Case Report of Giant Congenital Melanocytic Nevus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLAPA Adults Conference

Adults Cleft Conference Camden Lock, London, England Saturday 17 November 2018 The Cleft Lip and Palate Association (CLAPA) is the only national charity supporting people and families affected by cleft lip and/or palate in the UK from diagnosis through to adulthood. Timetable • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • What’s today all about? • • • • Some ground rules and caveats • • • • • About the Adult Services Project • There are an estimated 75,000 people over the age of 16 living in the United Kingdom who were born with a cleft. • Understanding and supporting the unique needs and experiences of adults affected by cleft is very important to CLAPA. • From March 2018-February 2021, CLAPA is undertaking an exciting project looking at improving services for adults who were born with a cleft funded by the VTCT Foundation. • The goals are to research and understand the experiences, challenges and unmet needs of adults in the UK who were born with a cleft lip and/or palate. • The Adult Services Coordinator is the primary contact for this piece of work. What we did in Year One • • • • • So…what did we find at the roadshow? • We were humbled by how candidly people shared some of their most pivotal moments with us. • As you would expect, there were many different (oftentimes unique) experiences in the community, however there were some common themes that came up many times – these included: • The struggle of obtaining a successful referral to the cleft team as an adult • Being unsure what to expect at cleft team appointments • Not knowing (and health -

Oral Lichen Planus: a Case Report and Review of Literature

Journal of the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology Volume 10, Number 1 SPONSORS: ',/"!,0!4(/,/'9,!"/2!4/29s-%$)#)3 March 2008 34)%&%,,!"/2!4/2)%3s#/,,!'%.%8 www.aocd.org Journal of the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology 2007-2008 Officers President: Jay Gottlieb, DO President Elect: Donald Tillman, DO Journal of the First Vice President: Marc Epstein, DO Second Vice President: Leslie Kramer, DO Third Vice President: Bradley Glick, DO American Secretary-Treasurer: Jere Mammino, DO (2007-2010) Immediate Past President: Bill Way, DO Trustees: James Towry, DO (2006-2008) Osteopathic Mark Kuriata, DO (2007-2010) Karen Neubauer, DO (2006-2008) College of David Grice, DO (2007-2010) Dermatology Sponsors: Global Pathology Laboratory Stiefel Laboratories Editors +BZ4(PUUMJFC %0 '0$00 Medicis 4UBOMFZ&4LPQJU %0 '"0$% CollaGenex +BNFT2%FM3PTTP %0 '"0$% Editorial Review Board 3POBME.JMMFS %0 JAOCD &VHFOF$POUF %0 Founding Sponsor &WBOHFMPT1PVMPT .% A0$%t&*MMJOPJTt,JSLTWJMMF .0 4UFQIFO1VSDFMM %0 t'"9 %BSSFM3JHFM .% wwwBPDEPSg 3PCFSU4DIXBS[F %0 COPYRIGHT AND PERMISSION: written permission must "OESFX)BOMZ .% be obtained from the Journal of the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology for copying or reprinting text of .JDIBFM4DPUU %0 more than half page, tables or figurFT Permissions are $JOEZ)PGGNBO %0 normally granted contingent upon similar permission from $IBSMFT)VHIFT %0 the author(s), inclusion of acknowledgement of the original source, and a payment of per page, table or figure of #JMM8BZ %0 reproduced matFSJBMPermission fees -

Clinical Features of Benign Tumors of the External Auditory Canal According to Pathology

