Metaphysics and Biology a Critique of David Wiggins' Account of Personal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unity of Heidegger's Project

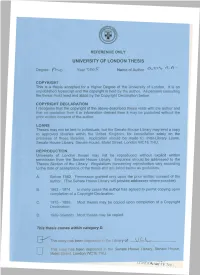

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree fV\o Year Too£ Name of Author A-A COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D. -

Towards a Methodology for Ontology Based Model Engineering

Towards a methodology for ontology based model engineering Nicola Guarino and Christopher Welty† LADSEB/CNR Padova, Italy {guarino,welty}@ladseb.pd.cnr.it http://www.ladseb.pd.cnr.it/infor/ontology/ontology.html Phone: +39 049 829 57 51 Fax: +39 049 829 57 63 † on sabbatical from Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY Abstract The Formal Tools of Ontological Analysis The philosophical discipline of Ontology is evolving towards an engineering discipline, and in this evolution the Our methodology is based on four fundamental ontologi- need for a principled methodology has clearly arisen. In cal notions, which will be discussed in this section: identity, this paper, we briefly discuss our recent work towards devel- unity, rigidity, and dependence. We shall represent the oping a methodology for ontology-based model engineering. behavior of a property with respect to these notions by This methodology builds on previous methodology efforts, means of a set of meta-properties. Our goal is to show how and is founded on important analytic notions that have been these meta-properties impose some constraints on the way drawn from Philosophy and adapted to Engineering: identity, subsumption is used to model a domain. unity, rigidity, and dependence. We demonstrate how these techniques can be used to analyze properties, which clarifies many misconceptions about taxonomies and helps bring substantial order to ontologies. Preliminaries Let’s assume we have a first-order language L0 (the model- Introduction ing language) whose intended domain is the world to be modeled, and another first order language (the meta-lan- Ontologies are becoming increasingly popular in prac- L1 tice, and the number of poor quality ontologies have made guage) whose constant symbols are the predicates of L0. -

Out of Sorts? Remedies for Theories of Object

Out of Sorts? Some Remedies for Theories of Object Concepts: A Reply to Rhemtulla and Xu Sergey V. Blok University of Texas at Austin George E. Newman Yale University Lance J. Rips Northwestern University Psychological Review, in press. Out of Sorts? / 2 Abstract Concepts of individual objects (e.g., a favorite chair or pet) include knowledge that allows people to identify these objects, sometimes after long stretches of time. In an earlier article, we set out experimental findings and mathematical modeling to support the view that judgments of identity depend on people’s beliefs about the causal connections that unite an object’s earlier and later stages. In this article, we examine Rhemtulla and Xu’s (in press) critique of the causal theory. We argue that Rhemtulla and Xu’s alternative sortal proposal is not a necessary part of identity judgments, is internally inconsistent, leads to conflicts with current theories of categories, and encounters problems explaining empirical dissociations. Previous evidence also suggests that causal factors dominate spatiotemporal continuity and perceptual similarity in direct tests. We conclude that the causal theory provides the only existing account consistent with current evidence. Keywords: Concepts Causation Sortals Object concepts Out of Sorts? / 3 Out of Sorts? Some Remedies for Theories of Object Concepts: A Reply to Rhemtulla and Xu Many objects persist over stretches of time too long for us to track perceptually. If you attend your thirtieth high school reunion, you’re bound to run into classmates like Fred Lugbagg whom you haven’t encountered since graduation and whose perceptual appearance is no more similar to the 18-year- old Lugbagg than is the appearance of most of the other males at the reunion. -

Truth and the Nature of Assertion Author(S): Huw Price Source: Mind, New Series, Vol

