Congenital Melanocytic Nevi: Where Are We Now?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Features of Benign Tumors of the External Auditory Canal According to Pathology

Central Annals of Otolaryngology and Rhinology Research Article *Corresponding author Jae-Jun Song, Department of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College of Clinical Features of Benign Medicine, 148 Gurodong-ro, Guro-gu, Seoul, 152-703, South Korea, Tel: 82-2-2626-3191; Fax: 82-2-868-0475; Tumors of the External Auditory Email: Submitted: 31 March 2017 Accepted: 20 April 2017 Canal According to Pathology Published: 21 April 2017 ISSN: 2379-948X Jeong-Rok Kim, HwibinIm, Sung Won Chae, and Jae-Jun Song* Copyright Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College © 2017 Song et al. of Medicine, South Korea OPEN ACCESS Abstract Keywords Background and Objectives: Benign tumors of the external auditory canal (EAC) • External auditory canal are rare among head and neck tumors. The aim of this study was to analyze the clinical • Benign tumor features of patients who underwent surgery for an EAC mass confirmed as a benign • Surgical excision lesion. • Recurrence • Infection Methods: This retrospective study involved 53 patients with external auditory tumors who received surgical treatment at Korea University, Guro Hospital. Medical records and evaluations over a 10-year period were examined for clinical characteristics and pathologic diagnoses. Results: The most common pathologic diagnoses were nevus (40%), osteoma (13%), and cholesteatoma (13%). Among the five pathologic subgroups based on the origin organ of the tumor, the most prevalent pathologic subgroup was the skin lesion (47%), followed by the epithelial lesion (26%), and the bony lesion (13%). No significant differences were found in recurrence rate, recurrence duration, sex, or affected side between pathologic diagnoses. -

CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal

Int. Adv. Otol. 2009; 5:(3) 401-403 CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal: A Case Report Sedat Ozturkcan, Ali Ekber, Riza Dundar, Filiz Gulustan, Demet Etit, Huseyin Katilmis Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery ‹zmir Atatürk Research and Training Hospital, Ministry of Health, ‹ZM‹R-TURKEY (SO, AE, FG, DE, HK) Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery Etimesgut Military Hospital , ANKARA-TURKEY (RD) Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in humans; however, its occurrence in the external auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon. The clinical manifestations of pigmented nevus of the EAC have been reported to include ear fullness, foreign body sensation, hearing impairment, and otalgia, but some cases were asymptomatic and were found incidentally. The treatment of choice for a symptomatic intradermal nevus in the EAC is complete excision. There has been no recurrence reported in the literature . A pedunculated, papillomatous hair-bearing lesion was detected in the external auditory canal of the patient who was on follow-up for pruritus. Clinical and pathologic features of an intradermal nevus of the external auditory canal are presented, and the literature reviewed. Submitted : 14 October 2008 Revised : 01 July 2009 Accepted : 09 July 2009 Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in left external auditory canal. Otomicroscopic humans; however, its occurrence in the external examination revealed a pedunculated, papillomatous auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon [1-4]. Intradermal hair-bearing lesion in the postero-inferior cartilaginous nevus is considered to be a form of benign cutaneous portion of the external auditory canal (Figure 1). -

