White Students and Activists Involved in the Black Power Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News From: Oakland Public Library for IMMEDIATE RELEASE

News from: Oakland Public Library FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 4, 2019 AAMLO Digitizes Black Panther Party Films All digitized films can be viewed online Web: http://oaklandlibrary.org/news/2019/04/aamlo-digitizes-black-panther- party-films Oakland, CA – In April 2018, the African American Museum & Library at Oakland was awarded a Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) Recordings at Risk grant to digitize and provide access online to 98 films documenting the Black Panther Party (BPP) and student and union protest movements of the late 1960s and 1970s from the Henry J. Williams Jr. Film Collection. Those films are now available online in AAMLO’s Internet Archive page or in the finding aid for the Henry J. Williams Jr. Film Collection in the Online Archive of Media Contacts: California. Matt Berson The films include footage shot by the documentary film collective Newsreel, an Public Information Officer organization founded in New York City by a group of radical filmmakers with Oakland Public Library collectives in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles. California Newsreel 510-238-6932 produced three documentary films on the Black Panther Party, Off the Pig (1968), [email protected] MayDay (1969), and Repression. The digitized films include outtakes and b-roll footage of: • MayDay rally – May 1, 1969 protest against police aggression and to free Huey P. Newton. Includes speeches by BPP members Bobby Seale and Kathleen Cleaver, Vietnam War activist and co-founder of the Youth International Party Stew Albert, Black newspaper publisher and politician, Carlton Goodlett, and Newton’s lawyer, Charles Gary. • Conference for a United Front Against Fascism – The Black Panthers' first national conference on anti-fascism held from July 18 to 21, 1969 at the Oakland Auditorium and DeFremery Park. -

{PDF EPUB} WHO the HELL IS STEW ALBERT by Stewart Edward Albert Stew Albert - Stew Albert

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} WHO THE HELL IS STEW ALBERT by Stewart Edward Albert Stew Albert - Stew Albert. Stewart Edward "Stew" Albert (4. december 1939 - 30. januar 2006) var et tidligt medlem af Yippierne , en anti-Vietnamkrigspolitisk aktivist og en vigtig skikkelse i New Left- bevægelsen i 1960'erne. Født i Sheepshead Bay- sektionen i Brooklyn , New York, til en medarbejder i New York City , havde han et relativt konventionelt politisk liv i sin ungdom, skønt han var blandt dem, der protesterede mod henrettelsen af Caryl Chessman . Han dimitterede fra Pace University , hvor han studerede politik og filosofi og arbejdede et stykke tid for City of New York velfærdsafdeling. I 1965 forlod han New York til San Francisco , hvor han mødte digteren Allen Ginsberg i City Lights Bookstore . Inden for få dage var han frivillig i Vietnam Day Committee i Berkeley, Californien . Det var der, han mødte Jerry Rubin og Abbie Hoffman , med hvem han medstifter Youth International Party eller Yippies. Han mødte også Bobby Seale og andre Black Panther Party- medlemmer der og blev en politisk aktivist på fuld tid. Rubin sagde engang, at Albert var en bedre underviser end de fleste professorer. Blandt de mange aktiviteter, han deltog i med Yippierne, var at smide penge fra balkonen på New York Stock Exchange , Pentagon's eksorsisme og præsidentkampagnen fra 1968 af en gris ved navn Pigasus . Han blev arresteret ved forstyrrelserne uden for Den Demokratiske Nationale Konvention i 1968 og blev udnævnt som en uindikeret medsammensvorne i Chicago Seven- sagen. Hans kone, Judy Gumbo Albert, hævdede ifølge hans New York Times nekrolog, at dette var fordi han arbejdede som korrespondent for Berkeley Barb . -

Shawyer Dissertation May 2008 Final Version

Copyright by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 Committee: Jill Dolan, Supervisor Paul Bonin-Rodriguez Charlotte Canning Janet Davis Stacy Wolf Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2008 Acknowledgements There are many people I want to thank for their assistance throughout the process of this dissertation project. First, I would like to acknowledge the generous support and helpful advice of my committee members. My supervisor, Dr. Jill Dolan, was present in every stage of the process with thought-provoking questions, incredible patience, and unfailing encouragement. During my years at the University of Texas at Austin Dr. Charlotte Canning has continually provided exceptional mentorship and modeled a high standard of scholarly rigor and pedagogical generosity. Dr. Janet Davis and Dr. Stacy Wolf guided me through my earliest explorations of the Yippies and pushed me to consider the complex historical and theoretical intersections of my performance scholarship. I am grateful for the warm collegiality and insightful questions of Dr. Paul Bonin-Rodriguez. My committee’s wise guidance has pushed me to be a better scholar. -

