Kooky Objects Revisited: Aristotle's Ontology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Problem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions Edward Matusek University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Matusek, Edward, "The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3733 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Problem of Evil in Augustine’s Confessions by Edward A. Matusek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Thomas Williams, Ph.D. Roger Ariew, Ph.D. Joanne Waugh, Ph.D. Charles B. Guignon, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 14, 2011 Keywords: theodicy, privation, metaphysical evil, Manichaeism, Neo-Platonism Copyright © 2011, Edward A. Matusek i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iii Chapter One: Introduction to Augustine’s Confessions and the Present Study 1 Purpose and Background of the Study 2 Literary and Historical Considerations of Confessions 4 Relevance of the Study for Various -

The Unity of Heidegger's Project

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree fV\o Year Too£ Name of Author A-A COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D. -

Being Qua Being

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN part iv BEING AND BEINGS 114_Shields_Ch14.indd4_Shields_Ch14.indd 334141 11/6/2012/6/2012 66:02:56:02:56 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN 114_Shields_Ch14.indd4_Shields_Ch14.indd 334242 11/6/2012/6/2012 66:02:59:02:59 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN Chapter 14 BEING QUA BEING Christopher Shields I. Three Problems about the Science of Being qua Being ‘There is a science (epistêmê),’ says Aristotle, ‘which studies being qua being (to on hê(i) on), and the attributes belonging to it in its own right’ (Met. 1003a21–22). This claim, which opens Metaphysics IV 1, is both surprising and unsettling—sur- prising because Aristotle seems elsewhere to deny the existence of any such science and unsettling because his denial seems very plausibly grounded. He claims that each science (epistêmê) studies a unified genus (APo 87a39-b1), but he denies that there is a single genus for all beings (APo 92b14; Top. 121a16, b7–9; cf. Met. 998b22). Evidently, his two claims conspire against the science he announces: if there is no genus of being and every science requires its own genus, then there is no science of being. This seems, moreover, to be precisely the conclusion drawn by Aristotle in his Eudemian Ethics, where he maintains that we should no more look for a gen- eral science of being than we should look for a general science of goodness: ‘Just as being is not something single for the things mentioned [viz. -

Vol. 3 No. 1 January – June, 2014 Page the QUESTION of “BEING”

Vol. 3 No. 1 January – June, 2014 THE QUESTION OF “BEING” IN AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY Lucky U. OGBONNAYA, M.A. Essien Ukpabio Presbyterian Theological College, Itu, Nigeria Abstract This work is of the view that the question of being is not only a problem in Western philosophy but also in African philosophy. It, therefore, posits that being is that which is and has both abstract and concrete aspect. The work arrives at this conclusion by critically analyzing and evaluating the views of some key African philosophers with respect to being. With this, it discovers that the way that these African philosophers have postulated the idea of being is in the same manner like their Western philosophers whom they tried to criticize. This work tries to synthesize the notions of beings of these African philosophers in order to reach at a better understanding of being. This notion of being leans heavily on Asouzu’s ibuanyidanda ontology which does not bifurcate or polarize being, but harmonizes entities or realities that seem to be contrary or opposing in being. KEYWORDS: Being, Ifedi, Ihedi, Force (Vital Force), Missing Link, Muntu, Ntu, Nkedi, Ubuntu, Uwa Introduction African philosophy is a critical and rational explanation of being in African context, and based on African logic. It is in line with this that Jonathan Chimakonam avers that “in African philosophy we study reality of which being is at the center” (2013, 73). William Wallace remarks that “being signifies a concept that has the widest extension and the least comprehension” (1977, 86). It has posed a lot of problems to philosophers who tend to probe into it, its nature and manifestations. -