Acral Compound Nevus SJ Yun S Korea

University of Pennsylvania, Founded by Ben Franklin in 1740 Disclosures Consultant for Myriad Genetics and for SciBase (might try to sell you a book, as well) Multidimensional Pathway Classification of Melanocytic Tumors WHO 4th Edition, 2018 Epidemiologic, Clinical, Histologic and Genomic Aspects of Melanoma David E. Elder, MB ChB, FRCPA University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA Napa, May, 2018 3rd Edition, 2006 Malignant Melanoma • A malignant tumor of melanocytes • Not all melanomas are the same – variation in: – Epidemiology – risk factors, populations – Cell/Site of origin – Precursors – Clinical morphology – Microscopic morphology – Simulants – Genomic abnormalities Incidence of Melanoma D.M. Parkin et al. CSD/Site-Related Classification • Bastian’s CSD/Site-Related Classification (Taxonomy) of Melanoma – “The guiding principles for distinguishing taxa are genetic alterations that arise early during progression; clinical or histologic features of the primary tumor; characteristics of the host, such as age of onset, ethnicity, and skin type; and the role of environmental factors such as UV radiation.” Bastian 2015 Epithelium associated Site High UV Low UV Glabrous Mucosa Benign Acquired Spitz nevus nevus Atypical Dysplastic Spitz Borderline nevus tumor High Desmopl. Low-CSD Spitzoid Acral Mucosal Malignant CSD melanoma melanoma melanoma melanoma melanoma 105 Point mutations 103 Structural Rearrangements 2018 WHO Classification of Melanoma • Integrates Epidemiologic, Genomic, Clinical and Histopathologic Features • Assists -

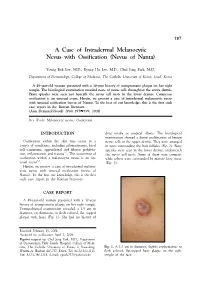

A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta)

197 A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta) Young Bok Lee, M.D., Kyung Ho Lee, M.D., Chul Jong Park, M.D. Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea A 49-year-old woman presented with a 30-year history of asymptomatic plaque on her right temple. The histological examination revealed nests of nevus cells throughout the entire dermis. Bony spicules were seen just beneath the nevus cell nests in the lower dermis. Cutaneous ossification is an unusual event. Herein, we present a case of intradermal melanocytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. (Ann Dermatol (Seoul) 20(4) 197∼199, 2008) Key Words: Melanocytic nevus, Ossification INTRODUCTION drug intake or medical illness. The histological examination showed a dense proliferation of benign Ossification within the skin may occur in a nevus cells in the upper dermis. They were arranged variety of conditions, including pilomatricoma, basal in nests surrounding the hair follicles (Fig. 2). Bony cell carcinoma, appendageal and fibrous prolifera- spicules were seen in the lower dermis, underneath 1,2 tion, inflammation and trauma . The occurrence of the nevus cell nests. Some of them were compact ossification within a melanocytic nevus is an un- while others were surrounded by mature fatty tissue 3-5 usual event . (Fig. 3). Herein, we present a case of intradermal melano- cytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. -

Acquired Bilateral Nevus of Ota–Like Macules (Hori's Nevus): a Case

Acquired Bilateral Nevus of Ota–like Macules (Hori’s Nevus): A Case Report and Treatment Update Jamie Hale, DO,* David Dorton, DO,** Kaisa van der Kooi, MD*** *Dermatology Resident, 2nd year, Largo Medical Center/NSUCOM, Largo, FL **Dermatologist, Teaching Faculty, Largo Medical Center/NSUCOM, Largo, FL ***Dermatopathologist, Teaching Faculty, Largo Medical Center/NSUCOM, Largo, FL Abstract This is a case of a 71-year-old African American female who presented with bilateral periorbital hyperpigmentation. After failing treatment with a topical retinoid and hydroquinone, a biopsy was performed and was consistent with acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules, or Hori’s nevus. A review of histopathology, etiology, and treatment is discussed below. cream and tretinoin 0.05% gel. At this visit, a Introduction Figure 2 Acquired nevus of Ota-like macules (ABNOM), punch biopsy of her left zygoma was performed. or Hori’s nevus, clinically presents as bilateral, Histopathology reported sparse proliferation blue-gray to gray-brown macules of the zygomatic of irregularly shaped, haphazardly arranged melanocytes extending from the superficial area. It less often presents on the forehead, upper reticular dermis to mid-deep reticular dermis outer eyelids, and nose.1 It is most common in women of Asian descent and has been reported Figure 4 in ages 20 to 70. Classically, the eye and oral mucosa are uninvolved. This condition is commonly misdiagnosed as melasma.1 The etiology of this condition is not fully understood, and therefore no standardized treatment has been Figure 3 established. Case Report A 71-year-old African American female initially presented with a two week history of a pruritic, flaky rash with discoloration of her face. -