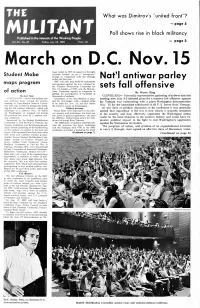

March on D.C. Nov. 15

TH£ What was Dimitrov's "united front"? - page 5 MILITANT Poll shows nse 1n black militancy Published in the interests of the Working People Vol. 33- No. 29 Friday, July 18, 1969 Price 15c - page 3 March on D.C. Nov. 15 cago called by SO in support of the eight Student Mobe activists fr a med up on a "consp ir a t~ y" ch arge in connect ion with the Chicago Nat'l antiwar parley police rio t last year . SMC will a lso help build the nationwide maps progra m mo r atorium against the war, planned by the Vietn am Moratoriu m Co mmittee for sets fall offensive Oct. 15; leaders of SMC a nd the Mor a to of action rium Committee a greed to cooperate in By Harry Ring getting the participati on of hundreds of By Joel Aber tho usands of students. CLEVELAND- A broadly representative gathering of antiwar activists CLEVELAND-About 500 student a nti Escalation of the fa ll offensive is plan meeting here July 4-5 initiated plans for a massive fall offensive against war activists from around the country ned for ovember, with a student strik e the Vietnam war culminating with a giant Washington demonstration meeting at Case-Western Reserve niver to be built for ov. 14, one day before sity here July 6 voted to plunge into build the massive march on Washing ton. Nov. 15 for the immediate withdrawal of all U.S. forces from Vietnam. ing the fall antiwar offensive, which will Politica l diversity In two days of political discussion at the conference it was generally culminate in a massive ov. -

All Power to the People: the Black Panther Party As the Vanguard of the Oppressed

ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE: THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AS THE VANGUARD OF THE OPPRESSED by Matthew Berman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Wilkes Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences with a Concentration in American Studies Wilkes Honors College of Florida Atlantic University Jupiter, Florida May 2008 ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE: THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AS THE VANGUARD OF THE OPPRESSED by Matthew Berman This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor, Dr. Christopher Strain, and has been approved by the members of her/his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Honors College and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ____________________________ Dr. Christopher Strain ____________________________ Dr. Laura Barrett ______________________________ Dean, Wilkes Honors College ____________ Date ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Author would like to thank (in no particular order) Andrew, Linda, Kathy, Barbara, and Ronald Berman, Mick and Julie Grossman, the 213rd, Graham and Megan Whitaker, Zach Burks, Shawn Beard, Jared Reilly, Ian “Easy” Depagnier, Dr. Strain, and Dr. Barrett for all of their support. I would also like to thank Bobby Seale, Fred Hampton, Huey Newton, and others for their inspiration. Thanks are also due to all those who gave of themselves in the struggle for showing us the way. “Never doubt that a small group of people can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” – Margaret Mead iii ABSTRACT Author: Matthew Berman Title: All Power to the People: The Black Panther Party as the Vanguard of the Oppressed Institution: Wilkes Honors College at Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. -

INTERVIEWS with KWAME TUR£ (Stoldy Carmichael) and Chokwe Luwumba Table of Contents

. BLACK LIBERATION 1968 - 1988 INTERVIEWS wiTh KWAME TUR£ (SToldy CARMichAEl) ANd ChokwE LuwuMbA Table of Contents 1 Editorial: THE UPRISING 3 WHAT HAPPENS TO A DREAM DEFERRED? 7 NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE-The Black Liberation Movement 1968-1988 Interview with Chokwe Lumumba, Chairman, New Afrikan People's Organization Interview with Kwame Ture", All-African People's Revolutionary Party 17 FREE THE SHARPEVILLE SIX ™"~~~~~~~ 26 Lesbian Mothers: ROZZIE AND HARRIET RAISE A FAMILY —— 33 REVISING THE SIXTIES Review of Todd Gitlin's The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage 38 BEHIND THE U.S. ECONOMIC DECLINE by Julio Rosado, Movimiento de Liberaci6n Nacional Puertorriquefio 46 CAN'T KILL THE SPIRIT ~ Political Prisoners & POWs Update 50 WRITE THROUGH THE WALLS Breakthrough, the political journal of Prairie Fire Organizing Committee, is published by the John Brown Book Club, PO Box 14422, San Francisco, CA 94114. This is Volume XXII, No. 1, whole number 16. Press date: June 21,1988. Editorial Collective: Camomile Bortman Jimmy Emerman Judy Gerber Judith Mirkinson Margaret Power Robert Roth Cover photo: Day of Outrage, December 1987, New York. Credit: Donna Binder/Impact Visuals We encourage our readers to write us with comments and criticisms. You can contact Prairie Fire Oganizing Committee by writing: San Francisco: PO Box 14422, San Francisco, CA 94114 Chicago: Box 253,2520 N. Lincoln, Chicago, IL 60614 Subscriptions are available from the SF address. $6/4 issues, regular; $15/yr, institutions. Back issues and bulk orders are also available. Make checks payable to John Brown Book Club. John Brown Book Club is a project of the Capp St. -

