Semantic Properties and the Computational Model of Mind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Things and Places the Jean Nicod Lectures Franc¸Ois Recanati, Editor

Things and Places The Jean Nicod Lectures Franc¸ois Recanati, editor The Elm and the Expert: Mentalese and Its Semantics, Jerry A. Fodor (1994) Naturalizing the Mind, Fred Dretske (1995) Strong Feelings: Emotion, Addiction, and Human Behavior, Jon Elster (1999) Knowledge, Possibility, and Consciousness, John Perry (2001) Rationality in Action, John R. Searle (2001) Varieties of Meaning, Ruth Garrett Millikan (2004) Sweet Dreams: Philosophical Obstacles to a Science of Consciousness, Daniel C. Dennett (2005) Reliable Reasoning: Induction and Statistical Learning Theory, Gilbert Harman and Sanjeev Kulkarni (2007) Things and Places: How the Mind Connects with the World, Zenon W. Pylyshyn (2007) Things and Places How the Mind Connects with the World Zenon W. Pylyshyn A Bradford Book The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England ( 2007 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any elec- tronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] or write to Special Sales Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142. This book was set in Stone Serif and Stone Sans on 3B2 by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong, and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pylyshyn, Zenon W. Things and places : how the mind connects with the world / by Zenon W. Pylyshyn. p. cm.—(The Jean Nicod lectures) ‘‘A Bradford book.’’ Includes bibliographical references and indexes. -

The Problem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions Edward Matusek University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Matusek, Edward, "The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3733 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Problem of Evil in Augustine’s Confessions by Edward A. Matusek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Thomas Williams, Ph.D. Roger Ariew, Ph.D. Joanne Waugh, Ph.D. Charles B. Guignon, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 14, 2011 Keywords: theodicy, privation, metaphysical evil, Manichaeism, Neo-Platonism Copyright © 2011, Edward A. Matusek i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iii Chapter One: Introduction to Augustine’s Confessions and the Present Study 1 Purpose and Background of the Study 2 Literary and Historical Considerations of Confessions 4 Relevance of the Study for Various -

Author Title 1 ? Mennyi? Szamok a Termeszetben 2 A. DAVID REDISH

Author Title 1 ? Mennyi? Szamok a termeszetben 2 A. DAVID REDISH. BEYOND THE COGNITIVE MAP : FROM PLACE CELLS TO EPISODIC MEMORY 3 Aaron C.T.Smith Cognitive mechanisms of belief change 4 Aaron L.Berkowitz The improvising mind: cognition and creativity in the musical moment 5 AARON L.BERKOWITZ. THE IMPROVISING MIND : COGNITION AND CREATIVITY IN THE MUSICAL MOMENT 6 AARON T. BECK. COGNITIVE THERAPY AND THE EMOTIONAL DISORDERS 7 Aaron Williamon Musical excellence: strategies and techniques to enhance performance 8 AIDAN FEENEY, EVAN HEIT. INDUCTIVE REASONING : EXPERIMENTAL, DEVELOPMENTAL, AND COMPUTATIONAL APPROACHES 9 Alain F. Zuur, Elena N. Ieno, Erik H.W.G.Meesters A beginner`s guide to R 10 Alain F. Zuur, Elena N. Ieno, Erik H.W.G.Meesters A beginner`s guide to R 11 ALAN BADDELEY, Michael W. EYSENCK, AND Michael MEMORYC. ANDERSON. 12 ALAN GILCHRIST. SEEING BLACK AND WHITE 13 Alan Merriam The anthropology of music RYTHMES ET CHAOS DANS LES SYSTEMES BIOCHIMIQUES ET CELLULAIRES. ENGLISH. BIOCHEMICAL 14 ALBERT GOLDBETER OSCILLATIONS AND CELLULAR RHYTHMS : THE MOLECULAR BASES OF PERIODIC AND CHAOTIC BEHAVIOUR 15 Albert S Bregman Auditory scene analysis: the perceptual organization of sound 16 Albert-Laszlo Barabasi Network Science 17 Alda Mari, Claire Beyssade, Fabio del Prete Genericity 18 Alex Mesoudi Cultural Evolution: how Darwinian theory can explain human culture and synthesize the social sciences 19 Alexander Easton The cognitive neuroscience of social behaviour. 20 ALEXANDER TODOROV Face Value the irresistible influence of first impression 21 ALEXANDER TODOROV, Susan T. FISKE & DEBORAHSOCIAL PRENTICE. NEUROSCIENCE : TOWARD UNDERSTANDING THE UNDERPINNINGS OF THE SOCIAL MIND 22 ALEXANDRA HOROWITZ INSIDE OF A DOG : WHAT DOGS SEE, SMELL, AND KNOW 23 Alfred Blatter Revisiting music theory: a guide to the practice 24 Alison Gopnik Bolcsek a bolcsoben: hogyan gondolkodnak a kisbabak 25 Alison Gopnik A babak filozofiaja 26 ANDREW DUCHOWSKI EYE TRACKING METHODOLOGY : THEORY AND PRACTICE 27 Andrew Gelman Bayesian Data Analysis 28 ANDREW GELMAN .. -

