Activism, Teaching, and Moral Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Problem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions Edward Matusek University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Matusek, Edward, "The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3733 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Problem of Evil in Augustine’s Confessions by Edward A. Matusek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Thomas Williams, Ph.D. Roger Ariew, Ph.D. Joanne Waugh, Ph.D. Charles B. Guignon, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 14, 2011 Keywords: theodicy, privation, metaphysical evil, Manichaeism, Neo-Platonism Copyright © 2011, Edward A. Matusek i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iii Chapter One: Introduction to Augustine’s Confessions and the Present Study 1 Purpose and Background of the Study 2 Literary and Historical Considerations of Confessions 4 Relevance of the Study for Various -

Gareth B. Matthews Curriculum Vitae1

1 Gareth B. Matthews curriculum vitae1 Born 8 July 1929; married; three children; six grandchildren. Died 17 April 2011; survived by wife, three children, and seven grandchildren. Education Franklin College (Indiana) 1947-51 A.B. (1951) Middlebury German School Summer 1950 Harvard University 1951-52 A.M. (1952) University of Tübingen Summer 1952 Free University of Berlin 1952-53 Harvard University 1957-60 Ph.D. (1961) Military Service United States Naval Reserve Active duty: 1954-57, served to rank of (full) Lieutenant Academic Appointments University of Virginia Assistant Professor 1960-61 University of Minnesota Assistant Professor 1961-65 Associate Professor 1965-69 University of Massachusetts Professor 1969-2005 Professor emeritus 2005-2011 Visiting Professorships Amherst College (1973, 1998, 2006, 2007) Brown University (1988, 2005) University of Calgary Summer School (1978, 1987) Harvard Summer School (1968, 1976) University of Minnesota (1981) Mount Holyoke College (1977, 1991, 2006) Smith College (1972, 1974, 1988, 2008) Tufts University (2008) Fellowships and Scholarships Harvard University Graduate School Scholarship (1951-52) George Santayana Postdoctoral Fellowship (1967-68) Rotary Foundation Fellowship (1952-53) National Endowment for the Humanities Research Fellowships (1982-83; 1989-90) Institute for Advanced Study Member (January – June, 1986 for project: Augustine and Descartes: philosophy from a first-person perspective) Presentations A. To the American Philosophical Association 2 Eastern Division: 1965, 1970, 1972, 1974, 1976, 1980, 1984, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2005 Central Division: 1962, 1965, 1967, 1970, 1972, 1973, 1980, 1982, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2002 Pacific Division: 1974, 1979, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1992, 1994, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2003, 2004 B. -

Proposal for an APA Grant to Support the Development of “What's the Big

Grant Proposal “What’s the Big Idea?” Page 1 Proposal for an APA Grant to support the Development of “What’s the Big Idea?” Thomas E. Wartenberg, Project Director ABSTRACT What’s the Big Idea? is a website that will be based on approximately 90-minutes of film and a comprehensive curriculum introducing ethics to middle school children through feature film segments that are introduced and discussed by philosophers. The website will be composed of five chapters: on bullying, lying, peer pressure, friendship, and environmental ethics. Each chapter will feature video clips from popular films, clips of philosophers introducing the issue, and support materials facilitating discussion in the classroom. The materials will guide a variety of activities before, during, and after the presentation of the film clips. We have nearly finished a rough version of Chapter 1 on “Bullying ” and are requesting $10,000 from The American Philosophical Association to produce the second and third 15-minute sections on the topics of “Lying” and “Friendship” and to develop the accompanying curriculum. The ethical issues of bullying, peer pressure, friendship, lying and environmental action were selected by middle school students in three different schools as the most relevant ethical issues in their lives. Grant Proposal “What’s the Big Idea?” Page 2 1. Purpose of the Project Although the teaching of philosophy in pre-college classrooms has been expanding lately, most programs for doing so have focused on either high school or elementary school classrooms. What’s the Big Idea? will provide middle school teachers with all the materials necessary for having classrooms discussions of five important ethical issues: bullying, lying, peer pressure, friendship, and environmental ethics. -

