Cerebral Pleasures; Children's Literature And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emerald City of Oz by L. Frank Baum Author of the Road to Oz

The Emerald City of Oz by L. Frank Baum Author of The Road to Oz, Dorothy and The Wizard in Oz, The Land of Oz, etc. Contents --Author's Note-- 1. How the Nome King Became Angry 2. How Uncle Henry Got Into Trouble 3. How Ozma Granted Dorothy's Request 4. How The Nome King Planned Revenge 5. How Dorothy Became a Princess 6. How Guph Visited the Whimsies 7. How Aunt Em Conquered the Lion 8. How the Grand Gallipoot Joined The Nomes 9. How the Wogglebug Taught Athletics 10. How the Cuttenclips Lived 11. How the General Met the First and Foremost 12. How they Matched the Fuddles 13. How the General Talked to the King 14. How the Wizard Practiced Sorcery 15. How Dorothy Happened to Get Lost 16. How Dorothy Visited Utensia 17. How They Came to Bunbury 18. How Ozma Looked into the Magic Picture 19. How Bunnybury Welcomed the Strangers 20. How Dorothy Lunched With a King 21. How the King Changed His Mind 22. How the Wizard Found Dorothy 23. How They Encountered the Flutterbudgets 24. How the Tin Woodman Told the Sad News 25. How the Scarecrow Displayed His Wisdom 26. How Ozma Refused to Fight for Her Kingdom 27. How the Fierce Warriors Invaded Oz 28. How They Drank at the Forbidden Fountain 29. How Glinda Worked a Magic Spell 30. How the Story of Oz Came to an End Author's Note Perhaps I should admit on the title page that this book is "By L. Frank Baum and his correspondents," for I have used many suggestions conveyed to me in letters from children. -

The Lost Princess of Oz

The Lost Princess of Oz By L. Frank Baum THE LOST PRINCESS CHAPTER 1 A TERRIBLE LOSS There could be no doubt of the fact: Princess Ozma, the lovely girl ruler of the Fairyland of Oz, was lost. She had completely disappeared. Not one of her subjects—not even her closest friends—knew what had become of her. It was Dorothy who first discovered it. Dorothy was a little Kansas girl who had come to the Land of Oz to live and had been given a delightful suite of rooms in Ozma's royal palace just because Ozma loved Dorothy and wanted her to live as near her as possible so the two girls might be much together. Dorothy was not the only girl from the outside world who had been welcomed to Oz and lived in the royal palace. There was another named Betsy Bobbin, whose adventures had led her to seek refuge with Ozma, and still another named Trot, who had been invited, together with her faithful companion Cap'n Bill, to make her home in this wonderful fairyland. The three girls all had rooms in the palace and were great chums; but Dorothy was the dearest friend of their gracious Ruler and only she at any hour dared to seek Ozma in her royal apartments. For Dorothy had lived in Oz much longer than the other girls and had been made a Princess of the realm. Betsy was a year older than Dorothy and Trot was a year younger, yet the three were near enough of an age to become great playmates and to have nice times together. -

Lewis Carroll at Play •}'Y It, -Pjf55 Dhhl )')~, I

CQS€.; RS 3b Lewis Carroll at Play •}'Y It, -PJf55 dhhl )')~, I A Thesis Presented to the Chancellor's Scholars Council of The University ofNorth Carolina at Pembroke In Partial Fulfillment Ofthe Requirements for Completion of The Chancellor's Scholars Program By James Nichols December 4,2001 Faculty Advisor's Approval ~ Faculty Advisor's Approvaldi: Faculty Advisor's APproi :£ Date ~ 296640 Lewis Carroll at Play Chancellor's Scholars Paper Outline I. Introduction A. Popularity ofthe Alice books B. Lewis Carroll background & summary ofAlice books C. Lewis Carroll put Alice books together for insight D. Lewis Carroll incorporated math, logic and games in Through the Looking Glass and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, which benefits computer scientists and mathematicians. II. Mathematics in Alice books relates to computer science A. Properties 1. Identity 2. Inverses 3. No solution problems (nonsense) 4. Rules not absolute-always an exception B. Symmetry C. Dimensions D. Meaning ofmathematical phrases E. Null class F. Math puzzles 1. Multiplying 2. Alice's running 3. Line puzzle 4. Time 5. Zero-sum game 6. Transformations G. Mathematical puns m. Logic in the Alice books relates to computer science A. Concepts being broken down B. Humpty Dumpty chooses what words mean C. Need for Order D. Alice as a logician E. Logic ofa child F. Don't assume anything G. Symbols N. Games in the Alice books relates to computer science A. Cards B. Chess C. Acrostics D. Doublets E. Syzgies F. Magic Tricks 1. Fan 2. Apple 3. Magic Number G. Mazes H. Carroll's Games V. What Lewis Carroll offers to Computer Science and Mathematics today A. -