Short Course 11 Pigmented Lesions of the Skin

Rev Esp Patol 1999; Vol. 32, N~ 3: 447-453 © Prous Science, SA. © Sociedad Espafiola de Anatomfa Patol6gica Short Course 11 © Sociedad Espafiola de Citologia Pigmented lesions of the skin Chairperson F Contreras Spain Ca-chairpersons S McNutt USA and P McKee, USA. Problematic melanocytic nevi melanin pigment is often evident. Frequently, however, the lesion is solely intradermal when it may be confused with a fibrohistiocytic RH. McKee and F.R.C. Path tumor, particularly epithelloid cell fibrous histiocytoma (4). It is typi- cally composed of epitheliold nevus cells with abundant eosinophilic Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, cytoplasm and large, round, to oval vesicular nuclei containing pro- USA. minent eosinophilic nucleoli. Intranuclear cytoplasmic pseudoinclu- sions are common and mitotic figures are occasionally present. The nevus cells which are embedded in a dense, sclerotic connective tis- Whether the diagnosis of any particular nevus is problematic or not sue stroma, usually show maturation with depth. Less frequently the nevus is composed solely of spindle cells which may result in confu- depends upon a variety of factors, including the experience and enthusiasm of the pathologist, the nature of the specimen (shave vs. sion with atrophic fibrous histiocytoma. Desmoplastic nevus can be distinguished from epithelloid fibrous histiocytoma by its paucicellu- punch vs. excisional), the quality of the sections (and their staining), larity, absence of even a focal storiform growth pattern and SiQO pro- the hour of the day or day of the week in addition to the problems relating to the ever-increasing range of histological variants that we tein/HMB 45 expression. -

Optimal Management of Common Acquired Melanocytic Nevi (Moles): Current Perspectives

Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW Optimal management of common acquired melanocytic nevi (moles): current perspectives Kabir Sardana Abstract: Although common acquired melanocytic nevi are largely benign, they are probably Payal Chakravarty one of the most common indications for cosmetic surgery encountered by dermatologists. With Khushbu Goel recent advances, noninvasive tools can largely determine the potential for malignancy, although they cannot supplant histology. Although surgical shave excision with its myriad modifications Department of Dermatology and STD, Maulana Azad Medical College and has been in vogue for decades, the lack of an adequate histological sample, the largely blind Lok Nayak Hospital, New Delhi, Delhi, nature of the procedure, and the possibility of recurrence are persisting issues. Pigment-specific India lasers were initially used in the Q-switched mode, which was based on the thermal relaxation time of the melanocyte (size 7 µm; 1 µsec), which is not the primary target in melanocytic nevus. The cluster of nevus cells (100 µm) probably lends itself to treatment with a millisecond laser rather than a nanosecond laser. Thus, normal mode pigment-specific lasers and pulsed ablative lasers (CO2/erbium [Er]:yttrium aluminum garnet [YAG]) are more suited to treat acquired melanocytic nevi. The complexities of treating this disorder can be overcome by following a structured approach by using lasers that achieve the appropriate depth to treat the three subtypes of nevi: junctional, compound, and dermal. Thus, junctional nevi respond to Q-switched/normal mode pigment lasers, where for the compound and dermal nevi, pulsed ablative laser (CO2/ Er:YAG) may be needed. -