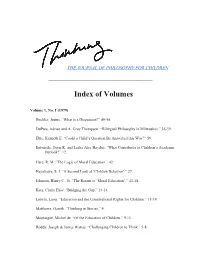

Index of Thinking Volumes

THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY FOR CHILDREN __________________________________________________ Index of Volumes Volume 1, No. 1 (1979) Buchler, Justus. “What is a Discussion?” 4954. DuPuis, Adrian and A. Gray Thompson. “Bilingual Philosophy in Milwaukee.” 3539. Eble, Kenneth E. “Could a Child’s Question Be Answered this Way?” 59. Entwistle, Doris R. and Leslie Alec Hayduc. “What Contributes to Children’s Academic Outlook?” 12. Hare, R. M. “The Logic of Moral Education.” 42. Hayakawa, S. I. “A Second Look at ‘Childish Behavior’.” 27. Johnson, Henry C., Jr. “The Return to ‘Moral Education’.” 4148. Katz, Claire Elise. “Bridging the Gap,” 1314. Letwin, Leon. “Education and the Constitutional Rights for Children.” 1119. Matthews, Gareth. “Thinking in Stories.” 4. Montaigne, Michel de. “Of the Education of Children.” 911. Roddy, Joseph & James Watras. “Challenging Children to Think.” 58. Simon, Charlann. “Philosophy for Students with Learning Disabilities.” 2133. Wagner, Paul A.“Philosophy, Children, and ‘Doing Science’.” 5557. Worsfold, Victor L. “What Claims Can Children Make?” 13. Volume 1, No. 2 (1979) Aman, Kenneth and Sister Anna Maria Hartman. “Philosophy for Children in a SpanishSpeaking Contest.” 410. Barr, Donald. “How Important are Categories for Children.” 11. Berman, Ronald. “On Writing Good.” 12. Brent, Frances. “Philosophy and the MiddleSchool Student.” 39. Chesternon, Gilbert Keith. “The Ethics of Elfland.” 1320. Dostoevsky, Fedor. “Ghost and Eternity.” 27. Education Commission of the States. “The Higher Level Skills: Tomorrow’s ‘Basics’.” 11. Freire, Paulo. “Education Through Dialogue.” 11. Gosse, Edmund. “Untitled from Father and Son.” 4346. Hullfish, H. Gordon. “Thinking and Meaning.” 12. -

Intentional Disruption Expanding Access to Philosophy

Intentional Disruption Expanding Access to Philosophy Edited by Stephen Kekoa Miller Oakwood Friends School; Marist College Series in Philosophy Copyright © 2021 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Philosophy Library of Congress Control Number: 2021938620 ISBN: 978-1-64889-191-5 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press using elements designed by Timothy Dykes, unsplash.com. Table of contents Foreword v Wendy C. Turgeon St. Joseph’s College Chapter 1 What to Consider when Considering a Pre-college Philosophy Program: Frequently Asked Questions from Those considering -

Philosophy 501/CCT 603 Foundations of Philosophical Thought Arthur

Philosophy 501/CCT 603 Foundations of Philosophical Thought Arthur Millman Fall 2018 Office: W/5/020 Wednesdays 7:00 Phone: (617) 287-6538 Room: W/4/170 E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: W 5-7, Th 7-8 and by arrangement at other times (face-toface or online) This course introduces graduate students in the Critical and Creative Thinking Graduate Program and other graduate programs to some of the traditional problems and methods of philosophical inquiry. It also relates philosophy to concerns about good thinking, educational reform, and teaching for effective thinking and considers how to infuse philosophical thinking into workplaces, school curricula, other academic disciplines, and our own lives. We will become acquainted with several central philosophical problems. What is it to think philosophically? Why should one be moral? What is justice? What is knowledge? How can concrete moral issues such as abortion, human embryo research, and war be thought through? We will not find final answers to these questions. Rather we will: (1) seek to understand why these are such important and open questions, (2) begin to explore ways of answering them, (3) consider how to draw students and others into further engagement with philosophical thinking, and (4) find connections between such questions and other questions we have. The course provides a basis for further work in CCT, Education or many other fields. The course will proceed primarily through discussion and writing in a (virtual) classroom community of inquiry. You are expected to contribute to the learning experience of the class as well as to gain useful insights from others. -