Fantasy Football University Chapter 1

Fantasy Football University Chapter 1 What is Fantasy Football? Fantasy Football puts you in charge and gives you the opportunity to become the coach, owner, and general manager of your own personal football franchise. You'll draft a team of pro football players and compete against other team owners for your league's championship. The game and its rules are designed to mimic pro football as much as possible, so you'll live the same thrills and disappointments that go along with a football season. And your goal is simple: build a complete football team, dominate the competition and win your league's championship. Why should you be playing Fantasy Football? The game is easy to learn and fun to play. You'll become more knowledgeable about football than ever before. It does not take a huge commitment to be competitive and requires only as much time as you'd like to invest. And you don't have to be a die-hard fan to enjoy playing. In fact, most people who are trying Fantasy Football for the first time are casual fans. Chapter 2 Team & League Team name: The first step to getting started is creating a name for your new team. This is how you and your team will be identified throughout the season so get creative and have a little fun. Join or create a league: Your competition will be made up of the other owners in your league. The number of teams in a Fantasy Football league can vary but should always be an even number. -

The Problem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions Edward Matusek University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Matusek, Edward, "The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3733 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Problem of Evil in Augustine’s Confessions by Edward A. Matusek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Thomas Williams, Ph.D. Roger Ariew, Ph.D. Joanne Waugh, Ph.D. Charles B. Guignon, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 14, 2011 Keywords: theodicy, privation, metaphysical evil, Manichaeism, Neo-Platonism Copyright © 2011, Edward A. Matusek i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iii Chapter One: Introduction to Augustine’s Confessions and the Present Study 1 Purpose and Background of the Study 2 Literary and Historical Considerations of Confessions 4 Relevance of the Study for Various -

Press Release FULL NEW CAST ANNOUNCED for RECORD-BREAKING WICKED UK TOUR NEW CAST BEGINS 16 SEPTEMBER at LIVERPOOL EMPIRE

Monday 4 August 2014 Press Release FULL NEW CAST ANNOUNCED FOR RECORD-BREAKING WICKED UK TOUR NEW CAST BEGINS 16 SEPTEMBER AT LIVERPOOL EMPIRE WICKED, the global musical phenomenon that tells the incredible untold story of the Witches of Oz, is pleased to announce that Ashleigh Gray (Elphaba), Emily Tierney (Glinda), Samuel Edwards (Fiyero), Marilyn Cutts (Madame Morrible), Steven Pinder (The Wizard and Doctor Dillamond), Carina Gillespie (Nessarose), Richard Vincent (Boq), Jacqueline Hughes (Standby Elphaba), Joe Atkinson, Joshua Berg, Chrissy Brooke, Ben Carruthers, Harrison Clark, Lauren Ellis-Steele, Oliver Evans, Victoria Farley, Natasha Ferguson, Zoë George, Natalie Green, Will Knights, Sophie Leigh-Griffin, Candy Marriot, Tom Mather, Brian McCann, Ashley Morgan-Davies, Stephanie Powell, Wendy-Lee Purdy, Elisha Sherman, Grant Thresh, Hannah Veerapen and Danny Whitehead will star in the record-breaking UK Tour from Tuesday 16 September 2014 at Liverpool Empire Theatre. The tour is currently at Birmingham Hippodrome (until 6 September 2014) and continues to Liverpool Empire Theatre (16 September to 11 October 2014); Southampton Mayflower Theatre (21 October to 15 November 2014); Edinburgh Playhouse (19 November 2014 to 10 January 2015); Plymouth Theatre Royal (20 January to 14 February 2015); Bristol Hippodrome (18 February to 21 March 2015); Sunderland Empire Theatre (31 March to 25 April 2015); Aberdeen His Majesty’s Theatre (5 to 30 May 2015) and concludes at The Lowry in Salford (3 June to 25 July 2015). Tickets are now on sale at all venues and can be booked via www.WickedTheMusical.co.uk Acclaimed as “quite simply, the best musical I’ve ever seen” (Yorkshire Evening Post), the tour has already broken Box Office records and won multiple five star reviews across England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland. -

The Low-Status Character in Shakespeare's Comedies Linda St

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 5-1-1973 The Low-Status Character in Shakespeare's Comedies Linda St. Clair Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation St. Clair, Linda, "The Low-Status Character in Shakespeare's Comedies" (1973). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1028. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1028 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARCHIVES THE LOW-STATUS CHARACTER IN SHAKESPEAREf S CCiiEDIES A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bov/ling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Linda Abbott St. Clair May, 1973 THE LOW-STATUS CHARACTER IN SHAKESPEARE'S COMEDIES APPROVED >///!}<•/ -J?/ /f?3\ (Date) a D TfV OfThesis / A, ^ of the Grafduate School ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With gratitude I express my appreciation to Dr. Addie Milliard who gave so generously of her time and knowledge to aid me in this study. My thanks also go to Dr. Nancy Davis and Dr. v.'ill Fridy, both of whom painstakingly read my first draft, offering invaluable suggestions for improvement. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii INTRODUCTION 1 THE EARLY COMEDIES 8 THE MIDDLE COMEDIES 35 THE LATER COMEDIES 8? CONCLUSION 106 BIBLIOGRAPHY Ill iv INTRODUCTION Just as the audience which viewed Shakespeare's plays was a diverse group made of all social classes, so are the characters which Shakespeare created. -

