My Travels Down Two Abbie Roads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weather Underground Rises from the Ashes: They're Baack!

Weather Underground Rises from the Ashes: They're Baack! I attended part of a January 20, 2006, "day workshop of interventions" — aka "a day of dialogic interventions" — at Columbia University on "Radical Politics and the Ethics of Life."[1] The event aimed "to stage a series of encounters . to bring to light . the political aporias [sic] erected by the praxis of urban guerrilla groups" in Europe and the United States from the 1960s to the 80s.[2] Hosted by Columbia's Anthropology Department, workshop speakers included veterans and leaders of the Weather Underground Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers, historian Jeremy Varon, poststructuralist theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and a dozen others. The panel I sat through was just awful.[3] Veterans of Weather (as well as some fans) seem to be on a drive to rehabilitate, cleanse, and perhaps revive it — not necessarily as a new organization, but rather as an ideological component of present and future movements. There have been signs of such a sanitization and romanticization for some time. A landmark in this rehabilitation is Bill Ayers, Fugitive Days: A Memoir (Beacon Press 2001; Penguin Books 2003). This is a dubious account, full of anachronisms, inaccuracies, unacknowledged borrowings from unnamed sources (such as the documentary, Atomic Cafe, 17-19), adding up to an attempt to cover over the fact that Ayers was there only for a part of the things he describes in a volume that nonetheless presents itself as a memoir. It's also faux literary and soft core ("warm and wet and welcoming"(68)), "ruby mouth"(38), "she felt warm and moist"(81)), full of archaic sexism, littered with boasts of Ayers's sexual achievements, utterly untouched by feminism. -

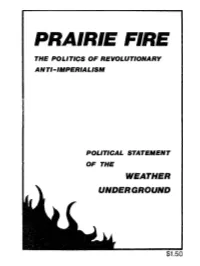

The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism

FIRE THE POLITICS OF REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-IMPERIALISM ---- - ... POLITICAL STATEMENT OF THE UND£ $1.50 Prairie Fire Distributing Lo,rnrrntte:e This edition ofPrairie Fire is published and copyrighted by Communications Co. in response to a written request from the authors of the contents. 'rVe have attempted to produce a readable pocket size book at a re'ls(m,tbl.e cost. Weare printing as many as fast as limited resources allow. We hope that people interested in Revolutionary ideas and events will morc and better editions possible in the future. (And that this edition at least some extent the request made by its authors.) PO Box 411 Communications Co. Times Plaza Sta. PO Box 40614, Sta. C Brooklyn, New York San FrancisQ:O, Ca. 11217 94110 Quantity rates upon request to Peoples' Bookstores and Community organiza- tlOBS. PRAIRIE FIRE THE POLITICS OF REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-IMPERIALISM POLITICAL STATEMENT , OF THE WEATHER Copyright © 1974 by Communications Co. UNDERGROUND All rights reserved The pUblisher's copyright is not intended to discourage the use ofmaterial from this book for political debate and study. It is intended to prevent false and distorted reproduction and profiteering. Aside from those limits, people are free to utilize the material. This edition is a copy of the original which was Printed Underground In the US For The People Published by Communications Co. 1974 +h(~ of OlJr(1)mYl\Q~S tJ,o ~Q.Ve., ~·Ir tllJ€~ it) #i s\-~~\~ 'Yt)l1(ch ~, \~ 10 ~~\ d~~~ee.' l1~rJ 1I'bw~· reU'w) ~it· e\rrp- f'0nit'l)o yralt· ~YZlpmu>I')' ca~-\e.v"C2lmp· ~~ ~[\.ll10' ~li~ ~n. -