Curriculum Vitae

THOMAS ALLEN BLACKSON Curriculum Vitae Philosophy Faculty School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies Arizona State University 975 S. Myrtle Ave P.O. Box 87432 Tempe, AZ 85287-4302. USA Email: [email protected] Academic website: tomblackson.com EDUCATION Ph.D., Philosophy. University of Massachusetts, 1988 B.A. De Pauw University, 1980 (CITI) Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative: - Humanities Responsible Conduct of Research (9/28/11) - Group 2 Social & Behavioral Research Investigators and Key Personnel (11/9/11) EMPLOYMENT Associate Professor of Philosophy, Arizona State University, 1997- Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Arizona State University, 1995-1997 Associate Professor of Philosophy, Temple University, 1995 Visiting Lecturer in Philosophy, University of Pennsylvania, Spring 1995 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Temple University, 1992-1995 Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Arizona State University, 1990-1992 Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy, North Carolina State University, 1988-1990 Visiting Instructor in Philosophy, North Carolina State University, 1987-1988 NEH Summer Seminar Assistant to Gary Matthews, Philosophy of Children, 1986 Systems Analyst, MIT (Sloan School of Management), 1982-1983. Programmer, Instrumentation Laboratories (Route #128, Boston), 1980-1982. SPECIALIZATION: History of Ancient Philosophy COMPETENCE: Ethics, Epistemology, History of Modern Philosophy, History of Analytic Philosophy, Logic, Metaphysics, Philosophy of Language, Philosophy of Mathematics, Philosophy of Mind LANGUAGES: Greek, Latin CV, Blackson, 2019, 2 PUBLICATIONS Books (peer reviewed) B2 Ancient Greek Philosophy. From the Presocratics through the Hellenistic Philosophers. (Wiley-Blackwell: United Kingdom, 2011; 271 + xv.) Reviewed in The Classical Review, 62, 2 (2012), 394-396. “B.’s book is an admirably clear introductory-level overview of philosophy from the Presocratics through to the Hellenistic period. -

Kooky Objects Revisited: Aristotle's Ontology

r 2008 The Author Journal compilation r 2008 Metaphilosophy LLC and Blackwell Publishing Ltd Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK, and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA METAPHILOSOPHY Vol. 39, No. 1, January 2008 0026-1068 KOOKY OBJECTS REVISITED: ARISTOTLE’S ONTOLOGY S. MARC COHEN Abstract: This is an investigation of Aristotle’s conception of accidental com- pounds (or ‘‘kooky objects,’’ as Gareth Matthews has called them)Fentities such as the pale man and the musical man. I begin with Matthews’s pioneering work into kooky objects, and argue that they are not so far removed from our ordinary thinking as is commonly supposed. I go on to assess their utility in solving some familiar puzzles involving substitutivity in epistemic contexts, and compare the kooky object approach to more modern approaches involving the notion of referential opacity. I conclude by proposing that Aristotle provides an implicit role for kooky objects in such metaphysical contexts as the Categories and Metaphysics. Keywords: accident, Aristotle, ontology, sameness, substitution. In the course of my forty-year friendship and collaboration with Gary Matthews, he has taught me many things, more than I have space to enumerate here. So I won’t try to enumerate them. Instead, I am going to focus on just one of those thingsFthe idea that it is worth taking seriously a certain aspect of Aristotle’s ontology that seems at least quaint, if not weird, to our contemporary ears. Its quaintness, or weirdness, consists in the fact that it is a finer-grained ontology than we are accustomed toFit distinguishes between entities that we tend not to distinguish, and hence gives ontological status to entities that philoso- phers nowadays are not entirely comfortable with. -

Is There Theology in This Book?

Journal Code Article ID Dispatch: 14.08.17 CE: Bais, Irish Jill R I R T 1 3 0 3 6 No. of Pages: 10 ME: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 REVIEW ARTICLE 8 9 10 11 Is there Theology in this Book? 12 13 Jonathan Teubner Q1 14 15 The Theology of Augustine’s Confessions, Paul Rigby, Cambridge University 16 Press, 2015 (ISBN 978-1107094925), xv + 340 pp., hb £67 17 Augustine’s Confessions: Philosophy in Autobiography, William E. Mann (ed.), 18 Oxford University Press, 2014 (ISBN 978-0199577552), xi +223 pp., hb £36 19 The Space of Time: A Sensualist Interpretation of Time in Augustine, 20 Confessions X to XII, David van Dusen, Brill, 2014 (ISBN 978-9004266865), xv + 21 358 pp., hb €149 22 23 Confessions: Books 1–8, Augustine of Hippo, trans. Carolyn J.-B. Hammond, Harvard University Press, 2014 (ISBN 978-0674996854), lxv + 413 pp., hb $26 24 25 Confessions: Books 9–13, Augustine of Hippo, trans. Carolyn J.-B. Hammond, 26 Harvard University Press, 2016, (ISBN 978-0674996939), xlii + 446 pp., hb $26 27 Confessions, Augustine of Hippo, trans. Sarah Ruden, The Modern Library, 2017 28 (ISBN 978-0812996562), xli + 484 pp., $28 29 30 31 Abstract 32 This review essay discusses three recent books on, and two new translations of, 33 Augustine’s Confessions. Long appreciated for its stylistic beauty and existential profun- 34 dity, the Confessions has recently become a resource for creative philosophical reflection in 35 both the analytic and continental traditions. However, there has not been a recent theolog- 36 ical treatment of the Confessions, a curious lacuna considering Augustine’s importance for 37 the history of Christian doctrine. -