(CGE Marcoussis), G. Huet

The FINITE STRING Newsletter Announcements Announcements The Program Committe consists of: James Allen, Norm Badler, Mike Bauer, Wayne Davis, Mark Fox, Bill Havens, Hector Levesque, Charles Morgan, John NELS Meeting and Workshop Mylopoulos, Zenon Pylyshyn, Reid Smith, and Doug The Twelfth Annual Meeting of the North-Eastern Skuce. The Proceedings Editor is Brian Funt. Linguistic Society will be held November 6-8, 1981, at Correspondence should be addressed to: the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Plans are Gordon McCalla, General Chairman also being made to hold a workshop immediately be- CSCSI/SCEIO Conference fore the Meeting on the topic "Free Word-Order and Department of Computational Science Syntactic Configuration". Questions to be addressed University of Saskatchewan at the workshop include: what are the functions of Saskatoon, Sask. CANADA S7N 0W0 word-order in syntax and semantics? what degrees of freedom are there of word-order? how should the Nick Cercone, Program Chairman different functions and degrees of word-order be ex- CSCSI/SCEIO Conference pressed within a theory of universal grammar? Computing Science Department Simon Fraser University For further information contact: Burnaby, B.C. CANADA V5A 1S6 NELS Committee Department of Linguistics and Philosophy M.I.T., 20C-128 ECAI-82: Call for Papers Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 The 1982 European Conference on Artificial Intel- ligence will be held July 12-14, 1982, in Orsay, France CSCSI/SCEIO: Call for Papers (just after COLING-82). The conference is sponsored by the Society for the Study of Artificial Intelligence The Fourth National Conference of the Canadian and the Simulation of Behavior (AISB), and succeeds Society for Computational Studies of Intelligence/ to the AISB meetings on Artificial Intelligence held at Soci6t6 Canadienne pour Etudes d'intelligence par Brighton (1974), Edinburgh (1976), Hamburg (1978), Ordinateur will be held at the University of Saskatche- and Amsterdam (1980). -