Central Annals of Otolaryngology and Rhinology Research Article *Corresponding author Jae-Jun Song, Department of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College of Clinical Features of Benign Medicine, 148 Gurodong-ro, Guro-gu, Seoul, 152-703, South Korea, Tel: 82-2-2626-3191; Fax: 82-2-868-0475; Tumors of the External Auditory Email: Submitted: 31 March 2017 Accepted: 20 April 2017 Canal According to Pathology Published: 21 April 2017 ISSN: 2379-948X Jeong-Rok Kim, HwibinIm, Sung Won Chae, and Jae-Jun Song* Copyright Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College © 2017 Song et al. of Medicine, South Korea OPEN ACCESS Abstract Keywords Background and Objectives: Benign tumors of the external auditory canal (EAC) • External auditory canal are rare among head and neck tumors. The aim of this study was to analyze the clinical • Benign tumor features of patients who underwent surgery for an EAC mass confirmed as a benign • Surgical excision lesion. • Recurrence • Infection Methods: This retrospective study involved 53 patients with external auditory tumors who received surgical treatment at Korea University, Guro Hospital. Medical records and evaluations over a 10-year period were examined for clinical characteristics and pathologic diagnoses. Results: The most common pathologic diagnoses were nevus (40%), osteoma (13%), and cholesteatoma (13%). Among the five pathologic subgroups based on the origin organ of the tumor, the most prevalent pathologic subgroup was the skin lesion (47%), followed by the epithelial lesion (26%), and the bony lesion (13%). No significant differences were found in recurrence rate, recurrence duration, sex, or affected side between pathologic diagnoses. -

CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal

Int. Adv. Otol. 2009; 5:(3) 401-403 CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal: A Case Report Sedat Ozturkcan, Ali Ekber, Riza Dundar, Filiz Gulustan, Demet Etit, Huseyin Katilmis Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery ‹zmir Atatürk Research and Training Hospital, Ministry of Health, ‹ZM‹R-TURKEY (SO, AE, FG, DE, HK) Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery Etimesgut Military Hospital , ANKARA-TURKEY (RD) Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in humans; however, its occurrence in the external auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon. The clinical manifestations of pigmented nevus of the EAC have been reported to include ear fullness, foreign body sensation, hearing impairment, and otalgia, but some cases were asymptomatic and were found incidentally. The treatment of choice for a symptomatic intradermal nevus in the EAC is complete excision. There has been no recurrence reported in the literature . A pedunculated, papillomatous hair-bearing lesion was detected in the external auditory canal of the patient who was on follow-up for pruritus. Clinical and pathologic features of an intradermal nevus of the external auditory canal are presented, and the literature reviewed. Submitted : 14 October 2008 Revised : 01 July 2009 Accepted : 09 July 2009 Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in left external auditory canal. Otomicroscopic humans; however, its occurrence in the external examination revealed a pedunculated, papillomatous auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon [1-4]. Intradermal hair-bearing lesion in the postero-inferior cartilaginous nevus is considered to be a form of benign cutaneous portion of the external auditory canal (Figure 1). -

4Th Annual Texas Children's Hospital Advanced Practice Provider

A Potpourri of Pediatric Dermatology 4th Annual Texas Children’s Hospital Advanced Practice Provider Conference April 2017 MOISE L. LEVY, M.D. DELL CHILDREN’S MEDICAL CENTER DELL MEDICAL SCHOOL/UT, AUSTIN AUSTIN, TX Conflicts of Interest Ø Anacor Ø Scioderm Ø Castle Creek Pharmaceuticals Ø Up to Date None Should Apply For This Presentation One way we are viewed… It’s just a birthmark 9 month old with asymptomatic scalp lesion noted in NICU; increases in size with straining But maybe something else… Sinus Pericranii Ø Communication between intra- and extracranial venous drainage pathways Ø Most are midline and non.pulsatile Ø Connect pericranial veins with superior sagittal sinus Ø TX depends on flow pattern/direction -Dominant; main flow via SP -Accessory; small flow via SP Neuroradiology 2007;49:505 Neurology 2009;72:e66 Case History 5 y/o girl w celiac disease Seen for evaluation of perianal growth Present, by hx, x 2 yrs No prior tx Case History Was seen by pediatric surgery Excised Condyloma - HPV 6, 16 Management? ARS – Pediatric Anogenital Warts When seeing a 5 yo with anogenital warts A. HPV testing should be done B. All cases are due to abuse C. All cases should be treated with imiquimod D. History and physical examination are key for suspicion of abuse E. Call Dr Eichenfield; he’ll know what to do Pediatric Anogenital Warts Age of onset and abuse - 6.5 ± 3.8 yrs (5.3 yrs) - 37% 2-12 yrs; 70% > 8 yrs - 4 yrs 8 months (83% female) HPV testing felt not of use… high subclinical History and PE key - physical findings abuse rare Arch Dermatol 1990;126:1575 Pediatrics 2005;116:815 Arch Dis Child 2006;91:696 Pediatr Dermatol 2006;23:199 J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013;26:e121 Age of Onset and Abuse Pediatr Dermatol 2006;23:199 ARS – Pediatric Anogenital Warts When seeing a 5 yo with anogenital warts A. -

