A POLITICAL HISTORY of PARTHIA Oi.Uchicago.Edu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

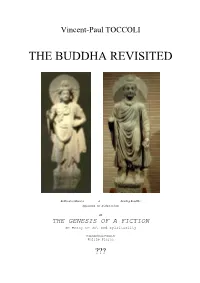

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

What the Romans Knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 • Part II

What the Romans knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know • Part II 1 What the Romans knew Archaic Roma Capitolium Forum 2 (Museo della Civiltà Romana, Roma) What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Wars against Carthage resulted in conquest of the Phoenician and Greek civilizations – Greek pantheon (Zeus=Jupiter, Juno = Hera, Minerva = Athena, Mars= Ares, Mercury = Hermes, Hercules = Heracles, Venus = Aphrodite,…) – Greek city plan (agora/forum, temples, theater, stadium/circus) – Beginning of Roman literature: the translation and adaptation of Greek epic and dramatic poetry (240 BC) – Beginning of Roman philosophy: adoption of Greek schools of philosophy (155 BC) – Roman sculpture: Greek sculpture 3 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Greeks: knowing over doing – Romans: doing over knowing (never translated Aristotle in Latin) – “The day will come when posterity will be amazed that we remained ignorant of things that will to them seem so plain” (Seneca, 1st c AD) – Impoverished mythology – Indifference to metaphysics – Pragmatic/social religion (expressing devotion to the state) 4 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Western civilization = the combined effect of Greece's construction of a new culture and Rome's destruction of all other cultures. 5 What the Romans Knew • The Mediterranean Sea (Mare Nostrum) – Rome was mainly a sea power, an Etruscan legacy – Battle of Actium (31 BC) created the “mare nostrum”, a peaceful, safe sea for trade and communication – Disappearance of piracy – Sea routes were used by merchants, soldiers, -

Social Memory in the Eclogues of Virgil and Calpurnius Siculus

“Now I have forgotten all my verses”: Social Memory in the Eclogues of Virgil and Calpurnius Siculus Paul Hulsenboom Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen Abstract This paper examines the use of social memory in the pastoral poetry of Virgil and Cal- purnius Siculus. A comparison of the references to Rome’s social memory in both these works points to a development of this phenomenon in Latin bucolic poetry. Whereas Vir- gil’s Eclogues express a genuine anxiety with the preservation of Rome’s ancient customs and traditions in times of political turbulence, Calpurnius Siculus’s poems address issues of a different kind with the use of references to social memory. Virgil’s shepherds see their pastoral community disseminating: they start forgetting their lays or misremem- bering verses, indicating the author’s concern with Rome’s social memory and, thereby, with the prosperity and stability of the Res Publica. Calpurnius Siculus, on the other hand, has his herdsmen strive for the emperor’s patronage and a literary career in the big city, bored as they are by the countryside. They desire a larger, more cohesive and active urban community in which they and their songs will receive the acclaim they deserve and consequently live on in Rome’s social memory. Calpurnius Siculus’s poems are, however, in contrast to Virgil’s, no longer concerned with social memory in itself. Keywords: social memory, Eclogues, Virgil, Calpurnius Siculus 14 Paul Hulsenboom Abstrakt Niniejszy artykuł omawia rolę pamięci zbiorowej w poezji idyllicznej Wergiliusza i Kalpurniusza Sykulusa. Rezultaty porównania między odwołaniem się obu autorów do rzymskiej pamięci zbiorowej wskazują na rozwój tego tematu w łacińskiej poezji bu- kolicznej. -

After Cultures Meet

Chapter 2 After Cultures Meet Abstract No culture is isolated from other cultures. Nor is any culture changeless, invariant or static. All cultures are in a state of constant flux, driven by both internal and external forces. All of these are the inherent dynamics of the multiculturally based world per se. In this chapter, beginning with the question ‘why Mesopotamia had the oldest civilization in the world’, the spatial interaction of ancient civilizations is assessed; and four non-linear patterns of intercultural dynamics are presented. Our empirical analyses of the four major ancient civilizations (the Mesopotamian, the Egyptian, the Indus, and the Chinese) focus on intercultural influences as well as how they have shaped the spatial dynamics of the world as a whole. Keywords Ancient civilization Á Adjacency Á Intercultural dynamics Á Mesopotamia Á Spatial interaction 2.1 Focus on Mesopotamia In Chap. 1, we have discussed the natural and geographical factors contributing to the birth of ancient civilizations. Some empirical evidence has also explained to some extent why existing cultures and culture areas are conflicting and comple- mentary. Till now, many issues relating to the origin of and evolution of ancient civilizations are still puzzling both anthropologists and human geographers. They include such questions as: Why Mesopotamia has the oldest civilization in the world? Why is the Chinese civilization younger than the other three ancient civilizations (i.e., ancient Egyptian, the ancient Indus and the Mesopotamian)? Why have some ancient civilizations eventually become extinct while others not? What are the driving forces for the human civilizations to grow, to expand and to decline eventually? Before dealing with these issues, let us first look at the spatial mechanism of cultural formation in Mesopotamia. -