News From: Oakland Public Library for IMMEDIATE RELEASE

News from: Oakland Public Library FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 4, 2019 AAMLO Digitizes Black Panther Party Films All digitized films can be viewed online Web: http://oaklandlibrary.org/news/2019/04/aamlo-digitizes-black-panther- party-films Oakland, CA – In April 2018, the African American Museum & Library at Oakland was awarded a Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) Recordings at Risk grant to digitize and provide access online to 98 films documenting the Black Panther Party (BPP) and student and union protest movements of the late 1960s and 1970s from the Henry J. Williams Jr. Film Collection. Those films are now available online in AAMLO’s Internet Archive page or in the finding aid for the Henry J. Williams Jr. Film Collection in the Online Archive of Media Contacts: California. Matt Berson The films include footage shot by the documentary film collective Newsreel, an Public Information Officer organization founded in New York City by a group of radical filmmakers with Oakland Public Library collectives in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles. California Newsreel 510-238-6932 produced three documentary films on the Black Panther Party, Off the Pig (1968), [email protected] MayDay (1969), and Repression. The digitized films include outtakes and b-roll footage of: • MayDay rally – May 1, 1969 protest against police aggression and to free Huey P. Newton. Includes speeches by BPP members Bobby Seale and Kathleen Cleaver, Vietnam War activist and co-founder of the Youth International Party Stew Albert, Black newspaper publisher and politician, Carlton Goodlett, and Newton’s lawyer, Charles Gary. • Conference for a United Front Against Fascism – The Black Panthers' first national conference on anti-fascism held from July 18 to 21, 1969 at the Oakland Auditorium and DeFremery Park. -

Bernardine Dohrn

Bernardine Dorhn: Never the Good Girl, Not Then, not Now: An Interview By Jonah Raskin Who doesn’t have a reaction to the name and the reputation of Bernadine Dohrn? Is there anyone over the age of 60 who doesn’t remember her role at the outrageous Days of Rage demonstrations, her picture on FBI “wanted posters,” or her dramatic surrender to law enforcement officials in Chicago after a decade as a fugitive? To former members of SDS, anti-war activists, Yippies, Black Panthers, White Panthers, women’s liberationists, along with students and scholars of Weatherman and the Weather Underground, she probably needs no introduction. Sam Green featured her in his award-winning 2002 film, The Weather Underground. Todd Gitlin added to her iconic stature in his benchmark cultural history, The Sixties, though he was never on her side of the ideological splits or she on his. Dozens of books about the long decade of defiance have documented and mythologized Dohrn’s role as an American radical. Of course, her flamboyant husband and long-time partner, Bill Ayers, has been at her side for decades, aiding and abetting her much of the time, and adding to her legendary renown and notoriety. Born in 1942, and a diligent student at the University of Chicago, she attended law school there and in the late 1960s “stepped out of the role of the good girl," as she once put it. She has never really stepped back into it again, though she’s been a wife, a mother, and a professional woman for more years than she was a street fighting woman. -

Monthly Review Press Catalog, 2011

PAID PAID Social Structure RIPON, WI and Forms of NON-PROFIT U.S. POSTAGE U.S. POSTAGE Consciousness ORGANIZATION ORGANIZATION PERMIT NO. 100 volume ii The Dialectic of Structure and History István Mészáros Class Dismissed WHY WE CANNOT TEACH OR LEARN OUR WAY OUT OF INEQUALITY John Marsh JOSÉ CARLOS MARIÁTEGUI an anthology MONTHLY REVIEW PRESS Harry E. Vanden and Marc Becker editors and translators the story of the center for constitutional rights How Venezuela and Cuba are Changing the World’s Conception of Health Care the people’s RevolutionaRy lawyer DOCTORS 2011 Albert Ruben Steve Brouwer WHAT EVERY ENVIRONMENTALIST NEEDS TO KNOW ABOUT CAPITALISM JOHN BELLAMY FOSTER FRED MAGDOFF monthly review press review monthly #6W 29th Street, 146 West NY 10001 New York, www.monthlyreview.org 2011 MRP catalog:TMOI.qxd 1/4/2011 3:49 PM Page 1 THE DEVIL’S MILK A Social History of Rubber JOHN TULLY From the early stages of primitivehistory accu- mulation“ to the heights of the industrial revolution and beyond, rubber is one of a handful of commodities that has played a crucial role in shaping the modern world, and yet, as John Tully shows in this remarkable book, laboring people around the globe have every reason to THE DEVIL’S MILK regard it as “the devil’s milk.” All the A S O C I A L H I S T O R Y O F R U B B E R advancements made possible by rubber have occurred against a backdrop of seemingly endless exploitation, con- quest, slavery, and war. -

Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 12-2013 "Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957 Kayla D. Meyers College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Meyers, Kayla D., ""Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 767. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/767 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull”: Deconstructing The Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies from The College of William and Mary by Kayla Danielle Meyers Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Charles McGovern, Director ________________________________________ Arthur Knight ________________________________________ Marc Raphael Williamsburg, VA December 3, 2013 Table of Contents Introduction: The Poet is Holy.........................................................................................................2 -