Philosophy of Language

Philosophy OF Language Julian J. Schlöder, University OF AmsterDAM YEREVAN Academy FOR Linguistics AND Philosophy 2019 1 = 99 William Lycan, (Routledge, 3rD ed, 2019). ◦ Philosophy OF Language ◦ Stephen Yablo, LecturE NOTES ON Philosophy OF Language. > https: //ocw.mit.edu/courses/linguistics-and-philosophy/ 24-251-introduction-to-philosophy-of-language-fall-2011/ lecture-notes/ Jeff Speaks, (StanforD Encyclopedia OF ◦ Theories OF Meaning Philosophy). > https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/meaning 2 = 99 Language IS . ◦ REMARKABLE 3 = 99 ArE Pringles POTATO chips? 4 = 99 ◦ The British COURTS SPEND SOME TWO YEARS ON THAT question. > At STAKE WAS SOME £100 MILLION IN TAXes. Yes! A Pringle IS “MADE FROM POTATO ◦ The VAT AND Duties Tribunal: flOUR IN THE SENSE THAT ONE CANNOT SAY THAT IT IS NOT MADE FROM POTATO flour.” No! Pringles CONTAIN “A NUMBER OF ◦ The High Court OF Justice: SIGNIfiCANT INGREDIENTS” AND “CANNOT BE SAID TO BE ‘MADE OF’ ONE OF them.” TheY DO NOT EXHIBIT “POTATONESS”. (TheY ARE MORE LIKE BREAD THAN LIKE chips.) : Yes! The TEST FOR “POTATONESS” IS AN ◦ The Court OF Appeal “Aristotelian QUESTION” ABOUT “ESSENCE” AND THE COURT HAS “NO REAL IDEA” OF WHAT THAT means. Rather, THE QUESTION “WOULD PROBABLY BE ANSWERED IN A MORE RELEVANT AND SENSIBLE WAY BY A CHILD CONSUMER THAN BY A FOOD SCIENTIST OR A CULINARY pendant.” 5 = 99 THE QUESTIONS ◦ Fact: WORDS AND SENTENCES HAVE MEANINGSOR ARE MEANINGFUL. ◦ Fact: NOT ALL SEQUENCES OF sounds/letters ARE meaningful. ◦ But WHAT ARE meanings? Alternatively: WHAT IS meaningfulness? ◦ HoW DO LINGUISTIC ITEMS RELATE TO meanings? (And WHY DO SOME ITEMS FAIL TO RELATE TO meanings?) ◦ IN WHAT RELATIONS DO humans, LANGUAGES AND MEANINGS stand? 6 = 99 MEANING FACTS HerE ARE SOME THINGS THAT WE KNOW ABOUT meanings, WHATEVER THEY ARe. -

CURRICULUM VITAE KATALIN BALOG Department of Philosophy University-Newark 175 University Ave., Newark, NJ 07102 Rutgers Home

CURRICULUM VITAE KATALIN BALOG Department of Philosophy University-Newark 175 University Ave., Newark, NJ 07102 Rutgers Home page: http://hypatiaonhudson.net/ Email: [email protected] Education and work history 2018- present – professor, Rutgers University – Newark. 2010- 2018 – associate professor, Rutgers University – Newark. 2006- 2010 – associate professor, Yale University. 2000-2006 – assistant professor, Yale University. 1998-1999 – Mellon postdoctoral fellow, Cornell University. 1998 – Ph.D. Philosophy, Rutgers University. Ph.D. Thesis Director: Brian Loar Conceivability and Consciousness* Degree obtained: October 1998 *My dissertation was selected by Robert Nozick for publication in the series Harvard Dissertations in Philosophy. Areas of specialization Philosophy of mind Philosophy of psychology/cognitive science Free will and personal identity Metaphysics Value theory Buddhist philosophy Publications Forthcoming: 1. Either/Or: Subjectivity, Objectivity and Value (pdf). In: Transformative Experience: New Philosophical Essays, eds. Enoch Lambert and John Schwenkler, Oxford University Press (UK), 2020. 2. Disillusioned (pdf). Journal of Consciousness Studies 27 (1-2), 2020. Published: 3. Hard, Harder, Hardest (pdf), in Sensations, Thoughts, Langugage: Essays in Honor of Brian Loar (pp. 265-289), Arthur Sullivan (ed.), Routledge Festschrifts in Philosophy, Routledge, 2020. 4. Consciousness and Meaning; Selected Essays by Brian Loar, Oxford University Press, 2017. (Editor, Introduction to Loar’s Philosophy of Mind, pp. 137-152) pdf. 5. Illusionism’s Discontent (pdf). Journal of Consciousness Studies, 23(11-12), 40-51, 2016. 6. Acquaintance and the Mind-Body Problem (pdf).In Christopher Hill and Simone Gozzano (Eds.), New Perspectives on Type Identity: The Mental and the Physical (pp. 16-43). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. 7. In Defense of the Phenomenal Concept Strategy (pdf). -