Title Page Echoes of the Salpinx: the Trumpet in Ancient Greek Culture

Title Page Echoes of the salpinx: the trumpet in ancient Greek culture. Carolyn Susan Bowyer. Royal Holloway, University of London. MPhil. 1 Declaration of Authorship I Carolyn Susan Bowyer hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 2 Echoes of the salpinx : the trumpet in ancient Greek culture. Abstract The trumpet from the 5th century BC in ancient Greece, the salpinx, has been largely ignored in modern scholarship. My thesis begins with the origins and physical characteristics of the Greek trumpet, comparing trumpets from other ancient cultures. I then analyse the sounds made by the trumpet, and the emotions caused by these sounds, noting the growing sophistication of the language used by Greek authors. In particular, I highlight its distinctively Greek association with the human voice. I discuss the range of signals and instructions given by the trumpet on the battlefield, demonstrating a developing technical vocabulary in Greek historiography. In my final chapter, I examine the role of the trumpet in peacetime, playing its part in athletic competitions, sacrifice, ceremonies, entertainment and ritual. The thesis re-assesses and illustrates the significant and varied roles played by the trumpet in Greek culture. 3 Echoes of the salpinx : the trumpet in ancient Greek culture Title page page 1 Declaration of Authorship page 2 Abstract page 3 Table of Contents pages -

Questions for History of Ancient Rome by Garret Fagan

www.YoYoBrain.com - Accelerators for Memory and Learning Questions for History of Ancient Rome by Garret Fagan Category: Pre-Republic - (12 questions) What is the range of mountains that run Apennine range down the center of Italy 3 main plains in Italy Po River Valley in northplain of Latium around RomeCampania around Naples How many legendary kings of Rome were 7 there Who was first legendary king of Rome Romulus What was second king of Rome, Numa establishing religious traditions of Rome Pompilius, famous for What was Rome 3rd legendary king, Tullius attacking neighboring peoples Hostilus, famous for Where were the 2 Tarquin kings from Etruscan What was basic political unit pre-Republic tribes - started as 3 and expanded to 21 Romans born into What social unit were pre-Republic families clans grouped into What was the function of the Curiate to ratify the senate's choice of king and Assembly in pre-Republican Rome confer power of command (imperium) on him Who was the last king of Rome Tarquinius Superbus (the Arragont) Who was the woman raped by Sextus Lucretia Tarquinius leading to ouster of king Category: Republican - (30 questions) What was the title of the second in command Master of Horse to a temporary dictator in Republican Rome What was the Struggle of the Orders in internal social and political conflict between Roman history Plebians and Patrician classes that ran between 494 BC and 287 BC When did the Roman plebians first "secede" 494 B.C. from Rome during Struggle of the Orders When was law passed making laws passed 287 -

Date and Time Terms and Definitions

Date and Time Terms and Definitions Date and Time Terms and Definitions Brooks Harris Version 35 2016-05-17 Introduction Many documents describing terms and definitions, sometimes referred to as “vocabulary” or “dictionary”, address the topics of timekeeping. This document collects terms from many sources to help unify terminology and to provide a single reference document that can be cited by documents related to date and time. The basic timekeeping definitions are drawn from ISO 8601, its underlying IEC specifications, the BIPM Brochure (The International System of Units (SI)) and BIPM International vocabulary of metrology (VIM). Especially important are the rules and formulas regarding TAI, UTC, and “civil”, or “local”, time. The international standards that describe these fundamental time scales, the rules and procedures of their maintenance, and methods of application are scattered amongst many documents from several standards bodies using various lexicon. This dispersion makes it difficult to arrive at a clear understanding of the underlying principles and application to interoperable implementations. This document collects and consolidates definitions and descriptions from BIPM, IERS, and ITU-R to clarify implementation. There remain unresolved issues in the art and science of timekeeping, especially regarding “time zones” and the politically driven topic of “local time”. This document does not attempt to resolve those dilemmas but describes the terminology and the current state of the art (at the time of publication) to help guide -