Mind Association Truth and the Nature of Assertion Author(s): Huw Price Source: Mind, New Series, Vol. 96, No. 382 (Apr., 1987), pp. 202-220 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Mind Association Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2255147 Accessed: 10-06-2020 17:23 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Mind Association, Oxford University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Mind This content downloaded from 132.174.255.116 on Wed, 10 Jun 2020 17:23:55 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Truth and the Nature of Assertion HUW PRICE i. David Wiggins's contribution to the Strawson Festschrift is a paper entitled 'What would be a substantial theory of truth?'.1 Wiggins begins, appropriately, with some remarks about Strawson's views on truth. In particular, he claims to find in Strawson's 1950 article on truth the view that a proper concern of the theory of truth is the task of elucidating the nature of fact-stating, empirically informative, or assertoric, uses of language; and hence of distinguishing these from uses of other sorts (distinguishing assertions from commands, for example). -

Williamson's Many Necessary Existents∗

Williamson’s Many Necessary Existents∗ Theodore Sider Analysis 69 (2009): 50–58 This note is to show that a well-known point about David Lewis’s (1986) modal realism applies to Timothy Williamson’s (1998; 2002) theory of nec- essary existents as well.1 Each theory, together with certain “recombination” principles, generates individuals too numerous to form a set. The simplest version of the argument comes from Daniel Nolan(1996). 2 Assume the following recombination principle: for each cardinal number, ν, it’s possible that there exist ν nonsets. Then given Lewis’s modal realism it follows that there can be no set of all (that is, Absolutely All) the nonsets. For suppose for reductio that there were such a set, A; let ν be A’s cardinality; and let µ be any cardinal number larger than ν. By the recombination principle, it’s possible that there exist µ nonsets; by modal realism, there exists a possible world containing, as parts, µ nonsets; each of these nonsets is a member of A; so A’s cardinality cannot have been ν. On some conceptions of what sets are, Lewis could simply accept this conclusion. But given the iterative conception of set,3 it seems that there must exist a set of all nonsets.4 According to the iterative conception, sets are “built up” in a series of “stages”. At the rst stage a set is “formed” whose members are all and only the nonsets. At subsequent stages, sets are formed whose members are sets from earlier stages. The sets, on this conception, are all and only those that are formed at some stage or other. -

Islamic Philosophy (PHIL 10197) Course Organiser: Fedor Benevich

Islamic Philosophy (PHIL 10197) Course Organiser: Fedor Benevich Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Thursday 10-12am, signup via doodle at least 8hrs in advance. Course Secretary: Ann-Marie Cowe Email: [email protected] Course Description: This course will provide a systematic introduction to key issues and debates in Islamic philosophy by focusing on the medieval period and showing its relevance for contemporary philosophical discussions. It will explore the mechanisms of the critical appropriation of the Western (Greek) philosophical heritage in the Islamic intellectual tradition and the relationship between philosophy and religion in Islam. Islamic philosophy is the missing link between ancient Greek thought and the European (medieval and early modern) philosophical tradition. It offers independent solutions to many philosophical problems which remain crucial for contemporary readers. Starting with a historical overview of the most important figures and schools, this course covers central topics of Islamic philosophy, such as (the selection of topics may vary from year to year): - faith and reason - philosophy and political authority - free will and determinism (incl. the problem of evil) - scientific knowledge and empiricism - materialism (atomism) and sortal essentialism - self-awareness, personal identity, and the immateriality of soul - proofs for God's existence Primary sources will be read in English translation. Learning Outcomes: On completion of this course, the student will be able to: 1. Demonstrate knowledge of the central issues of Islamic philosophy 2. Analyse materials independently and critically engage with other interpretations 3. Provide systematic exposition and argumentation for their views 4. Demonstrate understanding of a non-Western intellectual tradition Topics and Readings: Week 1. -

Linguistic Modal Conventionalism in the Real World

Linguistic Modal Conventionalism in the Real World Clare Due A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University March 2018 © Clare Due 2018 Statement This thesis is solely the work of its author. No part of it has previously been submitted for any degree, or is currently being submitted for any other degree. To the best of my knowledge, any help received in preparing this thesis, and all sources used, have been duly acknowledged. Word count: 88164 Clare Due 7th March 2018 Acknowledgements I am deeply grateful to Daniel Nolan for the years of support he has given me while writing this thesis. His supervision has always been challenging yet encouraging, and I have benefited greatly from his insight and depth of knowledge. His kindness and empathy also played a large role in making a difficult process much easier. My second supervisor, Alan Hájek, agreed to take me on late in my program, and has been enormously generous with his time and help since. The community of philosophers at the Australian National University provides the perfect combination of intellectual development, friendship and personal support. I consider myself very privileged to have had the opportunity to be part of that community. My research has benefited from feedback both written and verbal from many ANU philosophers, including Daniel Stoljar, Frank Jackson, Jessica Isserow, Edward Elliott, Don Nordblom, Heather Browning and Erick Llamas. I would like to offer particular thanks to Alexander Sandgren. I learned an enormous amount during the first years of my program, and a great deal of it was in conversation with Alex. -