APA Eastern Division 2019 Annual Meeting Program

The American Philosophical Association EASTERN DIVISION ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM SHERATON NEW YORK TIMES SQUARE NEW YORK, NEW YORK JANUARY 7 – 10, 2019 Visit our table at APA Eastern OFFERING A 20% (PB) / 40% (HC) DISCOUNT WITH FREE SHIPPING TO THE CONTIGUOUS U.S. FOR ORDERS PLACED AT THE CONFERENCE. THE POETRY OF APPROACHING HEGEL’S LOGIC, GEORGES BATAILLE OBLIQUELY Georges Bataille Melville, Molière, Beckett Translated and with an Introduction by Angelica Nuzzo Stuart Kendall THE POLITICS OF PARADIGMS ZHUANGZI AND THE Thomas S. Kuhn, James B. Conant, BECOMING OF NOTHINGNESS and the Cold War “Struggle for David Chai Men’s Minds” George A. Reisch ANOTHER AVAILABLE APRIL 2019 WHITE MAN’S BURDEN Josiah Royce’s Quest for a Philosophy THE REAL METAPHYSICAL CLUB of white Racial Empire The Philosophers, Their Debates, and Tommy J. Curry Selected Writings from 1870 to 1885 Frank X. Ryan, Brian E. Butler, and BOUNDARY LINES James A. Good, editors Philosophy and Postcolonialism Introduction by John R. Shook Emanuela Fornari AVAILABLE MARCH 2019 Translated by Iain Halliday Foreword by Étienne Balibar PRAGMATISM APPLIED William James and the Challenges THE CUDGEL AND THE CARESS of Contemporary Life Reflections on Cruelty and Tenderness Clifford S. Stagoll and David Farrell Krell Michael P. Levine, editors AVAILABLE MARCH 2019 AVAILABLE APRIL 2019 LOVE AND VIOLENCE BUDDHIST FEMINISMS The Vexatious Factors of Civilization AND FEMININITIES Lea Melandri Karma Lekshe Tsomo, editor Translated by Antonio Calcagno www.sunypress.edu II IMPORTANT NOTICES FOR MEETING ATTENDEES SESSION LOCATIONS Please note: this online version of the program does not include session locations. -