Semantic Properties and the Computational Model of Mind

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1990 Semantic properties and the computational model of mind. Randall K. Campbell University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Campbell, Randall K., "Semantic properties and the computational model of mind." (1990). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2062. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2062 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UMASS/AMHERST 312Qt,bQ13S7t.lDS S) (j DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AT AMHERST LD 3234 M267 1990 C1895 SEMANTIC PROPERTIES AND THE COMPUTATIONAL MODEL OF MIND A Dissertation Presented by RANDALL K, CAMPBELL Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 1990 Department of Philosophy Copyright by (7) Randall K. Campbell 1990 All Rights Reserved SEMANTIC PROPERTIES AND THE COMPUTATIONAL MODEL OF MIND A Dissertation Presented by RANDALL K. CAMPBELL Approved as to style and content by: Gareth Matthews, Chair Bruce Aune, Member Fred Feldman, Member Neil Stillings, Member! ABSTRACT -

The University of Oklahoma Norman, Oklahoma 73019-2006 (405) 325-6324 Number 5 Fall 1998

OU PHILOSOPHY NEWSLETTER A Newsletter Published by the Department of Philosophy The University of Oklahoma Norman, Oklahoma 73019-2006 (405) 325-6324 Number 5 Fall 1998 GREETINGS FROM THE CHAIR Once again, it is my pleasure to greet you following another exciting and eventful academic year. Perhaps the most important of our activities was the national search to fill the Kingfisher Chair in Philosophy of Religion and Ethics, following Tom Boyd's retirement after the spring 1997 semester. (By the way, from all reports and not unexpectedly, Tom and Barbara are flourishing in the mountains of Colorado.) The applicant response to our opening was overwhelming, and the three finalists for the position were superb. I am thrilled to announce that Professor Linda Zagzebski, chair of the Department of Philosophy at Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, will be joining our department in the fall of 1999 as the third tenant of the Kingfisher Chair. I should add, with some pride, that Linda is the first woman to hold an endowed chair in the history of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Oklahoma. Congratulations and welcome, Professor Zagzebski! Other notable events during the academic year 1997-98 include an active colloquium series featuring invited lecturers from other schools (Professors Robert Batterman, of Ohio State University, and Lynne Rudder Baker, of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, among others) and our brownbag series. During the year, our newly established Undergraduate Advisory Council sponsored a couple of interdisciplinary brownbag discussions that brought together majors from the Philosophy, Computer Science, and Psychology departments. -

1999 Board of Directors Beauty, Negativity, and Autonomy

WWNESDAY, OCTOBER 27 Ie·IN TIlE F RANKLIN ROOM Registration: 5:30 - 10:00 P.M. Washington Plaza Hotel Lobby THE WORK OF ART: STYLE AND IDENTITY Chair: Richard Shusterman Philosophy, Temple University Please Note: All room assignments subject to change. Speakers: Dale Jacquene Philosophy, Pennsylv:mia State University, 9:00 - 11:00 A.M. Budget Committee Meeting-Hotel Board Room ~Goodman on the Concept of Style" Julie C. Van CamP'\. 1:00 - 5:30 P.M. Trustees Meeting-Hotel Board Room Philosophy, California State University· Long Beach, "A Pragmatic Approach 6:00 - 8:00 P.M. Trustees Dinner-Diplomats Room to the Identity of Works of Art" Commentator: John Dilworth 8:00 - 11:00 P.M. Opening Reception-Hotel Lounge Philosophy, Western Michigan University BOOK DISPLAy·LINCOLN ROOM 8:30 A.M. - 4:30 P.M. THURSDAY·FRIDAY 8,}0 A.M. - },OO P.M. SATURDAY Thursday, October 28 Session II . 11:10A.M. -l:00P.M_ THURSDAY, OCTOBER 28 ITa·1N TIlE FRANKLIN R OOM Registration: 8:30 A.M. - 4:30 P.M. Washington Plaza Hotel Lobby SESSION I - 9:00 · 10:50 A.M. THE AESTHETICS OF PLACE: THE SHAPING OF EXPERIENCE, MEANING, AND VALUES la-IN TIlE ADAMS ROOM Chair: Anthony J. Cascardi Hwnanities, University of California.Berkeley, THINKING THROUGH CINEMA: "Recent Directions in the Aesthetics of SpaceD THE PERFORMANCE OF NEW SELYES Speakers: Dean MacCannell Chair: Angela Curran Environmental Design and Landscape Philosophy, Mt. Holyoke College Architecture, University of California-Davis Speakers: Cynthia Fredand Pauline von Bonsdorff Philosophy, University of Houston,