{PDF EPUB} WHO the HELL IS STEW ALBERT by Stewart Edward Albert Stew Albert - Stew Albert

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} WHO THE HELL IS STEW ALBERT by Stewart Edward Albert Stew Albert - Stew Albert. Stewart Edward "Stew" Albert (4. december 1939 - 30. januar 2006) var et tidligt medlem af Yippierne , en anti-Vietnamkrigspolitisk aktivist og en vigtig skikkelse i New Left- bevægelsen i 1960'erne. Født i Sheepshead Bay- sektionen i Brooklyn , New York, til en medarbejder i New York City , havde han et relativt konventionelt politisk liv i sin ungdom, skønt han var blandt dem, der protesterede mod henrettelsen af Caryl Chessman . Han dimitterede fra Pace University , hvor han studerede politik og filosofi og arbejdede et stykke tid for City of New York velfærdsafdeling. I 1965 forlod han New York til San Francisco , hvor han mødte digteren Allen Ginsberg i City Lights Bookstore . Inden for få dage var han frivillig i Vietnam Day Committee i Berkeley, Californien . Det var der, han mødte Jerry Rubin og Abbie Hoffman , med hvem han medstifter Youth International Party eller Yippies. Han mødte også Bobby Seale og andre Black Panther Party- medlemmer der og blev en politisk aktivist på fuld tid. Rubin sagde engang, at Albert var en bedre underviser end de fleste professorer. Blandt de mange aktiviteter, han deltog i med Yippierne, var at smide penge fra balkonen på New York Stock Exchange , Pentagon's eksorsisme og præsidentkampagnen fra 1968 af en gris ved navn Pigasus . Han blev arresteret ved forstyrrelserne uden for Den Demokratiske Nationale Konvention i 1968 og blev udnævnt som en uindikeret medsammensvorne i Chicago Seven- sagen. Hans kone, Judy Gumbo Albert, hævdede ifølge hans New York Times nekrolog, at dette var fordi han arbejdede som korrespondent for Berkeley Barb . -

Diane Di Prima

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU ENGL 6350 – Beat Exhibit Student Exhibits 5-5-2016 Diane Di Prima McKenzie Livingston Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/beat_exhibit Recommended Citation Livingston, McKenzie, "Diane Di Prima" (2016). ENGL 6350 – Beat Exhibit. 2. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/beat_exhibit/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Exhibits at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ENGL 6350 – Beat Exhibit by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Livingston 1 Diane DiPrima’s Search for a Familiar Truth The image of Diane DiPrima∗ sitting on her bed in a New York flat, eyes cast down, is emblematic of the Beat movement. DiPrima sought to characterize her gender without any constraints or stereotypes, which was no simple task during the 1950s and 1960s. Many of the other Beats, who were predominately male, wrote and practiced varying degrees of misogyny, while DiPrima resisted with her characteristic biting wit. In the early days of her writing (beginning when she was only thirteen), she wrote about political, social, and environmental issues, aligning herself with Timothy Leary’s LSD Experiment in 1966 and later with the Black Panthers. But in the latter half of her life, she shifted focus and mostly wrote of her family and the politics contained therein. Her intention was to find stable ground within her familial community, for in her youth and during the height of the Beat movement, she found greater permanence in the many characters, men and women, who waltzed in and out of her many flats. -

Shawyer Dissertation May 2008 Final Version

Copyright by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 Committee: Jill Dolan, Supervisor Paul Bonin-Rodriguez Charlotte Canning Janet Davis Stacy Wolf Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2008 Acknowledgements There are many people I want to thank for their assistance throughout the process of this dissertation project. First, I would like to acknowledge the generous support and helpful advice of my committee members. My supervisor, Dr. Jill Dolan, was present in every stage of the process with thought-provoking questions, incredible patience, and unfailing encouragement. During my years at the University of Texas at Austin Dr. Charlotte Canning has continually provided exceptional mentorship and modeled a high standard of scholarly rigor and pedagogical generosity. Dr. Janet Davis and Dr. Stacy Wolf guided me through my earliest explorations of the Yippies and pushed me to consider the complex historical and theoretical intersections of my performance scholarship. I am grateful for the warm collegiality and insightful questions of Dr. Paul Bonin-Rodriguez. My committee’s wise guidance has pushed me to be a better scholar. -