The Dancing Floor of Ares Local Conflict and Regional Violence in Central Greece

The Dancing Floor of Ares Local Conflict and Regional Violence in Central Greece Edited by Fabienne Marchand and Hans Beck ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Supplemental Volume 1 (2020) ISSN 0835-3638 Edited by: Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Monica D’Agostini, Andrea Gatzke, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, Nadini Pandey, John Vanderspoel, Connor Whatley, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Assistant Editor: Charlotte Dunn Contents 1 Hans Beck and Fabienne Marchand, Preface 2 Chandra Giroux, Mythologizing Conflict: Memory and the Minyae 21 Laetitia Phialon, The End of a World: Local Conflict and Regional Violence in Mycenaean Boeotia? 46 Hans Beck, From Regional Rivalry to Federalism: Revisiting the Battle of Koroneia (447 BCE) 63 Salvatore Tufano, The Liberation of Thebes (379 BC) as a Theban Revolution. Three Case Studies in Theban Prosopography 86 Alex McAuley, Kai polemou kai eirenes: Military Magistrates at War and at Peace in Hellenistic Boiotia 109 Roy van Wijk, The centrality of Boiotia to Athenian defensive strategy 138 Elena Franchi, Genealogies and Violence. Central Greece in the Making 168 Fabienne Marchand, The Making of a Fetter of Greece: Chalcis in the Hellenistic Period 189 Marcel Piérart, La guerre ou la paix? Deux notes sur les relations entre les Confédérations achaienne et béotienne (224-180 a.C.) Preface The present collection of papers stems from two one-day workshops, the first at McGill University on November 9, 2017, followed by another at the Université de Fribourg on May 24, 2018. Both meetings were part of a wider international collaboration between two projects, the Parochial Polis directed by Hans Beck in Montreal and now at Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, and Fabienne Marchand’s Swiss National Science Foundation Old and New Powers: Boiotian International Relations from Philip II to Augustus. -

The Roman Empire: the Defender of Early First Century Christianity

Running head: THE ROMAN EMPIRE 1 The Roman Empire: the Defender of Early First Century Christianity John Toone A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2011 THE ROMAN EMPIRE 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ David A. Croteau, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Michael J. Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Willie E. Honeycutt, D.Min. Committee Member ______________________________ James H. Nutter, D.A. Honors Director ______________________________ Date THE ROMAN EMPIRE 3 Abstract All of the events, authors, and purposes of the books in the New Testament occurred under the reign of the Roman Empire (27 B.C.—A.D. 476). Therefore, an understanding of the Roman Empire is necessary for comprehending the historical context of the New Testament. In order to fully understand the impact of the Roman Empire on the New Testament, particularly before the destruction of the Jewish Temple in A.D. 70, Rome’s effect on religion (and the religious laws that governed its practice) must be examined. Contrary to expectations, the Roman Empire emerges from this examination as the protector (not persecutor) of early Christianity. Scripture from this time period reveals a peaceful relationship between the new faith and Roman authorities. THE ROMAN EMPIRE 4 The Roman Empire: The Defender of Early First Century Christianity Any attempt to describe the life of first century Christians before A.D. 70 is ultimately tenuous without understanding the cultural background of the society in which they lived. -

On the Roman Frontier1

Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Impact of Empire Roman Empire, c. 200 B.C.–A.D. 476 Edited by Olivier Hekster (Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Lukas de Blois Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt Elio Lo Cascio Michael Peachin John Rich Christian Witschel VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/imem Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Edited by Daniëlle Slootjes and Michael Peachin LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016036673 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1572-0500 isbn 978-90-04-32561-6 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-32675-0 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Joshua's Long Day Continued

Joshua's Long Day continued Joshua 10:13b "So the sun stood still in the midst of heaven, and hasted not to go down about a whole day". This is a record of fact, an eye witness account - not alleged, not a metaphor, not an allegory, and not pretext, not a myth set to poetry and not a command to the deities of the sun and moon. This was not a localized event. There is only one sun and one moon seen from the whole earth. Purple Sun, and Crimson and Ruby Sun There may be a search for evidence of sun miracles in the daily coral layers. True wisdom costs us our all. The price of wisdom is not money. It is our will and beyond ruby like suns. The price of ancient coral is about $100,000 a kilo. Job 28:18 "No mention shall be made of coral, or of pearls: for the price of wisdom is above rubies." Perhaps the sun appeared purple as a ruby as the Chinese recorded at the sun miracle in 141 BC when the sun may have been dimmed. "On the last day of the twelfth month (11 February 141 BC) it thundered. The sun appeared purple. Five planets moved in retrograde and guarded the constellation T'ai-wei. The moon passed through the center of the constellation T'ien-t'ing." The Grand Scribes Records, Volume II, p.213. The moon was in the polar region of the sky. The sun must move 180° from Scorpius to Taurus. Thus, the sun would appear nearer the pole star and in the polar region.