Nevus Sebaceous

Nevus Sebaceous A nevus sebaceous (NEE vuhs sih BAY shus) is a type of birthmark that usually appears on the scalp. It may also appear on the face but this is less common. It is made of extra oil glands in the skin. It starts as a flat pink or orange plaque (slightly raised area). Hair does not grow in a nevus sebaceous. Typically, these are fairly small areas of skin. However, they can sometimes be larger and more noticeable. These birthmarks usually look the same until puberty. Hormonal changes cause them to become more raised. During adolescence (teen years) they can become very bumpy and wart-like. This can make them bothersome when brushing, combing or cutting the hair. A nevus sebaceous does not go away on its own. The cause is unknown. As a person gets older, typically after adolescence, abnormal changes to the area can sometimes occur. Your child’s doctor will monitor it over time. Diagnosis Your child’s doctor can usually diagnosis this kind of birthmark. If unsure, the doctor may take a small piece of the birthmark as a biopsy. The doctor will send it to a lab to be looked at under a microscope. This can confirm the diagnosis. Treatment Generally, it is very safe for your child’s doctor to simply watch a nevus sebaceous over time. This is especially true while your child is young (before puberty). A nevus sebaceous will not affect your child’s health, but you or your child may still want it to be taken off. If your child’s nevus sebaceous is large or becomes bothersome, it may be removed. -

Acral Compound Nevus SJ Yun S Korea

University of Pennsylvania, Founded by Ben Franklin in 1740 Disclosures Consultant for Myriad Genetics and for SciBase (might try to sell you a book, as well) Multidimensional Pathway Classification of Melanocytic Tumors WHO 4th Edition, 2018 Epidemiologic, Clinical, Histologic and Genomic Aspects of Melanoma David E. Elder, MB ChB, FRCPA University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA Napa, May, 2018 3rd Edition, 2006 Malignant Melanoma • A malignant tumor of melanocytes • Not all melanomas are the same – variation in: – Epidemiology – risk factors, populations – Cell/Site of origin – Precursors – Clinical morphology – Microscopic morphology – Simulants – Genomic abnormalities Incidence of Melanoma D.M. Parkin et al. CSD/Site-Related Classification • Bastian’s CSD/Site-Related Classification (Taxonomy) of Melanoma – “The guiding principles for distinguishing taxa are genetic alterations that arise early during progression; clinical or histologic features of the primary tumor; characteristics of the host, such as age of onset, ethnicity, and skin type; and the role of environmental factors such as UV radiation.” Bastian 2015 Epithelium associated Site High UV Low UV Glabrous Mucosa Benign Acquired Spitz nevus nevus Atypical Dysplastic Spitz Borderline nevus tumor High Desmopl. Low-CSD Spitzoid Acral Mucosal Malignant CSD melanoma melanoma melanoma melanoma melanoma 105 Point mutations 103 Structural Rearrangements 2018 WHO Classification of Melanoma • Integrates Epidemiologic, Genomic, Clinical and Histopathologic Features • Assists -

A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta)

