather. At half past 11 brailed up the 5 spanker. At midnight took in top gallant sails; fresh breezes and cloudy. At half past 12 A.M. set the Main top gallant 6 10 4 N.E. N.W. sails. At 2 took in main top gallant sail. At 4 turned the reefs out of the top sail and set Fore and Main top gallant sails. -

Ship 'Timandra' Log-Book

Pandora Research www.nzpictures.co.nz Ship ‘Timandra’ Log-book Archives NZ Reference AAYZ 8982 NZC 34/9/10 (partial transcript) A Log-book containing the proceedings on board the “Timandra” from the Port of London to New Plymouth, New Zealand commencing 21 Sep 1841 and ending 10 Mar 1842 – Captain Skinner. 1841 Sep 21 Tue This day commences with moderate breezes from the westward and cloudy weather. Employed painting the masts & Sunday jobs about the decks. Two joiners employed for ¾ of a day. Received on board 50 water casks 150 gallons each. 1841 Sep 22 Wed This day throughout moderate breezes &c. Cloudy weather. Employed necessarily about the decks and painting the lower masts. Two joiners employed for the whole day. 1841 Sep 23 Thu This day throughout fresh breezes & cloudy. Employed clearing away the ‘tween decks for the joiners &c. The remainder of this day fine weather. Two joiners employed in the Cabin. Several joiners employed fitting the Berths in the ‘tween decks from the New Zealand Company. 1841 Sep 24 Fri This commences with fresh breezes and heavy rains. Washing and cleaning ship & sundry necessary jobs in the hold. Two joiners employed for the whole day. 1841 Sep 25 Sat This day commences with moderate breezes & cloudy weather with showers of rain. Took on 34 water casks 150 gallons each. The remainder of this day showery weather. Cleaning and washing the ship. Carpenter variously employed making skeads &c. Two joiners employed in the cabin. Morning Advertiser 25 Sep 1841 Shipping Intelligence – Entered Outwards for Loading, Sept 24. -

Ship Modeling Simplified

58 PART III Masting and Rigging "The rigging of a ship consists of a quantity of Ropes, or Cordage, of various dimensions, for the support of the Masts and Yards. Those which are fixed and stationary, such as Shrouds, Stays, and Back-stays, are termed Standing Rigging; but those which reeve through Blocks, or Sheave-Holes, are denominated Running Rigging; such as Haliards, Braces, Clew-lines, Buntlines, &c. &c. These are occasionally hauled upon, or let go, for the purpose of working the Ship." — The Young Sea Officer's Sheet Anchor, 1819 the animal skin he hung to catch the GETTING STARTED wind was pushing him along. The physi- The quest for the perfect blend of masts cal principles behind the concept of and sails began the moment it dawned using wind and sail to produce motion on primitive mariners that they could are simple. But adapting those principles harness the wind and — sans sweat — has led to a chase that will give aspiring move their boats through the water. The model builders an infinite variety of styles evolution continues today, with sailors to pursue. using computer-designed sails and Animal skins eventually gave way to modern alloy spars to squeeze the most more pliable materials — papyrus, and from wind and craft. flax, then woven cloth. And as boats Cutting the waves on a downwind became bigger, so too did the sails — run, the first sailor likely had no idea why which sailors expanded by sewing strips 59 of cloth together. Canvas became the shipwrights developed standing rigging. cloth of choice.