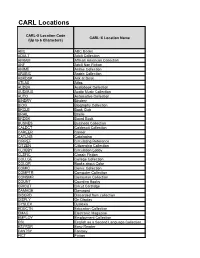

CARL Locations

CARL Locations CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) ABC ABC Books ADULT Adult Collection AFRAM African American Collection ANF Adult Non Fiction ANIME Anime Collection ARABIC Arabic Collection ASKDSK Ask at Desk ATLAS Atlas AUDBK Audiobook Collection AUDMUS Audio Music Collection AUTO Automotive Collection BINDRY Bindery BIOG Biography Collection BKCLB Book Club BRAIL Braille BRDBK Board Book BUSNES Business Collection CALDCT Caldecott Collection CAREER Career CATLNG Cataloging CIRREF Circulating Reference CITZEN Citizenship Collection CLOBBY Circulation Lobby CLSFIC Classic Fiction COLLGE College Collection COLOR Books about Color COMIC Comic Collection COMPTR Computer Collection CONSMR Consumer Collection COUNT Counting Books CRICUT Cricut Cartridge DAMAGE Damaged DISCRD Discarded from collection DISPLY On Display DYSLEX Dyslexia EDUCTN Education Collection EMAG Electronic Magazine EMPLOY Employment Collection ESL English as a Second Language Collection ESYRDR Easy Reader FANTSY Fantasy FICT Fiction CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) GAMING Gaming Collection GENEAL Genealogy Collection GOVDOC Government Documents Collection GRAPHN Graphic Novel Collection HISCHL High School Collection HOLDAY Holiday HORROR Horror HOURLY Hourly Loans for Pontiac INLIB In Library INSFIC Inspirational Fiction INSROM Inspirational Romance INTFLM International Film INTLNG International Language Collection JADVEN Juvenile Adventure JAUDBK Juvenile Audiobook Collection JAUDMU Juvenile Audio Music Collection -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

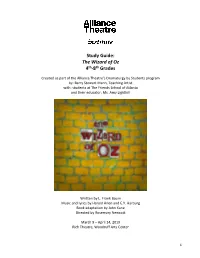

The Wizard of Oz 4Th-8Th Grades

Study Guide: The Wizard of Oz 4th-8th Grades Created as part of the Alliance Theatre’s Dramaturgy by Students program by: Barry Stewart Mann, Teaching Artist with: students at The Friends School of Atlanta and their educator: Ms. Amy Lighthill Written by L. Frank Baum Music and lyrics by Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg Book adaptation by John Kane Directed by Rosemary Newcott March 9 – April 14, 2019 Rich Theatre, Woodruff Arts Center 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pre- and Post-Show Questions ________________________________________________ pg. 3 About the Director __________________________________________________________ pg. 4 Curriculum Standards _______________________________________________________ pg. 5 Synopsis __________________________________________________________________ pg. 5 About the Author ___________________________________________________________ pg. 6 About the Film ____________________________________________________________ pg. 6 • Fun Film Facts ____________________________________________________ pg. 7 • The Wizard of Oz Time Line _________________________________________ pg. 8 Character Profiles on Oztagramchatbook _______________________________________ pg. 9 Folk Art __________________________________________________________________ pg. 10 Themes • (There’s No Place Like) Home ________________________________________ pg. 11 • (Somewhere Over the) Rainbow ______________________________________ pg. 12 • The Hero’s Journey (a Debate) _______________________________________ pgs. 13-14 STEAM Connections _________________________________________________________ -

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

Philosophical Fiction? on J. M. Coetzee's Elizabeth Costello

Philosophical Fiction? On J. M. Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello Robert Pippin University of Chicago i he modern fate of the ideal of the beautiful is deeply intertwined with the beginnings of European aesthetic modernism. More specifically, from the point of view of modernism, commitment to the ideal of the beautiful is often understood to be both Tirrelevant and regressive. This claim obviously requires a gloss on “modernity” and “modern- ism.” Here is a conventional view. European modernism in the arts can be considered a reaction to the form of life coming into view in the mid-nineteenth century as the realization of early Enlightenment ideals: that is, the supreme cognitive authority of modern natural science, a new market economy based on the accumulation of private capital, rapid urbanization and industri- alization, ostensibly democratic institutions still largely controlled by elites, the privatization of religion and so the secularization of the public sphere. The modernist moment arose from some sense that this form of life was so unprecedented in human history that art’s very purpose or rationale, its mode of address to an audience, had to be fundamentally rethought. Nothing about the purpose or value of art, as it had been understood, could be taken for granted any longer, and the issue was: what kind of art, committed to what ideal, could be credible in such a world (if any)? A response to such a development was taken by some to require a novelty, experimentation and formal radicality so extreme as to seem unintelligible to its “first responders.” Modernism was to be an anti-Romanticism, rejecting lyrical expression of the inner in favor of impersonal- ity, or of multiple, fractured authorial personae, attempting an ironic distancing, experimental 2 republics of letters innovation, and, in so-called high modernism, assuming an elite position, sometimes with mul- tiple, obscure allusions, defiantly resistant to commercialization or a public role.