Being Qua Being

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN part iv BEING AND BEINGS 114_Shields_Ch14.indd4_Shields_Ch14.indd 334141 11/6/2012/6/2012 66:02:56:02:56 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN 114_Shields_Ch14.indd4_Shields_Ch14.indd 334242 11/6/2012/6/2012 66:02:59:02:59 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN Chapter 14 BEING QUA BEING Christopher Shields I. Three Problems about the Science of Being qua Being ‘There is a science (epistêmê),’ says Aristotle, ‘which studies being qua being (to on hê(i) on), and the attributes belonging to it in its own right’ (Met. 1003a21–22). This claim, which opens Metaphysics IV 1, is both surprising and unsettling—sur- prising because Aristotle seems elsewhere to deny the existence of any such science and unsettling because his denial seems very plausibly grounded. He claims that each science (epistêmê) studies a unified genus (APo 87a39-b1), but he denies that there is a single genus for all beings (APo 92b14; Top. 121a16, b7–9; cf. Met. 998b22). Evidently, his two claims conspire against the science he announces: if there is no genus of being and every science requires its own genus, then there is no science of being. This seems, moreover, to be precisely the conclusion drawn by Aristotle in his Eudemian Ethics, where he maintains that we should no more look for a gen- eral science of being than we should look for a general science of goodness: ‘Just as being is not something single for the things mentioned [viz. -

Vol. 3 No. 1 January – June, 2014 Page the QUESTION of “BEING”

Vol. 3 No. 1 January – June, 2014 THE QUESTION OF “BEING” IN AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY Lucky U. OGBONNAYA, M.A. Essien Ukpabio Presbyterian Theological College, Itu, Nigeria Abstract This work is of the view that the question of being is not only a problem in Western philosophy but also in African philosophy. It, therefore, posits that being is that which is and has both abstract and concrete aspect. The work arrives at this conclusion by critically analyzing and evaluating the views of some key African philosophers with respect to being. With this, it discovers that the way that these African philosophers have postulated the idea of being is in the same manner like their Western philosophers whom they tried to criticize. This work tries to synthesize the notions of beings of these African philosophers in order to reach at a better understanding of being. This notion of being leans heavily on Asouzu’s ibuanyidanda ontology which does not bifurcate or polarize being, but harmonizes entities or realities that seem to be contrary or opposing in being. KEYWORDS: Being, Ifedi, Ihedi, Force (Vital Force), Missing Link, Muntu, Ntu, Nkedi, Ubuntu, Uwa Introduction African philosophy is a critical and rational explanation of being in African context, and based on African logic. It is in line with this that Jonathan Chimakonam avers that “in African philosophy we study reality of which being is at the center” (2013, 73). William Wallace remarks that “being signifies a concept that has the widest extension and the least comprehension” (1977, 86). It has posed a lot of problems to philosophers who tend to probe into it, its nature and manifestations. -

Just What Is the Relation Between the Manifest and the Scientific Images? Comments on Brandom