Gareth B. Matthews Curriculum Vitae1

1 Gareth B. Matthews curriculum vitae1 Born 8 July 1929; married; three children; six grandchildren. Died 17 April 2011; survived by wife, three children, and seven grandchildren. Education Franklin College (Indiana) 1947-51 A.B. (1951) Middlebury German School Summer 1950 Harvard University 1951-52 A.M. (1952) University of Tübingen Summer 1952 Free University of Berlin 1952-53 Harvard University 1957-60 Ph.D. (1961) Military Service United States Naval Reserve Active duty: 1954-57, served to rank of (full) Lieutenant Academic Appointments University of Virginia Assistant Professor 1960-61 University of Minnesota Assistant Professor 1961-65 Associate Professor 1965-69 University of Massachusetts Professor 1969-2005 Professor emeritus 2005-2011 Visiting Professorships Amherst College (1973, 1998, 2006, 2007) Brown University (1988, 2005) University of Calgary Summer School (1978, 1987) Harvard Summer School (1968, 1976) University of Minnesota (1981) Mount Holyoke College (1977, 1991, 2006) Smith College (1972, 1974, 1988, 2008) Tufts University (2008) Fellowships and Scholarships Harvard University Graduate School Scholarship (1951-52) George Santayana Postdoctoral Fellowship (1967-68) Rotary Foundation Fellowship (1952-53) National Endowment for the Humanities Research Fellowships (1982-83; 1989-90) Institute for Advanced Study Member (January – June, 1986 for project: Augustine and Descartes: philosophy from a first-person perspective) Presentations A. To the American Philosophical Association 2 Eastern Division: 1965, 1970, 1972, 1974, 1976, 1980, 1984, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2005 Central Division: 1962, 1965, 1967, 1970, 1972, 1973, 1980, 1982, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2002 Pacific Division: 1974, 1979, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1992, 1994, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2003, 2004 B. -

Proposal for an APA Grant to Support the Development of “What's the Big

Grant Proposal “What’s the Big Idea?” Page 1 Proposal for an APA Grant to support the Development of “What’s the Big Idea?” Thomas E. Wartenberg, Project Director ABSTRACT What’s the Big Idea? is a website that will be based on approximately 90-minutes of film and a comprehensive curriculum introducing ethics to middle school children through feature film segments that are introduced and discussed by philosophers. The website will be composed of five chapters: on bullying, lying, peer pressure, friendship, and environmental ethics. Each chapter will feature video clips from popular films, clips of philosophers introducing the issue, and support materials facilitating discussion in the classroom. The materials will guide a variety of activities before, during, and after the presentation of the film clips. We have nearly finished a rough version of Chapter 1 on “Bullying ” and are requesting $10,000 from The American Philosophical Association to produce the second and third 15-minute sections on the topics of “Lying” and “Friendship” and to develop the accompanying curriculum. The ethical issues of bullying, peer pressure, friendship, lying and environmental action were selected by middle school students in three different schools as the most relevant ethical issues in their lives. Grant Proposal “What’s the Big Idea?” Page 2 1. Purpose of the Project Although the teaching of philosophy in pre-college classrooms has been expanding lately, most programs for doing so have focused on either high school or elementary school classrooms. What’s the Big Idea? will provide middle school teachers with all the materials necessary for having classrooms discussions of five important ethical issues: bullying, lying, peer pressure, friendship, and environmental ethics. -