Case Report of Giant Congenital Melanocytic Nevus

PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY Series Editor: Camila K. Janniger, MD Bathing Trunks Nevus: Case Report of Giant Congenital Melanocytic Nevus Ronald Russ, DO; Lisa Light, MS-IV Bathing trunks nevi, a subtype of giant congeni- 34 years. All maternal and prenatal history was unre- tal melanocytic nevi (CMN), are skin tumors that markable. Upon initial physical examination as a new- present by 2 years of age and occur in a low born (1 hour following delivery), the infant had a large percentage of all births. We report a case of (≥5% body surface area), circumferentially pigmented bathing trunks nevus that was initially suspected area from the umbilicus to mid thigh bilaterally to be melanoma, and describe the history, patho- (Figure 1). Interposed darkened lesions were pres- physiology, and treatment options for CMN. We ent, with 3 distinct, raised, lipomatous-type nodules also discuss the risk for neurocutaneous melano- (2 cm, 1.3 cm, and 3 cm in diameter from left to right) sis (NCM), which is a rare syndrome in patients over the lower lumbar spine (Figure 2). There were no with giant CMN. signs of jaundice, hemolysis, meningomyelocele, or Cutis. 2009;83:69-72. abnormal hair growth. The rest of the physical exami- nation was unremarkable, including cardiovascular, pulmonary, and abdominal systems, and genitourinary athing trunks nevus is a specific subtype of functioning was normal. Cord blood testing revealed giant congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN) A Rh-positive blood type, and a direct Coombs test B with spread resembling bathing trunks. This was negative for antibodies. Complete blood cell rare variant is clinically significant because of the count was within reference range, with the excep- increased risk for progression to melanoma and its tion of a low platelet count of 2343103/µL (reference association with neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM).1 range, 250–4503103/µL). -

Acral Melanoma Toshiaki Saida, Hiroshi Koga, Yoriko Yamazaki, Masaru Tanaka IV.2

Chapter IV.2 Acral Melanoma Toshiaki Saida, Hiroshi Koga, Yoriko Yamazaki, Masaru Tanaka IV.2 Contents thickness, biological behavior is not different among the four histogenetic types [16]. More- IV.2.1 Definition . .196 over, cutaneous melanomas not infrequently IV.2 IV.2.2 Clinical Features . .197 show overlapping histopathological features of IV2.3 Dermoscopic Criteria. 198 the four types [36]. Ackerman repeatedly criti- cized the validity of the Clark’s classification IV.2.4 Relevant Clinical Differential and proposed the unifying concept of melano- Diagnosis. 198 ma [1]. IV.2.5 Histopathology. .199 Recently, Bastian and co-workers defined ac- ral melanoma as melanoma occurring on the IV.2.6 Management. .200 non-hair-bearing skin of the palms or soles or IV.2.7 Case Study. .200 under the nails and found that this type of mel- References. .202 anoma was unique in frequent amplifications of chromosomes 5p15, 5p13, 11q13, and 12q14 [4, 7]. Particularly, amplification of 11q13 was de- tected in ~50% of this type of melanoma. Cyclin D1 is the most important candidate gene located in this chromosome region. It is noteworthy IV.2.1 Definition that 5 of 36 acral melanomas defined by Bastian and co-workers were superficial spreading mel- Acral melanoma is a melanoma that affects ac- anoma according to Clark’s classification [7]. ral areas of the skin, which is the most prevalent Another characteristic of acral melanoma is site of melanoma in non-Caucasians [5, 10]. very low rate of mutation of the BRAF onco- Strictly speaking, acral lentiginous melanoma is gene, which is commonly found in superficial not a synonym for acral melanoma. -

Congenital Melanocytic Nevus

BCCH Pediatric Dermatology Clinic Joseph M Lam, MD CONGENITAL MELANOCYTIC NEVUS What is a congenital melanocytic nevus? A "congenital melanocytic nevus" (aka mole) is the name for a common brown birthmark which is made up of special pigment-producing cells. The size of the birthmark may range from a small 1 cm mark to a giant birthmark covering half of the body or more. How common are congenital melanocytic nevus? Small congenital pigmented moles (brown birthmarks) are seen in 1 percent of all healthy newborn babies. Giant congenital moles (larger than 8 inches) are rare, found in fewer than one in 20,000 newborn infants. Why are they special? Small- and medium-sized congenital moles may rarely develop melanoma, a worrisome form of skin cancer. However, the risk of this happening is less than 1% and in adults, the risk of developing skin cancer in any area of the skin is much higher than the risk of melanoma in a small or medium-sized congenital mole. However, depending upon the appearance of the mole, its location and the ease of removal, we may suggest that the mole be taken out or we may recommend keeping the mole and just paying attention to any changes in the mole. Rarely, mole cells can be present in the brain - this happens in patients with many ‘satellite’ moles. If this causes problems, the problems usually show up in the first few months of life. It is important to inspect congenital moles on a regular basis at home. We may also recommend that some moles be observed in the office with pictures. -