Just What is the Relation between the Manifest and the Scientific Images? Comments on Brandom I. Introduction The last half of the (long) first chapter of Brandom’s From Empiricism to Expressivism constitutes an extended argument against one half of Wilfrid Sellars’s version of scientific realism. I say ‘half’ of Sellarsian scientific realism because Brandom agrees with Sellars’s anti-instrumentalism. The half Brandom takes issue with is Sellars’s claim that the “scientific image” [SI] —an idealized, complete scientific framework for the description and explanation of all natural events and objects—possesses such ontological priority over the “manifest image” [MI]—itself an idealization of the ‘commonsense’ framework of persons and things in terms of which we currently experience ourselves and the world—that it will come to replace the MI in all matters of explanation and description. Brandom’s argument against this Sellarsian idea is rather roundabout. First, he traces Sellars’s distinction between the MI and the SI back to the Kantian distinction between phenomena and noumena. Then he argues against several attempts to understand identity claims across disparate frameworks. Neither, claims Brandom, will permit us to identify objects across the MI/SI divide. But if we cannot identify the objects of concern across the frameworks, then a shift from the MI to the SI is not a form of replacement of one framework by a better, but simply a change of subject that poses no threat to the MI. The overall argument of the chapter is that, though what Sellars made of the Kantian notion of a category is a very Good Idea, Sellars’s assimilation of scientific realism to a kind of transcendental realism in Kant’s sense, is a Bad Idea with a muddled basis and unworkable consequences. -

The Philosophical Development of Gilbert Ryle

THE PHILOSOPHICAL DEVELOPMENT OF GILBERT RYLE A Study of His Published and Unpublished Writings © Charlotte Vrijen 2007 Illustrations front cover: 1) Ryle’s annotations to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus 2) Notes (miscellaneous) from ‘the red box’, Linacre College Library Illustration back cover: Rodin’s Le Penseur RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN The Philosophical Development of Gilbert Ryle A Study of His Published and Unpublished Writings Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Wijsbegeerte aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. F. Zwarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 14 juni 2007 om 16.15 uur door Charlotte Vrijen geboren op 11 maart 1978 te Rolde Promotor: Prof. Dr. L.W. Nauta Copromotor: Prof. Dr. M.R.M. ter Hark Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. Dr. D.H.K. Pätzold Prof. Dr. B.F. McGuinness Prof. Dr. J.M. Connelly ISBN: 978-90-367-3049-5 Preface I am indebted to many people for being able to finish this dissertation. First of all I would like to thank my supervisor and promotor Lodi Nauta for his comments on an enormous variety of drafts and for the many stimulating discussions we had throughout the project. He did not limit himself to deeply theoretical discussions but also saved me from grammatical and stylish sloppiness. (He would, for example, have suggested to leave out the ‘enormous’ and ‘many’ above, as well as by far most of the ‘very’’s and ‘greatly’’s in the sentences to come.) After I had already started my new job outside the academic world, Lodi regularly – but always in a pleasant way – reminded me of this other job that still had to be finished. -

]) = 9X Snow(X)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8548/p-x-y-exists-y-9x-snow-x-1398548.webp)

P(X)]( Y Exists(Y)]) = 9X Snow(X)

Existential sentences without existential quanti cation Louise McNally Universitat Pomp eu Fabra 1. Intro duction 1 In a chapter on existence statements in Individuals: An Essay in Descriptive Metaphysics, Strawson makes the following observation: we can...admit the p ossibility of another formulation of existentially quanti ed statement[s], and, with it, the p ossibility of another use of the word `exists'....We can, that is to say, reconstrue every such quanti ed prop osition as a sub ject-predicate prop osition in whichthe sub ject is a prop erty or concept and in which the predicate declares, or denies, its instantiation. (Strawson 1959:241) In other words, there are twoways to express a prop osition whose truth entails the existence of some token entity (or particular, to use Strawson's terminology). Supp ose we take the following there-existential sentence as an example: (1) There was snow. We might, mo difying slightly the analysis in Barwise and Co op er 1981, inter- pret There was as an existence predicate and snow as an existential quanti er over particulars (represented logically in (2)): (2) P [9x[snow(x) ^ P (x)](y [exists(y )]) = 9x[snow(x) ^ exists(x)] Alternatively,we might (essentially equivalently) interpret Therewasas if it were synonymous with the predicate to be instantiated, a predicate that holds of expressions interpreted as prop erties or as what Strawson calls nonparticulars, e.g. as in (3)a. Presumably,itwould b e true that the snow-prop erty is instantiated i some particular, one that is a quantity of snow, exists (i.e.