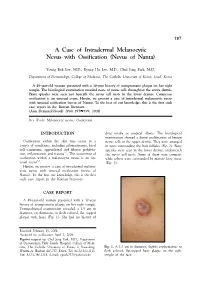

197 A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta) Young Bok Lee, M.D., Kyung Ho Lee, M.D., Chul Jong Park, M.D. Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea A 49-year-old woman presented with a 30-year history of asymptomatic plaque on her right temple. The histological examination revealed nests of nevus cells throughout the entire dermis. Bony spicules were seen just beneath the nevus cell nests in the lower dermis. Cutaneous ossification is an unusual event. Herein, we present a case of intradermal melanocytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. (Ann Dermatol (Seoul) 20(4) 197∼199, 2008) Key Words: Melanocytic nevus, Ossification INTRODUCTION drug intake or medical illness. The histological examination showed a dense proliferation of benign Ossification within the skin may occur in a nevus cells in the upper dermis. They were arranged variety of conditions, including pilomatricoma, basal in nests surrounding the hair follicles (Fig. 2). Bony cell carcinoma, appendageal and fibrous prolifera- spicules were seen in the lower dermis, underneath 1,2 tion, inflammation and trauma . The occurrence of the nevus cell nests. Some of them were compact ossification within a melanocytic nevus is an un- while others were surrounded by mature fatty tissue 3-5 usual event . (Fig. 3). Herein, we present a case of intradermal melano- cytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. -

Cutaneous Manifestations of Newborns in Omdurman Maternity Hospital

ﺑﺴﻢ اﷲ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﻦ اﻟﺮﺣﻴﻢ Cutaneous Manifestations of Newborns in Omdurman Maternity Hospital A thesis submitted in the partial fulfillment of the degree of clinical MD in pediatrics and child health University of Khartoum By DR. AMNA ABDEL KHALIG MOHAMED ATTAR MBBS University of Khartoum Supervisor PROF. SALAH AHMED IBRAHIM MD, FRCP, FRCPCH Department of Pediatrics and Child Health University of Khartoum University of Khartoum The Graduate College Medical and Health Studies Board 2008 Dedication I dedicate my study to the Department of Pediatrics University of Khartoum hoping to be a true addition to neonatal care practice in Sudan. i Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Salah Ahmed Ibrahim, Professor of Peadiatric and Child Health, who encouraged me throughout the study and provided me with advice and support. I am also grateful to Dr. Osman Suleiman Al-Khalifa, the Dermatologist for his support at the start of the study. Special thanks to the staff at Omdurman Maternity Hospital for their support. I am also grateful to all mothers and newborns without their participation and cooperation this study could not be possible. Love and appreciation to my family for their support, drive and kindness. ii Table of contents Dedication i Acknowledgement ii Table of contents iii English Abstract vii Arabic abstract ix List of abbreviations xi List of tables xiii List of figures xiv Chapter One: Introduction & Literature Review 1.1 The skin of NB 1 1.2 Traumatic lesions 5 1.3 Desquamation 8 1.4 Lanugo hair 9 1.5 -

Mongolian Spot

MONGOLIAN SPOT Authors: Roshan Bista, MBBS, Tribhuvan University, Institute of Medicine, Kathmandu, Nepal Prativa Pandey, MBBS, Tribhuvan University, Institute of Medicine, Kathmandu, Nepal Corresponding author: Roshan Bista, Fayetteville, North Carolina, USA E-mail: [email protected] PEER REVIEWED ARTICLE, VOL. 1, NR. 1, p. 12-18 PUBLISHED 27.11.2014 Abstract Colorful skin spots on a pediatric patient can easily be mistaken as signs of child abuse. Professionals should therefore gain knowledge about Mongolian spots; also known as Mongolian blue spots. These are flat, congenital and benign birthmarks, commonly located in sacro-coccygeal or lumbar area of an Photo: infant. Child abuse is a major public health problem https://www.flickr.com/photos/geowombats/1667757455 Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) across the world. The most common manifestations Figure 1: Plural Mongolian spots of physical child abuse are cutaneous, and their covering from the neck to the buttocks, recognition and differential diagnosis are of great both flanks and shoulders and even one of importance. Mongolian spots may appear as signs of the legs. child abuse; however, Mongolian spots are harmless. Keywords: Birthmark, Child abuse, Mongolian spot, Mongolian spots, Skin signs Introduction Mongolian spots (MS) refers to a macular blue-gray pigmentation usually on the sacral area of healthy Photo: Abby Lu infants. MS is usually present at birth or appears http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 via Wikimedia Commons within the first weeks of life. MS can be of various Figure 2: The central spot is more shapes and sizes, they may be single or multiple, they prominent and less likely to be mistaken as might vary from a few to more than 20 cm, and abuse, whereas the lateral spot is vaguer. -