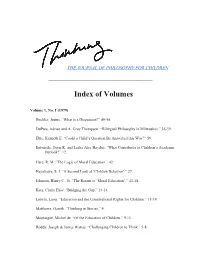

Index of Thinking Volumes

THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY FOR CHILDREN __________________________________________________ Index of Volumes Volume 1, No. 1 (1979) Buchler, Justus. “What is a Discussion?” 4954. DuPuis, Adrian and A. Gray Thompson. “Bilingual Philosophy in Milwaukee.” 3539. Eble, Kenneth E. “Could a Child’s Question Be Answered this Way?” 59. Entwistle, Doris R. and Leslie Alec Hayduc. “What Contributes to Children’s Academic Outlook?” 12. Hare, R. M. “The Logic of Moral Education.” 42. Hayakawa, S. I. “A Second Look at ‘Childish Behavior’.” 27. Johnson, Henry C., Jr. “The Return to ‘Moral Education’.” 4148. Katz, Claire Elise. “Bridging the Gap,” 1314. Letwin, Leon. “Education and the Constitutional Rights for Children.” 1119. Matthews, Gareth. “Thinking in Stories.” 4. Montaigne, Michel de. “Of the Education of Children.” 911. Roddy, Joseph & James Watras. “Challenging Children to Think.” 58. Simon, Charlann. “Philosophy for Students with Learning Disabilities.” 2133. Wagner, Paul A.“Philosophy, Children, and ‘Doing Science’.” 5557. Worsfold, Victor L. “What Claims Can Children Make?” 13. Volume 1, No. 2 (1979) Aman, Kenneth and Sister Anna Maria Hartman. “Philosophy for Children in a SpanishSpeaking Contest.” 410. Barr, Donald. “How Important are Categories for Children.” 11. Berman, Ronald. “On Writing Good.” 12. Brent, Frances. “Philosophy and the MiddleSchool Student.” 39. Chesternon, Gilbert Keith. “The Ethics of Elfland.” 1320. Dostoevsky, Fedor. “Ghost and Eternity.” 27. Education Commission of the States. “The Higher Level Skills: Tomorrow’s ‘Basics’.” 11. Freire, Paulo. “Education Through Dialogue.” 11. Gosse, Edmund. “Untitled from Father and Son.” 4346. Hullfish, H. Gordon. “Thinking and Meaning.” 12. -

Things and Places: How the Mind Connects with the World

Things and Places: How the Mind Connects With the World Zenon W. Pylyshyn Rutgers Center for Cognitive Science Forthcoming, 2007, MIT Press (Jean Nicod Lecture Series) i 11/26/2006 Table of contents Preface & Acknowledgements Chapter 1. Introduction to the Problem: Connecting Perception and the World 1.1 Background 1.2 What’s the problem of connecting the mind with the world? Doesn’t every computational theory of vision do that ? 1.3 The need for a direct way of referring to certain individual tokens in a scene 1.3.1 Incremental construction of representations (and a brief sketch of FINSTs) 1.3.2 Using descriptions to pick out individuals 1.3.3 The need for demonstrative reference in perception 1.4 Some empirical phenomena illustrating the role of Indexes 1.4.1 Tagging/marking individual objects for attentional priority 1.4.2 Argument binding 1.4.3 Subitizing 1.4.4 Subset selection 1.5 What are we to make of such empirical demonstrations? Chapter 2. Indexing and tracking individuals 2.1 Individuating and tracking 2.2 Indexes and primitive tracking 2.3 What goes on in MOT? 2.3.1 FINSTs and Object Files 2.3.2 The explanation of tracking 2.4 Other empirical and theoretical issues surrounding MOT 2.4.1 Do we track by keeping a record of locations? 2.4.2 Can we select objects voluntarily? 2.4.3 Tracking without keeping track of labels 2.4.4 Nonconceptual individuation without reference? 2.5 Infants capacity for individuating and tracking objects 2.6 Summary and Implications for the Foundations of Cognitive Science 2.6.1 Review: Nonconceptual functions and Natural Constraints 2.6.2 Summary: Why are FINSTs needed? Chapter 3. -

Intentional Disruption Expanding Access to Philosophy

Intentional Disruption Expanding Access to Philosophy Edited by Stephen Kekoa Miller Oakwood Friends School; Marist College Series in Philosophy Copyright © 2021 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Philosophy Library of Congress Control Number: 2021938620 ISBN: 978-1-64889-191-5 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press using elements designed by Timothy Dykes, unsplash.com. Table of contents Foreword v Wendy C. Turgeon St. Joseph’s College Chapter 1 What to Consider when Considering a Pre-college Philosophy Program: Frequently Asked Questions from Those considering -