Gareth B. Matthews Curriculum Vitae1

1 Gareth B. Matthews curriculum vitae1 Born 8 July 1929; married; three children; six grandchildren. Died 17 April 2011; survived by wife, three children, and seven grandchildren. Education Franklin College (Indiana) 1947-51 A.B. (1951) Middlebury German School Summer 1950 Harvard University 1951-52 A.M. (1952) University of Tübingen Summer 1952 Free University of Berlin 1952-53 Harvard University 1957-60 Ph.D. (1961) Military Service United States Naval Reserve Active duty: 1954-57, served to rank of (full) Lieutenant Academic Appointments University of Virginia Assistant Professor 1960-61 University of Minnesota Assistant Professor 1961-65 Associate Professor 1965-69 University of Massachusetts Professor 1969-2005 Professor emeritus 2005-2011 Visiting Professorships Amherst College (1973, 1998, 2006, 2007) Brown University (1988, 2005) University of Calgary Summer School (1978, 1987) Harvard Summer School (1968, 1976) University of Minnesota (1981) Mount Holyoke College (1977, 1991, 2006) Smith College (1972, 1974, 1988, 2008) Tufts University (2008) Fellowships and Scholarships Harvard University Graduate School Scholarship (1951-52) George Santayana Postdoctoral Fellowship (1967-68) Rotary Foundation Fellowship (1952-53) National Endowment for the Humanities Research Fellowships (1982-83; 1989-90) Institute for Advanced Study Member (January – June, 1986 for project: Augustine and Descartes: philosophy from a first-person perspective) Presentations A. To the American Philosophical Association 2 Eastern Division: 1965, 1970, 1972, 1974, 1976, 1980, 1984, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2005 Central Division: 1962, 1965, 1967, 1970, 1972, 1973, 1980, 1982, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2002 Pacific Division: 1974, 1979, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1992, 1994, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2003, 2004 B. -

The Philosophical Development of Gilbert Ryle

THE PHILOSOPHICAL DEVELOPMENT OF GILBERT RYLE A Study of His Published and Unpublished Writings © Charlotte Vrijen 2007 Illustrations front cover: 1) Ryle’s annotations to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus 2) Notes (miscellaneous) from ‘the red box’, Linacre College Library Illustration back cover: Rodin’s Le Penseur RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN The Philosophical Development of Gilbert Ryle A Study of His Published and Unpublished Writings Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Wijsbegeerte aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. F. Zwarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 14 juni 2007 om 16.15 uur door Charlotte Vrijen geboren op 11 maart 1978 te Rolde Promotor: Prof. Dr. L.W. Nauta Copromotor: Prof. Dr. M.R.M. ter Hark Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. Dr. D.H.K. Pätzold Prof. Dr. B.F. McGuinness Prof. Dr. J.M. Connelly ISBN: 978-90-367-3049-5 Preface I am indebted to many people for being able to finish this dissertation. First of all I would like to thank my supervisor and promotor Lodi Nauta for his comments on an enormous variety of drafts and for the many stimulating discussions we had throughout the project. He did not limit himself to deeply theoretical discussions but also saved me from grammatical and stylish sloppiness. (He would, for example, have suggested to leave out the ‘enormous’ and ‘many’ above, as well as by far most of the ‘very’’s and ‘greatly’’s in the sentences to come.) After I had already started my new job outside the academic world, Lodi regularly – but always in a pleasant way – reminded me of this other job that still had to be finished. -

Proposal for an APA Grant to Support the Development of “What's the Big

Grant Proposal “What’s the Big Idea?” Page 1 Proposal for an APA Grant to support the Development of “What’s the Big Idea?” Thomas E. Wartenberg, Project Director ABSTRACT What’s the Big Idea? is a website that will be based on approximately 90-minutes of film and a comprehensive curriculum introducing ethics to middle school children through feature film segments that are introduced and discussed by philosophers. The website will be composed of five chapters: on bullying, lying, peer pressure, friendship, and environmental ethics. Each chapter will feature video clips from popular films, clips of philosophers introducing the issue, and support materials facilitating discussion in the classroom. The materials will guide a variety of activities before, during, and after the presentation of the film clips. We have nearly finished a rough version of Chapter 1 on “Bullying ” and are requesting $10,000 from The American Philosophical Association to produce the second and third 15-minute sections on the topics of “Lying” and “Friendship” and to develop the accompanying curriculum. The ethical issues of bullying, peer pressure, friendship, lying and environmental action were selected by middle school students in three different schools as the most relevant ethical issues in their lives. Grant Proposal “What’s the Big Idea?” Page 2 1. Purpose of the Project Although the teaching of philosophy in pre-college classrooms has been expanding lately, most programs for doing so have focused on either high school or elementary school classrooms. What’s the Big Idea? will provide middle school teachers with all the materials necessary for having classrooms discussions of five important ethical issues: bullying, lying, peer pressure, friendship, and environmental ethics. -