A Nevus of OTA with Intraoral Involvement: a Rare Case Report

Shivare P. et al.: Nevus of OTA- a rare entity CASE REPORT A Nevus of OTA with Intraoral Involvement: A Rare Case Report Peeyush Shivhare1, Lata S.2, Monu Yadav3, Naqoosh Haidry4, Shruthi T. Patil5 1,5- Senior lecturer department of oral medicine and radiology, Narsinhbhai patel dental college and hospital, Visnagar, Gujarat. 2- Professor and head of the department, Rungta Correspondence to: College Of Dental Sciences And Research, Bhilai, Chhattisgarh. 3- PG student. Dr. Peeyush Shivhare Senior lecturer department of Department Of Oral Medicine And Radiology, Carrier Dental College And Hospital. oral medicine and radiology, Narsinhbhai patel dental Lucknow. 4- Senior lecturer department of maxillofacial surgery, Narsinhbhai patel college and hospital, Visnagar, Gujarat. dental college and hospital, Visnagar, Gujarat. Contact Us: www.ijohmr.com ABSTRACT Nevus of Ota, which originally was described by Ota and Tanino in 1939. It is characterized as congenital or acquired hamartoma of dermal melanocytes, presents clinically as a blue or gray patch on the face within the distribution of the ophthalmic and maxillary branches of the fifth cranial (trigeminal) nerve. Involvement of the palatal mucosa occurs rarely in nevus of Ota, when it occurs, it usually blends with the oral mucosa and is typically irregular, ill defined and often present as a mottled patch. Nevus of Ota is rare in the Indian subcontinent. So far very less cases of nevus of ota with intraoral involvement have been documented in the English literature. We report a rare case of intraoral nevus of Ota in a 20 year-old female patient. KEYWORDS: Nevus of Ota, Melanoma, Hamartoma, Glaucoma AA aaaasasasss INTRODUCTION The nevus of Ota (nevus fuscoceruleus ophthal- momaxillaris” or oculodermal melanocytosis) is a macular discoloration of the face, found most commonly in the Japanese people.1 Nevus of ota develops when the melanocyte get entrapped in the upper third of the dermis. -

Acral Melanoma

Accepted Date : 07-Jul-2015 Article type : Original Article The BRAAFF checklist: a new dermoscopic algorithm for diagnosing acral melanoma Running head: Dermoscopy of acral melanoma Word count: 3138, Tables: 6, Figures: 6 A. Lallas,1 A. Kyrgidis,1 H. Koga,2 E. Moscarella,1 P. Tschandl,3 Z. Apalla,4 A. Di Stefani,5 D. Ioannides,2 H. Kittler,4 K. Kobayashi,6,7 E. Lazaridou,2 C. Longo,1 A. Phan,8 T. Saida,3 M. Tanaka,6 L. Thomas,8 I. Zalaudek,9 G. Argenziano.10 Article 1. Skin Cancer Unit, Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova IRCCS, Reggio Emilia, Italy 2. Department of Dermatology, Shinshu University School of Medicine, Matsumoto, Japan 3. Department of Dermatology, Division of General Dermatology, Medical University, Vienna, Austria 4. First Department of Dermatology, Medical School, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece 5. Division of Dermatology, Complesso Integrato Columbus, Rome, Italy 6. Department of Dermatology, Tokyo Women’s Medical University Medical Center East, Tokyo, Japan 7. Kobayashi Clinic, Tokyo, Japan 8. Department of Dermatology, Claude Bernard - Lyon 1 University, Centre Hospitalier Lyon-Sud, Pierre Bénite, France. 9. Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Medical University, Graz, Austria 10. Dermatology Unit, Second University of Naples, Naples, Italy. This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as Accepted doi: 10.1111/bjd.14045 This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Please address all correspondence to: Aimilios Lallas, MD.