CURRICULUM VITAE John Bickle December 2020

CURRICULUM VITAE John Bickle December 2020 Mailing Address: Department of Philosophy and Religion P.O. Box JS Mississippi State University Mississippi State, MS 39762 (662) 325-2382 fax: (662) 325-3340 E-mail Addresses: [email protected] URLs: http://www.philosophyandreligion.msstate.edu/faculty/bickle.php https://www.umc.edu/Education/Schools/Medicine/Basic_Science/Neurobiology/John_Bi ckle,_PhD.aspx ___________________________________________________________________________ CURRENT ACADEMIC POSITIONS Professor (Tenured) of Philosophy Mississippi State University Affiliate Faculty Department of Neurobiology and Anatomical Sciences University of Mississippi Medical Center EDUCATION B.A. University of California, Los Angeles, June 1983 M.A., Ph.D. University of California, Irvine, June 1989 Field: Philosophy; Scientific Concentration: Neurobiology. Doctoral Dissertation: Toward a Scientific Reformulation of the Mind-Body Problem AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Philosophy of Neuroscience, Philosophy of Science (especially Scientific Reductionism), Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Cognition and Consciousness AREAS OF COMPETENCE Moral Psychology and the Moral Virtues, Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI). Logical Positivism (especially the Philosophy of Rudolph Carnap), Libertarian Political Philosophy ______________________________________________________________________________ PROFESSIONAL PUBLICATIONS (94) BOOKS (4) 2014 Engineering the Next Revolution in Neuroscience. (Co-authors: Alcino J. Silva and Anthony Landreth). -

Pylyshyn: Mental Imagery

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2002) 25, 157–238 Printed in the United States of America Mental imagery: In search of a theory Zenon W. Pylyshyn Rutgers Center for Cognitive Science, Rutgers University, Busch Campus, Piscataway, NJ 08854-8020. [email protected] http://ruccs.rutgers.edu/faculty/pylyshyn.html Abstract: It is generally accepted that there is something special about reasoning by using mental images. The question of how it is spe- cial, however, has never been satisfactorily spelled out, despite more than thirty years of research in the post-behaviorist tradition. This article considers some of the general motivation for the assumption that entertaining mental images involves inspecting a picture-like object. It sets out a distinction between phenomena attributable to the nature of mind to what is called the cognitive architecture, and ones that are attributable to tacit knowledge used to simulate what would happen in a visual situation. With this distinction in mind, the paper then considers in detail the widely held assumption that in some important sense images are spatially displayed or are depictive, and that examining images uses the same mechanisms that are deployed in visual perception. I argue that the assumption of the spatial or depictive nature of images is only explanatory if taken literally, as a claim about how images are physically instantiated in the brain, and that the literal view fails for a number of empirical reasons – for example, because of the cognitive penetrability of the phenomena cited in its favor. Similarly, while it is arguably the case that imagery and vision involve some of the same mechanisms, this tells us very little about the nature of mental imagery and does not support claims about the pictorial nature of mental images. -

Philosophy 501/CCT 603 Foundations of Philosophical Thought Arthur

Philosophy 501/CCT 603 Foundations of Philosophical Thought Arthur Millman Fall 2018 Office: W/5/020 Wednesdays 7:00 Phone: (617) 287-6538 Room: W/4/170 E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: W 5-7, Th 7-8 and by arrangement at other times (face-toface or online) This course introduces graduate students in the Critical and Creative Thinking Graduate Program and other graduate programs to some of the traditional problems and methods of philosophical inquiry. It also relates philosophy to concerns about good thinking, educational reform, and teaching for effective thinking and considers how to infuse philosophical thinking into workplaces, school curricula, other academic disciplines, and our own lives. We will become acquainted with several central philosophical problems. What is it to think philosophically? Why should one be moral? What is justice? What is knowledge? How can concrete moral issues such as abortion, human embryo research, and war be thought through? We will not find final answers to these questions. Rather we will: (1) seek to understand why these are such important and open questions, (2) begin to explore ways of answering them, (3) consider how to draw students and others into further engagement with philosophical thinking, and (4) find connections between such questions and other questions we have. The course provides a basis for further work in CCT, Education or many other fields. The course will proceed primarily through discussion and writing in a (virtual) classroom community of inquiry. You are expected to contribute to the learning experience of the class as well as to gain useful insights from others.