Ontological Pluralism About Non-Being Sara Bernstein, University of Notre Dame

Ontological Pluralism about Non-Being Sara Bernstein, University of Notre Dame Forthcoming in Non-Being: New Essays on the Metaphysics of Nonexistence, eds. Bernstein and Goldschmidt, Oxford University Press (UK) Neither square circles nor manned lunar stations exist. But might they fail to exist in different ways? A common assumption is “no”: everything that fails to exist, fails to exist in exactly the same way. Non-being doesn’t have joints or structure, the thinking goes—it is just a vast, undifferentiated nothingness. Even proponents of ontological pluralism, the view that there are multiple ways of being, do not entertain the possibility of multiple ways of non-being. This paper is dedicated to the latter idea. I argue that ontological pluralism about non-being, roughly, the view that there are multiple ways of non-being, is both more plausible and defensible and than it first seems, and it has many useful applications across a wide variety of metaphysical and explanatory problems.1 Here is the plan. In section 1, I lay out ontological pluralism about non-being in detail, drawing on principles of ontological pluralism about being. I address whether and how the two pluralisms interact: some pluralists about non-being are monists about being, and vice-versa. I discuss logical quantification strategies for pluralists about non-being. In Section 2, I examine precedent for pluralism about non-being in the history of philosophy. In section 3, I discuss several applications of pluralism about non-being. I suggest that the view has explanatory power across a variety of domains, and that the the view can account for differences between nonexistent past and future times, between omissions and absences, and between different kinds of fictional objects. -

Index of Thinking Volumes

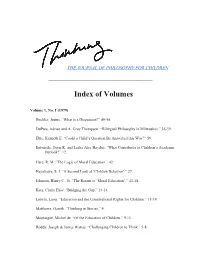

THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY FOR CHILDREN __________________________________________________ Index of Volumes Volume 1, No. 1 (1979) Buchler, Justus. “What is a Discussion?” 4954. DuPuis, Adrian and A. Gray Thompson. “Bilingual Philosophy in Milwaukee.” 3539. Eble, Kenneth E. “Could a Child’s Question Be Answered this Way?” 59. Entwistle, Doris R. and Leslie Alec Hayduc. “What Contributes to Children’s Academic Outlook?” 12. Hare, R. M. “The Logic of Moral Education.” 42. Hayakawa, S. I. “A Second Look at ‘Childish Behavior’.” 27. Johnson, Henry C., Jr. “The Return to ‘Moral Education’.” 4148. Katz, Claire Elise. “Bridging the Gap,” 1314. Letwin, Leon. “Education and the Constitutional Rights for Children.” 1119. Matthews, Gareth. “Thinking in Stories.” 4. Montaigne, Michel de. “Of the Education of Children.” 911. Roddy, Joseph & James Watras. “Challenging Children to Think.” 58. Simon, Charlann. “Philosophy for Students with Learning Disabilities.” 2133. Wagner, Paul A.“Philosophy, Children, and ‘Doing Science’.” 5557. Worsfold, Victor L. “What Claims Can Children Make?” 13. Volume 1, No. 2 (1979) Aman, Kenneth and Sister Anna Maria Hartman. “Philosophy for Children in a SpanishSpeaking Contest.” 410. Barr, Donald. “How Important are Categories for Children.” 11. Berman, Ronald. “On Writing Good.” 12. Brent, Frances. “Philosophy and the MiddleSchool Student.” 39. Chesternon, Gilbert Keith. “The Ethics of Elfland.” 1320. Dostoevsky, Fedor. “Ghost and Eternity.” 27. Education Commission of the States. “The Higher Level Skills: Tomorrow’s ‘Basics’.” 11. Freire, Paulo. “Education Through Dialogue.” 11. Gosse, Edmund. “Untitled from Father and Son.” 4346. Hullfish, H. Gordon. “Thinking and Meaning.” 12.