Survey of Skin Disorders in Newborns: Clinical Observation in an Egyptian Medical Centre Nursery A.A

املجلة الصحية لرشق املتوسط املجلد الثامن عرش العدد اﻷول Survey of skin disorders in newborns: clinical observation in an Egyptian medical centre nursery A.A. El-Moneim 1 and R.E. El-Dawela 2 مسح لﻻضطرابات اجللدية لدى الولدان: مﻻحظة رسيرية يف حضانة يف مركز طبي يف مرص عبري أمحد عبد املنعم، رهيام عز الدولة الرشقاوي اخلﻻصة:مل َ ْت َظ اﻻضطرابات اجللدية لدى الولدان بدراسات جيدة يف مرص. وقد هدفت الباحثتان إىل دراسة أنامط التغريات اجللدية يف عينة من ِ الولدان املرصيني، وهي دراسة وصفية استباقية أترابية شملت ستة مئة وليد يف َّحضانة يف مستشفى جامعة سوهاج، َّوتضمنت الفحص اجللدي خﻻل اﻷيام اخلمسة اﻷوىل بعد الوﻻدة. وقد تم كشف اﻻضطرابات اجللدية لدى 240 ًوليدا )40%( ولوحظت الومحات لدى 100 وليد )%16.7(، ومعظمها من النمط ذي اخلﻻيا امليﻻنية )لطخات منغولية لدى 11.7% مع ومحات وﻻدية ذات ميﻻنية اخلﻻيا لدى 2.7%(. كام ُك ِش َف ْت العداوى الفطرية اجللدية، ومنها داء َّاملبيضات الفموية، وعدوى الفطريات يف مناطق احلفاظات أو َالـم َذح الناجم عن عدوى َّاملبيضات يف اﻷرفاغ )أصل الفخذ(، وذلك لدى 13.3%، ُوكشفت بعض العداوى اجلرثومية يف 1.3%من الولدان. وتشري املقارنات مع الدراسات اﻷخرى يف أرجاء العامل إىل معدل مرتفع للعدوى بالفطريات مع معدل منخفض للومحات الوﻻدية يف دراستنا للولدان، وتويص الباحثتان بإجراء تقييم روتيني جلدي للولدان، ّوﻻسيام يف ضوء املعدﻻت املرتفعة للعدوى اجللدية بالفطريات. ABSTRACT The frequency of neonatal skin disorders has not been well studied in Egypt. Our aim was to address patterns of dermatological changes in a sample of Egyptian newborns. In a descriptive prospective cohort study 600 newborns in Sohag University hospital nursery were dermatologically examined within the first 5 days of birth. -

The Birth-Mark Hawthorne, Nathaniel

The Birth-Mark Hawthorne, Nathaniel Published: 1843 Type(s): Short Fiction Source: http://gutenberg.org 1 About Hawthorne: Nathaniel Hawthorne was born on July 4, 1804, in Salem, Massachu- setts, where his birthplace is now a museum. William Hathorne, who emigrated from England in 1630, was the first of Hawthorne's ancestors to arrive in the colonies. After arriving, William persecuted Quakers. William's son John Hathorne was one of the judges who oversaw the Salem Witch Trials. (One theory is that having learned about this, the au- thor added the "w" to his surname in his early twenties, shortly after graduating from college.) Hawthorne's father, Nathaniel Hathorne, Sr., was a sea captain who died in 1808 of yellow fever, when Hawthorne was only four years old, in Raymond, Maine. Hawthorne attended Bowdoin College at the expense of an uncle from 1821 to 1824, befriending classmates Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and future president Franklin Pierce. While there he joined the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity. Until the publication of his Twice-Told Tales in 1837, Hawthorne wrote in the comparative obscurity of what he called his "owl's nest" in the family home. As he looked back on this period of his life, he wrote: "I have not lived, but only dreamed about living." And yet it was this period of brooding and writing that had formed, as Malcolm Cowley was to describe it, "the central fact in Hawthorne's career," his "term of apprenticeship" that would eventually result in the "richly med- itated fiction." Hawthorne was hired in 1839 as a weigher and gauger at the Boston Custom House.