Sex and the Radical Imagination in the Berkeley Barb and the San Francisco Oracle Sinead Mceneaney

Radical Americas Special issue: Radical Periodicals Article Sex and the radical imagination in the Berkeley Barb and the San Francisco Oracle Sinead McEneaney St Mary’s University, Twickenham; [email protected] How to Cite: McEneaney, S. ‘Sex and the radical imagination in the Berkeley Barb and the San Francisco Oracle.’ Radical Americas 3, 1 (2018): 16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.ra.2018.v3.1.016. Submission date: 28 September 2017; Acceptance date: 20 December 2017; Publication date: 29 November 2018 Peer review: This article has been peer reviewed through the journal’s standard double blind peer-review, where both the reviewers and authors are anonymised during review. Copyright: c 2018, Sinead McEneaney. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited • DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.ra.2018.v3.1.016. Open access: Radical Americas is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Abstract This paper looks specifically at two influential newspapers of the American underground press during the 1960s. Using the Berkeley Barb and the San Francisco Oracle, the paper proposes two arguments: first, that the inability of the countercultural press to envisage real alternatives to sexuality and sex roles stifled any wider attempt within the countercultural movement to address concerns around gender relations; and second, the limitation of the ‘radical’ imagination invites us to question the extent to which these papers can be considered radical or countercultural. -

The Festival of Life: •Ÿchicago 1968•Ž Through the Lens of Post

Counterculture Studies Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 12 2019 The esF tival of Life: ‘Chicago 1968’ Through the Lens of Post-Truth Julie Stephens Victoria University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ccs Recommended Citation Stephens, Julie, The eF stival of Life: ‘Chicago 1968’ Through the Lens of Post-Truth, Counterculture Studies, 2(1), 2019, 20-29. doi:10.14453/ccs.v2.i1.12 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The esF tival of Life: ‘Chicago 1968’ Through the Lens of Post-Truth Abstract In the film HyperNormalisation by British documentary maker Adam Curtis, there is a section on Vladimir Putin’s purported puppet master, Vladislav Surkov who has also become known as ‘Putin’s Rasputin’. His central role in keeping Putin in power in Russia is documented by Curtis through collages of archival BBC footage and newsreels, and some scenes shot for the film. It is accompanied by Curtis’ bold and highly distinctive commentary. Surkov’s background in avant-gardetheatre is highlighted and portrayed as reaching right into the heart Russian politics by turning politics into a strange theatre where nobody knows what is true and what is fake any longer. Reality can be manipulated and shaped into anything you want it to be. Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This journal article is available in Counterculture Studies: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ccs/vol2/iss1/12 The Festival of Life: ‘Chicago 1968’ Through the Lens of Post-Truth Julie Stephens Victoria University of Technology In the film HyperNormalisation1 by British documentary maker Adam Curtis, there is a section on Vladimir Putin’s purported puppet master, Vladislav Surkov who has also become known as ‘Putin’s Rasputin’. -

From Guerrilla Theater to Media Warfare Abbie Hoffman's Riotous Revolution in America: a Myth Bruce Eric France, Jr

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2004 From guerrilla theater to media warfare Abbie Hoffman's riotous revolution in America: a myth Bruce Eric France, Jr. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation France, Jr., Bruce Eric, "From guerrilla theater to media warfare Abbie Hoffman's riotous revolution in America: a myth" (2004). LSU Master's Theses. 2898. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2898 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM GUERRILLA THEATER TO MEDIA WARFARE ABBIE HOFFMAN’S RIOTOUS REVOLUTION IN AMERICA: A MYTH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Communication Studies by Bruce Eric France, Jr. B.A., Louisiana State University, 1999 May 2004 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………...iii Introduction……………...………………………………...………………………………………1 Diggers/Early Agit-prop Performances/ Guerrilla Tactics and the Media……….………………………………….………….……….….14 The Exorcism of the Pentagon..………….……………………………………………….……...30 The Battle of Chicago and the Trial of the Chicago 8……………………………………...………………………………...42 Conclusion…………………………………………...…………………………………………..69 Works Cited……………………………………………………………...……………….……...87 Vita…………………………………………………...…………………………………………..90 ii Abstract The following thesis is a discussion of the radical activist Abbie Hoffman’s theatrical work to revolutionize the United States. -

Dope, Color TV, and Violent Revolution!