2008 OAH Annual Meeting • New York 1

Welcome ear colleagues in history, welcome to the one-hundred-fi rst annual meeting of the Organiza- tion of American Historians in New York. Last year we met in our founding site of Minneap- Dolis-St. Paul, before that in the national capital of Washington, DC. On the present occasion wew meet in the world’s media capital, but in a very special way: this is a bridge-and-tunnel aff air, not limitedli to just the island of Manhattan. Bridges and tunnels connect the island to the larger metropolitan region. For a long time, the peoplep in Manhattan looked down on people from New Jersey and the “outer boroughs”— Brooklyn, theth Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island—who came to the island via those bridges and tunnels. Bridge- and-tunnela people were supposed to lack the sophistication and style of Manhattan people. Bridge- and-tunnela people also did the work: hard work, essential work, beautifully creative work. You will sees this work in sessions and tours extending beyond midtown Manhattan. Be sure not to miss, for example,e “From Mambo to Hip-Hop: Th e South Bronx Latin Music Tour” and the bus tour to my own Photo by Steve Miller Steve by Photo cityc of Newark, New Jersey. Not that this meeting is bridge-and-tunnel only. Th anks to the excellent, hard working program committee, chaired by Debo- rah Gray White, and the local arrangements committee, chaired by Mark Naison and Irma Watkins-Owens, you can chose from an abundance of off erings in and on historic Manhattan: in Harlem, the Cooper Union, Chinatown, the Center for Jewish History, the Brooklyn Historical Society, the New-York Historical Society, the American Folk Art Museum, and many other sites of great interest. -

West Coast Rock Final Version

WEST COAST ROCK AND THE COUNTERCULTURE MOVEMENT Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Magistra der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Christina DREIER am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr.phil. Hugo Keiper Graz, 2012 An dieser Stelle möchte ich mich bei meinem Betreuer Prof. Dr. Hugo Keiper für seine Unterstützung auf meinem Weg von der Idee bis zur Fertigstellung der Arbeit herzlich bedanken. Seine Ideen, Anregungen und Hinweise, sowie sein umfangreiches musikalisches, kulturelles und literarisches Wissen waren mir eine große Hilfe. Des Weiteren gilt mein Dank meinem Onkel Patrick, der die Arbeit Korrektur gelesen und mir dadurch sehr geholfen hat. Natürlich möchte ich mich auch von ganzem Herzen bei all jenen bedanken, die mich während meiner gesamten Studienzeit tatkräftig unterstützt haben. Danke Mama, Papa, Oma, Opa, Lisa, Eva, Markus, Gabi, Erwin UND DANKE JÜRGEN! . Table of Contents 0. Timeline ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Socio-Historical Background ....................................................................................................................... 4 2.1. Political Issues ............................................................................................................................... -

Interview with Anita Hoffman

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Browse All Oral History Interviews Oral History Program 11-28-1992 Interview with Anita Hoffman Anita Hoffman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/oralhistoryprogram Part of the Oral History Commons Recommended Citation Sixties Radicals, Then and Now: Candid Conversations with Those Who Shaped the Era © 2008 [1995] Ron Chepesiuk by permission of McFarland & Company, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640. www.mcfarlandpub.com. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Oral History Program at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse All Oral History Interviews by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOUISE PETTUS ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Interview #236 HOFFMAN, Anita HOFFMAN, Anita Anti-war activist, feminist, poverty awareness activist, scholar Interviewed: November 28, 1992 Interviewer: Ron Chepesiuk Index by: Alyssa Jones Length: 1 hour, 50 minutes, 7 seconds Abstract: In her November 1992 interview with Ron Chepesiuk, Anita Hoffman detailed her experiences in the 1960s and her time with her ex-husband, Abbie Hoffman. Hoffman, aside from speaking about her ex-husband, covered such topics as poverty, racism, the Weathermen (Weather Underground), the Black Panthers and the Black Power movement, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Women’s Liberation, and the Youth International Party. Hoffman also discussed sexism, mental illness, in reference to Abbie and her studies as a Psychology major, the Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill hearings, and the technology revolution. This interview was conducted for inclusion into the Louise Pettus Archives and Special Collections Oral History Program.