Scenarios ( ~e Revolution . by Jerry Rub~n Introduction by Eldridge Cleaver Designed by Q . Yi uent~n Fiore PPed bYJ: ZapPed b llll Retherford S:. :J.' NalZe 27Jz JI I(itr. ~ .on a7zr;t S, "8 alZ ch ,t 2t8"e,. To Nancy, Dope, Color TV, and Violent Revolution! JERRY RUBIN is the leader of 850 million Yippies. In a previous life Jerry was a sports reporter and a straight college student. He dropped out, visited Cuba and moved to Berkeley where he became known as the P. T. Barnum of the revolution, organizing spectacular events such as marathon Vietnam Day marches, teach-ins, International Days of Protest. Jerry lived for three years near the University of California working as an Outside Agitator to destroy the university. He ran for Mayor of Berkeley and came within one heart attack of winning in a four-man race. Jerry moved to New York in October 1967 and became Project Director of the March on the Pentagon. He appeared before "witch-hunt" committees of Congress dressed as an American Revolutionary War soldier, a bare-chested, armed guerrilla and Santa Claus. With Abbie Hoffman, Jerry created the Yippies as a fusion between the hippies and the New Left, and helped mJ>f>ilize the demonstrations during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in August 1968. The U.S. Government indicted Jerry and seven other revolutionaries for conspiracy to destroy the Democratic Convention, resulting in "The Conspiracy," perhaps the most important political trial in the history of the country. Jerry wants to hear your reactions to this book. -

June 19, 1975 / 301 *

June 19, 1975 / 301 * PEACE & FREEDOM THRU! NONVIOLENT ACTION I The Vietn araizatipn of Durham, North Carolina Chicago Poet-Activist, Joffre Stewart The Housing Plight of Eastern Inclians and, Stew Albert Watches Abbie Hoffman on Ty Feudalism was successful enough in its ürook, and I suspect it might be about family in the same issue of WIN, "Be: not then there is still hope fdr Jane Alpert. Paul Krassner day that by and by the¡e were mo¡e and life and family relations¡ But I don't know is counter-productive and In the meantime all othe¡s would be wise to sides,ieparatism -- more people, and the question inevitably keep coERrzEL tread lightly for, if she has prostituted her all the answers, either. Let's looking, iî¡'ie.;'-'--'-"' -vlcrbR arose as to Who gets to eat the o.nítÌulí? and, RAPER " GEORGE GOERTZEL prinçiples and other peoples' live's to save sliall we? -MARTHA JARRELL -MILDRED gets to hunt in the forestT (if a¡y Va. Palo Alto, Calif. her own, sho will do it again' ryho Oakton, forest is left). I know that this is not Ms. Deming's , ' . You guessed it. It riras the man or family just Deming's "To Fear Jane rationalization of the mattei but then I I read Barbara ' with the biggest, stronlest fortressh<ii.rse ,dj,oung, black man, Robert Cline is slated Ms' Deming she is a lot bigger person than I am. Aioert is To Fear Ourselves." suspect for living in and for refuge of his outlying for lhe Gas Chambe¡s in Rhode Island uh- out a point that is well taken' There The "peoples" movement is in no danger as The 5122175 issue was excellent from front ùrtugfrt clients, whose crops he natuially took a bíg less some poor folks start speaking up. -

I on 8/31/60 on 8/11/60

i -; UNiTED STATES GOVERNMENT DlflEC1'OR, Fill DATE! 8/31/60 SAC', l'iEW YORK (105-42122) I~ STElIAR&'EERT IS - R (OO:liY) Michigan of on 8/31/60 JaM•• Madison High School, , NY, made available a recc>rd University ~'hi. record "HI.ct. that S'I'E')f,RT 12/4/39 at Hanhettan, lITO, attended the above highLibrary, school fl'om 9/54 to 6/57. at "hich time h. I'l'adunted. His residence i. listeu as 2148 B. 29th Street, Brooklyn, NY, and his parents are MROLD alld HOSE hLB}J1T .. A copy of his school record has been furnished to Pace College, St. Johnls UniversityCollections School of Co~erce, the Bank of .America and Lehman Brothel's., all in l~YC. Credit, crimin01 Specialond BIN, ~!YC, are negative re subject , &rid his. rQn11~y. ifY indicesin are negative also. , l , ' On 8/11/60, -;;x.inin~d the records of the B02X'o. original of Brooklyn a.nd oeterl'll1u(;d thatfrom HAHOLD ROSE ALB2:riT ' 8: perJll8:nent ,; regis tration to vote in 19.57. This record reflects that EIAROill ~L!;JjRT >Ias bOl'Il..-9/2/02. is a US citizen and is .,"played in tho i,.City Hecords iJectlon,Copied {;ityof NY, Hunicipal Eld,3., j YC. !t_qt.~_" --.:..ALB1:.:H'l\f sage 1s not recorded but sbe was born in the US IlIH1 is . O· housewife-. lJ:'he ALB.EH'l's indicated that they resided at 2148 E. 29th Street~ Brooklyn, HY tor 17 years prior to this regls t;rGtio.'1.